|

by Danielle Alexander

December 30, 2020

from

ClassicalWisdom Website

Italian version

Hydra photographed

above

the scenic lake of Llyn y Fan Fach

in the

Brecon Beacons Dark Sky Reserve

in

Wales, U.K.

Image:

Huw James Media

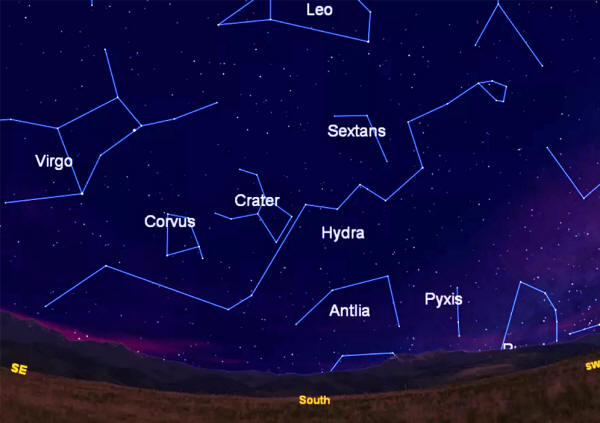

In modern astronomy, this constellation is often divided into two or

four parts.

One is a female water

snake called Hydra, the other, Hydrus.

A smaller

constellation located in the southern hemisphere, Hydrus is

considered the male counterpart of this giant, sprawling star

serpent.

At twenty-seven stars,

this is the largest constellation in the sky, visible from almost

anywhere around the world.

Unfortunately, it lacks

particularly bright stars, so can be difficult to spot. The

brightest, an orange star named Alphard, meaning solitary

in Arabic, is so named due to its seeming loneliness in the abyss.

The six stars that form the snake's head are the constellation's

most distinctive feature. The head has a culmination on January 31st,

whereas the tail culmination occurs during April.

Culmination is when the

constellation, or in this instance part of the constellation,

reaches the zenith of the celestial sphere's rotation, appearing

higher in the sky.

Greek

Astronomy

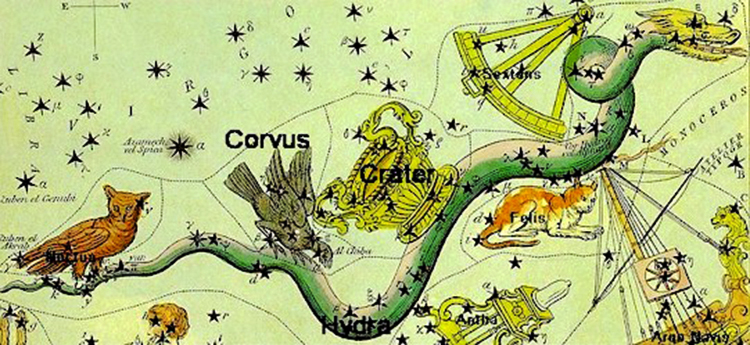

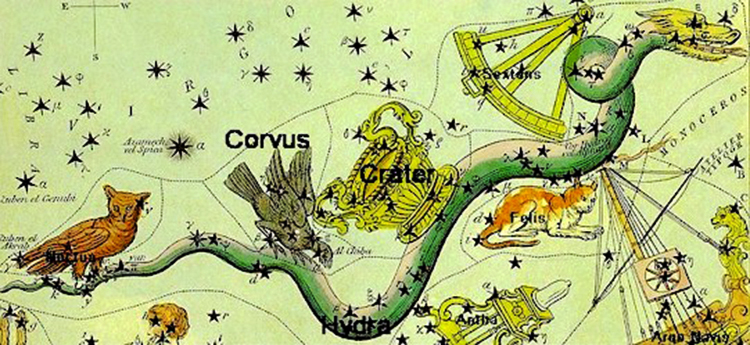

An artistic impression of Hydra

with

its surrounding asterisms.

Image:

Sidney Hall

In case you haven't noticed, humans have a curious fascination with

the night sky.

Some of the stories we

"see" as constellations go all the way back to Mesopotamian times

(1300-1000 BC), where sky-watching was a prestigious occupation.

Gradually, early astronomy developed a mythic component.

Over time, different

narratives evolved in response to changes in interests and values

over the generations, reflected in patterns in the sky. These

narratives likely experienced dramatic development during the

transition from oral to written transmission, but to what is extent

is unknown.

Today, the International Astronomical Union lists 88 official

constellations, many of which date back to Ptolemy's seminal

work on astronomy,

The Almagest (A.D 150).

Compared to the rest of the ancient world, the Greeks began

investigating the stars rather late (Hesiod and Homer,

500 BC). As such, they incorporated a lot of astronomy from their

eastern neighbors.

The Greek astral mythos

canon was solidified by Eratosthenes, in a work now lost to

us.

Slithering

Across the Sky

Hydra was identified as far back as

ancient Sumer, where it was named

after the primordial salt-water dragon goddess, Tiamat.

In the myth, Tiamat

slaughters the inhabitants of Earth, her offspring with Abzu/Apsu,

the primordial god of fresh water, after they had slain her

beloved.

As myth and time

progressed, she was usurped by the storm god

Marduk, who overthrew the queen

to gain divine regency amongst the Mesopotamian pantheons.

The introduction of Marduck, Babylon's supreme deity, reflected the

increase of political power that Babylon had over the Sumerian and

Akkadian states of Mesopotamia.

In this way, the

Mesopotamian myth of the serpent contains a simplified,

mythologized history of the region.

The serpent also held importance in Egypt, where it was likened to

the unfurling, curling nature of the Nile, signifying changes in

zodiacal alignments and celestial events.

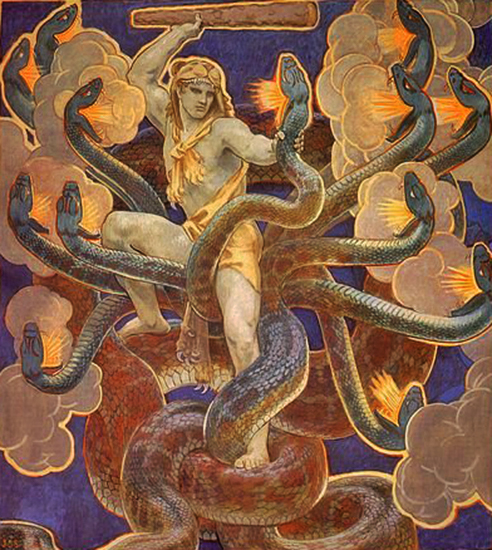

However, in ancient Greece, this constellation was the formidable

Lernean Hydra, the second of

the great Labors of Heracles.

The story goes that

Hercules was set against the Hydra, mythological monster with nine

heads that oozed venomous substances from gaping jaws.

The offspring of Typhon and Echidne, reared by Hera, the Hydra was

terrorizing the sacred and fertile region of Lerna, near Argos. On

ancient Greek coins, the Hydra is stylized with seven heads to mimic

the river Amymone, where it was said to have lived prior to invading

the Lernean swamp.

The problem of the

multiple heads couldn't be resolved by decapitation due to their

fierce regrowth, sprouting two or three more heads from their bloody

stumps.

Heracles, with the aid of Athena, tempted the Hydra out of hiding

with flaming arrows and held his breath when it emerged.

He then lopped off its

heads, but they just grew back. The twisting tail sought to trip him

as it gripped his ankles and he uselessly waved his club around.

Hera, determined to see

the young hero fail, sent a crab to pinch his feet. It was swiftly

squished.

This then became the

astrological constellation of Cancer.

Hercules and the Hydra

The flailing and ever-increasing number of heads was becoming

overwhelming for Heracles, who was saved by his charioteer, Iolaus.

Iolaus heroically set fire to the

grove in which the battle occurred and waved burning branches at the

fresh stumps, cauterizing the wounds and preventing their regrowth.

This also provided

sufficient distraction for Heracles, who was able to access the

golden head of the Hydra and remove it with a golden falchion (a

type of sword), thus claiming victory over his second trial.

He then dipped his arrows

into the disemboweled body of the monster. However, his victory was

short-lived as Eurystheus, who had set the trial, held that

Hercules had cheated because he received assistance.

Lerna was known as the location where Dionysus had ventured to

the Underworld, and so housed several divine shrines to the god,

where secret nocturnal rites were performed.

Additionally, the

Mysteries of Demeter were celebrated there, in a shrine set at

the locale where Hades took Persephone to the Underworld.

It appears this location

was a hotspot for traversing realms.

Robert Graves (The

Greek Myths) has suggested that this classical mythology

was a historical attempt to suppress the archaic fertility rituals

of the Mysteries that took place there.

Crimes of

Corvus

Urania's Mirror, 1825

Hydra actually has two constellations perched on its back:

This peculiar combination

is associated with Apollo's punishment of the Crow.

The tale goes that the

bird was sent by Apollo to retrieve water for a ritual libation.

Unfortunately, some figs distracted his feathered friend while on

the quest.

The Crow waited several

days for the figs to ripen in order to pluck the delicious snack

from the tree and gobble them up, having forgotten his heaven-sent

task.

Once his tummy was full, the Crow suddenly remembered - the water

for the gods!

In a bid to save his own

feathers, he snatched a water-snake and brought it before Apollo,

claiming it had consumed all the spring water. Apollo, seeing the

ruse, cursed the Crow to suffer from thirst during the season of fig

ripening.

In order that the crime

would not be forgotten, Apollo put the imagery into the heavens,

with neither the Snake nor the Crow able to reach the bowl of water.

In some versions, the Crow returns with a bowl of water, albeit

several days late, and the Snake was only placed amongst the stars

to deter the Crow from the bowl.

This is not the only

story involving Apollo cursing the Crow, and it makes you wonder why

he kept them in employment!

The 'Bowl'

Constellation in Troy

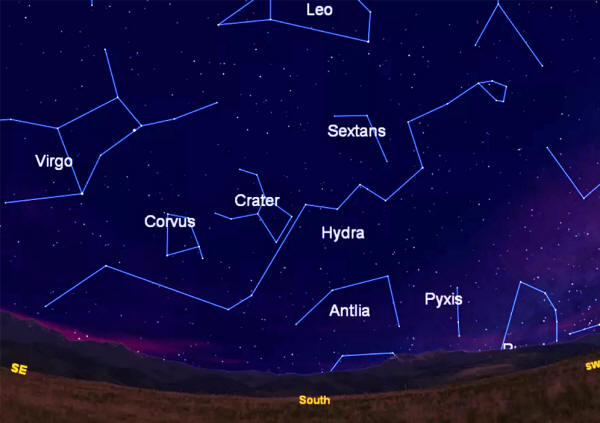

Image showing Hydra in the southern sky

at

around 9 pm ET, mid-latitudes, Northern Hemisphere.

Credit:

© Starry Night Software

The Bowl, also known as the Crater, is a constellation

in its own right and has mythological roots going back to Troy.

While the city was

ruled by Demophon, it was plagued with a... well, plague.

Demophon,

distraught by the epidemic, invoked Apollo, who had worked with

Poseidon to construct Troy and so favored the city.

In order to stop the

plague, Apollo demanded a maiden of noble origin be sacrificed

to the patron god of the cities every year.

Demophon devised a system in which all the noble women would be

sacrificed except his own daughters.

This worked for a

while, until another noble family patriarch, Mastousios,

refused to enter his daughter.

The king, outraged,

ordered that his daughter be sacrificed, without drawing lots.

Mastousios played the long game and did not seek immediate

retribution against the king. He pretended to befriend him, and

spent a year winning his favor.

When it came to the

sacrifice, he informed the king he had chosen a victim this year

and organized the ceremony. The king, no doubt busy with royal

affairs of state, sent his daughters ahead of him with a wave

and a "I'll meet you there."

The vengeful noble Mastousious slaughtered the king's daughters

and mixed their blood into the wine that he presented to the

King upon his arrival.

Unsurprisingly, the

plan came to a bad end when the King realized what had happened

and threw Mastousious into the sea.

This body of water

retained the name, and the event was placed into the sky as a

reminder against abusing power for one's own benefit.

This tale does not bare much resemblance to the imagery presented in

the stars. It appears to have been created to provide an origin for

the harbor and sea name in the region, rather than being

representative of the story around the constellation.

Conclusion

The serpent in the stars reflects the tales of love,

betrayal, and political upheaval.

The size of this

constellation reflects the variations of mythos surrounding it,

regardless of whether it is seen entirely as Hydra or divided into

the crow and the crater.

As the story of the bowl

constellation in Troy demonstrates, some Greek tales almost seem

forced into place.

The serpentine motif is

predominantly associated with the pre-Olympian pantheons and the

rage of

primordial Tiamat, yet it continues

to dominate today by taking up the largest part of the night sky.

References

-

Cornelius, G.

(2005) - The complete guide to the constellations - London:

Duncan Baird.

-

Ératosthène,

Hygin, Aratus and Hard, R. (2015) - Constellation myths -

Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.110-114

-

Fontenrose, J.

(1940) - Apollo and the Sun-God in Ovid - The American

Journal of Philology, 61(4), 429-444. doi:10.2307/291381

-

Graves, R. (2012)

-

The Greek Myths - New York:

Penguin Books.

-

Kirk, G. S.

(1972) - Greek Mythology: Some New Perspectives - The

Journal of Hellenic Studies, 92, pp.74-85

-

Liritzis, I.,

Bousoulegka, E., Nyquist, A., Castro, B., Alotaibi, F., &

Drivaliari, A. (2017) - New evidence from archaeoastronomy

on Apollo oracles and Apollo-Asclepius related cult -

Journal Of Cultural Heritage, 26, 129-143. doi:

10.1016/j.culher.2017.02.011

-

Schaefer, B.

(2006) - The Origin of the Greek Constellations - Scientific

American, 295(5), pp.96-101.

|