|

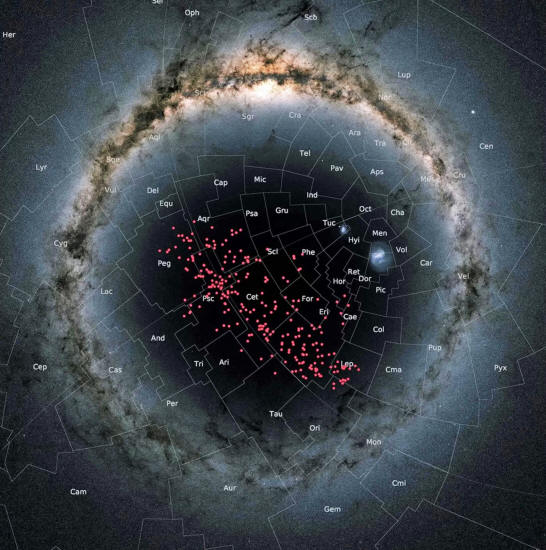

the Milky Way curves around the entire image in an arc, with the newly discovered river of stars displayed in red

and

covering almost the entire

southern Galactic hemisphere.

Since then, that cluster has whipped four long circles around the edge of the Milky Way. In that time, the Milky Way's gravity has stretched that cluster out from a blob into a long stellar stream.

Right now, the stars are

passing relatively 'close' to Earth, just about 330 light-years

away. And scientists say that river of stars could help

determine the mass of the entire Milky Way.

The 'river', which is 1,300 light-years long and 160 light-years wide, winds through the Milky Way's vast, dense star field.

But 3D-mapping data from Gaia, a European Space Agency spacecraft, showed that the stars in the stream moved together at roughly the same speed and in the same direction.

Though space is full of these stellar streams, they're often difficult to study because they're well-camouflaged amidst surrounding stars.

Typically, these stellar streams are also much farther away.

Scientists suspect that star clusters, like the one that eventually became this stellar stream can reveal how galaxies get their stars.

But in a big, heavy

galaxy like the Milky Way, those clusters usually end up shredded,

with gravity pulling individual stars in different directions. This stream is big enough though, and heavy enough, that it remained intact (albeit stretched) in the billion years it has circled the galactic center.

And there may be more

stars in the stream than those found in the initial Gaia data...

|