|

by Andrew Moseman

December 01, 2010

from

DiscoverMagazine Website

A study by Yale astronomer Pieter van Dokkum just took the estimated number of stars in the

universe - 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (1022), or 100 sextillion - and

tripled it.

And you thought nothing good ever happens on Wednesdays...

Van Dokkum's

study in the journal Nature (A

Substantial Population of Low-Mass Stars in Luminous Elliptical

Galaxies) focuses on

red dwarfs, a class of small, cool

stars.

They're so small and cool, in fact, that up to now

astronomers haven't been able to spot them in galaxies outside our

own.

That's a serious holdup when you're trying to account for all

the stars there are.

As a consequence, when estimating how

much of a galaxy's mass stars account for - important to

understanding a galaxy's life history - astronomers basically had to

assume that the relative abundance of red-dwarf stars found in the

Milky Way held true throughout the universe for every galaxy type

and at every epoch of the universe's evolution, Dr. van Dokkum says.

"We always knew that was sort of a stretch, but it was the only

thing we had. Until you see evidence to the contrary you kind of go

with that assumption," he says.

Christian

Science Monitor

But van Dokkum's team, using the Keck

Observatory in Hawaii, surveyed eight elliptical

galaxies nearby (between about 50 and 300 million light years

away) for these dim stars.

Their spectrometer could catch the

collective signature of these faraway red dwarfs and estimate how

many of them the neighbor galaxies harbor.

In the Milky Way there

are about 100 red dwarfs for every one star like the sun, but in

these galaxies that number may be more like 1,000 to one.

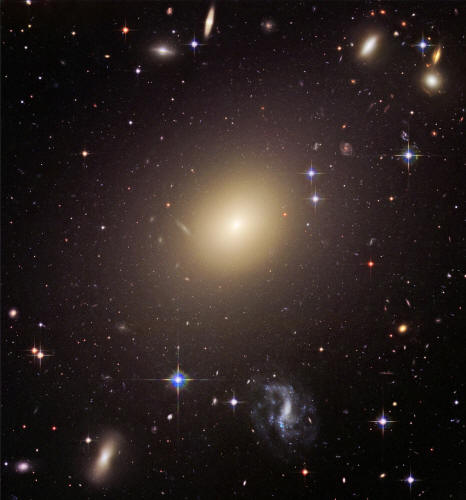

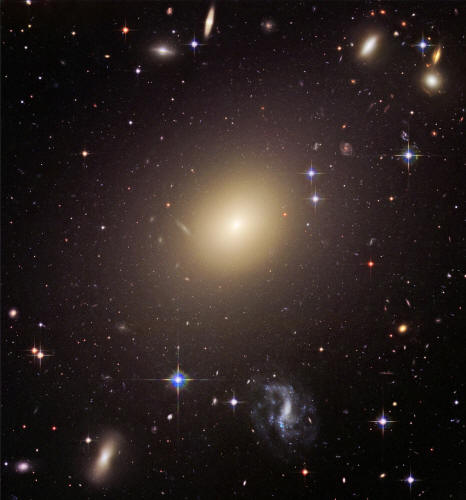

Elliptical galaxies are some of the

largest galaxies in the universe. The largest of these galaxies were

thought to hold more than 1 trillion stars (compared with the 400

billion stars in our Milky Way).

The new finding suggests there may

be five to 10 times as many stars inside

elliptical galaxies than previously thought, which would triple

the total number of known stars in the universe, researchers said.

Space.com

While van Dokkum's Nature paper

was released to the public today, it's been raising a more private

ruckus already:

For the past month, astronomers have

been buzzing about van Dokkum's findings, and many aren't too happy

about it, said astronomer Richard Ellis of the California Institute

of Technology.

Van Dokkum's paper challenges the assumption of,

"a

more orderly universe" and gives credence to "the idea that the

universe is more complicated than we think," Ellis said.

"It's a

little alarmist."

Ellis said it is too early to tell if van Dokkum

is right or wrong, but it is shaking up the field "like a cat among

pigeons."

Van Dokkum agreed, saying,

"Frankly, it's a big pain."

AP

And besides tripling the number of stars

in the universe (isn't that enough???) and infuriating some

astronomers, van Dokkum's find has some serious secondary

implications.

More stars, of course, means the opportunity for

more

planets, and many recently found

exoplanets orbit red dwarfs.

That

includes,

Furthermore, the plethora of red dwarfs

could explain a

dark matter mystery:

Elliptical galaxies posed a problem: The

motions of the stars they contained implied that they had more mass

than one would get by adding the mass of the normal matter

astronomers observed to the expected amount of dark matter in the

neighborhood.

Some suggested that ellipticals somehow had extra dark

matter associated with them. Instead, the newly detected red dwarfs

could account for the difference, van Dokkum says.

Christian

Science Monitor

|