|

by Ben Chu

as described in Revelation 21:21 from the manuscript The Apocalypse of Margaret of York, c1475.

Photo by

Alamy are shocked that nations are once again isolating from the world.

The real surprise would be if they didn't...

Isolationism isn't new and is fuelled by deep human desires...

Donald Trump has declared the

'economic independence' of the United States and seems to be trying

to excise the US from the global trading system his country has so

painstakingly built since the Second World War - a system that has

delivered considerable economic benefits for nations across the

planet.

China's president Xi Jinping has, for many years, been advocating zili gengsheng for China, which translates as 'self-reliance'.

In pursuit of this, Beijing has been discouraging

imports and trying to enhance Chinese domestic production of

everything from food to computer chips.

...boasted Vladimir Putin last year, dismissing the impact of the avalanche of Western trade sanctions that swept over the country in 2022 and sought to turn it into an economic pariah.

The Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has adopted a slogan of atmanirbhar bharat, or 'self-reliant India', for what is now the most populous nation in the world.

Even the traditionally outward-facing European

Union has begun exploring how the bloc can achieve greater economic

autonomy in areas ranging from energy to defense.

Yet, though it might feel like a very modern

departure, this impulse to face inward, and for nations to cast off

the shackles of interconnection and dependence, is not new. In fact,

it's ancient.

Indeed, understanding how the two interact and

reinforce each other might be crucial to understanding the enduring

appeal of this way of thinking - and for getting a sense of where it

can lead us, whether as individuals, as nation states or as a global

community.

When Alexander the Great paid Diogenes a visit, the conqueror of worlds asked the ragged ascetic, who was enjoying a siesta at the time,

The answer, so the story goes, was that Diogenes asked him to:

of a philosopher in a barrel speaking to a king on horseback,

surrounded by

advisers and trees. from the manuscript Les diz moraulx des philosophes, c1418-20. Courtesy the Houghton Library,

Harvard

University

But there's no doubting the power of the story

and the idea it encapsulated. The tale of Diogenes' extreme

indifference to the most powerful ruler in the ancient world has

been in circulation for almost 2,000 years as perhaps the supreme

example of the desire for self-sufficiency.

But, from those earliest days of Western civilization, the moral virtue of autarky was not just a goal for an individual, but an aspiration for the collective too.

According to Aristotle, a contemporary of

Diogenes, the ideal city state in the ancient world was also

self-sufficient, and those inside the polity would have everything

they needed to pursue a good philosophical life - unlike those

outside it.

led to the view that to be more self-sufficient

was to be closer to God...

'The term self-sufficient,' as Aristotle put it,

This Aristotelian connection between individual

and collective self-sufficiency - the personal and the political -

endured into the Christian era.

But the dumb ox did more than perhaps any other

to build the philosophical underpinnings of the Catholic faith.

That was the seminal 'scholastic' argument of the

medieval age. And it led to the view that to be more self-sufficient

was to be closer to God.

He noted that there are two ways a city can feed itself:

Aquinas also proffered a moral case for autarky when he noted that,

Thus, in the medieval Christian world, the

pursuit of autarky - on both a personal and a community level

- was sanctified, widening its appeal, and finding a clear

manifestation in the monasteries, largely self-sufficient

communities independent of external authority, except the Church

and God, and producing their own food, wine and

clothing.

Western Christian missionaries were banned and those that were already in the country were persecuted. Emigration was forbidden and foreign trade was reduced almost to nothing.

Autarky was seen as a necessary

means to preserve traditional religion and morality in Japan, but

economic isolationism was also bound up with resistance to the

incursions of foreign empires and was a practical means of securing

sovereignty and control, not just an abstract principle.

commerce among rivalrous European states

had served to corrupt

relations...

From what he imagined was an anthropological

perspective, Rousseau conjectured in his Discourse on Inequality

(1754) that primitive man had been naturally 'solitary', coming

together with others only for mating, and was much happier for it.

There are clear echoes of the freedom of Diogenes here in Rousseau's vision of a 'state of nature'. And, importantly, this had implications for his own beliefs about how humans ought to live.

Rousseau, like Aquinas before him, made the leap from extolling the general moral virtuousness of self-sufficiency to recommending it as a trade policy for nation states.

Rousseau inspired one of the paragons of German idealist philosophy, Johann Gottlieb Fichte.

In his work The Closed Commercial State

(1800), Fichte sought to fuse Rousseau's proto-anthropological

perspective with the ideas of Immanuel Kant, who had envisioned a

model of 'perpetual peace' among nations.

But for Fichte, on the contrary, commerce among rivalrous European states had served to corrupt relations, and economic life had to be disentangled for peace to have a chance.

Charles Fourier, the son of a cloth merchant from Besançon, took the autarkic ideas of Fichte and Rousseau in a beguiling new direction.

Contemporary portraits show an austere-looking individual, with a thin mouth with sharply down-turned corners.

Yet Fourier's rather prim exterior belied one of

the most eccentric of the utopian socialists of the early 19th

century, with his speculations that the world's seas would one day

turn into lemonade and that humans would evolve tails.

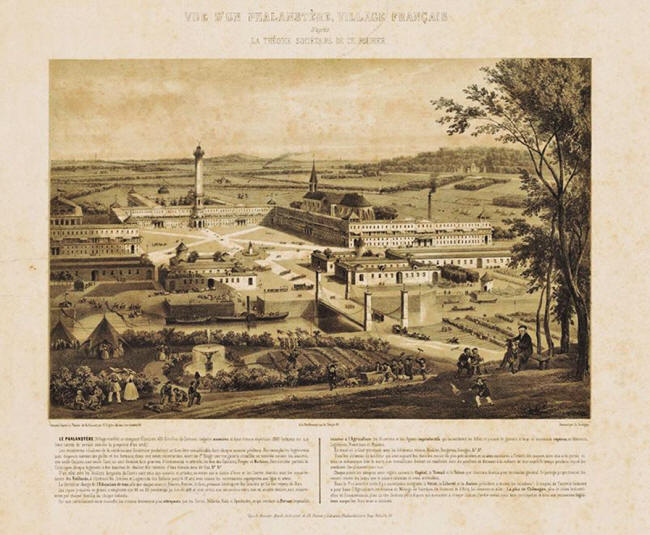

He outlined a 'unitary education' for all children in the phalanx, regardless of family wealth, and a 'social minimum', which was effectively a guaranteed minimum annual income. The influence of the phalanstery on 1960s hippie commune living is evident.

The kibbutzim of Israel also echoed many elements of his ideas.

featuring buildings surrounding a courtyard,

a central

column, and people in a rural landscape. H. Fugèr and Charles-François Daubigny circa the 19th century. Courtesy the Houghton Library, Harvard Wikipedia

This was partly because he believed that one of the problems with globalization was that it encouraged 'voracious consumerism'.

Again, the link between the personal and the

social when it comes to autarky rises to the surface.

an India independent of British rule was for a network of

'tiny gardens of Eden'...

In this view, autarky becomes the natural path to both domestic and international social justice - an appealing goal for those committed to equity and sustainability.

For those same reasons, it has also appealed to

those seeking to build a new world, free from European imperial

rule.

This is why the image of the spinning wheel once

sat at the heart of the tricolor Indian flag.

Yet at other times Gandhi struck a much more isolationist tone, insisting that 'it is certainly our right and duty to discard everything foreign that is superfluous and even everything foreign that is necessary if we can produce or manufacture it in our country.'

How to reconcile such statements?

Gandhi's self-sufficiency movement - swadeshi in Hindi - has to be understood as self-sufficiency for India primarily in relation to Britain, the imperial overlord.

The movement was announced in 1905 in Bengal alongside a boycott of British goods.

Swadeshi was Gandhi's antidote to what he

saw as the predatory imperial capitalism of the British. And that

mindset of India needing self-sufficiency remained long after

independence was achieved.

For him, autarky and his distinctive

vision of African socialism were

inseparable.

Born in Idaho in 1911, LeFevre began his career as a self-proclaimed 'fly-by-night' door-to-door salesman, and later promoted a New Age cult in the 1930s.

But it was only in the 1960s that he found his true calling as a popularized of libertarian economic ideas.

At his 'Freedom School' in Colorado, LeFevre

developed the theory of 'autarchism' in an attempt to clarify his

philosophy and distinguish his radical anti-government beliefs from

'anarchism'.

This was essentially a strain of libertarianism

reaching back to the ancient Greek ideal of individual

self-sufficiency, rather than the political and economic conception.

toward economic self-sufficiency have not typically emerged

from grassroots efforts...

His school was an implacable opponent of any kind of government intervention or economic redistribution. The future billionaire chemicals and fossil fuels industrial magnate Charles Koch was one of the students of LeFevre's school in the 1960s and was profoundly influenced by the experience.

Koch went on to pour huge amounts of his family's

money into libertarian think tanks, arguing for major tax cuts,

drastic reductions in government welfare spending and radical

deregulation.

The New Hampshire Free State project, established in 2001, is trying to create a libertarian community in the US, by encouraging like-minded folk to move, en masse, to the state of New Hampshire.

There are estimated to be between 10,000 and 30,000 communes, or 'intentional communities', around the world, including,

Adolf Hitler's autarkism was a response to Germany's experience in the First World War, when the country had been starved by the British navy's blockade.

Writing in the 1920s, Hitler dismissed the idea that Germany could nourish its population through increases in agricultural productivity and lamented that,

The road to national self-preservation for the former lance-corporal would have to run through a radical program of building national self-sufficiency.

And he believed that Germany's salvation lay in

conquering and exploiting the rural bounty of lands to the east,

thus gaining the notorious Lebensraum ('living space').

Ironically, Hitler's nemesis, Joseph Stalin,

despite having those fecund lands under his direct control, also

felt a dread of national insecurity and decided to pursue a policy

of self-sufficiency for the Soviet Union in the 1930s, deliberately

cutting off exports and seeking to establish Soviet economic

independence from the 'capitalist world'.

were primarily motivated by the spectre of war,

rather than ideals of national

virtue...

But a personal moral dimension was present there too.

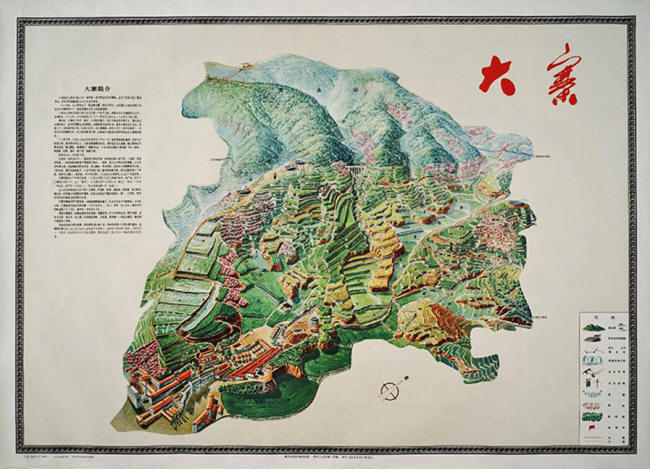

The farmers of the hitherto obscure village of Dazhai in Shanxi province were held up by Maoist propaganda as hardworking and self-reliant exemplars to be followed by the entire nation.

shows a detailed landscape with mountains, fields and buildings,

featuring

artistic 3D elements. agricultural region of Dazhai in Shanxi province, China, 1977. Courtesy the University of Victoria, Canada

In the 1950s, Kim Il Sung, the North Korean Communist leader and anti-Japanese guerrilla fighter, made national self-sufficiency not just an important objective, but the lodestar of his new regime.

And he called it juche.

Squint and it's possible to see a relationship

between that and the aspiration to personal independence embodied in

autarky in ancient Greece.

The outcomes of their visions for self-sufficiency were catastrophic, resulting in genocide and suffering on a scarcely imaginable scale.

Today, North Korea remains a hermit kingdom,

shaped by a totalitarian family cult, effectively a prison state for

its people, a warning of the economic and social toll of

isolationism.

The context was the threat of Great Britain, which had been cast out in the War of Independence but which was still a profound military danger to the nascent republic.

One of the first acts of the first Congress was

the imposition of a tariff.

Washington's first address to Congress with what Trump said

to the same institution...

Instead, List said that countries with great unrealized industrial potential that were trying to catch up with the productivity frontier leader - in this case, Britain - should act to protect their immature factories from competition with the leader with powerful import restrictions until they were strong enough to compete.

It remains a compelling argument today for

leaders of both developing and wealthy nations alike, often invoked

to justify trade protectionism as a cornerstone of industrialization

or re-industrialization strategies.

By explicitly linking trade policy to national

self-reliance and defense capabilities, Trump was resurrecting ideas

that were influential at the very birth of the US republic.

Mencius Moldbug, the blogging alias of the US computer scientist Curtis Yarvin, is a prominent tech-authoritarian theorist whose influence extends to some Trump-aligned politicians and wealthy backers.

Yarvin advocates dismantling US

democracy in favor of a

monarchy or a national 'CEO'-like figure.

This, he said, in an echo of Fichte, would enhance the prospects of peace between states.

And Yarvin drew on some historic Asian autarkic regimes for justification:

Yarvin's policy recommendation for 21st-century America?

The autarkic urge makes for some strange

bedfellows.

The obsidian is not from the area, suggesting that these Stone Age humans who lived some 320,000 years ago were trading with other groups.

Part of what defines our species - making us distinct from other apes - seems to be Homo sapiens' co-operative and social nature and, specifically, our capability for 'cultural learning'.

Rousseau was mistaken to believe that primitive

man was a self-sufficient loner.

There have, undoubtedly, been some communities who have been disrupted and suffered due to the impact of globalization, but there's no reason to believe, despite what some politicians argue, that a mass turn inwards by nations would undo that damage.

And such a retreat would likely cause severe harm

to the livelihoods of billions of others across the planet. Trade

and interconnection, whether or not we realize it or like it, is

part of who we are - and always has been.

What's most striking about autarky is its adaptability as a program and an ideology. It can appeal impressively across seemingly opposing political, social and ideological lines.

It's been adopted, at various times, by political movements on the Left and the Right, by believers and atheists, by nationalists and cosmopolitans, by fascists and communists, by rich states and poor states, by imperial powers and the colonized, by environmentalists and industrialists.

It can be justified by the objective of peace or the demands of war. Any unit - from the individual, to the household, to the village, to the city, to the nation - can apparently aspire to self-sufficiency.

It can be borne of a backward-looking nostalgia - a desire to turn the clock back or preserve the status quo - or of a belief that it's a progressive and necessary program to build the future.

Like a historical

El Niño weather pattern, the drive

for self-sufficiency keeps returning, unpredictably but, also,

seemingly inevitably.

But perhaps it's also that umbilical link in autarky - evident since the days of ancient Greece - between personal morality and the question of how we should relate to each other within communities and between communities.

To be successful, political movements have to appeal to something fundamental in everyone's nature.

Our innate sense of the virtue of

self-reliance is often the foundation stone on which they build.

|