|

from

ZeroHedge Website

It is no secret that as the Fed's centrally-planned New Normal has unfolded, one after another central-planner and virtually all economists, have been caught wrong-footed with their constant predictions of an "imminent" economic surge, any minute now, and always just around the corner.

And yet,

nearly

six years after Lehman, five years after the end of the last

"recession" (even as the depression for most rages on), America is about to

have its worst quarter in decades (excluding the great financial crisis),

with a -2% collapse in GDP, which has been blamed on... the weather.

In other words, a delta of hundreds of

billion in "growth lost or uncreated" due to, well..., snow in the

winter.

In his own words:

That's right - blame it on the lack of war!

Well, that's just unacceptable: surely

all the world needs for some serious growth is for war casualties to be in

the billions, not in the paltry hundreds of thousands.

To be sure, Cowen is quick covers his ass with some quick diplomacy.

After all how dare he implicitly suggest that the only reason the US escaped the Great Depression is what some say was its orchestrated entry into World War 2:

So what is it about war that makes economic "growth" that much greater. Apparently it has to do with an urgency in spending.

As in urgently spending more than the trillions of dollars needed to support the US welfare state now, and spending even more trillions in hopes of, you guessed it, stumbling on the next "Internet" (which apparently wasn't created by Al Gore).

What we find surprising is that it took the econofrauds this long to scapegoat that last falsifiable boundary - the lack of war - for the lack of growth.

But they are finally stirring:

The fun part will be when economists finally do get their suddenly much desired war (just as they did with World War II, and World War I before it, the catalyst for the creation of the Fed of course), just as they got their much demanded trillions in monetary stimulus.

Recall that according to Krugman the Fed has failed to stimulate the economy because it simply wasn't enough:

One needs moar!

Instead he frames it as an issue of trade offs:

And let's not forget that GDP is nothing but economic bullshit, confirmed when in recent weeks Europe - seemingly tired of waiting for war - arbitrarily decided to add the "benefits" of prostitution and narcotics.

And there you have all the meaningless growth you can dream of. If only on paper.

Because hundreds of million of people in the

developed world, without a job, out of the labor force, can only be placated

with dreams of "hope and change" for so long. And certainly not once they

get hungry, or realize that the biggest lie of all in the Bismarckian

welfare state - guaranteed welfare - is long broke. Cowen's conclusion:

That's great. Now all we need is some economist

and/or central-planner who actually gets top billing and determines policy

to have a different conclusion, and decide that 4% growth is actually worth

m(b)illions of dead people.

May Be Hurting Economic Growth

from

NYTimes Website

with a Sputnik 3 replica in 1959.

Credit Bettmann/Corbis

The claim is also distinct from the Keynesian argument that preparing for war lifts government spending and puts people to work.

Rather, the very possibility of war focuses the attention of governments on getting some basic decisions right - whether investing in science or simply liberalizing the economy.

Such focus ends up improving a nation's longer-run prospects.

Fundamental innovations such as nuclear power, the computer and the modern aircraft were all pushed along by an American government eager to defeat the Axis powers or, later, to win the Cold War.

The Internet was initially designed to help this country withstand a nuclear exchange, and Silicon Valley had its origins with military contracting, not today's entrepreneurial social media start-ups. The Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite spurred American interest in science and technology, to the benefit of later economic growth.

War brings an urgency that governments otherwise fail to summon.

For instance, the Manhattan Project took six years to produce a working atomic bomb, starting from virtually nothing, and at its peak consumed 0.4 percent of American economic output. It is hard to imagine a comparably speedy and decisive achievement these days.

As a teenager in the 1970s, I heard talk about the desirability of rebuilding the Tappan Zee Bridge. Now, a replacement is scheduled to open no earlier than 2017, at least - provided that concerns about an endangered sturgeon can be addressed.

Kennedy Airport remains dysfunctional, and La Guardia is hardly cutting edge, hobbling air transit in and out of New York. The $800 billion stimulus bill, in response to the recession, has not changed this basic situation.

Today the major slow-growing Western European nations have very little fear of being taken over militarily, and thus their politicians don't face extreme penalties for continuing stagnation. Instead, losing office often means a boost in income from speaking or consulting fees or a comfortable retirement in a pleasant vacation spot.

Japan, by comparison, is faced with territorial and geopolitical pressures from China, and in response it is attempting a national revitalization through the economic policies of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Ian Morris, a professor of classics and history at Stanford, has revived the hypothesis that war is a significant factor behind economic growth in his recent book, "War! What Is it Good For? Conflict and the Progress of Civilization From Primates to Robots."

Morris considers a wide variety of cases, including the Roman Empire, the European state during its Renaissance rise and the contemporary United States. In each case there is good evidence that the desire to prepare for war spurred technological invention and also brought a higher degree of internal social order.

Another new book, Kwasi Kwarteng's "War and Gold - A 500-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt," makes a similar argument but focuses on capital markets.

Mr. Kwarteng, a Conservative member of British Parliament, argues that the need to finance wars led governments to help develop monetary and financial institutions, enabling the rise of the West. He does worry, however, that today many governments are abusing these institutions and using them to take on too much debt. (Both Mr. Kwarteng and Mr. Morris are extending themes from Azar Gat's 820-page magnum opus, "War in Human Civilization," published in 2006.)

Yet another investigation of the hypothesis appears in a recent working paper (Unified China and Divided Europe) by the economists Chiu Yu Ko, Mark Koyama and Tuan-Hwee Sng.

The paper argues that Europe evolved as more politically fragmented than China because China's risk of conquest from its western flank led it toward political centralization for purposes of defense.

This centralization was useful at first but eventually held China back. The European countries invested more in technology and modernization, precisely because they were afraid of being taken over by their nearby rivals.

But here is the catch:

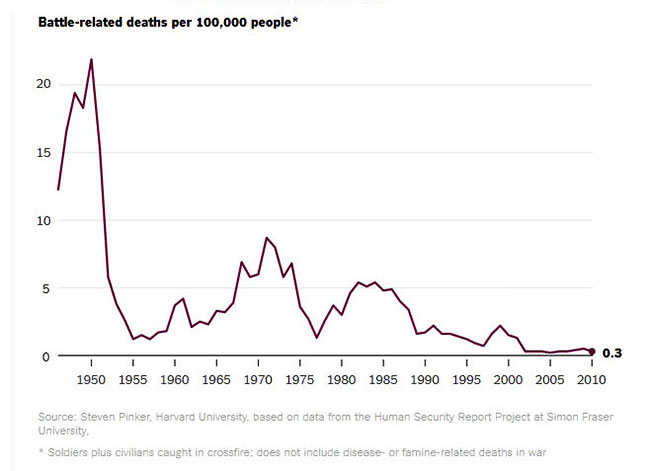

Technologies have become much more destructive, and so a large-scale war would be a bigger disaster than before. That makes many wars less likely, which is a good thing, but it also makes economic stagnation easier to countenance.

There is a more optimistic read to all this than may first appear. Arguably the contemporary world is trading some growth in material living standards for peace - a relative paucity of war deaths and injuries, even with a kind of associated laziness.

We can prefer higher rates of economic growth and progress, even while recognizing that recent G.D.P. figures do not adequately measure all of the gains we have been enjoying. In addition to more peace, we also have a cleaner environment (along most but not all dimensions), more leisure time and a higher degree of social tolerance for minorities and formerly persecuted groups.

Our more peaceful and - yes - more slacker-oriented world is in fact better than our economic measures acknowledge.

Living in a largely peaceful world with 2 percent G.D.P. growth has some big advantages that you don't get with 4 percent growth and many more war deaths. Economic stasis may not feel very impressive, but it's something our ancestors never quite managed to pull off.

The real questions are whether we can do any better, and whether the recent prevalence of peace is a mere temporary bubble just waiting to be burst.

|