by Prof Peter Dale Scott

April 9, 2010

from

GlobalResearch Website

|

Peter Dale Scott, a former Canadian diplomat and English Professor at the

University of California, Berkeley, is the author of Drugs Oil and War, The

Road to 9/11, and The War Conspiracy: JFK, 9/11, and the Deep Politics of

War.

His book, Fueling America's War Machine: Deep Politics and the CIA’s

Global Drug Connection is in press, due Fall 2010 from Rowman & Littlefield.

He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal. |

Alfred McCoy’s important new article (“Can Anyone Pacify the

World's Number One Narco-State?") deserves to mobilize Congress for a serious

revaluation of America’s ill-considered military venture in Afghanistan.

The

answer to the question he poses in his title - “Can Anyone Pacify the

World's Number One Narco-State?" - is amply shown by his impressive essay to

be a resounding “No!”... not until there is fundamental change in the

goals and strategies both of Washington and of Kabul.

He amply documents that,

-

the Afghan state of Hamid Karzai is a corrupt narco-state,

to which Afghans are forced to pay bribes each year $2.5 billion, a

quarter of the nation’s economy

-

the Afghan economy is a narco-economy:

in 2007 Afghanistan produced 8,200 tons of opium, a remarkable 53%

of the country's GDP and 93% of global heroin supply

-

military options for dealing with the problem are at best ineffective and

at worst counterproductive: McCoy argues that the best hope lies in

reconstructing the Afghan countryside until food crops become a viable

alternative to opium, a process that could take ten or fifteen years, or

longer.

(I shall argue later for an interim solution: licensing Afghanistan

with the International Narcotics Board to sell its opium legally.)

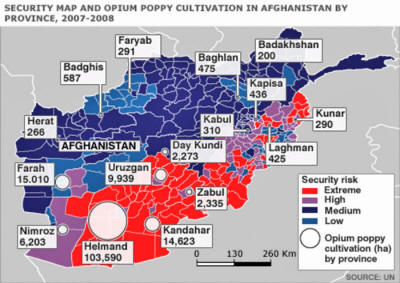

Map of Afghanistan showing major poppy fields and intensity of conflict

2007-08

Perhaps McCoy’s most telling argument is that in Colombia cocaine at its

peak represented only about 3 percent of the national economy, yet both the

FARC guerillas and the right-wing death squads, both amply funded by drugs,

still continue to flourish in that country.

To simply eradicate drugs,

without first preparing for a substitute Afghan agriculture, would impose

intolerable strains on an already ravaged rural society whose only

significant income flow at this time derives from opium. One has only to

look at the collapse of the Taliban in 2001, after a draconian Taliban-led

reduction in Afghan drug production (from 4600 tons to 185 tons) left the

country a hollow shell.

On its face, McCoy’s arguments would appear to be incontrovertible, and

should, in a rational society, lead to a serious debate followed by a major

change in America’s current military policy.

McCoy has presented his case

with considerable tact and diplomacy, to facilitate such a result.

The CIA’s Historic Responsibility for Global Drug Trafficking

Unfortunately, there are important reasons why such a positive outcome is

unlikely any time soon.

There are many reasons for this, but among them are

some unpleasant realities which McCoy has either avoided or downplayed in

his otherwise brilliant essay, and which have to be confronted if we will

ever begin to implement sensible strategies in Afghanistan.

The first reality is that the extent of CIA involvement in and

responsibility for the global drug traffic is a topic off limits for serious

questioning in policy circles, electoral campaigns, and the mainstream

media. Those who have challenged this taboo, like the journalist Gary Webb,

have often seen their careers destroyed in consequence.

Since Alfred McCoy has done more than anyone else to heighten public

awareness of CIA responsibility for drug trafficking in American war zones,

I feel awkward about suggesting that he downplays it in his recent essay.

True, he acknowledges that,

“Opium first emerged as a key force in Afghan

politics during the CIA covert war against the Soviets,” and he adds that

“the CIA's covert war served as the catalyst that transformed the

Afghan-Pakistan borderlands into the world's largest heroin producing

region.”

But in a very strange sentence, McCoy suggests that the CIA was passively

drawn into drug alliances in the course of combating Soviet forces in

Afghanistan in the years 1979-88, whereas in fact the CIA clearly helped

create them precisely to fight the Soviets:

In one of history's ironic accidents, the southern reach of communist China

and the Soviet Union had coincided with Asia's opium zone along this same

mountain rim, drawing the CIA into ambiguous alliances with the region's

highland warlords.

There was no such “accident” in Afghanistan, where the first local drug

lords on an international scale - Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Abu Rasul Sayyaf - were in fact launched internationally as a result of massive and ill-advised

assistance from the CIA, in conjunction with the governments of Pakistan and

Saudi Arabia.

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar (left)

and Abdul Rasul Sayyaf

While other local resistance forces were accorded second-class

status, these two clients of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, precisely because

they lacked local support, pioneered the use of opium and heroin to build up

their fighting power and financial resources.1

Both, moreover, became agents

of salafist extremism, attacking the indigenous Sufi-influenced Islam of

Afghanistan. And ultimately both became sponsors of al Qaeda.2

CIA involvement in the drug trade hardly began with its involvement in the

Soviet-Afghan war. To a certain degree, the CIA’s responsibility for the

present dominant role of Afghanistan in the global heroin traffic merely

replicated what had happened earlier in Burma, Thailand, and Laos between

the late 1940s and the 1970s.

These countries also only became factors in

the international drug traffic as a result of CIA assistance (after the

French, in the case of Laos) to what would otherwise have been only local

traffickers.

One cannot talk of “ironic accidents” here either.

McCoy himself has shown

how, in all of these countries, the CIA not only tolerated but assisted the

growth of drug-financed anti-Communist assets, to offset the danger of

Communist Chinese penetration into Southeast Asia. As in Afghanistan today

CIA assistance helped turn the Golden Triangle, from the 1940s to the 1970s,

into a leading source for the world’s opium.

In this same period the CIA recruited assets along the smuggling routes of

the Asian opium traffic as well, in countries such as Turkey, Lebanon,

Italy, France, Cuba, Honduras, and Mexico. These assets have included

government officials like Manuel Noriega of Panama or Vladimiro Montesinos

of Peru, often senior figures in CIA-assisted police and intelligence

services.

But they have also included insurrectionary movements, ranging

from the Contras in Nicaragua in the 1980s to (according to Robert Baer and

Seymour Hersh) the al Qaeda-linked Jundallah, operating today in Iran and

Baluchistan.3

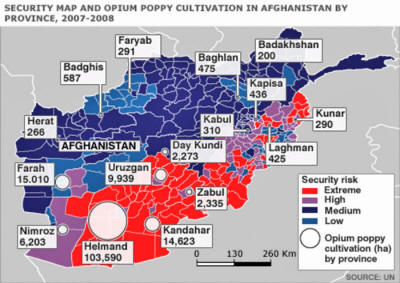

CIA map tracing opium traffic from Afghanistan to Europe, 1998.

The CIA

cite, updated in 2008 states,

“Most Southwest Asian heroin flows overland

through Iran and Turkey to Europe via the Balkans.”

But in fact drugs also

flow through the states of the former Soviet Union,

and through Pakistan and

Dubai.

The Karzai Government, not the Taliban, Dominate the Afghan Dope Economy

Perhaps the best example of such CIA influence via drug traffickers today is

in Afghanistan itself, where those accused of drug trafficking include

President Karzai’s brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai (an active CIA asset), and

Abdul Rashid Dostum (a former CIA asset).4

The drug corruption of the Afghan

government must be attributed at least in part to the U.S. and CIA decision

in 2001 to launch an invasion with the support of the Northern Alliance, a

movement that Washington knew to be drug-corrupted.5

In this way the U.S. consciously recreated in Afghanistan the situation it

had created earlier in Vietnam. There too (like Ahmed Wali Karzai a half

century later) the president’s brother, Ngo dinh Nhu, used drugs to finance

a private network that was used to rig an election for Ngo dinh Diem.6

Thomas H. Johnson, coordinator of anthropological research studies at the

Naval Postgraduate School, has pointed out the unlikelihood of a

counterinsurgency program succeeding when that program is in support of a

local government that is flagrantly dysfunctional and corrupt.7

Thus I take issue with McCoy when he, echoing the mainstream U.S. media,

depicts the Afghan drug economy as one dominated by the Taliban. (In McCoy’s

words, “If the insurgents capture that illicit economy, as the Taliban have

done, then the task becomes little short of insurmountable.”)

The Taliban’s

share of the Afghan opium economy is variously estimated from $90 to $400

million. But the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that the

total Afghan annual earnings from opium and heroin are in the order of from

$2.8 to $3.4 billion.8

Clearly the Taliban have not “captured” this economy, of which the largest

share by far is controlled by supporters of the Karzai government.

In 2006 a

report to the World Bank argued,

“that at the top level, around 25-30 key

traffickers, the majority of them in southern Afghanistan, control major

transactions and transfers, working closely with sponsors in top government

and political positions.” 9

In 2007 the London Daily Mail reported that,

"the

four largest players in the heroin business are all senior members of the

Afghan government."10

The American media have confronted neither this basic fact nor the way in

which it has distorted America’s opium and war policies in Afghanistan.

The Obama administration appears to have shifted away from the ill-advised

eradication programs of the Bush era, which are certain to lose the hearts

and minds of the peasantry. It has moved instead towards a policy of

selective interdiction of the traffic, explicitly limited to attacks on drug

traffickers who are supporting the insurgents.11

This policy may or may not be effective in weakening the Taliban.

But to

target what constitutes about a tenth of the total traffic will clearly

never end Afghanistan’s current status as the world’s number one narco-state.

-

Nor will it end the current world post-1980s heroin epidemic, which has

created five million addicts in Pakistan, over two million addicts inside

Russia, eight hundred thousand addicts in America, over fifteen million

addicts in the world, and one million addicts inside Afghanistan itself.

-

Nor

will it end the current world post-1980s heroin epidemic, which has created

five million addicts in Pakistan, over two million addicts inside Russia,

eight hundred thousand addicts in America, over fifteen million addicts in

the world, and one million addicts inside Afghanistan itself.

The Obama government’s policy of selective interdiction also helps explain

its reluctance to consider the most reasonable and humane solution to the

world’s Afghan heroin epidemic.

This is the “poppy for medicine” initiative

of the International Council on Security and Development (ICOS, formerly

known as The Senlis Council):

to establish a trial licensing scheme,

allowing farmers to sell their opium for the production of much-needed

essential medicines such as morphine and codeine.12

The proposal has received support from the European Parliament and in

Canada; but it has come under heavy attack in the United States, chiefly on

the grounds that it might well lead to an increase in opium production.

It

would however provide a short-term answer to the heroin epidemic that is

devastating Europe and Russia - something not achieved by McCoy’s long-term

alternative of crop substitution over ten or fifteen years, still less by

the current Obama administration’s program of selective elimination of opium

supplies.

An unspoken consequence of the “poppy for medicine” initiative would be to

shrink the illicit drug proceeds that are helping to support the Karzai

government.

Whether for this reason, or simply because anything that smacks

of legalizing drugs is a tabooed subject in Washington, the “poppy for

medicine” initiative is unlikely to be endorsed by the Obama administration.

Afghan Heroin and the CIA’s Global Drug Connection

There is another important paragraph where McCoy, I think misleadingly,

focuses attention on Afghanistan, rather than America itself, as the locus

of the problem:

At a drug conference in Kabul this month, the head of Russia's Federal

Narcotics Service estimated the value of Afghanistan's current opium crop at

$65 billion.

Only $500 million of that vast sum goes to Afghanistan's

farmers, $300 million to the Taliban guerrillas, and the $64 billion balance

"to the drug mafia," leaving ample funds to corrupt the Karzai government

(emphasis added) in a nation whose total GDP is only $10 billion.

What this paragraph omits is the pertinent fact that, according to the U.N.

Office on Drugs and Crime, only 5 or 6 percent of that $65 billion, or from

$2.8 to $3.4 billion, stays inside Afghanistan itself.13

An estimated 80

percent of the earnings from the drug trade are derived from the countries

of consumption - in this case, Russia, Europe, and America. Thus we should

not think for a moment that the only government corrupted by the Afghan drug

trade is the country of origin. Everywhere the traffic has become

substantial, even if only in transit, it has survived through protection,

which in other words means corruption.

There is no evidence to suggest that drug money from the CIA’s trafficker

assets fattened the financial accounts of the CIA itself, or of its

officers.

But the CIA profited indirectly from the drug traffic, and

developed over the years a close relationship with it. The CIA’s

off-the-books war in Laos was one extreme case where it fought a war, using

as its chief assets the Royal Laotian Army of General Ouane Rattikone and

the Hmong Army of General Vang Pao, which were, in large part,

drug-financed.

The CIA’s massive Afghanistan operation in the 1980s was

another example of a war that was in part drug-financed.

Video shows the CIA’s Hmong Army led by Gen. Vang Pao in action in Laos

Protection for Drug

Trafficking in America

Thus it is not surprising that the U.S. Government, following the lead of

the CIA, has over the years become a protector of drug traffickers against

criminal prosecution in this country.

For example both the FBI and CIA

intervened in 1981 to block the indictment (on stolen car charges) of the

drug-trafficking Mexican intelligence czar Miguel Nazar Haro, claiming that

Nazar was,

“an essential repeat essential contact for CIA station in Mexico

City,” on matters of “terrorism, intelligence, and counterintelligence.”14

When Associate Attorney General Lowell Jensen refused to proceed with Nazar’s indictment, the San Diego U.S. Attorney, William Kennedy, publicly

exposed his intervention. For this he was promptly fired.15

A recent spectacular example of CIA drug involvement was the case of the

CIA’s Venezuelan asset General Ramon Guillén Davila. As I write in my

forthcoming book, Fueling America's War Machine.16

General Ramon Guillén Davila, chief of a CIA-created anti-drug unit in

Venezuela, was indicted in Miami for smuggling a ton of cocaine into the

United States. According to the New York Times,

"The CIA, over the

objections of the Drug Enforcement Administration, approved the shipment of

at least one ton of pure cocaine to Miami International Airport as a way of

gathering information about the Colombian drug cartels."

Time magazine

reported that a single shipment amounted to 998 pounds, following earlier

ones “totaling nearly 2,000 pounds.”17

Mike Wallace confirmed that,

“the

CIA-national guard undercover operation quickly accumulated this cocaine,

over a ton and a half that was smuggled from Colombia into Venezuela.”18

According to the Wall Street Journal, the total amount of drugs smuggled by

Gen. Guillén may have been more than 22 tons.19

But the United States never asked for Guillén’s extradition from Venezuela

to stand trial; and in 2007, when he was arrested in Venezuela for plotting

to assassinate President Hugo Chavez, his indictment was still sealed in

Miami.20

Meanwhile, CIA officer Mark McFarlin, whom DEA Chief Bonner had

also wished to indict, was never indicted at all; he merely resigned.21

Nothing in short happened to the principals in this case, which probably

only surfaced in the media because of the social unrest generated in the

same period by Gary Webb’s stories in the San Jose Mercury about the CIA,

Contras, and cocaine.

Banks and Drug Money

Laundering

Other institutions with a direct stake in the international drug traffic

include major banks, which make loans to countries like Colombia and Mexico

knowing full well that drug flows will help underwrite those loans’

repayment.

A number of our biggest banks, including Citibank, Bank of New

York, and Bank of Boston, have been identified as money laundering conduits,

yet never have faced penalties serious enough to change their behavior.22

In

short, United States involvement in the international drug traffic links the

CIA, major financial interests, and criminal interests in this country and

abroad.

Antonio Maria Costa, head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, has said that,

“Drugs money worth billions of dollars kept the financial system afloat at

the height of the global crisis.”

According to the London Observer, Costa:

...said he has seen evidence that the proceeds of

organized crime were "the

only liquid investment capital" available to some banks on the brink of

collapse last year. He said that a majority of the $352bn (£216bn) of drugs

profits was absorbed into the economic system as a result...

Costa said

evidence that illegal money was being absorbed into the financial system was

first drawn to his attention by intelligence agencies and prosecutors around

18 months ago.

"In many instances, the money from drugs was the only liquid

investment capital. In the second half of 2008, liquidity was the banking

system's main problem and hence liquid capital became an important factor,"

he said.23

A striking example of drug clout in Washington was the influence exercised

in the 1980s by the drug money-laundering Bank of Credit and Commerce

International (BCCI).

As I report in my book, among the

highly-placed recipients of largesse from BCCI, its owners, and its

affiliates, were Ronald Reagan’s Treasury Secretary James Baker, who

declined to investigate BCCI;24 and Democratic Senator Joseph Biden and

Republican Senator Orrin Hatch, the ranking members of the Senate Judiciary

Committee, which declined to investigate BCCI.25

In the end it was not Washington that first moved to terminate the banking

activities in America of BCCI and its illegal U.S. subsidiaries; it was the

determined activity of two outsiders - Washington lawyer Jack Blum and

Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau.26

Conclusion

The Source of the Global Drug problem is not Kabul, but

Washington

I understand why McCoy, in his desire to change an ill-fated policy, is more

decorous than I am in acknowledging the extent to which powerful American

institutions - government, intelligence and finance - and not just the Karzai

government, have been corrupted by the pervasive international drug traffic.

But I believe that his tactfulness will prove counter-productive. The

biggest source of the global drug problem is not in Kabul, but in

Washington. To change this scandal will require the airing of facts which

McCoy, in this essay, is reluctant to address.

In his magisterial work, The Politics of Heroin, McCoy tells the story of

Carter’s White House drug advisor David Musto.

In 1980 Musto told the White

House Strategy Council on Drug Abuse that,

“we were going into Afghanistan to

support the opium growers in their rebellion against the Soviets. Shouldn’t

we try to avoid what we had done in Laos?” 27

Denied access by the CIA to

data to which he was legally entitled, Musto took his concerns public in May

1980, noting in a New York Times op-ed that Golden Crescent heroin was

already (and for the first time) causing a medical crisis in New York.

And

he warned, presciently, that “this crisis is bound to worsen.” 28

Musto hoped that he could achieve a change of policy by going public with a

sensible warning about a disastrous drug-assisted adventure in Afghanistan.

But his wise words were powerless against the relentless determination of

what I have called the U.S. war machine in our government and political

economy.

I fear that McCoy’s sensible message, by being decorous precisely

where it is now necessary to be outspoken, will suffer the same fate.

Articles on related subjects:

Notes

1 Eventually the United States and its

allies gave Hekmatyar, who for a time became arguably the world’s

leading drug trafficker, more than $1 billion in armaments. This was

more than any other CIA client has ever received, before or since.

2 Scott, The Road to 9/11, 74-75: “Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, said by the

911 Commission to have been the true author of the 9/11 plot, first

conceived of it when he was with Abdul Sayyaf, a leader with whom bin

Laden was still at odds [9/11 Commission Report, 145-50]. Meanwhile

several of the men convicted of blowing up the World Trade Center in

1993, and the subsequent New York “day of terror” plot in 1995, had

trained, fought with, or raised money for, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. [Tim

Weiner, “Blowback from the Afghan Battlefield,” New York Times, March

13, 1994].

3 Seymour Hersh, New Yorker, July 7, 2008

4 New York Times, October 27, 2009.

5 Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan,

and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (New York:

Penguin Press, 2004), 536. At the start of the U.S. offensive in 2001,

according to Ahmed Rashid, “The Pentagon had a list of twenty-five or

more drug labs and warehouses in Afghanistan but refused to bomb them

because some belonged to the CIA's new NA [Northern Alliance] allies”

(Ahmed Rashid, Descent into Chaos: The United States and the Failure of

Nation Building in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia [New York:

Viking, 2008], 320).

6 Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York: Penguin, 1997), 239. Cf.

New York Times, October 28, 2009.

7 Thomas H. Johnson and M. Chris Mason, “Refighting the Last War:

Afghanistan and the Vietnam Template,” Military Review,

November-December 2009, 1.

8 The alert reader will notice that even $3.4 billion is less than 53

percent of the $10 billion attributed in the previous paragraph to the

total Afghan GDP. These estimates from diverse sources are not precise,

and cannot be expected to jibe perfectly.

9 “Afghanistan: Drug Industry and Counter-Narcotics Policy,” Report to

the World Bank, November 28, 2006, emphasis added.

10 London Daily Mail. July 21, 2007. In December 2009 Harper’s published

a detailed essay on Colonel Abdul Razik, “the master of Spin Boldak,” a

drug trafficker and Karzai ally whose rise was “abetted by a ring of

crooked officials in Kabul and Kandahar as well as by overstretched NATO

commanders who found his control over a key border town useful in their

war against the Taliban” (Matthieu Aikins, “The Master of Spin Boldak,”

Harper’s Magazine, December 2009).

11 James Risen, “U.S. to Hunt Down Afghan Lords Tied to Taliban,” New

York Times, August 10, 2009: ”United States military commanders have

told Congress that... only those [drug traffickers] providing support to

the insurgency would be made targets.”

12 Corey Flintoff, “Combating Afghanistan's Opium Problem Through

Legalization,” NPR, December 22, 2005.

13 CBS News April 1, 2010, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/04/01/world/main6353224.shtml.

14 Cables from Mexico City FBI Legal Attaché Gordon McGinley to Justice

Department, in Scott and Marshall, Cocaine Politics, 36.

15 Scott, Deep Politics, 105; quoting from San Diego Union, 3/26/82.

16 Fueling America's War Machine: Deep Politics and the CIA’s Global

Drug Connection (in press, due Fall 2010 from Rowman & Littlefield).

17 Time, November 29, 1993: “The shipments continued, however, until

Guillen tried to send in 3,373 lbs. of cocaine at once. The DEA,

watching closely, stopped it and pounced.” Cf. New York Times, November

23, 1996 (“one ton”).

18 CBS News Transcripts, 60 MINUTES, November 21, 1993.

19 Wall Stree Journal, November 22, 1996. I suspect that the CIA

approved the import of cocaine less "as a way of gathering information"

than as a way of affecting market share of the cocaine trade in the

country of origin, Colombia. In the 1990s CIA and JSOC were involved in

the elimination of Colombian drug pingpin Pablo Escobar, a feat achieved

with the assistance of Colombia's Cali Cartel and the AUC terrorist

death squad of Carlos Castaño. Peter Dale Scott, Drugs, Oil, and War,

86-88.

20 Chris Carlson, “Is The CIA Trying to Kill Venezuela's Hugo Chávez?”

Global Research, April 19, 2007.

21 Douglas Valentine, The Strength of the Pack: The People, Politics and

Espionage Intrigues that Shaped the DEA (Springfield, OR: TrineDay,

2009), 400; Time, November 23, 1993. McFarlin had worked with

anti-guerrilla forces in El Salvador in the 1980's. The CIA station

chief in Venezuela, Jim Campbell, also retired.

22 The Bank of Boston laundered as much as $2 million from the

trafficker Gennaro Angiulo, and eventually paid a fine of $500,000 (New

York Times, February 22, 1985; Eduardo Varela-Cid, Hidden Fortunes: Drug

Money, Cartels and the Elite Banks [Sunny Isles Beach, FL: El Cid

Editor, 1999]). Cf. Asad Ismi, “The Canadian Connection: Drugs, Money

Laundering and Canadian Banks,” Asadismi.ws: “Ninety-one percent of the

$197 billion spent on cocaine in the U.S. stays there, and American

banks launder $100 billion of drug money every year. Those identified as

money laundering conduits include the Bank of Boston, Republic National

Bank of New York, Landmark First National Bank, Great American Bank,

People's Liberty Bank and Trust Co. of Kentucky, and Riggs National Bank

of Washington. Citibank helped Raul Salinas (the brother of former

Mexican president Carlos Salinas) move millions of dollars out of Mexico

into secret Swiss bank accounts under false names.”

23 Rajeev Syal, “Drug money saved banks in global crisis, claims UN

advisor,” Observer, December 13, 2009.

24 Jonathan Beaty and S.C. Gwynne, The Outlaw Bank: A Wild Ride into the

Secret Heart of BCCI (New York: Random House, 1993), 357.

25 Peter Truell and Larry Gurwin, False Profits: The Inside Story of

BCCI, the World’s Most Corrupt Financial Empire (Boston: Houghton

Mifflin, 1992), 373-77.

26 Truell and Gurwin, False Profits, 449.

27 Alfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin (Chicago: Lawrence Hill

Books/ Chicago Review Press, 2003), 461; citing interview with Dr. David

Musto.

28 David Musto, New York Times, May 22, 1980; quoted in McCoy, Politics

of Heroin, 462.