|

by Van Bryan

August 01, 2025

from

ClassicalWisdom Website

"There is nothing

either good or bad but thinking makes it so."

So run's a famous line

from Shakespeare's Hamlet.

Even now, it's a startling

concept:

the idea that morality

itself is non-existent, and entirely dependant on

our own minds and perspectives.

Yet the idea itself was

nothing new, even in the Bard's time. And yes, as with a

great many things, it has its roots in the ancients.

More specifically, it comes from ancient Greek

philosophy.

The Sophists were a controversial group of philosophers

who played a key role in the intellectual life of fifth

century Athens.

Socrates himself was a

vocal critic, and even today their ideas remain

influential and even 'dangerous'...

Yet there's no denying that their ideas changed the

world, for good or bad... if either of those things

really exist.

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom |

As

democracy came about in Athens

during the 5th century BCE, the city grew into

prosperity.

With the leadership of Pericles, Athens

ushered in a "Golden Age" of scholarship and culture that would be

marked with several advancements in the area of philosophy,

literature and politics.

During this time there was an established system

of law which, like our modern legal system, guaranteed an individual

his right to trial. Any man brought to court was allowed to plead

his case before a collection of judges who would consider an

appropriate ruling.

And while there was nothing in the way of formal

legal representation, there slowly emerged a group of legal

advocates that, for a fee, would act as advisors to the accused.

It was opportunities such as these that gave

birth to the group known as

the Sophists.

The Sophists were a collection of wandering teachers

that roamed Greece during the late 5th century,

dispensing wisdom and lectures for a fee.

And while many of them would find work as legal

advocates, many others lectured on subjects such as literary

criticism, poetry, and grammar. Still, their chief aim was to

provide training in rhetoric, persuasion, as well as the art of

winning over a crowd.

And while the Sophists were often criticized,

there remained great need for their services.

With the decline of aristocracy and the sudden rise of democracy,

rhetoric became extremely important to those with political

ambition. Politicians like Themistocles, were trained in the art of

rhetoric and persuasion and would gain

lofty political titles because of it.

Public speaking was also important to the average

citizen who always ran the risk of being brought to court where he,

and he alone, would be forced to defend himself with only the power

of his words.

Still, the Sophists are often remembered with

disdain...

Harsh criticisms were brought against them by the

likes of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle.

They were accused, and perhaps rightfully so,

of relying on persuasion and rhetoric to appear wise, without

actually pursuing any form of knowledge.

They could excite a crowd with their eloquent

prose, and persuade their listeners to agree with them, even

when possessing a weaker argument.

All the while they were accepting the coins

of their students, becoming rich from their lectures that often

dispensed untruth.

That isn't to say that all the Sophists were

thieves and con men.

Many of them were men who happened to possess a

particular mind set that had drawn them to sophism.

At the heart of sophism there is a universal

understanding that united them:

it was the belief that all truth is

relative...

It was this singular idea that possessed the

Sophists. Many of them used it as validation for making weaker

arguments strong, while collecting a fee all the while.

Others saw the philosophical implications of such

an idea.

"If you are ignorant of [what a Sophist

really is], you cannot know to whom you are entrusting your soul

- whether it is to something good or to something evil."

Plato (Protagoras)

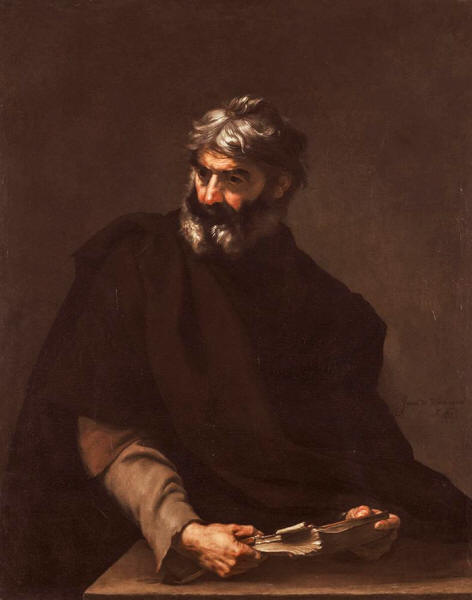

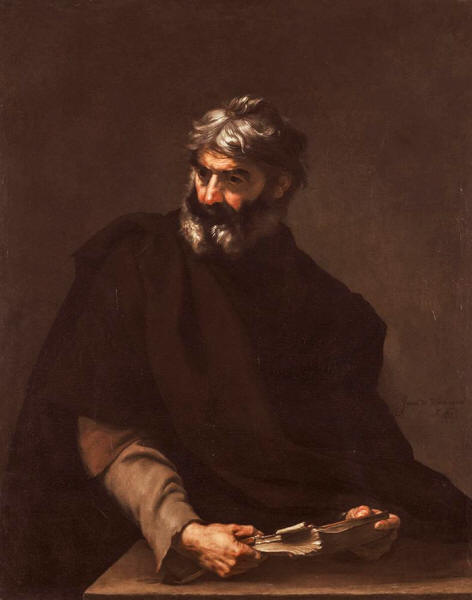

One of the most prominent of the Sophists was

Protagoras.

Protagoras

by Jusepe de Ribera,

1637

Born in Abdera, in northeast Greece.

He would spend much of his life traveling,

lecturing to anyone who could afford him. He would eventually travel

to Athens and become the advisor to the ruler Pericles.

A man who was a self proclaimed sophist,

Protagoras would put forth several ideas that expanded on the

loose doctrine of sophism. These ideas would expand to all areas

of human nature and would partially be supported by later

anthropological studies.

Although he admits to being a Sophist, Protagoras

is often remembered more as a pre-Socratic philosopher who

gave us the rather bold idea that,

man is the measure of all things...

As mentioned before, the Sophists rejected the

idea of objective truth.

Protagoras expanded on this and began examining

the essence of human nature and how it would relate to such abstract

notions such as justice, virtue and wisdom.

Having little to no interest in philosophical

speculation about the substance of the cosmos or the existence of

gods, Protagoras placed humans at the forefront of his philosophical

inquest.

By observing the Sophists arguing amongst each other, each

possessing different arguments yet each believing themselves to be

correct, Protagoras concluded that truth was very much a

matter of opinion.

The worth or value of an idea is determined

entirely by the person that holds it.

There exists no universal measure with which we

can compare ideas and accurately determine their worth, ideas and

their value are of a subjective nature, changing just as quickly as

a man changes his mind.

This might seem rather obvious when we take the time to reminisce

about ideas that we once held in such high regard.

As a child you undoubtedly thought it was a

good idea to stay up late, watch television and eat copious

amounts of candy. These ideas, at the time, were of great worth

to you; they were regarded very highly.

Yet, we all grow older and these ideas that we once held in high

regard are often eclipsed by our changing attitudes.

Political alliances, attitudes about love, as

well as commitment to a career are all aspects of ourselves that

undoubtedly change over the course of our lives.

And in this way we witness the subjectivity of

knowledge, the ever changing landscape of truth.

"No intelligent man believes that anybody

ever willingly errs or willingly does base and evil deeds; they

are well aware that all who do base and evil things to them

unwillingly."

Plato (Protagoras)

There are some rather important implications to

this idea of relativism.

If knowledge and truth are subjective, then

that would seem to suggest that ethical and moral behavior is

also relative...

And Protagoras again took this leap.

The philosopher believed that nothing was

inherently good or bad.

Something is only ethical or right

if a person or society judges it to be so.

Actions such as murder, theft,

even rape are immoral actions simply because our society

judges it to be so.

And if we take the time to deeply consider

this idea, we are cast into a very dark place

where all good and evil becomes equally

accessible, morally defensible if you have the right, or wrong,

mindset.

Socrates spent much of his life navigating

the philosophical terrain of objective ethical notions.

To Socrates, ideas such as justice

and virtue were not just passing considerations that

were reconfigured to meet one's preference. They were ideals that

existed eternally and without question or compromise.

Socrates sought to find these answers throughout

his life. And certainly there are some valid arguments against

Protagoras' ideas.

For instance,

mathematical properties should exist

eternally, regardless of the ideas of man.

Protagoras dismisses this, concluding that

mathematical principles do not necessarily exist in nature and

are therefore abstract ideas which need not concern us.

I can only assume that Pythagoras promptly

rolled over in his grave.

The confrontation between the philosophical ideas of Protagoras

and Socrates came to a head in Plato's

Protagoras,

a dialogue where Socrates and Protagoras, now

an old man, face each other to discuss the nature of virtue.

Protagoras, true to form, makes a very long,

very dramatic speech where he recounts the creation of man by

Prometheus.

Protagoras takes the stance that virtue can be taught, and that

the Sophists are doing a public service by educating the youth.

Socrates, of course, engages in a debate with

short, precise questions that he hopes will prove his own point.

The two philosophers eventually concede to

each other, complementing each other on their wisdom.

Yet, it would appear that Protagoras has won in a

subtle way...

Each man still holds different truths that are

validated by their own beliefs.

When Protagoras states that "man is the measure of all things" he

concludes that all knowledge, virtue, or wisdom

is determined by the the man or society that holds those beliefs.

On a warm summer day in Athens, a man from

Sweden will visit and comment that the climate is hot.

A man from Egypt will visit and comment that

it is so cold.

And yet, both of them are right.

This type of thinking was common within the legal

and political system of ancient Greece.

Our modern legal system similarly deals in

compromise, exceptions and reasonable doubts.

There are no absolutes.

The conclusion that Protagoras, as well as the

Sophists, drew was that there is nothing that is either right or

wrong, but thinking it will make it so.

There exists only man and the judgments that we

cast on ourselves...

|