|

by Peter Ripota

April 25, 2025

from

Medium Website

Combat everywhere.

Or is it the beginning of a lasting friendship?

Photo © Birger Strahl on Unsplash

'The world is a constant battle, and nature is red in tooth and claw',

...as the English poet Alfred Tennyson put it in 1850.

Isn't that true?

We only need to watch animal films on television.

Cheetahs hunt

antelopes to devour them afterwards, if hyenas are not faster.

Hyenas, in turn, are mercilessly hunted by lions, who also fight

each other to death.

Eagles eat snakes, snakes strangle eagles, and

giant snakes will swallow a whole pig.

Fighting everywhere!

However, the first animal films came from Walt Disney's workshop,

and he was a gifted storyteller. Today, these films follow the usual

Hollywood formula of sex and crime...:

hot kisses and sharp shots.

Because Americans are still as prudish as the English were in Queen

Victoria's time, there is not much sex to be seen.

So that leaves

the crime part, exploited to the full.

That's why we see so many

hunts and fights in these films.

Or would you like to see what the

animals are doing - dozing and sleeping for 23 hours of the day?

But see for yourself what is going on in nature.

As I write this, I

sit in a meadow before a bull enclosure.

Bees and other insects are

busily collecting nectar; ants are marking a road with their scents,

and butterflies are fluttering from flower to flower, drunk with the

smell they inhale.

Two bulls are measuring their strength, head to

head, but it doesn't look like a fight, more like a game.

A few

crows are sitting on posts and watching with interest, and the black

cat is sniffing the deep grass, maybe catching a grasshopper now and

then.

Where is the fight for existence?

Even in the jungle, things are not as the movies would have us

believe.

If an anaconda swallows a pig, it will last half a year,

maybe even a year.

However, if you want, you can find fighting and

extermination everywhere, even in the extremely courteous,

extraordinarily peace-loving and helpful Arabian Grey Thrush (Turdoides

squamiceps).

These nice birds outdo each other in friendliness.

They, too, have a hierarchy:

the nicer someone is, the higher they

get.

The adults raise the young together, feed each other, pet each

other, warm each other at night, and it is an honor to take on the

dangerous post of guard against eagles and snakes.

This honor is

only given to the highest-ranking male, but others are welcome.

How

did the inconspicuous flycatchers become so extremely altruistic,

especially since the groups are by no means only made up of related

individuals?

Why did Dawkins' "selfish genes" allow such apparent

misbehavior?

Why does everyone stick to these rules when cheating

would only benefit the cheater?

Biologist Amotz Zahavi from Tel Aviv

University investigated the matter and found some Darwinian

explanations.

His findings culminate in the astonishing statement:

Altruism is a selfish activity.

You have to let a sentence like that sink in. You surely know the

work of English author Eric Blair, who published "1984" in 1948

under the pseudonym George Orwell.

In it, he describes a

totalitarian state characterized by "doublethink" and thus produces

such beautiful sayings as "war is peace" or "freedom is slavery."

And now, the biologist mentioned above, representing many of his

profession, has found another saying from the world of the thought

police:

Altruism is egoism...

And that is science?

But we wanted to say something constructive.

Well then, it looks as

if the engines of evolution are not egoism and fighting but

communication and cooperation ("double-c" or c²), i.e.,

talking to

each other and working together.

The German philosopher Friedrich

Nietzsche already recognized this:

In nature, there is not a state of need but abundance and waste,

even to the point of senselessness.

Cooperation everywhere.

Photo © Getty Images via Unsplash

A Russian anarchist essentially advocated the c² idea, Count

Piotr

Alexeyevich Kropotkin, at the beginning of the 20th century.

As an

army officer in Siberia, he observed flora and fauna there for five

years.

The result of his observations:

the main factor for survival

in the harsh northern climate is not rivalry but mutual help.

Because:

If we ask nature, who is the most capable:

those who are always at

war with each other, or those who support each other?

Then we

immediately see that those animals that help each other are the best

adapted - the fittest.

They have a better chance of survival and

reach the highest level of intelligence and body structure.

The social revolutionary Kropotkin also identified mutual help as a

rule among people.

He predicted a trend in the modern world back to

decentralized, apolitical, and cooperative societies in which

everyone could be creative without the influence of bosses,

soldiers, priests, and other rulers.

This is very modern, indeed.

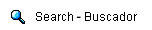

We owe the big breakthrough of the c² idea to a woman.

Lynn Margulis

applied the c² concept to cells.

Biologists have long been puzzled

by one component of cells.

Mitochondria, the energy suppliers of

every cell, have their hereditary structure. They pass on their

genes through the maternal line.

Margulis concluded that

mitochondria were originally independent life forms absorbed by

other living beings, but not eaten.

The two communicated and formed

an alliance to cooperate:

the larger cell protected the smaller one,

which in turn gave energy to the larger one.

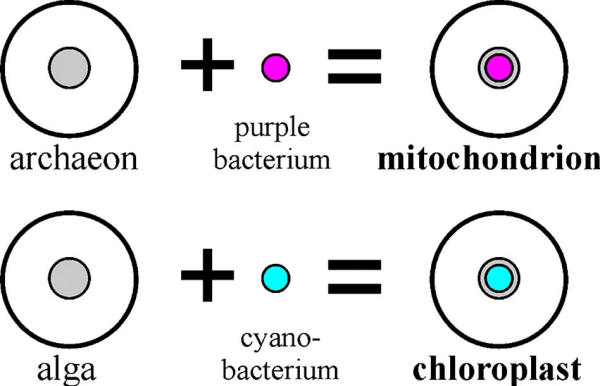

There are many other examples of this type of

endosymbiosis:

-

Bacteria and archaea (primitive life forms similar to bacteria)

merged to form mitochondria, the power plants of cells.

While most

bacteria can absorb dissolved organic compounds and use them to

generate energy for their metabolism, archaea lack these transport

systems in their membranes.

Bacteria and archaea probably first

attached themselves to one another, and the latter used the

bacteria's waste products to generate energy.

Before the

relationship could become more intimate, the bacteria had to

transfer their genes for the membrane's transport systems to the

archaea.

Only now were the archaebacteria able to absorb dissolved

organic compounds themselves, which ensured the bacteria's survival

in the host cell.

Over time, the bacteria passed more and more of

their genes to the host so that only a few genes remained, as in the

case of the mitochondrion.

-

Algae and cyanobacteria merged to form higher plants.

A host cell

absorbed cyanobacteria. The host cell could lead a different life by

ingesting the photosynthetically active symbiont because it could

suddenly live on light, water, and CO2.

-

The organelles of many algae have three or four membranes. The

researchers assume that cells were repeatedly devoured but not

digested, etc...

The emergence of

mitochondria

and chloroplasts via "symbiogenesis".

The big cell (left) captured but did not digest

a special bacterium

protected by an additional membrane.

Image by author

In all life forms, there is genuine cooperation between individuals.

Here are a few examples:

-

When conditions become evil for a certain species of amoeba (Dictyostelium

discoideum), they do not eat each other until the fittest remain.

On

the contrary, they join a highly cooperative activity called slime

mold aggregation. They form a fruiting body in which numerous

individuals climb on top of each other until a kind of superpenis is

formed.

Around 20% of the individuals that form this stem die; the

rest turn into spores blown away by the wind and - hopefully - one

day find fertile soil.

The amoebas that formed the hardcore and died

sacrificed themselves entirely unselfishly.

Slime mold (Comatricha nigra).

Source: Creative Commons

-

Yeast cells die a selfless suicide (scientifically: apoptosis) for

altruistic reasons, namely when nutrients become scarce, and

everyone is in danger of starving.

Through such a mass suicide, one

in ten cells or just one in a million cells can survive.

-

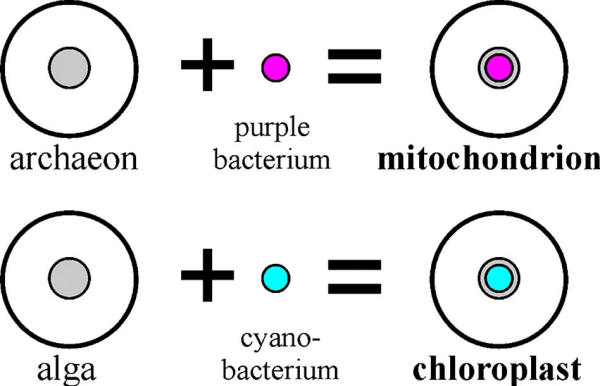

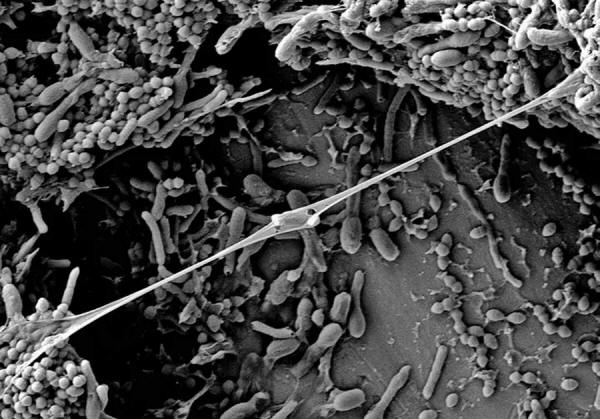

The most fantastic manifestation of c², however, is the complex

cities built by mindless microorganisms - in your mold!

These

structures, known as biofilms, are built by bacteria, algae, fungi,

and single-celled organisms (e.g., paramecia).

They join together in

colonies, check the environmental conditions, count their neighbors,

and create three-dimensional city structures comparable in

complexity to modern cities, which, as one scientist once

enthusiastically noted, "look like Manhattan at night."

There are

water pipes, sewers, shipping channels, and assembly areas. An

extreme example is the colonies that live in the stomachs of cows.

Five forms of bacteria ensure the breakdown of cellulose:

Strain 1

converts cellulose into glucose. Strain 2 uses glucose to make

butyrate.

This substance is transformed by the 3rd strain into

acetate, which Strain 4 feeds on and produces methane as a

byproduct.

Oxygen is poisonous for all four strains, and there is

much of it in a cow's stomach.

Therefore, a fifth type of bacteria

creates a protective film around the other four so that they can

work and live undisturbed.

Not only are the life forms that build such cities extremely

primitive (according to our anthropocentric point of view), but they

also belong to different species that certainly do not "speak" the

same language.

These life forms are extreme examples of

communication (they must agree on who builds and manages what) and

cooperation (they manage and supply their city together).

How do

they do it - and above all, why...?

Where is the selection pressure,

the supposedly everywhere effective struggle for existence, the

ruthless selection of the weak, the survival of the strong?

Why do

selfish genes allow such mixing?

Scanning electron micrograph of a biofilm.

© Krzysztof A. Zacharski,

Creative Commons

Finally,

the ability to communicate and

cooperate also seems to guarantee the economic survival of people and nations.

At least,

that is what the Japanese-American economist Francis Fukuyama ("The

End of History") claims, and he puts forward good arguments.

The

northern and central European peoples are doing well economically:

their c² ability is very well developed...

This applies to the

Americans and Japanese but not to southern Italians and Chinese.

Where everyone distrusts everyone else and only their family members

are trustworthy, neither a flourishing economy nor a cultural life

can develop.

In these countries, there are only three powerful

institutions:

Therefore, according to Fukuyama,

the Chinese will never

become an economic competitor to other states despite their vast

human resources and hard work, despite everybody else telling us

otherwise...

The old ruling dynasty of the Habsburgs knew about this

principle.

Instead of perpetual wars, they pursued a successful

marriage policy as a secondary strategy.

Hence the saying:

"Others may wage wars, but you, happy

Austria, marry!"

Conclusion:

The ability to cooperate seems to offer

long-term

survival advantages...!

|