|

by Meghan Bartels

March 20, 2024

from

ScientificAmerican Website

|

Meghan Bartels

is a science journalist

based in New York City. She joined Scientific American

in 2023 and is now a senior news reporter.

Previously, she spent more

than four years as a writer and editor at Space.com, as

well as nearly a year as a science reporter at Newsweek,

where she focused on space and Earth science.

Her writing has also

appeared in Audubon, Nautilus, Astronomy and

Smithsonian, among other publications.

She attended Georgetown

University and earned a master's in journalism at New

York University's Science, Health and Environmental

Reporting Program. |

An image of Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks

and its rotating core

taken by Jan Erik Vallestad.

Comet

12P/Pons-Brooks

is hiding a

strange spiral in its icy heart

and it may tell

scientists

about the

comet's innards...

Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks is a

shapeshifter...:

in the summer of 2023 it sported wings like

the Millennium Falcon, the iconic Star Wars ship.

By autumn it had been dubbed the "Devil

comet" for its horned appearance...

Source

Now, for astro-photographers with the right

equipment, Comet 12P appears to hide a perfect spiral - and the

stunning sight could tell scientists more about this particular ice

ball, which is one of the brightest comets on record.

Still, it can be tricky to observe and

photograph.

Comet 12P is trekking toward its closest approach

to the sun, set

to occur in late April, so

currently, it never rises high above the horizon and competes with

the dregs of sunlight.

"I didn't have any high expectations at all

because when I started the sessions each day, you could still

see the sunlight on the horizon," says

Jan Erik Vallestad, an

amateur astro-photographer based in Norway.

"I thought I would probably get just the

coma - a blob."

(A coma is the fuzzy-looking cloud

surrounding the icy nucleus, or core, of a comet and is created by

gas and dust lifted off its surface.)

But Vallestad got much more than a blob:

in an image taken on March 9, he captured not

only the comet's long wispy tail streaking across the sky but

also a spiral feature that he was able to highlight in editing.

Source

As bizarre as the phenomenon looks, it's real,

says Quanzhi Ye, a planetary astronomer at the University of

Maryland, who noted that he and his colleagues have also seen the

feature in Comet 12P.

The spiral is far from unprecedented:

astronomers had begun noticing that the

hearts of certain comets contained a spiral as early as 1858.

And its explanation is surprisingly simple, Ye

says.

"We know that comets release gas and dust

into space, and the nucleus is also rotating just like any

celestial object," he says.

The shed gas and dust become the coma,

which reflects sunlight and gives a comet's core its characteristic

blurry appearance.

When different parts of the comet's surface lose

material at different rates, the coma can become uneven. And

because the comet's nucleus is spinning, the brighter and fainter

parts of the coma twist into a spiral.

That formation story means the spiral isn't just pretty...

Scientists can work back in time, starting from

the visual pattern, to learn more about the comet.

"We can use spiral features like this to try

to get a sense of how fast and in what direction the nucleus is

rotating," Ye says.

"It tells us a whole lot about the comet

itself, which is pretty amazing."

Comet 12P is an exciting comet to learn more

about, he says.

It's particularly prone to outbursts of gas and

dust, which can make it appear bright in the sky.

Although the spiral pattern isn't triggered by an

outburst, Ye says, skywatchers hope the comet might undergo an

outburst in the next few weeks that could make it bright enough to

see during the total solar eclipse that will cross North America on

April 8.

In addition, this object hails from an especially interesting cohort

of comets, dubbed Halley-type comets after their most famous

member:

Source

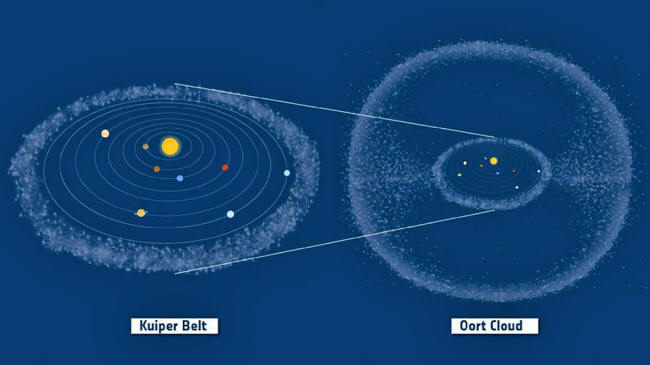

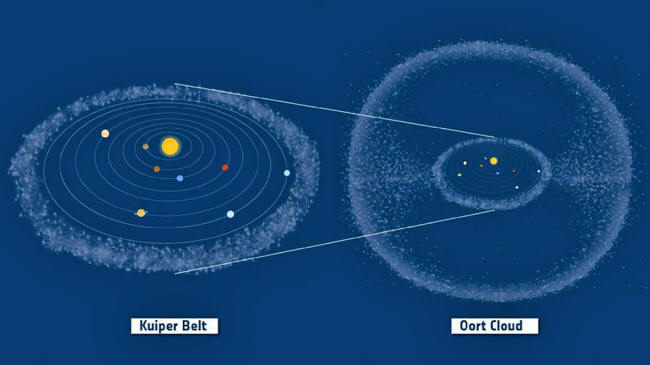

These comets swing through the solar system once

every 20 to 200 years - Comet 12P clocks in at a 71-year orbit.

Short-period comets with orbits that are less than 20 years long

come from the

Kuiper belt region beyond Neptune.

Long-period comets with orbits that are more than

200 years long come from the spherical

Oort cloud in the cold outer

reaches far beyond.

Being able to study more Halley-type comets

could help scientists understand the area between these two

comet-laden regions, Ye says.

Comet 12P is also a witness to the ways skywatching has grown and

changed since its last pass through the inner solar system, which

occurred from 1953 to 1954, Ye says.

"Last time it was around, we didn't have so

many telescopes; we didn't have modern computers to give us this

information," he says.

This time, humans have many more observatories,

and a particularly powerful one should catch Comet 12P's retreat:

the

Vera C. Rubin Observatory

in Chile should begin its sky survey next year.

And even when the comet lurks too close to the

horizon, where science facilities struggle to observe it, amateur

astronomers around the globe are eager to monitor the ice ball and

share what they see.

"That's kind of the beauty of it all, I

think," Vallestad says of astrophotography, which he began doing

in earnest about two years ago.

"Not only do you get to create images that

can be aesthetically pretty to look at, but you can also bring

forth scientific information as well."

|