|

CHAPTER SIX

The place where these first cities suddenly arose was ancient Mesopotamia, in the fertile plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, where the country of Iraq now lies.

The civilization was called Sumer, the “birthplace of writing and the wheel”,’ and from its very beginning it bore a striking resemblance to our own civilization and culture today. The highly respected scientific journal National Geographic clearly recognizes the primacy of the Sumerians and the legacy which they left to us. There, in ancient Sumer... urban living and literacy flourished in cities with names such as Ur, Lagash, Eridu and Nippur. Sumerians were early users of wheeled vehicles and were among the first metallurgists, blending metals into alloys, extracting silver from ore, and casting bronze in complex molds.

Sumerians were also the first to invent writing. The National Geographic also acknowledges:

All studies of the Sumerians have stressed the extremely short period within which their high level of culture and technology arose.

One author described it as “a flame which blazed up so suddenly”,’ whilst Joseph Campbell eloquently stated,

Why then is there a widespread lack of public awareness regarding the Sumerians?

A clue may lie in the fact that the source of their civilization remains a complete mystery to conventional science. History books are forced to gloss over Sumerian origins by simply referring to their emergence, as if no further explanation is necessary. This treatment is adopted by the highly respected The Times Atlas of World History, which is so embarrassed to admit its ignorance, that it ignores the Sumerians (the most important civilization of all!) and talks instead of the vague “emergence” of a “Mesopotamian” first civilization.’

The mystery is summed up by one National Geographic Society publication, which states:

Nevertheless, many attempts have been made to portray the origin of the Sumerians as an evolution from pre-existing cultures in Mesopotamia.

These studies focus on pottery, and demonstrate that the people from Sumer had already lived in the area for thousands of years. However, they have little to offer on the question of why it suddenly became necessary for men to live in organized cities.

The best explanations are inevitably vague and floundering:

Such explanations are as contrived as the theories of mankind’s sudden evolution.

Whilst the brain is the Achilles heel of the evolutionists’ arguments, so the Sumerians’ technology is the Achilles heel of the historians’ arguments. The scholarly obsession with creating a smooth and gradual cultural development ignores the amazing aspects of Sumerian metallurgy, mathematics and astronomy (inter alia) which all arose in perfect form at the beginning of their civilization.

Regarding the origin of that knowledge, it would

seem that only the Sumerians themselves can solve the mystery that

confounds the scientists. And the Sumerians attributed their

success, indeed their very origin, to flesh-and-blood Gods.

This chapter, dealing with the Sumerian mystery, is an appropriate point on which to conclude our round-up of the mysteries of heaven and Earth, and to begin our study of the solution. At a superficial level, Sumer provides scholars with yet another unsolved mystery, but at a detailed level there lie vital clues to explaining the many mysteries and anomalies in the world today.

This chapter is

the tale of the Sumerians and their Gods.

There was without doubt, a strong Sumerian influence

in those other civilizations, for the Sumerians were keen travellers

and explorers. For the purpose of this book, it is not necessary to

prove that the earliest civilizations on Earth were offshoots from

the first civilization of Sumer, but there is ample evidence that

this was the case.

Spurred on by Biblical clues, the accounts of earlier travellers and by local folklore, archaeologists such as the Paris-born Englishman Sir Austen Henry Layard indeed found their fame and fortune. It was a Frenchman who made the first important discovery.

In 1843, Paul

Emile Botta uncovered fantastic temples, palaces and a ziggurat

(step-pyramid) at a site identified as Dur-Sharru-Kin, the eighth

century BC capital of Sargon II, king of Assyria. Today the site is

called Khorsabad. Botta will always be remembered as the discoverer

of the Assyrian civilization.

In 1835, Rawlinson had carefully copied a vital trilingual

inscription on a stone slab found at Behistun in Persia; in 1846, he

deciphered the script and its languages, one of which was Akkadian,

common to the Assyrians and the Babylonians, who had inherited the

Near East after the collapse of Sumer c. 2000 BC.

One inscription, listing the achievements of an earlier ruler, Sargon I, claimed that he was the “King of Akkad, King of Kish”, and that he had defeated in battle the cities of “Uruk, Ur and Lagash”.

Scholars were amazed to

find that this Sargon had preceded his later namesake by nearly two

thousand years, taking the Mesopotamian civilization back to at

least 2400 BC.

In

1869 Jules Oppert first proposed the prior existence of a “lost”

Sumerian language and people. As with all new ideas, it took some

time to become fully accepted. Whilst the so-called ‘’Sumerian

Question” raged through the latter part of the nineteenth century,

the first Sumerian cities began to be excavated and speculation

turned to established scientific fact.

Further

south, the hot and dusty wasteland of Uruk yielded the world’s first

ever ziggurat, dedicated to the Goddess Inanna, as well as examples

of some of the earliest inscribed writing.

It was at Ur that the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley discovered exquisite works of gold, silver and lapis lazuli including the “ram in a thicket’’ (Figure 36), the beautiful Queen’s Harp (the oldest harp ever found, dating from 2750 BC) and a splendid head-dress all of which can now be seen at the British Museum.

It was at Eridu, however, almost 200 miles south-east of Baghdad that the earliest Sumerian city was found. The city of Eridu is nowadays an abandoned, windswept wilderness, dominated by the ruins of Ur-Nammu’s ziggurat. The city’s ruins spread over an area measuring 1.300 by 1,000 feet.

Here, beneath the foundations of its first temple, dedicated to the God Enki, archaeologists found virgin soil, marking the very beginning of civilization on Earth. This temple was dated to 3800 BC, the same time that the world’s first calendar began at Nippur.

By the early twentieth century, all but one of the Assyrian cities mentioned in the Old Testament had been found. The city of Babylon, too, had been excavated, although little remained of the ziggurat dedicated to its chief God Marduk.

The royal city of Kish was also discovered, along with other important Sumerian sites such as Larsa. Shuruppak, Sippar and Bad-Tibira. The full linkage between Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylon remains a mystery to the historians, but the study of their written scripts has confirmed the primacy of the Sumerians. Many Akkadian texts directly stated that they were copies of earlier originals; one tablet, for example, found in Nineveh by Layard, referred to the “language of Shumer not changed’’.

Scholars found that the Akkadian

script used a large number of “loan-words” in referring to subjects

such as astronomy, science and the Gods.” These loan-words indicated

an earlier and fundamentally different writing system, known as

“pictographic”, where single signs represented objects or concepts

by the use of pictures. It has now been established that the

original Sumerian writing system was indeed based on pictographic

signs, similar to those later used in Egypt.

Consequently, it is now widely

accepted that Sumer was the first

advanced civilization on Earth, and the

date of its beginning is unanimously

agreed to be 3800 BC.

Many deal with the humdrum routine of daily life -marriage and divorce records, school grammar and vocabulary texts, and commercial contracts, the latter dealing with matters such as the recording of crops, the calculation of prices and the movement of goods.

Records such as these have given scholars a remarkable insight into Sumerian culture.

One of the foremost experts on Sumer is Professor Samuel Noah Kramer, who has travelled the world to study, copy and translate their texts. In his book History begins at Sumer, he listed 39 Sumerian “firsts”.

In addition to the first writing system which we

have already discussed, his firsts included the first wheel, the

first schools, the first bicameral congress, the first historian,

the first “farmer’s almanac’’, the first cosmogony and cosmology,

the first proverbs and sayings, the first literary debates, the

first “Noah”, the first library catalogue, the first money (the

silver shekel “weighed ingot”), the first taxation, the first law

and social reforms, the first medicine, and the first search for

world peace and harmony.

Evidently, society suffered from many of

the same ills as ours, for c. 2600 BC it was necessary for a king

named Urukagina to order the first legal reform to prevent the abuse

of supervisory power, official status and monopoly position.

Urukagina claimed that it was his God Ningirsu who had ordered him

to “restore the decrees of former days”.

The library of Ashurbanipal, which Layard discovered in Nineveh, was carefully organized, with a medical section containing thousands of clay tablets. All of the medical terms were based on Sumerian loan-words. Medical procedures were outlined in text books, dealing with hygiene, operations such as the removal of cataracts and the use of alcohol for surgical disinfection.

Sumerian medicine was marked by a highly scientific

approach of diagnosis and prescription for either therapy or

surgery. Sumerian construction was also highly advanced, within the

constraints of locally available building materials. From the very

beginning in 3800 BC, houses, palaces and temples were constructed

of specially strengthened bricks, manufactured by combining wet clay

with reeds.

The

range of these materials is astonishing, including gold, silver,

copper, diorite, carnelian and cedar wood. In some cases these

materials were transported more than a thousand miles.

This process, called smelting, became necessary at

an early stage, when the supply of naturally occurring copper

nuggets had been exhausted. Independent studies of early metallurgy

have been surprised and baffled at the speed with which the

Sumerians became expert in smelting, refining and casting. These

advanced technologies were being used within only a few hundred

years of the beginning of the Sumerian civilization.

The alloying of copper with tin was an incredible achievement for three reasons. First, it was necessary to use a very precise mixture of copper and tin (analysis of Sumerian bronze has established an optimum ratio of 85 per cent copper and 15 per cent tin). Secondly, tin was not available in any quantity in Mesopotamia. Thirdly, tin does not occur in a natural state and requires a complicated process to extract it from cassiterite ore.

This is not the sort of thing one discovers by accident.

The

Sumerians used thirty different words to describe different

qualities or types of copper, and their word for tin,

AN.NA,

literally meant “Heavenly Stone”, once again indicating that

Sumerian technology was a gift of the Gods.

The evidence also suggests that they knew the planets of the Solar System before they were “discovered” in modern times (see chapter 7).

Thousands of clay tablets, found at Nineveh, Nippur and other Sumerian sites, have been found to contain hundreds of astronomical terms. Some of these tablets included mathematical formulae and astronomical tables, which enabled the Sumerians to predict solar eclipses, the phases of the Moon and the movements of the planets.

Studies of ancient astronomy have demonstrated the remarkable accuracy of these tables (known as ephemeredes). No-one knows how they could have calculated such sophisticated data and we might well ask why they needed it. Several studies have suggested that the ziggurat, the hallmark of Sumerian architecture, may have also served an astronomical purpose.

These structures contained a square

base with corners perfectly aligned to the four cardinal points of

the compass. One scholar has therefore suggested that they were

ideal for astronomical observation:

We also owe to the Sumerians the division

of the heavens into three bands - the northern, central and southern

regions (corresponding to the ancient Sumerian “way of Enlil”, “way

of Anu” and “way of Ea”). In fact, the whole concept of spherical

astronomy, including the 360-degree circle, the zenith, the horizon,

the celestial axis, the poles, the ecliptic, the equinoxes etc, all

arose suddenly in Sumer.

The Sumerian calendar was thus carefully constructed to ensure that key days such as New Year’s Day always occurred on the spring equinox, and did not slip back as they do in other calendars. It is difficult to imagine a more complex calendar than that of the Sumerians. and later calendars were indeed much simpler. It is quite improbable that the first calendar, at Nippur, was the most complex and yet there is no doubt whatsoever that this was so. Indeed, the whole subject of Sumerian astronomy is most intriguing, for the simple reason that it was not a necessity for an emerging society.

Allied to the Sumerians’ interest in astronomy was the

world’s first

known mathematical system. This system was highly advanced, and

included the “place” concept, whereby a digit could take on a

different value depending on its place in the overall number (as “1”

can mean 1, 10, 100 and so on). However, unlike our present-day

decimal system, the Sumerian system was sexagesimal.

As unwieldy as the Sumerian base 60 system might at first seem, it enabled the Sumerians to divide into fractions and multiply into the millions, to calculate roots or to raise numbers by several powers. In many respects it is superior to the base 10 system which is used today, due to the fact that 60 is divisible by ten integers whereas 100 is only divisible by seven integers.

In addition, it is the only perfect system for geometry, and this explains its continued use in modern times - hence the 360 degrees in a circle. Few people realize that we owe not only our geometry but also our modern time-keeping systems to the Sumerian base 60 mathematical system.

The origin of

60 minutes in an hour and 60 seconds in a minute is not arbitrary,

but designed around a sexagesimal system. Sumerian numerology is

similarly evident in the 24 hours in a day, the 12 months in a year,

the 12 inches in a foot and the dozen as a unit. Its legacy also

appears in modern numbering systems which comprise separate,

distinct numbers from 1 to 12, followed by expressions for 10 + 3,

10 + 4, and so on.

As can be seen from Figure 15b, the Earth’s twelve month journey around the Sun changes the starry backdrop, forming a great 360-degree circle.

The zodiac was created by dividing this circle into twelve equal parts (zodiac houses) of 30 degrees. The stars in each house were then grouped into constellations and given a name. The original Sumerian names of each house, paralleling the modern names, have now been found, proving beyond any doubt that the zodiac’s first use was in Sumer.

The nature of the zodiac signs (for

which the star-pictures are wholly contrived), together with the

arbitrary division into twelve, prove beyond any doubt that the

identical zodiacs used in other, later, cultures, could not have

been independent developments.

The lack of any connotations, other than astronomical, for the multiples of 25,920 and 2,160 can only suggest a deliberate design for astronomical purposes.

The uncomfortable question which the scientists have avoided is this:

Gods of the Shems

Why did the Sumerians go to such incredible lengths to build ziggurats aligned to the cardinal points of the compass? Why was the role of astronomer and priest combined?

Furthermore, why was it so important to divide the Earth’s celestial cycle by the number twelve? It is a number which brings us back to the Sumerians’ central claim: “whatever seems beautiful, we made by the grace of the Gods”.

Those Gods, like the Greeks’ Gods millennia later, were organized in a pantheon of twelve.

So pervasive is the influence of the Gods in Sumerian culture that one archaeologist was moved to comment that the “Gods bequeathed the Earth to mankind”, whilst Professor Samuel Kramer, one of the greatest authorities on Sumer, observed that:

Naturally, we are not supposed to take Samuel Kramer’s comment literally.

Similar observations are found liberally spread throughout the academic press, presented, almost without exception, under a banner of Sumerian mythology and religious belief. This belief system, like everything else in Sumer, was incredibly detailed and sophisticated. The whole of Sumerian life revolved around the Gods, whom they regarded as flesh-and-blood immortals.

Kings were chosen and could assume the throne only with the

permission of the Gods. In later times, battles were fought on the

Gods’ behest. And the Gods also provided specific instructions to

build and rebuild temples in particular locations.

However, such facile solutions leave unexplained the origin of the Sumerians’ sophisticated scientific knowledge. Inventing Gods is one thing, but inventing the technology to measure the movements of the planets and stars is another thing entirely ! If we give due recognition to the “impossible” origin of Sumerian knowledge, as well as to the other mysteries of the world covered in chapters 1-5, a possible solution begins to emerge.

Could all of these anomalous technologies have a common source? Can we continue to dismiss the Sumerians’ claim that their civilization was a gift of the Gods? Let us take a closer look at those Sumerian Gods.

Whilst the term “Gods” is full of awkward connotations for us, the Sumerians did not suffer from such problems, and referred to them as the AN.UNNA.KI, literally meaning,

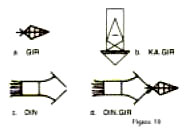

They also described them pictographically as DIN.GIR. What does the term DIN.GIR mean?

In 1976, Zecharia Sitchin published a detailed etymological study of this, and other, terms used by the Sumerians and later civilizations to describe the rockets and craft of the Gods.

The pictographic sign for GIR (Figure 16a) is commonly understood to mean a sharp-edged object, but an insight into its true significance can be gleaned from the sign for KA.GIR (Figure 16b) which appears to show the aerodynamically-shaped GIR inside a shaft-like underground chamber.

The sign for the first syllable DTN (Figure 16c) makes little sense until it is combined with GIR to form DIN.GIR (Figure 16d).

The two syllables. when written together, make a perfect fit, representing, in Sitchin’s words:

As with the Apollo rockets, three sections can be seen in the pictographic sign DIN.GIR - the lowest stage propulsion unit with the main thrust engines, the middle stage containing supplies and equipment and the upper stage command module.

The full meaning of DIN.GIR, usually translated “Gods”, is conveyed more fully by Sitchin’s translation as “The Righteous Ones of the Blazing Rockets”.

Zecharia Sitchin’s study also identified a second, different type of aerial vehicle. Whilst the GIR appeared to describe the rocket-like craft required for journeys beyond Earth’s atmosphere, another vehicle known as a MU was used to fly within the Earth’s skies. Sitchin pointed out that the original term shu-mu, meaning “that which is a MU”, later became known in the Semitic language as shem (and its variant sham).

Drawing on the earlier work of G. Redslob, he pointed out that the terms shem and shamaim (the latter meaning “heaven”) both stemmed from the root word shamah, meaning “that which is highward”. Because the term shem also had the connotation “that by which one is remembered”, it came to be translated as “name”.

Thus an unchallenged translation of an

inscription on Gudea’s temple reads “its name shall fill the

lands”,” whereas it ought to read more literally as “its MU shall

hug the lands from horizon to horizon”. Sensing that shem or

MU

might represent an object, some scholars have left the word

untranslated.

If we substitute the literal meaning of shem as “sky vehicle”, the unintelligible tale in Genesis (the significance of which has always puzzled scholars) begins to take on a new meaning:

The proper meaning of shem also casts new light on another section of Genesis which has always puzzled scholars, and which is highly significant to our study of the Gods. In this example, the traditional translation of shem as “name” is replaced by “renown”, on the basis that if one makes a name for himself, one is renowned.

The passage which follows also includes reference to the mysterious Nefilim, a Hebrew word often mistranslated as "Giants” but which actually comes from a root word meaning “Those Who Descended”.

The meaning closely parallels the meaning of the Sumerian AN.UNNA.KI “Those Who from Heaven to Earth Came”:

The Nefilim, then, were not the men of renown, but “the people of the shem” - the Gods of the sky vehicles.

There is one more example

of linguistic confusion that I would like to cover, and that

concerns the unfortunate association of Gods with heavenly bodies.

The association of Gods with the Sun, Moon and visible planets has

enabled scholars to dismiss the flesh-and-blood Gods as a set of

primitive beliefs. A classic example of this is the confusion which

has arisen concerning the worship of a Sun God, both in ancient

Egypt and the Near East.

Historians dismiss the ancient belief in these two sacred sites as a primitive form of Hellos/Sun worship. However, let us take a closer look at where the legend of Hellos the Sun God came from. Both Heliopolises were important sites for the Gods, for reasons which will become clear in chapter 8, and both were associated with a God known to the Akkadians as Shamash. Sumerian texts called him UTU, a God who controlled the sites of the shems and the "eagles”.

The name Shamash, when spelled Shem-esh, literally means "shem-fire” and is thus often translated as “He Who is Bright as the Sun”. The Sumerian name UTU indeed meant “the Shining One”, whilst Mesopotamian texts described Utu/Shamash as rising and traversing the skies.

It is not difficult to see how

the accounts of these journeys could subsequently be misconstrued as

the daily movement of the Sun!

During the last one hundred years, scholars have been fascinated by the rich body of epic literature recovered by the archaeologists in Mesopotamia. That fascination has led to a determined and painstaking effort to piece together texts which are sometimes only recovered in fragments.

Original Sumerian texts have been

supplemented by later and similar Akkadian versions, allowing the

full reconstruction of many ancient tales. What has emerged is a

detailed and coherent picture of anthropomorphic Gods with

human-like emotions, intimately mixed up in human affairs. Scholars

have been left in no doubt that the origin of the Greek tales of

Zeus, Olympus and the pantheon of twelve Gods lies in Sumer.

A review of these sites provides us with the most important names, to whom the temples were dedicated:

The same names, or their Akkadian equivalents, also crop up again and again in the later Assyrian and Babylonian cities.

It is clear that these names bestowed meanings which were based on

human perceptions of certain aspects of these Gods, and they thus

appeared under different nicknames to reflect different attributes

and powers.

The Sumerians sometimes called it “The House for Descending from Heaven”. When kingship was first granted to man by the Gods (an antecedent for today’s royal families), it was referred to as the “Anu-ship” Anu had two sons who descended to Earth. Although they were brothers, they sometimes fought as bitter rivals.

The firstborn son, Enki, was the first to take command on Earth, only to be displaced on Anu’s orders by the second-born son Enlil.

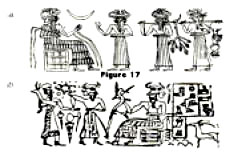

Ancient depictions of the Gods Enki and Enlil are shown (seated) in Figure 17a and 17b respectively, emphasizing their flesh-and-blood nature and humanlike appearance.

The brotherly rivalry hinged on the Gods’ legal rules of succession, which were determined by genetic purity. Enlil, the offspring of Anu and his half-sister, thus preserved the father’s genes through the male line far better than Enki.

This practice, of marrying half-sisters, seems rather incestuous to us today, but it was not always so.

For example, it was also a common practice by the

royal families in Egypt,

whilst in the Bible, Abraham, too, boasted that his wife was also

his sister. The origin of

this practice undoubtedly lies in the realm of the Gods, and I will

explain the scientific basis

behind it in a later chapter.

Enlil’s city was Nippur, at which a magnificent E.KUR, a “House like a Mountain”, was built, and fitted with mysterious equipment that could survey the heavens and Earth. Its five-storey ruins can still be seen today, one hundred miles south of Baghdad. His brother EN.KII meaning “Lord of Earth” was also known as E.A, “He Whose House is Water”.

His city was Eridu, on the waterfront where the Tigris and Euphrates meet the head of the Persian Gulf. He was the master engineer and chief scientist of the Gods, and mankind’s greatest benefactor. He often defended man in the council of the Gods, and saved Noah and his family from the great Flood.

Why was Enki so friendly towards mankind? According to the Sumerians, it was Enki who played an instrumental role in man’s creation. Although regarded by scholars as myth, the Sumerians firmly believed that the Gods had created man as a worker. The ancient texts describe a rebellion of the rank-and-file Gods in protest at their heavy workload (the exact nature of this work will be discussed in chapter 14).

Enki then settled the dispute by offering to create a primitive worker and “bind upon it the image of the Gods” so that it was intelligent enough to use tools and follow instructions. Enki was assisted in the creation of man by his half-sister NIN.HAR.SAG, meaning “Lady of the Head Mountain”. She was the chief nurse in charge of the Gods’ medical facilities, and hence one of her nicknames was NIN.TI, “Lady Life”.

Together, she and Enki carried out genetic experiments, with varying degrees of success. The texts relate that Ninharsag was responsible for a man who could not hold back his urine, a woman who could not bear children and another being with no sexual organs. Enki also had his failures, including one man with failing eyesight, trembling hands, a diseased liver and a weak heart!

Given our own twentieth century decoding of the human genome, we can understand the excitement and power felt by Ninharsag, who in one text exclaimed:

Finally the perfect man was created.

Ninharsag cried out,

One text states quite explicitly that Ninharsag gave the new creation “a skin as the skin of a God”.

Having perfected the ideal man with a larger brain, enhanced digit ability and smooth skin, it was a simple next step to use cloning - now an established scientific process - to produce an army of primitive workers. This fantastic event was commemorated for all time by Ninharsag’s symbol - the horseshoe-shaped cutter of the umbilical cord, an instrument that was used by midwives in ancient times.

She also became known as the Mother Goddess, and became associated with numerous primitive religious cults throughout the ancient world.

Archaeologists have long been puzzled by the sacred representation of the pregnant female form by the earliest societies. In the first chapter, I described the meaning of terms such as “clay/dust”, “rib” and the newly created being which the Sumerians called LU.LU - a term which literally meant “one who has been mixed”.

In the light of the fundamental contradictions of mankind’s evolution, covered in chapter 2, the Sumerian account takes on a tremendous significance. Did Enki bind the image (the genetic blueprint) of the Gods upon the lowly Home erectus, which suddenly experienced the incredible evolutionary leap to Home sapiens 200,000 years ago?

A very detailed study of the ancient

texts suggests that this was, indeed, exactly what happened.

These terms clearly indicate the role of the Gods as Guardians or Lords over mankind.

Scholars have tended to study the Sumerian and Egyptian civilizations as independent subjects, but as we shall see, the prehistory of mankind knew no such boundaries. One of the best known and fascinating Egyptian legends is that of Osiris and Isis. Although generally regarded as myth, mainstream scholars have occasionally suggested that it might be based on historical events.

According to Manetho, an Egyptian priest cum historian from the third century BC, the God Osiris and his sister-wife Isis were rulers over the land of northern Egypt more than six thousand years before human civilization began. As we shall see, the tragic tale of Osiris sheds considerable light on a key event in mankind’s prehistory.

The tragic tale begins with Osiris being tricked by his own brother Seth into lying in a large chest, which Seth then seals and throws into the sea. Isis, overcome by grief, goes in search of her missing husband.

She is informed by a divine “wind” that the chest has been blown ashore at Byblos in Lebanon. Whilst she is waiting for the help of the God Thoth to resurrect the body, Seth appears again, dismembers the body into fourteen pieces and scatters them all over Egypt. Once again Isis goes in search of her husband and manages to find all of the body parts except his phallus.

Some

legends say that Isis then buried the parts where she found them,

others that she bound them together, thus starting the tradition of

mummification. The tale continues with what appears to be an account

of cloning, as Isis extracts the “essence” from the body of Osiris

and uses it to impregnate herself. She then secretly gives birth to

the child Horus, who grows up and returns to avenge the death of his

father.

The battle ends with the defeat and exile of Seth, a God who was thereafter associated with chaos. Prior to 1976, the Egyptian and Mesopotamian accounts had been studied separately and largely from a mythological perspective.

Then one scholar, Zecharia Sitchin, taking the translations at face value, linked the accounts together into a consistent and credible sequence of events. In so doing, he turned Egyptian mythology into the earliest period of human history, and showed how the Horus/Seth conflict led to a ferocious war between the rival factions of Enlilite and Enkiite Gods. Why was there such hatred between the brothers Osiris and Seth?

Applying the same rules of succession

found in the Sumerian tales, Sitchin demonstrated that by marrying

Isis, Osiris effectively prevented his rival Seth from producing an

heir from the same half-sister. Until that time, the rivalry between

Osiris and Seth had been solved by splitting the land of Egypt

between them. Now Osiris had ensured that it would be a son of his,

not Seth’s, that would assume the future rule of the whole of Egypt.

After the Flood - for the Sumerians recognized it as a genuine historic event - the texts state that the Earth was divided into four regions - a neutral zone of the Gods on the Sinai peninsula, entrusted to the mother Goddess Ninharsag; the African lands under the supervision of the Enkiite Gods; and the lands of Asia, particularly Mesopotamia and the Levant, under the supervision of the Enlilite Gods.

As Zecharia Sitchin has shown, this division of lands accords with the legend that a great God named Ptah arrived in Egypt from overseas and undertook reclamation works, to raise the land above the waters. It was on this account that the ancient Egyptians named their country the “Raised Land”.

All of the evidence suggests, with little doubt, that this God was

Enki.

Scholars have been mystified by the Biblical story which, whilst unintelligible, clearly appears to be of major importance. As one commentator notes, Genesis 9 “refers to some abominable deed in which Canaan seems to have been implicated.

Citing the ex-biblical Book of Jubilees, Sitchin suggests that Canaan’s abominable deed was to have strayed from the lands which had been preordained for him:

How could Canaan have so easily defied the instructions of the Gods that assigned the African lands to the Hamitic people?

As Sitchin points out, his action would surely not have been possible without the connivance of one or other major deity. It is therefore a strong possibility that Canaan’s abominable deed coincided with the occupation of Lebanon by the God Seth and his supporters, fleeing from the battle with Horus.

In Zecharia Sitchin’s view, it was this illegal occupation of Enlilite land that led to a full-scale war in which the Enlilites drove the Enkiite Gods out of Canaan. The war is described in numerous Sumerian, Akkadian and Assyrian texts, which scholars collectively refer to as the “Myths of Kur”.

It is also alluded to in Egyptian ritual texts, one of which refers to,

However, far from being

myths, these tales represent a genuine

account of one of the crucial events in the history of man, who was

called up for the first time to fight for his Gods.

The final scene of the battle was the E.KUR, the “House Like A Mountain”, to which the Enkiite Gods had fled, led by Enki, Ra and Nergal (and later joined by Horus). Although they were safe behind the Ekur’s powerful protective shield, the Enkiite Gods were effectively under siege, trapped with little food and water.

Why did one group of Gods launch such a bitter and bloody war against their fellow Gods? First, we should note the deep antagonism which divided the descendants of Enlil and Enki. As discussed earlier, the firstborn son Enki was extremely jealous of his brother Enlil, who was the legal heir to Anu.

It should be recalled that, when the Gods had first settled on Earth, aeons before kingship and civilization were granted to mankind in Sumer, Enki had been displaced by Enlil, and we know from the Atra-Hasis epic that he was sent to a region known as “the Abzu”.

As

we shall see in a later chapter, the term Abzu denoted the African

lands, including Egypt. Enki was therefore resentful of his demoted

status and relegation to the African lands.

The eventual outcome of the war was a humiliating surrender and one-sided peace conference. which was to have far-reaching repercussions.

As for the

fate of Canaan and his clan, the Old Testament records that, instead

of being moved to their designated lands, they were allowed to stay

in the Middle East with a lower status, as servants to the Shemitic people whilst the lands of Japheth were to be extended.

Her promiscuous exploits were a favorite subject of the ancient scribes, and her physical attributes were extremely popular with the ancient artists! Hundreds of texts have been found dealing with Inanna’s love affairs, one of the best known examples being The Epic of Gilgamesh.

As the archetypal Goddess of love, she was known to all of the ancient civilizations under a variety of different names. To the Assyrians and Babylonians she was known as Ishtar, to the Canaanites as Ashtoreth, to the Greeks as Aphrodite and to the Romans as Venus. According to the Sumerian texts, she was the daughter of Nannar, the grand-daughter of Enlil and the great-granddaughter of Anu.

She was also known by many other nicknames, such as IR.NI.NI “The Strong Sweet-smelling Lady”.

Inanna’s sexual passions were rivalled only by her prowess on the battlefield, hence she became known as the archetypal Goddess of war, as well as the Goddess of love. In many ways these two qualities went hand-in-hand. Her tale, unfolded by Zecharia Sitchin in The Wars of Gods and Men, is a tragic one, beginning with her marriage to Dumuzi, a son of Enki.

Whether this was a true love match, or an attempt by Inanna to gain power in the rival Enkiite lands, we cannot be certain. But in those early days, her power in Enlilite country was certainly blocked by male domination.

One does not need to be a feminist to sense her frustrated ambitions; her grandfather Enlil had overall command; her brother Utu was in charge of the key site at Jerusalem; her father Nannar was in charge of Sinai and her uncle ISH.KUR (meaning “FarMountain Land”) had always been ultimately responsible for the important site at Baalbek.

Her own power-base in Sumer was

limited to the city of Uruk, which at that time

carried very little status.

The dramatic capture, escape and unfortunate death of Dumuzi are dealt with in the Sumerian text known as His Heart Was Filled With Tears. The ensuing trip by Inanna to Africa (the Lower World) is one of the most famous of all Sumerian texts, and was dutifully copied by the ancient scribes. Figure 18 shows a tablet from the Akkadian version.

The death of Dumuzi, combined with the

position of Africa in the Lower World (southern hemisphere), have

naturally led to Inanna’s “descent” being viewed as a mythological

tale of a trip to the underworld or realm of the dead. This view has

been reinforced by legends that it was a place from which men did

not return, but in the case of Inanna, it was very much a land of

the living from which she did return.

We know from one text that Ra took refuge inside a “Mountain” described as E.BIH “The Abode of Sorrowful Calling”. Another text describes it as the same E.KUR in which the Enkiite Gods had been besieged by Ninurta. Zecharia Sitchin once again lifts the veil of myth to describe a historic event - the ensuing trial of Ra, his imprisonment inside the Ekur without food or water, and his subsequent escape.

There is little doubt that Inanna was left bitter and frustrated by the death of Dumuzi and the blocking of her ambitions in Africa. Her consolation prize, as suggested by Sitchin, was to be given control over a new civilization, in the Indus Valley (modern Pakistan).

This mysterious civilization first emerged at various sites c. 2800 BC and was in full bloom by 2500 BC. The striking feature of this culture, known as Harappan, was its homogeneity in all aspects of life, such as building, pottery and religious belief. Its principal cities, Harappa and Mohenjodaro, were laid out in a manner that has led archaeologists to think that they “were conceived in their entirety before they were built”.

Significantly, the Harappan religious beliefs were very different from the Sumerians and Egyptians who worshipped many Gods.

In contrast, the Harappans worshipped a sole female deity (Figure 19), whose depictions bore an amazing similarity to other images of the Goddess Inanna.

However, Inanna was soon to grow bored with her new responsibilities, and she then turned her attention back to Sumer.

During a visit to Enki at his home in the Abzu, Inanna got him drunk and tricked him into giving her certain divine objects known as “ME’s”. Exactly what these objects were is unknown, but they bestowed great knowledge and power on Inanna.

Whilst her Harappan civilization was busy repairing the damage from recurring floods, her Sumerian city Uruk suddenly became very powerful and Inanna herself became a major deity. It was then, according to the ancient texts, that Inanna found the man who was to be the instrument of her ambitions, the man who established the city of Agade and subsequently founded the Akkadian empire.

The man’s name was Sargon the Great, and the archaeological date c. 2400 BC.

The era of Inanna

was about to begin, and in both love and war, she was’ to become

more dangerous than ever before.

Sumer is unable to impress us like the Egyptian pyramids - its ancient ziggurats are barely recognizable mounds - but the legacy of Sumerian technology reaches out and touches us continuously. Every time we check our watch, we should think of the Sumerian base 60 mathematics and its close connection with Sumerian astronomy.

Whenever we drive our cars, we should remember the first Sumerian wheel. In all our established institutions, we should recognize the Sumerian legacy. Those thousands of tiny Sumerian clay tablets, which are quietly tucked away in our museums, speak far more lucidly than the hieroglyphics on public display in Egypt.

The story they tell is powerful and compelling, offering solutions even to the mystery of mankind himself. Let us examine some facts.

Now let us examine some options: either the Sumerians were telling the truth, or they were lying.

If the Sumerians were lying (or at least being rather

imaginative), then we still have to explain where they acquired

their technology. If their teachers were not “extraterrestrials’’

then they were terrestrials. The latter implies a prior civilization, perhaps the popular idea of a lost

civilization of

Atlantis, which taught itself over tens of thousands of years and

then was destroyed in a cataclysm. We have a simple choice - Gods or

Atlanteans!

In previous chapters, we have studied many examples of ancient

technology - in ancient maps, in the pyramids, in various other

sites and their astronomical alignments. This same ground is covered

by supporters of the Atlantis theory

- the theory that everything can be explained by a lost civilization.

But at this point, chapter 6, we must part company with the

supporters of Atlantis, for it is the intention of this book to deal

in hard evidence, not unsubstantiated myth, rumor or speculation.

As the famous Carl Sagan once said:

The following chapters will therefore concentrate on physical evidence which corroborates the Sumerian texts.

There are several crucial questions which we need to ask.

The feasibility of very slow ageing, giving the appearance of immortality, is examined in chapters 12 and 13, based on the latest discoveries from genetic science.

Finally, in order to establish the role of flesh-and-blood Gods in human history, we must satisfy the basic need for a chronology that will link all events together in a form that can survive the most rigorous of examinations.

The basis for such a chronology is set out

in chapter 11 and further developed in chapter 13.

That question is

taken up in chapters 15 and 16.

|