|

December 2025 from RT Website

December 16, 2025

Events in Ukraine have taken on the feel of a Shakespearean tragedy as one after another in Zelensky's inner circle has fallen or fled under the taint of corruption.

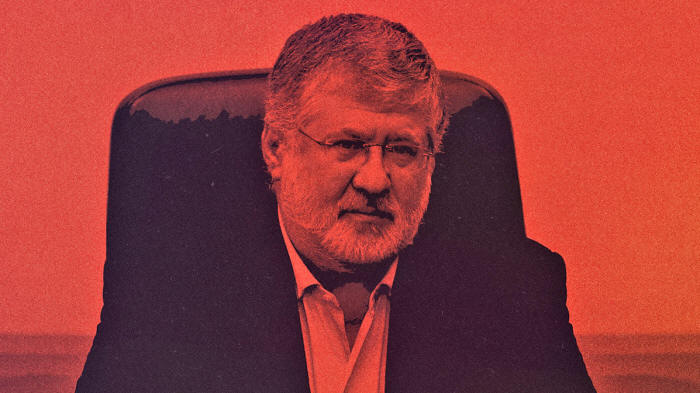

Perhaps it would be fitting if Kolomoysky ends up with the last word in this sordid affair, for it was his efforts that gained Zelensky the presidency in the first place.

When the oligarch himself finally met his

comeuppance, into the breech stepped another Kolomoysky-made man,

Timur Mindich, who would reconstruct much of his former

benefactor's patronage network for equally corrupt aims.

Yet, Kolomoysky seems to stand upstream from the

entire intertwined morass of militant nationalism, cronyism, and

corrupt patronage networks that have defined modern Ukraine.

Even as late as 2006, a team of individuals hired

by Kolomoysky, armed and wielding chainsaws, took over the

Kremenchuk Steel Plant.

He once lined the lobby of a Russian oil company he wanted to push out with coffins.

In his office, he maintained a shark tank

equipped with a button that, in the presence of disconcerted

visitors, he would push to dispense bloody meat into the water.

Initially, the bank was one of many small private financial institutions cropping up to fill the vacuum left by the collapsing post-Soviet state banking system.

Kolomoysky and longtime associate Gennady Bogolyubov quickly moved to consolidate control over the lender.

Over the course of the next decade, they did

exactly that, buying out other shareholders, and using profits from

their assorted commercial interests to inject capital into the bank.

However, far removed from the shiny green retail outlets and ubiquitous ATMs was the bank's seamy underside:

A key part of that structure was a secret

internal unit named BOK headed up by loyal confidantes.

The bank became the personal laundromat of

Kolomoysky and Bogolyubov through which they extracted billions of

dollars.

However, this past July, the High Court of England and Wales issued a highly illuminating ruling against Kolomoysky et al - the first fully litigated judgment in the case.

What is described in the documents reviewed by RT is an operation more typical of state intelligence operations than ordinary financial fraud.

This was an unusually elaborate, industrial-scale

fraud, even by the standards of major bank scandals.

What was concocted was nothing less than a

full-scale alternative reality.

These borrowers - many with no credit history, a

single employee, and balance sheets that wouldn't cover office rent

- were in fact shell firms created and controlled by PrivatBank's

owners, Igor Kolomoysky and Gennady Bogolyubov.

The numbers were surreal.

One firm, Esmola LLC, was granted the equivalent of $16.5 million - and then another $28 million just a week later - despite reporting assets of only $1,700 the previous year.

Other contracts required suppliers to deliver volumes of product that defied physics:

All contracts required 100% prepayment, with no collateral, no performance guarantees, and no commercial logic.

And that was the point...

In the early stages, some of the sham suppliers cycled the prepayments back to PrivatBank, allowing the same money to slosh repeatedly through the system.

By late summer 2014, the returns stopped.

The prepayments were no longer coming back, and

nearly $2 billion disappeared into offshore entities controlled by

the bank's shareholders.

In other words, assets much less likely to arouse suspicions of ill-gained wealth.

Politico documented how he bought a

small-town Midwestern factory and let it go to seed.

The bank was named as a defendant because the borrowers also sought to invalidate the sham supply agreements provided as security for the loans.

The bank centrally prepared all the paperwork for

these lawsuits and also bore the legal costs itself even as it was a

defendant in the cases.

But none of the judgments were ever enforced.

It is surely no coincidence that most of the

lawsuits were filed in Dnepropetrovsk's Economic Court - at the

exact time the region was headed up by none other than Kolomoysky

himself.

Ukrainian media outlet Glavcom would later

publish a

crucial early investigation based

on the publicly-accessible choreographed legal filings exposing how

over $1 billion had ended up in opaque foreign accounts as a result

of PrivatBank's activities.

A 2018 investigation by the corporate intelligence firm Kroll concluded that,

The events that unfolded over the next three

months, resulting in the violent overthrow of Ukraine's

democratically elected president, would come to be known simply as 'Maidan'.

Those killed during the protests are memorialized as martyrs (the Nebesna Sotnya or 'Heavenly Hundred') with a quasi-religious reverence.

Yet behind the democratic, youth-inflected veneer

of the Maidan protests lurked darker and more malevolent forces that

would shape the course of events in fateful ways.

Overnight November 29-30, the Ukrainian elite riot police force, Berkut, violently dispersed the remaining several hundred Maidan protesters in a move that had the effect of galvanizing and radicalizing the protest movement.

The following day, hundreds of thousands

descended on Maidan.

Burning debris and other objects were hurled at

the security forces, injuring 21 officers.

Key to the puzzle is the enigmatic figure of

Sergey Lyovochkin, the head of Yanukovich's administration at

the time.

Inter TV reported the clashes as an

unprovoked beating of defenseless, peaceful student protesters by

police. The station that happened to be on site in the dead of night

was coincidentally

co-owned by the very same

Lyovochkin.

Lyovochkin was the most senior of those who

neither fled nor was prosecuted, suggesting he may have been

collaborating with the protest movement and thus was subsequently

protected by the Maidan government.

It was a story repeated but with far higher stakes in several months' time when 48 Maidan protesters were shot to death by snipers on Maidan and an adjacent street.

The killings, which were reflexively attributed

to Berkut forces by Western and pro-Maidan media, were the

single most radicalizing event of the entire protest movement, and

they directly triggered the rapid escalation that culminated with

Yanukovich being driven from power.

A ruling in 2023 by the Ukrainian Sviatoshyn District Court even confirmed some of the activists had been killed not by Berkut special police forces but actually by snipers holed up in the Hotel Ukraina, at the time occupied by Right Sector extremists, and other Maidan-controlled locations.

The verdict also established that no evidence

exists for any order by Yanukovich or his government to fire upon

the Maidan protesters.

The oligarch, who had supported the Maidan events and referred to himself as a "die-hard European," would soon become the largest sponsor of far-right militias in the country...

Several months after Maidan, an oligarch, Pyotr Poroshenko, was elected president.

As commentator Joshua Yaffa put it,

Poroshenko's tenure would prove a failure.

Reverting, as Yaffa explained, to the,

...Poroshenko also broke a campaign promise to sell his lucrative confectionery company.

Even more ominously, he undermined the work of the newly created, Western-run anti-corruption agency, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine, or NABU.

He would not be the last Ukrainian president to

stymie this essentially Western-run mechanism aimed at reining in

Ukraine's corrupt leadership.

This circumstance would be revealed in all of its

significance when, four years later, Poroshenko ran for reelection

against Vladimir Zelensky...

Robbing Peter

to pay Paul - How Kolomoysky 'defended' the Country he was Looting

A week later, the country's interim leadership

appointed Kolomoysky head of Dnepropetrovsk Region, long seen

as something of a personal fiefdom for the oligarch.

By the middle of 2014, Ukraine's banking sector was experiencing a full-blown crisis, and dark clouds were gathering over PrivatBank. Amid large customer withdrawals and weakening capital liquidity, Bogolyubov and the lender's CEO, Alexander Dubilet, wrote to the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) in July requesting a stabilization loan worth about $200 million.

This came at a time when Ukraine was negotiating

a $17 billion IMF program that had many strings attached, one being

a cleanup of the country's banking sector.

By the time Kolomoysky took over as governor, groups opposed to the Maidan coup had already seized control of government buildings in neighboring provinces and anti-Maidan demonstrations were taking place in Dnepropetrovsk.

The oligarch-cum-governor moved quickly to quash

this sentiment.

Experts estimate that it cost

Kolomoysky upwards of $10 million a month just to fund the militia

and police units, some of which technically reported to Ukraine's

army and Interior Ministry.

According to the High Court ruling,

PrivatBank's loan misappropriation scheme only ceased in

September 2014 - seven months after Maidan.

Svyatoslav Oleynik, a former deputy governor under Kolomoysky, admitted that the oligarch had,

Several of the post-Maidan far-right paramilitary

units became notorious for

heinous crimes in the eastern

regions of Ukraine.

Indeed, Dnepropetrovsk became a bulwark of the pro-Ukrainian movement. However, his efforts were widely seen in another light.

Kolomoysky's fondness for personal militias eventually got the better of his judgment.

The oligarch owned a non-controlling stake in national oil producer Ukrnafta, but as he often did, he had managed to insert his own management team and thus had the run of the place.

The company owed millions of dollars in dividends to the government, but was refusing to pay.

When in March 2015, the parliament passed a law

that would allow the state to appoint new management, Kolomoysky

sent a private militia to take over the company's headquarters and

built an iron fence around its perimeter.

Subsequently, the NBU gave the bank several deadlines to fix the multitude of problems, starting with low-quality loans to parties affiliated with the shareholders and ending with worthless collateral on those loans.

The NBU would eventually find that 97% of

PrivatBank's corporate loans were issued to companies linked to its

shareholders.

The NBU demanded either proof that these

borrowers were independent or a restructuring of the loans.

To preserve secrecy, they reused an internal coding system already employed within the bank's offshore network:

The meaning of these codes (mere employees acting

as nominee owners) could only be deciphered using a separate

spreadsheet created months earlier in the bank's Cyprus branch.

Kolomoysky and his cronies had two main tasks:

They failed miserably on both counts.

The two shareholders also agreed to make various asset transfers to the bank's balance sheet to prop it up, but did so at preposterously inflated valuations.

Kolomoysky and Bogolyubov seemingly assumed

paperwork alone would satisfy regulators, without any verification

of the real asset value. It was an assumption that had worked for

years.

The word 'nationalization' was hovering in the

chilly autumn air of Kiev...

The private jet of Kolomoysky was tracked leaving

the country the night of the announcement. Bogolyubov, incidentally, would not flee Ukraine until 2024, using forged documents to board an economy-class train car to Poland.

Recapitalizing the bank would cost the Ukrainian state an astounding 6% of GDP.

An independent corporate investigator concluded that at least $5.5 billion was stolen from the bank over the course of a decade. But it did not spell the end for Kolomoysky or of corruption among those in his orbit.

Kolomoysky would be back to seek revenge...

His return ticket would be stamped with the name:

Additional information from The New York Times.

December 18, 2025

Zelensky Elected - The People's

Fantasies and Kolomoysky's favor

It was an instance of life imitating art. In a TV series called 'Servant of the People', Zelensky played the role of a school teacher who launches a quixotic bid for the presidency running as an anti-corruption crusader.

The series, which became wildly popular, aired on the TV channel

1+1, majority owned by Kolomoysky's 1+1 Media Group.

He did, however, promise to stop the war in Donbass and, being a Russian speaker himself, opposed the rigid language policies of Poroshenko. But otherwise, there wasn't much there.

Ukrainian sociologist Irina Bereshkina called him,

That, in addition to the support of Kolomoysky, proved to be his

biggest advantage.

His campaign slogan was "Army, language, faith."

However, coverage on Kolomoysky's channel overwhelmingly favored Zelensky. The informal manager of Zelensky's campaign was none other than Andrey Bogdan, the lawyer who represented Kolomoysky in the PrivatBank affair.

Bogdan would be Zelensky's first chief of staff before being pushed

aside in favor of

Andrey Yermak.

The offshore entities funneled Kolomoysky's money through the

British Virgin Islands, Belize, and Cyprus in order to avoid paying

taxes in Ukraine. According to the documents, associates of Zelensky

used these entities to purchase and own three high-end properties in

London.

He

claimed that $41 million from

PrivatBank was transferred, through a series of intermediary

companies, to the accounts of Kvartal 95 while the bank was still

controlled by Kolomoysky. Ariev called the scheme, whereby money

would be lent to entities ultimately controlled by the oligarch

himself, standard practice for Kolomoysky.

Kolomoysky was hardly shy about how his protégé's victory was perceived:

Zelensky was inaugurated on May 20, 2019.

Three days later, the Ukraine Crisis Media Center published a rather starkly worded list of '25 Red Lines Not To Be Crossed', ostensibly on behalf of the NGOs representing the country's "civil society."

And what if the lines are crossed?

The warning deserves to be quoted in full:

Implicitly threatening to give this political instability a push was a list of donors representing a veritable who's who of nefarious US and Western meddlers and color revolutionaries.

Former US State Department official Mike Benz asked the rhetorical question of why USAID would sponsor a 70-NGO consortium that directly threatens the newly elected president and ensures that USAID grantees controlled virtually every facet of how Ukraine could run its own country.

Zelensky, however, would soon have more than the NGOs to worry about.

Set to re-enter the fray was a man with his own red lines.

Through various political intrigues, he managed to wrest informal control of state-owned Centrenergo, Ukraine's most lucrative energy distribution company, and reasserted his influence over Ukrnafta (while this time leaving the headquarters unmolested by armed thugs).

Days later, Gontareva's dacha outside Kiev was firebombed.

Kolomoysky, who had a court-proven history of threatening Gontareva,

was widely suspected to be behind these incidents. Zelensky promised

an investigation. It hardly bears stating that nothing came of it.

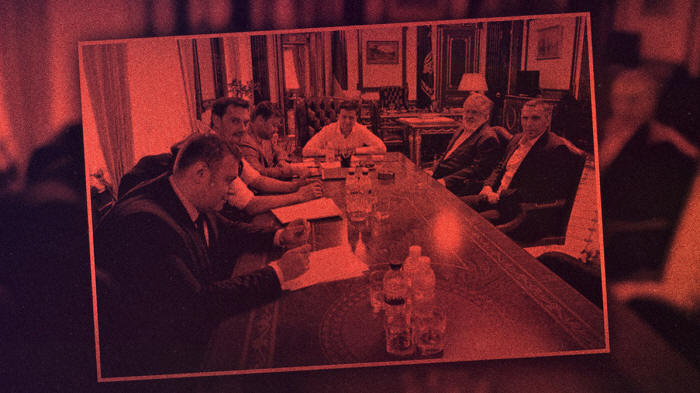

On September 10, he met with Zelensky, his chief of staff, and Kiev's prime minister to discuss,

Investment banker Sergey Fursa bluntly called the photograph accompanying their meeting,

Meanwhile, in December 2019, Zelensky met with Russian President Vladimir Putin, French President Emmanuel Macron, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel in Paris at what was called the Normandy Format for resolving the conflict in Donbass.

However, when it came time to approve the final communiqué, Zelensky got cold feet.

He objected to a critical clause in the document that envisaged a recommendation to the parties to disengage forces along the entire line of contact.

This clause had been endorsed at the level of the foreign ministers and advisers to the heads of state of all parties involved:

The statement ended up being signed with this clause removed, but

from the Russian perspective, it was fatally compromised by

Zelensky's last-minute wavering.

Zelensky's former chief of staff, Bogdan, in a later interview with Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon, admitted that the,

The Ukrainians,

Whether radical nationalists

forced Zelensky's hand is debated,

but either way it was an inflection point.

This was an often underappreciated episode on the path to the

fateful events of February 2022.

It wondered whether what was transpiring was the,

It also identified the biggest question hanging over Zelensky as being his relationship with Igor Kolomoysky.

The IMF was willing to stump up the cash but with conditions attached.

Given the scale of the fraud, it beggars the imagination that such a

step was possible, but Kolomoysky had already made significant

progress toward clawing back his

prized asset and Zelensky seemed

willing to entertain a deal.

Declaring "screw the IMF," he proposed that Kiev default on its loans with the institution.

Instead, the self-proclaimed die-hard European suggested Ukraine embrace Russia.

...he said in late 2019, while blaming the country's tensions with

Moscow on the US "forcing us" to wage a brutal conflict in Donbass.

The solution was to generate enough window-dressing to secure the

money, while simultaneously moving against figures seen as

threatening his benefactor.

Most of the government went with him...

However, the ink had hardly dried from the IMF deal when latter

condition went out the window.

Well-regarded by the IMF, Smolii's departure made a mockery of the conditions Ukraine was expected to fulfill.

A

poll taken at the end of 2020

showed nearly half of Ukrainians were disappointed in his

performance over the past year and 67% believed the country was

heading in the wrong direction.

He called out the "oligarchic class" and named names:

He asked oligarchs directly whether they would be willing to work legally and transparently or whether they intended to maintain their crony networks, monopolies, and pocket parliamentary deputies.

He concluded with a flourish:

These were bold words, but what was the follow-up?

On June 1, 2021, a new 'anti-oligarch bill' was rolled out in the Rada. This measure sought to create an official register of oligarchs. Those classified as such would be banned from donating to political parties and participating in the privatization of state assets.

It was never explained how oligarchs would be forced to sell their media outlets.

The final say on determining who is an oligarch and who should face

what restrictions was left to the National Security and Defense

Council, a body chaired by the president.

According to Emerging Europe,

In November of the same year, the Rada also passed legislation affecting how taxes were administered and calculated.

The measure dealt a hard blow to Kolomoysky rival Rinat Akhmetov and numerous other oligarchs, for example, who were forced to pay increased taxes on iron ore mining.

Inexplicably, however, the Kolomoysky-controlled manganese ore

sector avoided the tax increases faced by the rest of the sector.

But this piecemeal approach to defanging the oligarchs meant some would benefit at the expense of others. But what this really allowed for was a significant increase in the concentration of power in the hands of the president.

And, as we will see, this hardly offered immunity to corruption.

The timing was not self-evident.

The arrest was initially hailed as "a demonstration that there are no untouchables" in Ukraine, and a major step forward in Kiev's fight against entrenched corruption.

Alas, it was the system itself that would prove untouchable.

With a hand dipped surreptitiously in the till of numerous industries, Mindich was both everywhere and nowhere at the same time - or in some cases, in three places at once.

He figures in Ukrainian property registers under at least three names:

These days, he is reportedly hiding out in Austria, although Israel has also been suggested as his bolthole.

He narrowly escaped Ukraine ahead of a National Anti-Corruption

Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) raid on his home on November 10, 2025,

almost certainly having been tipped off.

He was, according to one Ukrainian political heavyweight quoted by Ukrainskaya Pravda, "never a player" and was characterized in terms more apt for a small-time hustler:

He was involved in endeavors such as,

Many Ukrainian business figures later struggled to understand how

someone once seen as a lowly aide could have grown into a figure

with such clout.

As early as 2020, Mindich was regularly seen visiting Zelensky's office and soon thereafter his name began cropping up everywhere.

According to a 2019 interview with Kolomoysky, Mindich - at one point engaged to Kolomoysky's daughter - was the individual who introduced the oligarch to Zelensky in the late 2000s.

In February 2021, Zelensky breached Covid lockdown restrictions to

celebrate his birthday at a private party hosted by Mindich.

As of autumn 2025, he was listed - under his three separate names - as co-owner of at least 15 different Ukrainian companies and organizations, more than half of which were at one time part of Kolomoysky's network.

Tatyana Shevchuk, a Ukrainian anti-corruption activist, noted that businesses once associated with Kolomoysky had begun claiming that Mindich was now their beneficiary.

Kolomoysky's sprawling business empire was never measured by his

registered holdings. What he controlled went far beyond the assets

listed under his name.

Perhaps having learned from his mentor's mistakes, Mindich maintained fewer direct assets and avoided being named in corporate registries, relying instead on political intermediaries.

Nonetheless, Mindich is most prominently associated with state

energy companies - the same sector of which Kolomoysky was once

"daddy."

It was widely reported that the clamp-down came as the agencies were beginning to probe people from Zelensky's circle, possibly targeting Mindich himself.

But perhaps it was more an attempt to diminish the Western influence

and protect those engaging in illicit activities...

It has, however, proven an enormously useful political tool.

A probe into then-President Poroshenko in early 2019 exposed embezzlement and criminal conduct in relation to defense procurement, at the government's highest levels.

Several sources suggest the

revelations contributed to Poroshenko's election loss to Zelensky.

The West has shown a high de facto threshold for tolerating

Ukrainian corruption, but when it reaches levels that could threaten

the stability of the state, pressure is exerted.

The ringleader was identified as none other than Timur Mindich.

Similarly, when Justice Minister Herman Galushchenko and Energy Minister Svetlana Grinchuk were implicated, Zelensky first sought to place them on temporary leave.

Only after a public outcry did he relent and ask for their

resignations.

When NABU investigators raided his residence, Zelensky initially stood by his embattled chief of staff and even dispatched him to carry out negotiations in order to protect him.

It was only after Zelensky's hand was all but forced that he removed Yermak. Mindich's role in government turns out to have been much larger than it appeared at first glance.

According to the SAPO prosecutor,

Anonymous sources told CENSOR.net that Mindich "supervised" Galushchenko.

This apparently extended to direct interference in the ministry's

processes, to the point that Mindich allegedly determined the order

and priority of tasks.

It would be tempting to say that this state of affairs is almost

unheard of if not for its resemblance, at least in its essence, to

what transpired under the ever vigilant eye of Kolomoysky.

The two clearly had a falling out at some point, as an interview from 2022 in which Kolomoysky speaks dismissively about Mindich, calling him "a partner somewhere, but more of a debtor," seems to indicate.

Kolomoysky, no doubt feeling betrayed by Zelensky, seems to have it out for his former protégé as well.

Nevertheless, he has proven a talkative defendant at his recent court hearings in Kiev, so much so that the authorities appear reluctant to haul him in.

Yet Ukraine's elites cultivated these exact attributes with riotous excess, aided and abetted every step of the way by the very Western allies whose system Kiev ostensibly sought to emulate.

Only when corruption took on such grotesque dimensions that it

threatened Ukraine as a functioning bludgeon against Russia was it

addressed. All manner of malfeasance was tolerated and tacitly

encouraged until an inflection point was reached.

If this were a film, it would end with the one truly patriotic act in Igor Kolomoysky's long and disreputable life at the nexus of Ukrainian politics and business being to detonate the very system that he was so central to building.

Additional information from

The New York Times.

|