|

The accuracy of the story

is not yet clear, but for Britain, leaving the European Union and

building a closer trade relationship with the United States, and

therefore with North America, follows geopolitical logic.

One force driving British imperialism was the need to develop markets and sources outside Europe so as not to become excessively dependent on Europe.

The Royal Navy was designed both to protect Britain from continental powers and, in time of war, to blockade hostile European powers without being excessively drawn into combat on the Continent.

The British hesitated for a long time before agreeing to join the European Community and the powers on the Continent (particularly the French) hesitated for a long time before admitting them.

The British were

instrumental in creating the "Outer

Seven" bloc of nations on the Continent's periphery as an

alternative to what would eventually become the European Union.

Had he been able to impose a stable system, dominated by Paris, on the Continent, the economic and military force he could have mustered would have overwhelmed Britain's naval defenses in the not-too-long run and compelled Britain to accommodate itself to French hegemony.

In this hegemony, it

would have found itself at a perpetual disadvantage (as would other

nations) as France tilted the economic system in its favor. It

therefore joined the anti-Napoleonic alliance and,

after Waterloo, cautiously withdrew

from the Continent and focused on its empire.

The point that must be borne in mind was that membership in a European bloc ran counter to historic British views of Europe.

The British fear was that

the constraints imposed by any European alliance would inevitably

tilt the economic system against Britain and threaten its

sovereignty.

It had also decisively brought another nation into the dynamic:

At the end of World War I, the United States had the same perspective as the British.

The U.S. wanted the same thing Britain had wanted:

This was the intent of the Treaty of Versailles, which blocked France from dismembering Germany and achieving Napoleon's goal of dominating the Continent.

Versailles also set the

stage for World War II, once Germany had reorganized itself.

The conflict also reversed the relationship between the United States and Britain.

After World War I, the U.S. maintained a set of war scenarios that included War Plan Red, which was based on a potential British invasion from Canada.

Far-fetched as this might seem now,

In 1920, the mutual suspicion continued; indeed, when lend-lease was enacted, the U.S. lent ships to Britain - but Britain leased almost all of its bases in the Western Hemisphere to the U.S., ending centuries of domination of the Atlantic and a perpetual threat to the United States.

In 1956, the U.S. blocked Britain (and France and Israel) from retaking the Suez Canal.

President Franklin

Roosevelt had made it clear that the U.S. was fighting to defeat

Germany and not to save the British Empire. The two countries were

imperfectly aligned, to say the least.

In a way,

But the U.S. focus was not European integration.

Washington was worried about the Soviets and wanted a prosperous, united Europe that could field a military. The British were uneasy about integration, and the French were cautious about Britain.

The old tensions did not dissolve. Nor did German weakness.

The U.S. needed Germany to recover, since Germany would be the battleground of any future war. And so it did, and over time an integrated Europe became a German-dominated Europe, benign militarily, aggressive economically.

Britain's strategy was to maintain its distance from Europe by building a special military and intelligence relationship with the United States, while cautiously dipping its toes into European integration.

In other words, the

British managed to maintain a European balance of power while at the

same time creating a balance between Europe and the United States,

using the space this opened to pursue their own interests.

For Britain, the EU delivered a degree of prosperity at the loss of a degree of sovereignty.

This arrangement could work if it was meticulously balanced. But the EU was not a flexible entity in which Britain could work its historic subtlety.

This split Britain down the middle between,

The damage to the United

Kingdom's stability was substantial, the fear of declining

prosperity real.

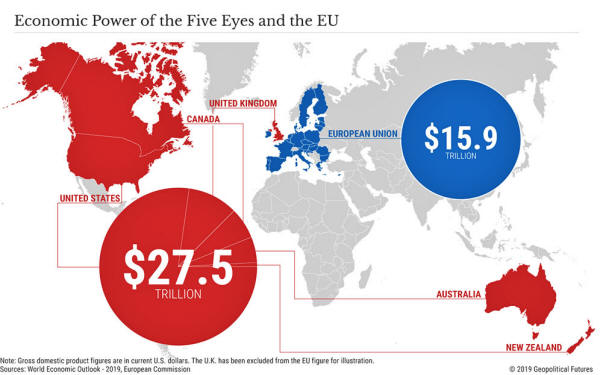

Britain's military and intelligence relationships with its former settler colonies,

...were an important dimension of its global vision.

They were also foundational to the American alliance system, with all five countries participating in the "Five Eyes" intelligence-sharing group and maintaining intimate military cooperation.

Canada and Australia have

significant trade agreements with the United States, and New Zealand

is negotiating one.

Britain already conducts

substantial trade with all four nations, which requires a degree of

integration, but it's limited to market access on favorable terms.

On the other hand,

The weight of this group in world affairs would be massive.

But nowhere would it be as fraught with tension as in Britain.

A trade agreement with

the United States is the logical and even inevitable step, but one

with long-term significance...

|