|

by Tyler Durden

May 27, 2016

from

ZeroHedge Website

In a stunning reversal for an organization that rests at the bedrock

of the modern "neoliberal" (a term the IMF itself uses generously),

aka

capitalist system, overnight IMF authors Jonathan D.

Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri issued

a research paper titled "Neoliberalism

- Oversold?" whose theme is

a stunning one:

it accuses neoliberalism, and its

immediate offshoot, globalization and "financial openness", for

causing not only inequality, but also making capital markets

unstable.

To wit:

There are aspects of the neoliberal

agenda that have not delivered as expected.

Our assessment of

the agenda is confined to the effects of two policies:

-

removing restrictions on the

movement of capital across a country's borders

(so-called capital account liberalization)

-

fiscal consolidation,

sometimes called "austerity," which is shorthand for

policies to reduce fiscal deficits and debt levels

An assessment of these specific

policies (rather than the broad neoliberal agenda) reaches three

disquieting conclusions:

-

The benefits in terms of

increased growth seem fairly difficult to establish when

looking at a broad group of countries.

-

The costs in terms of

increased inequality are prominent. Such costs epitomize

the trade-off between the growth and equity effects of

some aspects of the neoliberal agenda.

-

Increased inequality in turn

hurts the level and sustainability of growth. Even if

growth is the sole or main purpose of the neoliberal

agenda, advocates of that agenda still need to pay

attention to the distributional effects.

Wait... you mean that

the IMF becoming,

gasp, Marxist?

Did last summer's dramatic interaction

with Greece and its brief but memorable former Marxist finance

minister, Yanis Varoufakis, leave such a prominent mark on

the IMF's collective subconsciousness, that it is now overly

rejecting the tenets on which the IMF was originally founded?

Let's read on for the answer...

Here is a very notable segment on "globalization" aka financial

openness:

In addition to raising the odds of a crash, financial openness has

distributional effects, appreciably raising inequality. Moreover,

the effects of openness on inequality are much higher when a crash

ensues.

It gets better:

The mounting evidence on the high

cost-to-benefit

The mounting evidence on the high

cost-to-benefit ratio of capital account openness, particularly

with respect to short-term flows, led the IMF's former First

Deputy Managing Director, Stanley Fischer, now the vice chair of

the U.S. Federal Reserve Board, to exclaim recently:

"What useful purpose is served

by short-term international capital flows?"

Among policymakers today, there is

increased acceptance of controls to limit short-term debt flows

that are viewed as likely to lead to - or compound - a financial

crisis.

While not the only tool available -

exchange rate and financial policies can also help - capital

controls are a viable, and sometimes the only, option when the

source of an unsustainable credit boom is direct borrowing from

abroad.

The IMF then goes full-Magic Money Tree

and reverts back to a mode first observed several years ago when it

said that not only is austerity bad, but that unlimited debt

issuance is probably good.

Markets generally attach very low

probabilities of a debt crisis to countries that have a strong

record of being fiscally responsible.

Such a track record gives

them latitude to decide not to raise taxes or cut productive

spending when the debt level is high.

And for countries with a strong

track record, the benefit of debt reduction, in terms of

insurance against a future fiscal crisis, turns out to be

remarkably small, even at very high levels of debt to GDP.

For example, moving from a debt

ratio of 120 percent of GDP to 100 percent of GDP over a few

years buys the country very little in terms of reduced crisis

risk.

But even if the insurance benefit is small, it may still be

worth incurring if the cost is sufficiently low. It turns out,

however, that the cost could be large - much larger than the

benefit.

The reason is that, to get to a

lower debt level, taxes that distort economic behavior need to

be raised temporarily or productive spending needs to be cut -

or both. The costs of the tax increases or expenditure cuts

required to bring down the debt may be much larger than the

reduced crisis risk engendered by the lower debt.

This is not to deny that high debt

is bad for growth and welfare. It is...

But the key point is that the

welfare cost from the higher debt (the so-called 'burden of the

debt') is one that has already been incurred and cannot be

recovered; it is a sunk cost.

Faced with a choice between living

with the higher debt - allowing the debt ratio to decline

organically through growth - or deliberately running budgetary

surpluses to reduce the debt, governments with ample fiscal

space will do better by living with the debt.

Of course, what both the IMF and

the

Magic Money Tree lunatics fail to grasp, is that the only reason

debt interest hasn't exploded in a world that has never had more

debt (a process that inevitably ends in war) is thanks to central

bank monetization of said debt, and third party investors

front-running said central banks.

Let's revert to the "low costs of debt"

if and when runaway inflation forces central banks to reverse what

has been a 30+ year process that started with the great moderation

and will end either with helicopter money (and thus hyperinflation)

or central banks owning every single assets (and thus the death of

capitalism.

But back to the IMF's rant, just in case the IMF's dramatic U-turn

on its support for a neoliberal agenda was not clear, here is

another reiteration:

In sum, the benefits of some

policies that are an important part of the neoliberal agenda

appear to have been somewhat overplayed. In the case of

financial openness, some capital flows, such as foreign direct

investment, do appear to confer the benefits claimed for them.

But for others, particularly

short-term capital flows, the benefits to growth are difficult

to reap, whereas the risks, in terms of greater volatility and

increased risk of crisis, loom large.

In the case of fiscal consolidation,

the short-run costs in terms of lower output and welfare and

higher unemployment have been underplayed, and the desirability

for countries with ample fiscal space of simply living with high

debt and allowing debt ratios to decline organically through

growth is underappreciated.

The IMF's punch-line:

[S]ince both openness and austerity

are associated with increasing income inequality, this

distributional effect sets up an adverse feedback loop.

The increase in inequality

engendered by financial openness and austerity might itself

undercut growth, the very thing that the neoliberal agenda is

intent on boosting.

There is now strong evidence that

inequality can significantly lower both the level and the

durability of growth.

And here is the IMF doing the

unthinkable, and waving to Marx:

The evidence of the economic damage

from inequality suggests that policymakers should be more open

to redistribution than they are.

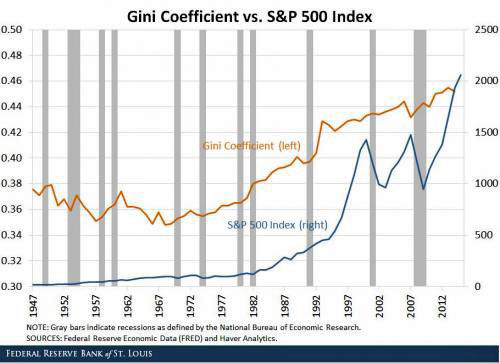

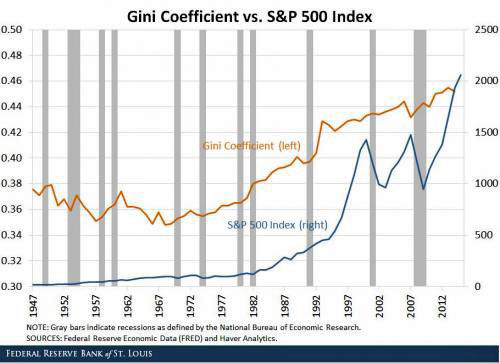

As a reminder, this is taking place just

days after the St. Louis Fed admitted the Federal Reserve itself is,

indirectly, a primary reason for the current record wealth

inequality thanks with its focus on the "wealth effect" and boosting

asset prices.

What is the conclusion from all this?

Perhaps that the push for

global wealth redistribution, and an end to conventional capitalism,

is in the works.

How this transition takes place is unknown:

whether by government

decree, by regime change, by a - paradoxically - global government

(one in which the IMF would be delighted to administer global

monetary policy) to rein in globalization, or simplest of all, by

helicopter money, is still unclear.

Whatever it is, something is coming, because for a stunning paper

such as "Neoliberalism

- Oversold?" to be published, it certainly had to be vetted

not only at all executive levels of the IMF, but was surely

preapproved by all legacy financial institutions.

And that should be the basis for great concern...

IMF Blames

Neoliberalism

...for Low Growth

and Increased Inequality

by Dan Wright

01 June 2016

from

ShadowProof Website

Screen shot of IMF

report on neoliberalism

showing Chile stock

exchange.

A new paper from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a pillar of

neoliberal globalization and neo-colonial domination of the

developing world, takes a rhetorical shot at the very system it

perpetuates.

The paper, titled "Neoliberalism

- Oversold?," is published

in the June 2016 issue of the IMF's official journal, "Finance &

Development," and starts its analysis of the spread of neoliberalism

with post-1973 coup Chile where the military junta led by General

Augusto Pinochet adopted an economic program crafted by U.S.

economist Milton Friedman.

As the paper notes, in 1982, Friedman

called Chile an "economic miracle" and the policies Chile

implemented that had been proposed by Friedman and the

Chicago Boys became a blueprint for

what would popularly become known as neoliberalism.

The IMF notes two main planks of

neoliberalism that went global after Chile:

"The first is increased competition

- achieved through deregulation and the opening up of domestic

markets, including financial markets, to foreign competition.

The second is a smaller role for the

state, achieved through privatization and limits on the ability

of governments to run fiscal deficits and accumulate debt."

While the IMF celebrates the

globalization of neoliberal policies overall (how could they not

given their institutional role), they do concede that there are,

"aspects of the neoliberal agenda

that have not delivered as expected."

Specifically, the IMF paper cites

removing capital controls and imposing austerity as particularly

problematic for growth and wealth distribution, leading them to

conclude:

-

The benefits in terms of

increased growth seem fairly difficult to establish when

looking at a broad group of countries.

-

The costs in terms of increased

inequality are prominent. Such costs epitomize the trade-off

between the growth and equity effects of some aspects of the

neoliberal agenda.

-

Increased inequality in turn

hurts the level and sustainability of growth. Even if growth

is the sole or main purpose of the neoliberal agenda,

advocates of that agenda still need to pay attention to the

distributional effects.

In other words, austerity and

unrestricted capital movements do not improve economic growth but do

exacerbate inequality.

Though obvious to most, such an admission

from the IMF is noteworthy, as is the alternative perspective in the

paper's conclusion.

Rather than double down on deregulation

and embrace Friedman's vision of unrestricted capitalism, the paper

sides with economist Joseph Stiglitz on balancing market forces with

a stronger regulatory state.

If the IMF genuinely adopted such a view

then many of the loan packages given to countries around the world

would have to change considerably.

Currently, states accepting IMF loans

are typically required to deregulate their economy, privatize public

resources, and open themselves up to foreign capital flowing in and

out - the consequences of which have been continual financial and

economic crisis.

Under this new understanding the IMF

should, in theory, ask for more regulations, more stimulative state

spending, and tighter controls on capital flows.

Then again, if the IMF did take such an

approach, it would face intense resistance from its most prominent

backers in the corporate and

banking sectors that have benefited the

most from privatizing public assets and unrestrained financial

speculation.

|