|

by April McCarthy

February 3, 2014

from

PreventDisease Website

Spanish version

|

April McCarthy is a

community journalist playing an active role reporting

and analyzing world events to advance our health and

eco-friendly initiatives. |

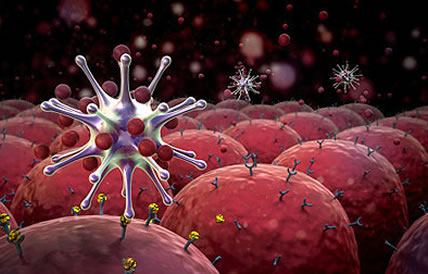

It takes no more than 100 seconds for the body's immune cells to

identify and kill a cancer cell. Immune cells undergo ‘spontaneous’

changes on a daily basis that could lead to cancers if not for the

diligent surveillance of our immune system, Melbourne scientists

have found.

A research team from the

Walter and Eliza Hall Institute found

that the immune system was responsible for eliminating

potentially cancerous immune B cells in their early stages,

before they developed into B-cell lymphomas (also known as

non-Hodgkin's lymphomas).

The results of the study were

published today in the journal

Nature Medicine.

The immune system's basic task is to recognize "self" (the body's

own cells) and "nonself" (an antigen - a virus, fungus, bacterium,

or any piece of foreign tissue, as well as some toxins). To deal

with nonself or antigens, the system manufactures specialized cells

- white blood cells - to recognize infiltrators and eliminate them.

We all come into the world with some innate immunity.

As we interact with our environment, the

immune system becomes more adept at protecting us. This is called

acquired immunity.

Many mature white blood cells are highly specialized. The so-called

T lymphocytes (T stands for thymus-derived) have various functions,

among them switching on various aspects of the immune response, and

then (equally important) switching them off. Another lymphocyte, the

B cell, manufactures antibodies.

A larger kind of white cell, the

scavenger called the phagocyte (most notably the macrophage), eats

up all sorts of debris in tissue and the bloodstream, and alerts

certain T cells to the presence of antigens.

''The T-cells basically detect the

enemy and then throw grenades at the cancer cell until it blows

up,'' said immunologist Misty Jenkins from the Peter MacCallum

Cancer Centre.

T-cells are a type of white blood cell

that are key to the body's immune response.

Normally when a T-cell kills the target,

the only way you would know that the target has been hit or killed

is when it physically starts to die.

However the B-cells bind to a specific antigen and antibodies

against these antigens, thus performing the role of

antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and to develop into memory B

cells after activation by antigen interaction.

This immune surveillance accounts for what researchers at the

institute call the 'surprising rarity' of B-cell lymphomas in the

population, given how often these spontaneous changes occur.

The discovery could lead to the

development of an early-warning test that identifies patients at

high risk of developing B-cell lymphomas, enabling proactive

treatment to prevent tumors from growing.

All B-cells, whether healthy or cancerous, have on their surfaces a

proteins. To treat patients with the disease, the researchers need

to find ways to reprogram their T-cells to find the proteins and

attack B-cells carrying it.

Dr Axel Kallies, Associate Professor David Tarlinton,

Dr Stephen Nutt and colleagues made the discovery while

investigating the development of B-cell lymphomas.

Dr Kallies said the discovery provided an answer to why B-cell

lymphomas occur in the population less frequently than expected.

"Each and every one of us has

spontaneous mutations in our immune B cells that occur as a

result of their normal function," Dr Kallies said. "It is then

somewhat of a paradox that B cell lymphoma is not more common in

the population.

"Our finding that immune surveillance by T cells enables early

detection and elimination of these cancerous and pre-cancerous

cells provides an answer to this puzzle, and proves that immune

surveillance is essential to preventing the development of this

blood cancer."

B-cell lymphoma is the most common blood

cancer in Australia, with approximately 2800 people diagnosed each

year and patients with a weakened immune system are at a higher risk

of developing the disease.

The research team made the discovery while investigating how B cells

change when lymphoma develops.

"As part of the research, we

'disabled' the T cells to suppress the immune system and, to our

surprise, found that lymphoma developed in a matter of weeks,

where it would normally take years," Dr Kallies said.

"It seems that our immune system is

better equipped than we imagined to identify and eliminate

cancerous B cells, a process that is driven by the immune T

cells in our body."

Associate Professor Tarlinton said the

research would enable scientists to identify pre-cancerous cells in

the initial stages of their development, enabling early intervention

for patients at risk of developing B-cell lymphoma.

"In the majority of patients, the

first sign that something is wrong is finding an established

tumour, which in many cases is difficult to treat" Associate

Professor Tarlinton said.

"Now that we know B-cell lymphoma is

suppressed by the immune system, we could use this information

to develop a diagnostic test that identifies people in early

stages of this disease, before tumors develop and they progress

to cancer. There are already therapies that could remove these

'aberrant' B cells in at-risk patients, so once a test is

developed it can be rapidly moved towards clinical use."

|