|

by D.M. Murdock/Acharya S December 2010 from TruthBeKnown Website

Over the decades I have been researching the subject of the origins of Christianity, as well as religion and mythology in general, I have come across many astonishing facts that I have passionately worked to bring to light for the enjoyment of others.

Along with this work has been the

development of a history for what is called "mythicism," which in

this context specifically refers to the study of various biblical

characters, such as Jesus Christ, as mythical and not historical

figures.

One of the juiciest tidbits I have ever

uncovered on this quest is the evidence that at least a couple of

the American Founding Fathers appear to have entertained the ideas

of Jesus mythicism, although this contention seems to have been

omitted from the historical record as much as is possible, for

obvious reasons, perhaps. "Some of the most famous early Americans may have considered Jesus Christ to have been a myth."

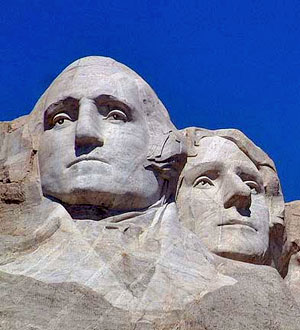

Washington and Jefferson immortalized at Mt. Rushmore

It is a fascinating concept that some of the most famous early Americans may have considered Jesus Christ to have been a myth, but there are intriguing indications that it is true, at least in part or at certain times.

In this regard appears the following

astounding quote, which suggests that first and third American

Presidents George Washington (1732-1799) and Thomas Jefferson

(1743-1826) were closet mythicists!

The pertinent part of this eye-popping

quote bears repeating: "Washington even was glad to have Volney as his guest at Mount Vernon, and Jefferson occupied his Sundays at Montecello in writing letters to Paine..., in favor of the probabilities that Christ and his twelve apostles were only personifications

of the sun and the twelve signs of the

zodiac." The author of these revealing contentions refers to Count Volney, a famous French traveler, philosopher, writer and "Jesus mythicist" of the 18th to 19th centuries, as well as to the Anglo-American philosopher, writer and "Lost Founder" Thomas Paine (1737-1809).

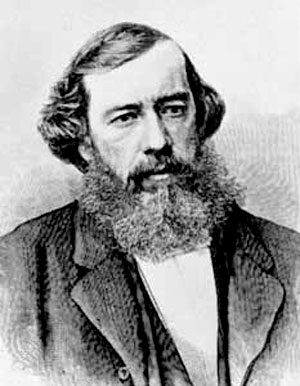

Rev. Dr. Moncure

Daniel Conway

Moncure Daniel Conway Library of Congress

This article about the State of Virginia was republished in Littell's Living Age (no. 1088/8 April, 1865; p. 12), edited by Eliakim Littell.

The author is not identified in either place, but the Wellesley Index to Victorian Publications (173) does identify him as Rev. Dr. Moncure Daniel Conway (1832-1907), a Harvard Divinity School graduate, minister, prominent abolitionist and friend of Charles Darwin, among other luminaries.

Dr. Conway was also a well-known and

foremost expert on Thomas Paine, having pored over the latter's

writings and correspondence, and composed a two-volume, oft-cited

biography about him.

Under such circumstances, it is

difficult to believe that this respectable individual was behaving

mendaciously, and with the indications revealed here, we may

logically conclude that Conway did not fabricate these letters or

engage in "rhetoric" concerning their content.

The implication here is that the

mysterious and controversial Count had been introduced to American

society by none other than George Washington himself.

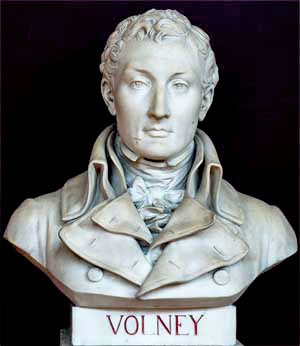

Volney, Dupuis and

Napoleon

Like his fellow French mythographer,

college professor and early mythicist writer Charles Dupuis

(1742-1809), Volney was also a tutor of French leader Napoleon

Bonaparte (1769-1821), who made him a senator and a count.

Charles Dupuis French mythographer

Unearthing fascinating facts concerning ancient religion and mythology, one of the academician Dupuis's major views in his multivolume work Origine de tous les cultes ou religion universelle (1795) or Origin of All Religious Worship can be summarized as follows:

In this same regard, Volney remarked:

In The Ruins, Volney's section on Jesus (172) is entitled:

Thus, Dupuis and Volney's thesis was

that Christ was a mythical figure based on the sun. "It is quite a big question, whether Jesus Christ has ever lived."

Christopher Martin Wieland and Napoleon Bonaparte

So influential were Dupuis and Volney that in 1808 at Weimar, Germany, Napoleon remarked into the ear of a German writer, Christopher Martin Wieland (1733-1813):

In this regard, it is contended that

Napoleon's "Commission" to Egypt (1798-1801) was inspired by

Dupuis's work, with the desire to find evidence of the religion and

mythology that influenced Christianity leading to the discovery of

the Rosetta Stone. (Knight, 679)

We are further told that Dupuis informed

Paine and Chancellor Livingston of Napoleon's remarks. (Theoanthr.,

150)

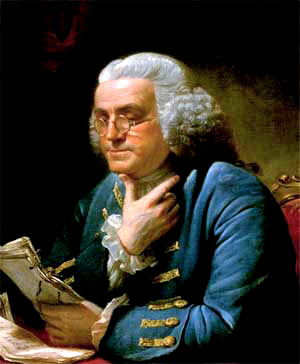

Volney and Franklin

Benjamin Franklin oil portrait by David Martin, 1767 White House

Unsurprisingly considering the exalted

company he kept, but highly interesting nonetheless, Volney was also

friends with American Founding Father Dr. Benjamin Franklin

(1706-1790), a known irreverent rabblerouser whom the Count

encountered in France:

In Volney's subsequent correspondence

with Franklin (Wilson, 306), the two evidently discussed philosophy,

but Volney's book on mythicism was not published until one year

after Franklin's death.

"Lighthouses are more useful than

churches." Baptized a Puritan, Franklin adopted Deism as a young man, declaring in his autobiography,

Although he was a spiritual theist who believed in "the Deity" and who encouraged humanity to worship and pray, Franklin himself did not subscribe to organized religion, once remarking, "Lighthouses are more useful than churches."

In consideration of his friendship with

Volney and Paine, et al., one wonders whether or not Franklin too

was at the very least a "rational Unitarian," as appears to have

been somewhat common among Deists.

Voltaire and

Bolingbroke

(Linton, x) Born François-Marie Arouet,

the pseudonymous Voltaire himself was certainly aware of the

Christ-myth thesis, having once written (273): "I saw some disciples of Bolingbroke...,

who denied the existence of a Jesus..."

François-Marie Arouet, aka Voltaire oil by Catherine Lusurier Musée national du Château et des Trianons

Voltaire is referring to the English philosopher Henry Saint John, the Viscount Bolingbroke (1678-1751).

In identifying Bolingbroke's Deist disciples as Jesus mythicists, Voltaire has traced back this school of thought to before the time of Dupuis. Certainly, these Deists were likewise not the first mythicists.

Despite knowing about the mythicist

position, Voltaire evidently retained his perception of a historical

Jesus in order to run down the latter's character, which he could

not do if Christ were a myth. (Bietenholz, 325)

The word comes from the Latin "deus,"

which means "God" and which was previously used interchangeably with

the Greek term "theos," likewise meaning "God." "A number of the Founding Fathers had been exposed to ancient mythology

and were disinclined to believe in the

miracles of the Bible, including parts of the gospel story." A number of the Founding Fathers were classically educated and knew much about the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, and it is claimed that, like Franklin, several others were Deists, rather than orthodox Christians.

Thus, they had been exposed to ancient mythology and were disinclined to believe in the miracles of the Bible, including parts of the gospel story.

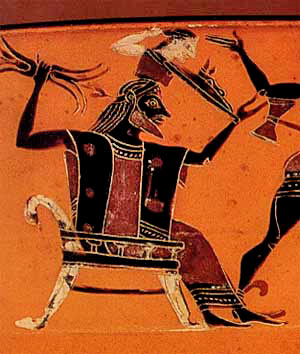

Athena springs from the mind of Zeus Phrynos Painter, c. 560-550 BCE University of Haifa Library

It appears that some of these individuals were also sympathetic to the idea of Unitarianism as well, the "nontrinitarian" ideology that denies the Triune nature of God in favor of a divine Unity.

During this period in history,

Unitarians espoused what is called "rationalist unitarianism," which

essentially rejects the miracles and mythical motifs of

Christianity, such as the virgin birth, as reflected in Jefferson's

quote about Minerva (Athena) and Jupiter (Zeus).

Indeed, these ideas all seem to have

coalesced at various times in the views of certain Founding Fathers,

some of whom were apparently intrigued by mythicism, such as

Washington, Jefferson, Paine and possibly others acquainted with

Volney.

Volney and Washington

Bust of Constantin-François Volney Salle du serment du jeu de paume, Versailles photo by Philippe Dessante

In 1795, Volney traveled to the United States with the intention of settling in America, and was welcomed by President George Washington personally.

At his meeting with Washington, Volney

recounted to the amazement of the Americans the exact moves of

Napoleon's military campaigns as they were happening, proving that

he knew the French leader well. (Wilson, 306)

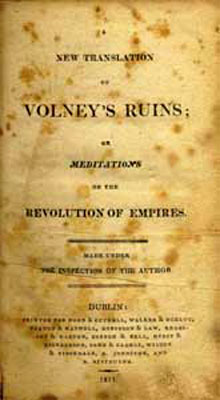

The presence of these letters in his library demonstrates that Washington was aware of this controversy, which significantly swirled around Volney's mythicism, as concerned his,

Moreover, in the history section of the

Athenaeum collection we discover that Washington also possessed a

copy of Volney's The Ruins of Empires, in which the controversial

thesis of Jesus mythicism is laid plain. (Griffin, 515) "Washington possessed a copy of Volney's The Ruins of Empires,

in which the controversial thesis of

Jesus mythicism is laid plain." In consideration of these facts, it is probable that Washington was cognizant of Volney's arguments in favor of mythicism, even if he did not embrace them fully or publicly.

Jefferson did, however, label himself a Unitarian, and he was so skeptical of many parts of the gospel story that he took a razor and literally cut out these unbelievable miraculous, mystical and magical scriptures, leaving a much thinner book.

This "Jefferson Bible," as it is known, is based on Jesus's "principles of a pure deism," a task that the American statesman had originally asked Rev. Priestley to do.

In his

letter to Priestley of April 9, 1803, Jefferson mentions

"Pythagoras, Epicurus, Epictetus, Socrates, Cicero, Seneca, Antoninus" and speaks of Jesus as historical figure, albeit one who

has been evemeristically mythologized. (Jefferson 1854, 475-476)

Joseph Priestley Rembrandt Peale, 1801

Priestly was an influential Unitarian minister, a denomination that in Jefferson's time stripped away the miraculous and focused on Jesus the compassionate man, the same position Jefferson took in his Bible.

The minister, who had assailed Volney over his mythicism, was convinced not only that Jesus had existed as a historical figure but also that he had essentially been a Unitarian, like Priestley himself, who set out to prove this premise in his book about Christ.

During his sojourn in America between 1795 and 1798, Volney visited Jefferson at Monticello. (Leopold, 4)

In this regard, in his letter of June 12, 1796 to then-Colonel James Monroe (1758-1831), fifth President of the United States and author of the Monroe Doctrine, Jefferson casually remarks,

Volney needs no introduction to Monroe,

and it is obvious that he is well known among the American elite of

the time. A week later (6/17/1796), Jefferson wrote to the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), who had been a general under Washington in the Revolutionary War and whose whereabouts Jefferson had learned from "M. Volney, now with me" (still). (Jefferson 1829, 338)

One wonders what engrossing

conversations the two may have engaged in at that time.

John Adams Samuel Finley Breese Morse, 1816

Despite Volney having friends in such high places, in 1798 second American President John Adams (1735-1826), evidently influenced by Priestley and others, was able to drive the "infidel" Volney from America, allegedly out of,

In view of such treatment of

nonbelievers, it may be understood why interest in mythicism has not

been overtly declared by the erudite and elite such as are discussed

here.

Further demonstrating his knowledge of

Volney's work, in 1815 Jefferson sold as part of his collection to

Congress a copy of the English translation of Volney's The Ruins,

published in 1796 - the same year Volney visited Jefferson at

Monticello. "[Volney's] ideas are similar to those represented in Jefferson's writing of the Declaration of Independence

and the statute of Virginia for

religious freedom."

Volney's Ruins of Empires 1811

Speaking of the philosophical views in Volney's book, the Library of Congress (2/24/2000) remarks,

Like Washington, Jefferson also had in his collection the commentary by Priestley on Volney's mythicism, revealing he also knew about that debate, which might explain any evident reticence on his part about jumping into this intellectual fray, an apparent factor in the introduction of the "alien bills" Adams had used to expel the French mythicist.

In consideration of the hostility from

the highest office of the land, it is understandable if these

gentlemen did not commit to writing much of their personal

conversations about religion.

Thomas Paine oil by Auguste Millière (1880) after an engraving by William Sharp after a portrait by George Romney (1792)

As early as 1793, Jefferson was aware that Paine was critical of the gospel story, as in a letter of that year to Jefferson, U.S. Minister to France Gouverneur Morris informs him that Paine is in prison,

The pamphlet to which Morris refers, the first part of The Age of Reason, is a deistic tract that takes a typical evemerist position of Jesus being a "virtuous and amiable man" (Paine 1852, 14).

In that same writing, Paine refers

repeatedly to "Christian mythology" and "Christian mythologists."

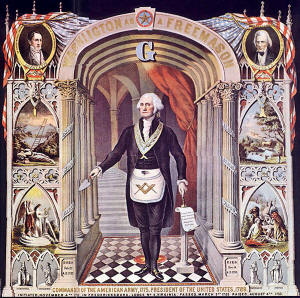

(E.g., Paine 1852, 12) "The Christian religion and Masonry have one and the same common origin,

both are derived from the worship of the

sun." As he had done in his letter of 1806 to Andrew A. Dean (quoted above), in his "Origins of Free-Masonry" Paine likewise equated Jesus with the sun:

George Washington as Freemason

In this regard, George Washington himself was a Mason (Mulsow, 193), as was Benjamin Franklin (Popkin, 50).

There is no official record of Thomas Jefferson being a Mason, but he was surrounded by Masons in his family and as business and political associates, and he attended a number of Masonic meetings and ceremonies at various lodges. (Beless)

It is therefore likely that all three men were familiar with the

doctrine outlined by Paine.

As American historian Dr. Bruce Kuklick writes (xxiii),

In this same vein, when in 1802 Paine

went to publish his third part of Age of Reason along with a

response to a prominent churchman who had assailed his work,

Jefferson requested him not to do so. (Morais, 126)

Any fears about censure - or worse - would have been well founded, however, as was discovered a couple of decades later, when popular English minister Robert Taylor was imprisoned for saying essentially the same thing, i.e., for being a mythicist.

Rev. Dr. Robert Taylor (1784-1844)

One of Dupuis and Volney's later devotees was Rev. Robert Taylor, author of 'The Diegesis', whose mistreatment under England's "blasphemy" laws badly frightened the budding evolutionist and Conway friend Dr. Charles Darwin as to his own potential fate.

Taylor was notoriously arrested, tried and convicted for publicly calling into question the veracity of the Bible and Christian tradition, preaching from the pulpit that Christ was a mythical figure.

He served two prison sentences in the late 1820s and early 1830s for a total of three years, during which time he defiantly wrote two mythicist works, The Syntagma and The Diegesis.

If Darwin was aware of Taylor's fate, he

was likely also knowledgeable about what the minister had been

preaching: To wit, Jesus Christ was a mythical not historical

figure, based on pre-Christian solar mythology. "Such ill treatment may indicate why so little mythicism has made it into the public view, with questioners of the 'historical Jesus' treated as pariahs

in both the public at large and the

hallowed halls of academia." Such ill treatment may indicate why so little mythicism has made it into the public view, even to this day, with questioners of the evidence for the "historical Jesus" and propounders of mythical parallels treated as pariahs in both the public at large and the hallowed halls of academia.

However, as we can see from this fascinating story, there is more to the picture than meets the eye, and the question of Jesus's historicity has been on the minds of many of the greatest and most influential thinkers of all time.

Indeed, perceiving Jesus as the "Sun of

Righteousness" was based on the scripture at

Malachi 4:2, the

biblical book immediately preceding the Gospel of Matthew, and this

tradition of solar imagery within Christianity has continued

abundantly to the present day.

As theologian Rev. Dr. Tim Hegedus remarks in Early Christianity and Ancient Astrology (343):

Miniature zodiac, with Helios (Sun) as Christ, surrounded by the apostles, corresponding to the zodiacal signs

813-820 AD/CE;

Vaticanus graecus 1291

This correlation continued throughout

early Christianity into the Middle Ages, as evidenced by imagery of

Jesus as the central sun surrounded by his 12 as the zodiac, as

discussed by famed churchman the Venerable Bede, for one, in the

seventh century:

It is also obvious that the public expression of such mythicism, whether verbal or written, could bring down the persecutory wrath of the reigning authorities, which explains why this amazing and important history is not more widely known. Until today...

|