|

Recently, Rosslyn Chapel, just to the South of Edinburgh, has been described as Britain's answer to Rennes-le-Château.

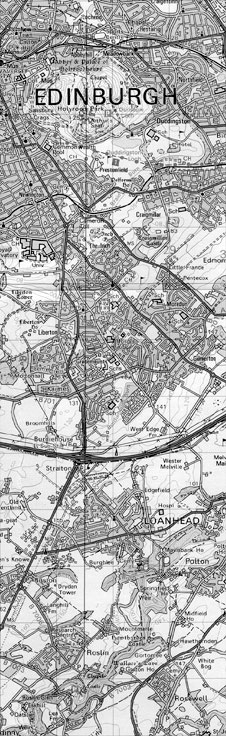

That small village is the focus of a decades-long treasure chase, after the local priest, Berenger Sauniere, was believed to have known a secret, possibly the location of an important treasure. Two chapels, but there the connection seems to end; Rosslyn does not have an enigmatic priest, and fortunately it is much more accessible than Rennes-le-Chateau, situated just outside Edinburgh's City Bypass.

But since a decade, a series of authors have claimed that Rosslyn Chapel contains a secret.

What secret?

Some have grandiosely claimed it is the Grail, others the Head of Jesus, others secret scrolls detailing the life of Jesus. If we take all these theories as a group, it seems that Rosslyn Chapel acts as a magnet for all important treasures; perhaps there is even a bus service between Rennes-le-Chateau and Rosslyn Chapel operated by the Illuminati shuttling the various treasures back and forth.

All kidding aside, Rosslyn Chapel was thrown into the mystery of Rennes-le-Chateau in the 1980s, by Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln. The connection was based on how the last grandmaster of the Priory of Sion, who claim to guard the secret of Rennes-le-Chateau, was named Pierre Plantard. But he added "de St Clair" to that name, and hence made the connections with the "Sinclairs", the modern spelling from the medieval "St Clair" of Rosslyn Chapel.

The lid was opened: as the Templars had their Scottish headquarters near to Rosslyn Chapel, at Ballantrodoch (now renamed Temple), the trio of authors wondered whether the Templars, upon their dissolution went to Scotland - some Masonic legends from the 19th Century claimed as much - and hid their secrets in Rosslyn Chapel.

In the 15th Century, William St Clair built Rosslyn Chapel and by the early 18th Century, copying the example of the English freemasonry, Scottish freemasonry was "made public", with William St Clair, namesake and descendent from the chapel builder, the first Grandmaster. However, the Scots had to outdo the English, and hence claimed that even though they had not gone public first, their Masonic institution had been going for several centuries, and that the Sinclair were the "hereditary grandmasters".

So were the St Clairs the missing link

between the Templars and the Masons? The answer seemed to be a

straightforward "yes".

First of all, Plantard taking the name St Clair is nice for him, but there is no evidence at all - and many have looked - that he is connected with Rosslyn. There is no connection between the Priory of Sion and Rosslyn - none of the Priory documents claim such a connection; they only people claiming such a connection are British-based authors who speculate on whether such a connection might exist or not.

And so far, none have found any evidence. Though it is possible Templars hid in Scotland, Ballontrodoch and Rosslyn Chapel were not a safe-haven for the Templars. Falling under English rule at the time, the knights of Ballontrodoch were arrested. In the ensuing trials, the Sinclairs actually testified against these Templars.

In 1736, when Scottish masonry went

public, William St Clair, the so-called hereditary grandmaster, was

not even a mason; the Scottish masons needed a figurehead, and

William St Clair accepted the role. In less than six months, he went

from no-Mason to grandmaster, and then resigned his title of

"hereditary grandmaster", which had been created for one purpose

only: get one over the English.

Rosslyn Chapel is not a piece of a puzzle that people need to try and fit into its proper place. That approach has occurred over the past several years, and has been largely unsuccessful. Rosslyn Chapel has been described as "unique", and hence it needs to be looked as a mature, stand-alone piece of architecture. In this approach, over the past several years, I was able to point out why Rosslyn intrigues and why it did become a central piece in Scottish masonry.

The reason why it was built where it was built, incorporates design features of a ritual landscape that go back to prehistoric times - they are very intriguing, but too complex to detail here. But all of this has nothing to do with the Sinclairs, but with the location of and the imagery used in the chapel. The chapel has been described as a "stone garden"; the chapel is dedicated with lush vegetation, is full of Green men; there is no obvious Christian imagery, except that inserted into it in recent decades by the churchgoers.

Remove that modern layer and you end up with some Christians who wanted to attend mass, but in the end decided against it, saying this was not a Christian place. William St Clair, in the middle of the 15th Century, was a tremendously wealthy person. He had his castle, but all his peers in Scottish matters of states, most of them much poorer than him, were erecting chapels in the style of a collegiate church: a church where certain priests lived, said masses and looked after the church.

The Setons of Prestonpans, a family which has possible connections with the famous alchemist Alexander Seton, built their collegiate church: it is largely without any decorations.

St Clair had much more money and brought in experts from France and elsewhere. To some extent, labor resource was scarce in Scotland, but at the same time, the French builders had a different legacy and knowledge. Furthermore, St Clair had been brought up as one of the most learned men in the country - by one of the most learned men in the country.

St Clair become personally involved in the building of the chapel and when he died before the completion of the church, his son was either unable or unwilling to continue; instead, he decided to close it off and leave it in its present state. The chapel's ground-plan was based on Glasgow Cathedral, the largest religious building in Scotland. The interior was then decorated with more than a hundred Green Men, according to some a pagan symbol.

If so, many Scottish churches have pagan connections, for even Glasgow Cathedral has its share of Green Men.

Green Man at Rosslyn Chapel

Other decorations, such as bag-pipe playing angels or death masks, have all been found in prominent churches in France; though odd for Scotland, it was not odd for the French workforce erecting the chapel.

What is unique, however, is the decoration of the three front pillars, particularly the so-called Apprentice Pillar. Vines circling to the top, dragons on its feet, one woman a few decades ago chained herself to it, saying she would not leave before the pillar was cut down, so that the Holy Grail, which she believed was inside, could be revealed.

She left shortly after making her point, but on one other occasion, apparently one person entered the chapel with a pick axe and was caught just in time before the pillar was demolished. As the pillar is weight-bearing…

What is the mystery of the Apprentice Pillar?

There is a centuries-old legend that argues that during the building of the chapel, the Apprentice Pillar was built by an apprentice, who disobeyed the orders of his master when he had gone to Rome. On his return, he found that the apprentice had finished the pillar, and as a result was killed: the Murdered Apprentice, a well-known theme in masonry. Though many books were written on Rosslyn Chapel, none had been able to explain why this story was told and what the importance of it was.

The reason is to be found in the fact that masonry has three degrees:

Each has its initiation ritual and early on, Rosslyn Chapel was chosen by the masons as a place for their services and initiations.

The three degrees are linked with the three pillars at the front. The three rituals are distinguished in where the initiate stands. And in Rosslyn, there is a small problem: to make the rituals work, you would expect that the most lushly decorated pillar marks the Master degree. But in Rosslyn, that is marked by the Apprentice.

And thus we have the story, I believe, of why the Apprentice was allegedly killed: to explain the anomaly. But that is what the masons made of the pillars. What did the builder try to convey when he ordered the Apprentice Pillar to be erected in that way?

The dragons encircle a vine that has been compared with a pillar, or a tree; the symbol is well-known in mythology and is pagan in origin: the world tree connected heaven and Earth, and the Underworld (the dragons at its base) and was used by angels ascending to and descending from heaven.

One such angel, the fallen angel, Shemhazai, is depicted on the wall not too far from the Apprentice Pillar. He was expelled from heaven and as punishment had to hang upside down, tied, from heaven. Is there an overall theme to the chapel? There is only one inscription in the entire church, and it is a quote from the bible - unremarkable, were it not for the fact that the quote is directly related with Zerubabbel, the builder of the Second Temple of Jerusalem. Zerubabbel is a major figure in freemasonry: he set the Jews free from captivity and rebuilt the Temple of Solomon, the central focus of masonry.

There is one depiction of a Masonic ritual, from the 19th Century, where the Apprentice Pillar has been used in a "boardgame" that marks the various steps of the initiation of a Scottish mason in his degree; the initiate is identified with Zerubabbel. Two authors with a more than casual interest in Rosslyn Chapel, Robert Lomas and Christopher Knight, have been claiming for several years that the chapel itself is based on the Temple of Solomon.

Their main focus is on the west wall of the building. This, they claim, resembles the wall of the Temple of Solomon; rather than unfinished, they believe St Clair wanted it to look like that, to mimic the temple wall. They claim it could never have been part of a larger church - even though there are drawings of much larger church for the site - as the wall itself is non-weight-bearing and hence could never have supported the larger structure.

So is there no hidden mystery?

The first potentially successful proposal came from two authors, Robert Lomas and Christopher Knight, whose first book, The Hiram Key, was launched inside the chapel in 1996. As a consequence, a proposal for non-destructive scans was created, which received the support of Historic Scotland. The Rosslyn Chapel Trust, however, first approved, then withdrew the permission.

To quote Knight and Lomas:

They declined, but a befriended scholar,

James Charlesworth of Princeton University, filed one their behalf.

The Trust has not acknowledged this proposal. Rumour goes that the

Trust have used the services of an Edinburgh firm to do

non-destructive scans, and that the results of this scan have been

kept a secret.

Niven Sinclair described the tunnel as "huge and very deep underground" at the point where it enters under the foundations of Rosslyn Castle. Beneath the floor of the crypt is a flight of steep steps, leading in the direction of the main building, to a vault directly underneath the engrailed cross in the chapel roof. A tunnel connects this vault with the castle; its location is directly below the south door, at which it is three feet wide and five feet high. Its roof is eight and a half feet below ground level.

After a straight run of approximately

twenty five feet, the passage turns ninety degrees towards the east

and then drops down the hillside, its roof twelve and a half feet

below ground level. The tunnel then continues under Gardener's Brae

towards the castle. Anyone can try and trace the tunnel in the

landscape; what comes immediately to mind is that the tunnel would

extremely steep in places. Robert Lomas and Christopher Knight have

highlighted that the design mimics the design of a similar tunnel

connecting the Palace of Solomon with the Temple of Solomon, as

mentioned in the mythology of freemasonry.

Then, the newspaper Scotland on Sunday (the Sunday edition of The Scotsman) complained about the "absent landlord" Peter Lougborough, the Earl of Rosslyn. Loughborough had been at the heart of a national controversy: in charge of police protection of the royal family. Loughborough's credibility was officially challenged when a stand-up comedian evaded the security measures during Prince William's 21st birthday party at Windsor Palace, gaining access and possible control of the royal family.

Bringing the national news story down to the local drizzle, the article reported that Loughborough had received large amounts of funding for the preservation of Rosslyn Castle, a house next to the Chapel (College Hill House) and the Chapel itself; yet the public had received no benefits from this public money; in fact, certain people had complained that access to the Castle had been refused, even though under the terms of the agreement, this should not be possible.

In fact, Loughborough seemed to receive

financial benefits from all, including, it seems, money paid from

the Trust to the Earl for the monstrous construction hovering over

the chapel.

When I approached the Project Director of the Trust about the creation of the book, and later of the existence of the book, I twice received extremely negative, but insightful comments. On the first occasion, he phoned, stating the book was seen as direct competition with their own guide, and as such would not be sold on the premises - despite the fact that this book is one of handful of books - and the first by a non-Sinclair or Sinclair-sponsored - solely dedicated to the chapel.

Though the various often outlandish theories about the chapel are published, like the Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln book, various mysteries get discussed and Rosslyn Chapel only gets a few pages or chapters dedicated solely to it. The book also goes against various unfounded allegations made in other books on sale in the bookshop, books which promote the fame of the chapel, but not the "understanding" of the chapel.

On the second occasion, the Director had

either forgotten the first correspondence, or chose to neglect it,

and informed me of his outrage that such a book had come about

without his approval!

This greatly upset the Project Director again, but there was nothing that he could do about the situation, as the area is not in the ownership of the Trust. The Trust, and particularly the Director, then embarked on a rather desperate campaign, which resulted in public mud slinging against Ritchie and various others, whereby - as always - far too willing and far too simple minds (as usual operating on the Internet) sided with the loudest, rather than the wisest.

One important stake was, of course, the known existence by Ritchie, as well as the Trust, of the subterranean tunnel, a major discovery which they knew would become public knowledge once the scans occurred. The fact that Ritchie had the eyes and ears of the international media meant the Trust could do nothing but wait, and blasphemy "the opposition".

The Trust was furious as this tremendous revelation would occur without their control - and reading from the evidence, one could argue the Trust actually tried to suppress awareness of the existence of this tunnel. In 2001-3, somewhat enigmatic modifications were made to one part of the crypt: they could be interpreted as a one-time attempt to foil plans relating to the tunnel - but plans, it seems, never carried out, hence resulting in a useless building.

Knight and Lomas describe parts of this work as follows:

Though it is doubtful the tunnel will reveal great secrets, the tunnel itself is a major discovery and as such, Lomas and Knight decided to incorporate it in their book, The Book of Hiram, published in 2003. This meant that the existence of the tunnel stopped being a local story, and entered the public arena. Where will it end and when will it be opened?

That mystery will continue to linger for

some time more…

The letter included this remarkable passage:

In 1556, she sent William St Clair to

France, to find more support for her daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots.

It underlines the close relationship Marie de Guise and the

Sinclairs had in the defense of the Scottish monarchy, a cause which

was always close to the heart of the Sinclairs.

There is some speculation that this included jewellery, which had gone missing and of which the Sinclairs were suspected for being involved in. However, it seems that such a secret would not be referred to as “The Secret”, nor would it require a letter from the Queen Regent, pledging her cause to Sinclair.

Rather than Sinclair pledging his

loyalty to the Queen Regent, it is the Queen Regent saying she will

obey the Sinclairs and not betray him.

Abbé Augustin Barruel (February 10, 1741 - May 10, 1820) was a Jesuit priest mostly known for creating a conspiracy theory involving the Knights Templars, the Bavarian Illuminati and the Jacobinians in his book Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (original title: Mémoires pour servir l’Histoire du Jacobinisme) published in 1797. He wrote the book while living in London.

Among other things he called

Adam Weishaupt, the leader of the Illuminati, “a human devil”. His basic

idea was that a conspiracy dating back through time existed, with

the aim of overthrowing Christianity.

He argued that the three stones were

secretly moved to Scotland after the Templar’s dissolution in 1312.

“The Knights of the Temple made them the foundation for their Lodge.

Their successors, heirs of the Secret, are currently the perfect

Masters of Freemasonry, the High Priests of Jehova.”

It opened the way for books such as the

Protocols of the Elders of Zion, another conspiracy tome from the

early 20th century, detailing the Jews were involved in a massive

conspiracy.

The two men were not acquainted and their respective works were written independently.

Professor Norman Cohn remarked that,

It is clear that Barruel made a lot of noise, and a lot of unfounded allegations.

Like

David Icke in the late 20th

century, his message of a conspiracy became more and more wild,

reaching a point of ridicule, whereupon the original promise and cry

of a conspiracy were completely lost amidst the stupendous and

ridiculous allegations that would follow afterwards - in Icke’s case

that the Queen of Britain, as well as many members of the British

royalty, were reptilian aliens in disguise.

In 1656, Fouquet had received a letter from his brother Louis, in Rome, in which he referred to an important secret which Nicolas Fouquet would be informed of next time they met. Louis Fouquet added that he had attained the secret from the French artist Nicolas Poussin, and that the secret itself was something that would move royals.

It seems that in the previous decades,

the French king himself had asked Poussin to confide in him - unsuccessfully, it seems.

If we were to believe Barruel, then it

is clear that treasures of the Knights Templar taken from the Temple

of Solomon at the time of the Crusades, specifically involving the

First Temple of Solomon and including stones connected with the Ark

of the Covenant do warrant a classification of a secret with a

capital S.

Should we read any significance into the presence of a gnomon on top of a gravestone in the cemetery?

Meridians were created for timekeeping.

They served as local timekeepers at first. Until two centuries ago, most cities, towns and villages would set their own time by the sun. For this, they established a “local meridian”. One often used technique was the gnomon, i.e. the sundial, which charts the shadow of the sun through the day to set the time and find the directions.

There were competing interests for the

location of 0°, especially with the French, who set their Zero

Meridian, known as the Paris Meridian so that it passed through the

greatest possible uninterrupted landmass in France, passing through

Paris in the North and Carcassonne in the South. In the end it was

at a conference in Washington, USA in 1884 that Greenwich was

chosen, because of the overwhelming influence of the British Empire

and its Navy.

Are there any specific features north

and south of Rosslyn that might indicate the presence of such a

local meridian?

Although it is now known that this account is not accurate, several Sinclairs have been buried inside the Abbey. At least seven of the

stones in the floor of Holyrood Abbey are memorials to Sinclairs,

although most of them date from the 18th and 19th Century.

Thanks to the presence of the canopy and its walkway, we are able to look over the new walls and buildings that would otherwise obscure the view… but which were absent when the chapel was erected. Most intriguingly, Arthur’s Seat is visible as a twin-peaked mountain.

Furthermore, it is the only mountain

visible above the northern horizon. Imagine that there are no

houses, and then Arthur’s Seat could be seen to rise as the only

hill above the northern horizon. Even today, in sunny weather, it is

a magnificent view… though somewhat difficult to discover as one is

distracted by the modern buildings.

There was a mounded or conical hill to the north or south of the palace and on its axis, a higher mountain, with a cleft summit or double-peak, further away on that axis.

In fact, Scully’s observations have since been found elsewhere in many cultures and in the “holy places” of Europe - though with variations.

The themes are there, but the interplay of the various features is sometimes slightly different.

Rosslyn Chapel, however, has been set on top of a hill, which stands above the Castle.

Can it be a coincidence that this age-old mythology is present in Rosslyn Chapel? Or was it by design?

Therefore, to observe this feature above Arthur’s Seat, one would have to be South of Arthur’s Seat, with College Hill, where the chapel was built, a perfect location to make astronomical observations. So, as Arthur is the Great Bear circling around the Pole Star, which is visible (from Rosslyn Chapel) above Arthur’s Seat, this could be one reason why the mountain was renamed: it “anchored”, or “sat” Arthur, who ruled the land.

Perhaps the two peaks were compared to two “pillars”, marking the entrance to the World of the Dead, where St. Peter greeted the dead with the key to heaven.

And what about the two pillars of

freemasonry?

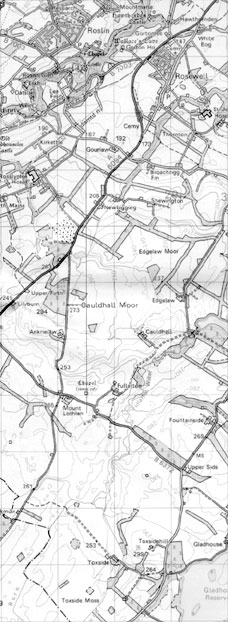

It is, however, “merely” a low hill. The hill is crowned by a grove of thirteen sycamore trees, the thirteenth being set off-centre. In the centre of the grove is the ruin of a 14th Century chapel, dedicated to St. Mary.

Mount Lothian marked the western outpost or gate of Balentradoch, the Templar headquarters of Scotland. It was the location of a Cistercian abbey, to which the chapel belonged.

The chapel is now in ruins, but once, it was the place where William Wallace was knighted - the scene made famous in the 1995 Academy Award winning movie “Braveheart”.

The name “Mount Lothian”

also suggests it is an important place, the primary mountain for

Lothian and therefore possibly the location from which the ruler of

the Lothians ruled.

Geoffrey presents him as a supporter of Arthur, and already King of Lothian, whom Arthur placed on the throne of Norway - a country with connections to the Sinclairs when they acquired the Orkney Islands.

However, maybe mythology had

him rule from Mount Lothian, and as a result, this sacred place was

later converted into a chapel. As Lot ruled the Lothians as a

nation, the Scots looked upon William Wallace, at his knighthood, as

the Guardian of Scotland, and looked to him to make free it from

English rule.

If by design, then the setting of Rosslyn Chapel within the landscape was a deliberate attempt by William St. Clair to make his kingdom a magical setting; a magic kingdom, very much like the concepts of Camelot and other Arthurian and Grail traditions with which William St. Clair must have been familiar.

Furthermore, as we have seen, his

teacher, Gilbert Hay, definitely knew about such legends, and

stories about the Earthly Paradise, or the Garden of Eden.

Collegiate churches housed a college of priests, whose role was to pray each day for the souls of the Lord and his family, whereby, it was hoped, their path to salvation would be eased.

One such “college collegiate church” is Crichton Collegiate Church, dedicated to St Mary & St Kentigern, which lies, quite literally, at the end of the road - and not far from Rosslyn.

A few hundred yards of single track road separate it from Crichton Castle, already another parallel with Rosslyn, where castle and chapel were set apart from each other too, in the same sequence, and with the same intervisibility between the two structures.

His family fortunes were raised by his son, William, the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, who became, during the minority of James II, the most powerful person in the kingdom.

Crichton Castle had been built in ca. 1400, but was attacked and damaged by the Douglas family in the early 1440s.

William Crichton spent much of his life quarrelling with the powerful Black Douglases. Crichton was responsible for the famous "Black Dinner" in Edinburgh Castle at which the Sixth Earl of Douglas and his brother were murdered.

The king was further displeased when allegations were made in 1484 that Crichton was plotting against him: the family's titles and possessions were forfeited. As quickly as the family had risen in the ranks of nobility, even faster they had fallen.

In 1488, Crichton Castle was among a number of properties bestowed by James IV on the Earl of Bothwell.

After the rise and demise of the Crichton family, the Reformation of 1560 swept away the system of collegiate churches in Scotland.

By the time the new owners embarked on a major program to rebuild Crichton Castle in the 1580s, the chapel was already in a state of disrepair. Still, in 1641, the church formerly known as collegiate became Crichton’s parish church.

Its near neighbor Rosslyn, meanwhile, remained largely neglected, until a series of visitors descended on the chapel, eventually leading to its reopening in the late 19th century.

The latest series of restoration work was carried out in 1999, to coincide with the church's 450th anniversary.

Apart from sharing a largely similar history, Crichton and Rosslyn also have several structural similarities, though in execution, Rosslyn was far more eccentric; the Sinclairs were definitely trying to outdo their Crichton neighbors.

But though less elaborate, it was elaborate enough, and in size, there is little difference between the two buildings.

The seats were later chipped away. On the north wall, there is a niche or aumbry, where the sacraments would be housed.

Traces of such structures are today absent from Rosslyn’s interior.

As such, in Rosslyn, the north door has far more “demonic” illustrations than the south door.

Like Rosslyn, Crichton church and castle have attracted painters, including JMW Turner, who sketched the church in 1818 while he was painting the castle.

As at Rosslyn,

there are rumors of a secret passage between church and castle,

which at Crichton was called the Velvet Way. A search for it was

made in 1867 - without success - and thus as in Rosslyn, its

existence remains shrouded in mystery. Unlike Rosslyn, no-one seems

to suggest it might contain a treasure. Endless speculation also exists why Rosslyn was built where it is. Some have argued that it was for the presence of a Temple of Mithras or a megalithic structure that existed there. In Crichton, evidence of Pictish and Roman settlements have been found very close by and everyone agrees that Christians probably worshipped on the site of the present church even before the first building was constructed - perhaps as much as a millennium before the Collegiate Church was erected.

And thus, we know that formally,

Crichton Collegiate Church is older than Rosslyn, but whereas there

is no trace of whether there was anything at Rosslyn Chapel before

ca. 1440, there is more consensus as to what there was at Crichton.

One is the older brother, the other the

more extravagant one; but both chapels were part of the same family,

with several more brothers and sisters located throughout southern

Scotland.

The Knights Templar first came to Scotland in 1128 during the reign of King David I, whom Hugues de Payens visited as part of his international recruitment drive. De Payens made a very favorable impression on King David, to the extent that he later surrounded himself by Templars and appointed them as “the Guardians of his morals by day and night”.

As a result of this Royal favor, through gifts from both the King and his Court, the Templars acquired a substantial property holding in Scotland.

There were two major Preceptories at the time: in Midlothian, there was Ballantradoch, also known as Balintradoch or a number of other spellings, but now renamed Temple, which was regarded as the main Preceptory and the administrative headquarters of the Order in Scotland; the other was at Maryculter in Aberdeenshire, on the southern bank of the River Dee.

The centre at Temple was opened in 1129.

It is alleged that Hugues de Payens was married to Catherine St.

Clair, whose family had given the land to the order. However, there

is no evidence for these allegations. The Sinclairs were not present

in the area at this time and it is known that Ballantrodoch was

donated by King David I himself.

But despite this

allegiance to the English king, the Knights Templar suffered a

similar fate to their French brethren.

They were tried in 1308 by an ecclesiastical court, presided over by William de Lamberton, Bishop of St. Andrews. The Knights Templar were prosecuted by John Solario, the papal legate to Scotland. During the trials, both Henry St. Clair and his son William were called as witnesses. Researcher Mark Oxbrow points out that this evidence is at odds with the popular accounts, which state that the Sinclairs were the Knights’ protectors.

The evidence suggests nothing of the kind. In fact, the Sinclairs stated that they felt the Knights Templar were of no good, for “if the Templars had been faithful Christians they would in no way have lost the Holy Land”.

A local legend states:

French legends about the Templar treasure apparently also state that the treasure was taken to Scotland, with the knights landing on the Isle of Mey, the first island they would encounter in the Firth of Forth.

Geographically,

this would take them to the mouth of the river Esk, which could take

them on to Rosslyn - though this is theory, since seafaring ships

would find it virtually impossible to reach that far inland. A route

over land would definitely have been easier.

This design has been linked to masonic

degrees, but in truth, the motive is quite common, and was a

“memento mori”: a reminder of death, expressing the knowledge we

must all die eventually.

It cannot come as a surprise that a writer of Scott's fame had a famous library, containing over nine thousand rare volumes.

Scott’s love for Rosslyn Chapel is expressed in one room, where carvings from the chapel have been reproduced.

It should be stressed the room is not a

replica of the chapel; instead, the decoration of the room is based

upon the decoration of Rosslyn chapel.

It is here that excavations have uncovered details of how medicine was practiced in one of the biggest and most famous hospitals in Europe.

Situated along Dere Street, which connected Newcastle to Edinburgh (the route of the A68), it was a medieval highway, whereby the hospital functioned both as a hotel, first aid, spiritual retreat and hospital.

Archaeological discoveries on the site have revealed the use of hallucinogenic substances, used during the treatment of patients, particularly as anesthetics.

The small remaining building is in itself not worthy of a visit, but the views from the Aisle over the Lothians, the Pentland Hills and the coasts of Fife are spectacular - weather permitting.

Videoclip of Soutra Aisle

There are coal deposits in the area and these are most likely linked to the water in the well which has an oily balm on its surface. This is a black tarry substance which was an effective ointment for some skin complaints and was also used to relieve the pain of sprains, burns and dislocations.

As well as treating eczema, it was alleged that this well was used for treating leprosy, Robert the Bruce being one of its patients. This speculation is based on the assumption that Liberton is derived from “Leper-Town”, but this is known to be incorrect. There is also no evidence to suggest that there was a leper colony near here or that lepers are connected with the well.

In 1650 Cromwell’s troops demolished the

well. Over 200 year later, in 1889, the well-house was once again

carefully rebuilt. Inscription belongs to Lord Prestonfield.

But in the early 19th Century, this was

rebuilt as a house, and is now The Balm Well restaurant.

This article appeared in 'Les Carnets Secrets 9' (2007)

St Bertrand de

Comminges

Its cathedral, known popularly as the “Cathedral of the Pyrenees”, is a major tourist attraction. Like Rosslyn, it does not need an esoteric dimension to shine. It has a magnificent organ, which has been labeled one of the three beauties of the Gascogne region. It has an enigmatic crocodile hanging from the wall.

Popular opinion has it that it crawled up the river, beached itself and that St Bertrand (from whom the town takes its name) killed it with the power of his prayers. More likely, the crocodile was an ex voto, brought back from the Middle East by a pilgrim or a knight, as a gift to the church.

There is beautiful tomb of St Bertrand, as well as extraordinary wood carvings.

It is believed that in 72 BC Pompey, a Roman General, was victorious in Spain, and upon his return, established a town here. The local tribe was labeled “the Convenae”, “the assembled ones”. Lugdunum shared its Latin name with Lyon (perhaps why it received Convenarum attached to it), which is largely accepted to mean “Fortress of Lug”, the sun god.

It was the Jewish historian Josephus who wrote that Caligula punished Herod and sent him to “Lugdunum”, which was a city in Gaul. In another text, Josephus added that Herod went into exile to Spain, but ended his life in what everyone accepts is St Bertrand de Comminges.

Though we do not know where he may have been buried, or lived, the claim is largely undisputed.

It is therefore of interest to note that the town had one of the oldest churches in Gaul - though the present cathedral was not the site of the first church.

In fact, it is possible, after archaeological considerations of the substructure of the cathedral, that it may have once been the location where a pagan temple stood. The original church was near the Chapelle Saint-Julien du Plan, at the foot of the hill. There are records from 409 AD confirming the presence of a “Christian basilica”. A basilica is a specific term, arguing for the conclusion that the site held a precious relic.

As archaeologists have found no further

evidence for this, they argue that the term may have been loosely

applied. If this was Rosslyn, Herod’s presence, its status as an old

church, the possibility of a precious missing relic… someone would

conclude that relic could only be the head of John the Baptist,

taken here by Herod himself. But this is not Rosslyn.

This church is constructed with numerous remains of previous sacred - and pagan - structures. It is accepted that the location was once the site of “a privileged necropolis”. The church once had a relic of the True Cross and is linked with the martyr Saint Just.

It is most remarkable for the martyr’s relics stored in a stone sarcophagus.

This sarcophagus sits at the far end of the church and pilgrims could walk and stand underneath the sarcophagus, which was a novel custom of the time, whereby pilgrims believed that close proximity if not actual contact with the tomb of a martyr was the most powerful method for the pilgrim’s prayers to come true. Hence why the tomb was raised and pilgrims could pass underneath.

Trevor Ravenscroft would have drawn a parallel to Rosslyn here too…

They are gigantic, so much so that most tourists will fail to spot them.

The second man linked with the town is another Bertrand - Bertrand de Got.

He was Bishop of Comminges from 1295 to 1299. In 1304, he became archbishop of Bordeaux, but continued to have a specific devotion to his former residence: he made sure that the foundation stone for a series of extensions - the current cathedral - was executed.

In 1305, Bertrand de Got became Pope Clement V, the first pope of Avignon, though he was elected in that other Lugdunum, Lyon. It could be a coincidence… In 1309, he went on a pilgrimage, on January 16-17, 1309 visiting St Bertrand, where he “elevated” the relics. A papal bull explains the details of the event.

He built “the church of wood in the church of stone”, executed in the Renaissance style and inaugurated on Christmas 1535. The central area of the church is fenced off by a majestic wooden rectangle. Inside of this is the “church of wood”: a smaller church, for the privileged, made up out of 66 stalls, on two levels (38 on top, 28 on bottom), each and all supporting some of the most magnificent wooden carvings.

Here, again, we find depictions of angels, Green Man and other enigmatic features.

There is a depiction of Jesse’s tree; more remarkably still, are the depictions of various Sibyls, pagan oracles that the Church was able to weave into its mythology, but which are totally a totally unexpected - though highly welcome - sight at the foot of the Pyrenees. As in Rosslyn, you will expect to see an enveloping theme, but like Rosslyn, you leave the cathedral what that story could be.

Why remains unclear, though it is known that at the time of this assignment, he was equally elevated to be chaplain to Pope Boniface VIII (1294-1303), who made him archbishop of Bordeaux in 1299 - a required step if de Got ever aimed for the papacy.

But according to the contemporary chronicler Giovanni Villani, there were rumors that he had bound himself to King Philip IV of France by a formal agreement previous to his elevation. It puts Clement’s agreement to disband the Templars a few years later in a different light, each having desires and ambitions with which the other had, or wanted to agree.

Some in the papal parade were injured too; the pope himself lost his balance and a precious stone loosened from his tiara - to be lost forever.

Rosslyn lacks a pope. It also lacks miracles, unlike St Bertrand de Comminges.

St Bertrand’s canonization was supported by a document detailing a list of no less than 31 miracles. One of these involved the corn of a unicorn, today still on display in the treasury of the cathedral. In truth, it is a tusk of the Arctic Narwhal (monodon monoceros), a species of whale.

Though the object may seem to be without too much interest, it is reported that Bertrand de Got had a veritable fascination with it; and so, it seems, had the larger community, as the object was used in a festival that commemorated one of the miracles performed by St Bertrand.

It claims that Clement V was so obsessed with this unicorn that he worked it into his papal cross. He instructs three Templars form the nearby commandery of Montsaunès to guard over the relic. But, the text continues, when the Knights Templar were arrested and afterwards abolished, Clement V made a special dispensation for these three guardians.

He informed them that if they continued to guard this relic, they would not be arrested, nor interrogated, definitely not thrown in prison, or killed. In return for this exceptional clemency, all they had to do was guard the relic - and apparently after their and the order’s demise, had to elect and prepare their successors to continue to safeguard the relic.

One question should be asked: is it possible that the guardianship of this “unicorn” was but an excuse? Could it be that the Templars instead guarded something far more precious? Perhaps…

And no doubt, someone could conclude that this

precious relic may have been the Grail… or Baphomet? And when we

“know” that Baphomet, the idol apparently worshipped by the Templars,

was “apparently” a bearded head… the head of John the Baptist? It

does make sense, doesn’t it? All that is missing, is a link to the story of Rennes-le-Château. And we do not even need to invent one. The story goes that in 1285, one Pierre de Voisins, lord of Bézu, just south of Rennes-le-Château, required the arrival of a group of Knights Templar, who come from the Roussillon. Why he chose to have Templars sent from so far whereas there were other commanderies nearby is not known.

Officially, they were there to protect the pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostella, but the rumor goes that they were there to exploit, bury or survey a treasure - or secret. Like the Templars in St Bertrand de Comminges, this contingency is not arrested. It is also known that at that time, they were under the command of a lord known as “de Goth” - the same surname as the pope.

If you need to work a bloodline into this story, we should know that “de Got(h)” was derived from Visigoth, the tribe which various authors have already identified as being of the bloodline.

But we won’t go into that direction.

Is it therefore not rather remarkable

that a descendant of a grandmaster of the Knights Templar would be

the one who is responsible for the abolition of the order, but that

we have at least two locations where for rather unclear reasons,

certain arrest warrants were not given, likely through the direct

intervention of Clement V, whom in the case of Bezu seems to have

had a family member in charge and whom in the case of St Bertrand de

Comminges appears to have had a personal desire to protect precious

relics?

So where did he take it to? The Scottish Rosslyn?

In 1306, with Clement in charge of the Knights Templar and a year to go before their arrest, the de Got family expanded the chateau and made it into a veritable fortress, in the years 1308 to 1310.

The nephew Bertrand de Got was responsible for the works, which resulted in a 3000 m² fortress complete with eight round towers. It was a war machine, well equipped to defend the valley and its produce, and the roads passing. The money for this operation apparently came from the Knights Templar.

The question, therefore, is whether this castle is perhaps a possible location where a “precious Templar relic” was hidden.

And that might make it not only the “French Rosslyn”, but the “real” Rosslyn.

|

some

350 million years ago.

some

350 million years ago. North

was linked to the World of the Dead. In some cultures, the sacred

mountain to the north was sometimes called “Storehouse of the Dead”.

The twin-peaked hill between the temple and the “Everlasting Stars”

of the North was thus considered to be a way-station to “Heaven”.

North

was linked to the World of the Dead. In some cultures, the sacred

mountain to the north was sometimes called “Storehouse of the Dead”.

The twin-peaked hill between the temple and the “Everlasting Stars”

of the North was thus considered to be a way-station to “Heaven”.