|

in Denali National Park, Alaska.

Photo by Karel Stipek didn't create art and architecture out of nothing.

They took inspiration from the nonhuman world...

We were not alone...

As we journeyed, we came into contact with other large-brained hominids, including our closest extinct relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans.

But by the end of the

Pleistocene,

around 11,700 years ago, only Homo sapiens remained.

Over time, these lines hardened into barriers.

But how did culture begin?

We have stories for that too. In one well-known myth, as set down by Plato in the 4th century BCE, the gods charged two Titans, Epimetheus and Prometheus, with the task of fashioning mortal creatures from earth and fire and equipping them with the qualities they would need to survive.

Epimetheus began doling out strength and speed; the capacities to fly, swim or burrow; shells, warm fur, thick skin, hooves, claws and other qualities.

However, when it was time to bestow a gift to humans, the Titan realized he had nothing left to give.

His brother, Prometheus,

not knowing what else to do, stole fire from the god Hephaestus and

gave it to humans, along with the knowledge essential for their

survival - gifts for which he was eternally punished.

Through Prometheus, humans became elevated above the beavers, bison,

bears and other creatures.

In this tale, news outlets report that bears across the midwestern and southern United States are making fires. Instead of hibernating, they plan to spend the winter keeping their fires going along the medians of interstate highways.

Scientists propose that warming winters have changed the bears' hibernation cycles, a shift that has allowed them to remember things from year to year, including the fact that they had made their discovery centuries ago.

When the narrator eventually sits with the bears around their fire, he notices that they do a pretty good job of tending it, but haven't quite figured out the right kinds of wood to burn.

Bisson's alternative version of the Promethean tale was first published in a science-fiction and fantasy magazine.

It's 'fantastic' because it seems so unlikely:

In the few decades since Bisson's story was published, our understanding of human exceptionalism has been coming apart.

In the archaeological record, the line between what has traditionally been considered human culture and animal instinct is blurring in ways that challenge our conceptions of culture and history.

Far from the stuff of myth or science fiction, archaeological evidence suggests that some of our human ancestors were prompted to make art by engaging with the marks left behind by other species (by bears, in fact).

Early humans may also have been inspired to build wooden structures by observing beaver dams, and learned to cultivate certain plant species by paying attention to the seeds that grew along bison trails.

In other words:

Prometheus had nothing to do with it.

Exploring that question involves reconsidering not just archaeological evidence but the discipline of archaeology itself.

As opposed to anthropology, which studies anthropos (the 'human'), archaeology, by definition, is not limited to our species alone:

Yet most archaeologists (and the Oxford English

Dictionary) will tell you that the discipline involves the study of

past people, often through the systematic excavation and analysis of

anything that falls under the wide umbrella of 'material culture'.

Although there are probably as many definitions of culture as there are examples of it, most describe culture as something that is learned rather than inherited.

These cultural traits are passed on from one generation to the next not through genes, but by observing and copying established skills. Processes of cultural transmission involve imitation and innovation, practice and progress - and these all leave traces in the ground.

Those traces can take a remarkable variety of forms, from shards of

broken pottery to ancient dental calculus (calcified plaque) on

buried teeth.

It can tell us about feasts and gift-giving practices, and may even reveal something about old stories and myths.

Calcified dental plaque on teeth can trap and

preserve microscopic remains of food debris and microbes, which

archaeologists can use to learn about diet, health, diseases, the

environment, and perhaps even the cultural or ethnic affinities of

past people.

cultural making and doing that we consider to be uniquely human

was being done by animals

first?

Zooarchaeologists like me are trained to identify the remains of other species from archaeological sites by analyzing bones, teeth and shells.

To put it simply:

This is based on a well-established belief:

When animals make and do things, we call it instinct, not culture. When the things they make and do change over time, we call it evolution, not history.

Anthropologists have pointed out that this is an unusual way of thinking:

The unique trajectory afforded to humans compared with all other animals is evident in paleoanthropologists' use of the phrase 'anatomically modern humans'.

This terminology tries to make sense of the fact that there were members of our species hundreds of thousands of years ago who had the same morphological characteristics and physical capacities that we have today, but who seemingly had not yet taken the step into a new world of culture.

By contrast, as the British anthropologist Tim Ingold argues, we never speak of 'anatomically modern chimpanzees' or 'anatomically modern elephants' because the assumption is that those species have remained entirely unchanged in their behaviors since they first took on the physical forms we see today.

The difference, we assume, is that they have no

culture.

with lines and

patterns on a textured stone surface. dating back about 30,000 years in the Cussac cave at Le Buisson-de-Cadouin, Dordogne, southwestern France. Photo by Christophe Archambault AFP/Getty Images

Think of the way that mark-making incites more mark-making:

And deep inside caves across Europe, some of the earliest evidence

of human paintings and engravings made by our ancestors and their

relatives - dating back 65,000 years or more - echoes marks left by

other animals.

These early marks were often placed around or atop the polished surfaces and claw marks left behind by cave bears, felines and other mammals. Sometimes the human marks imitate the forms of existing scratches or smoothing made by other species.

Human art, then, is part of a

broader tradition of animal mark-making.

In the 1960s, for example, the French prehistorian Amédée Lemozi interpreted a series of engraved lines at Pech-Merle cave in the Occitania region of southern France as a representation of a masked and wounded shaman.

Lemozi saw lines piercing the figure of the shaman and pecking intended to represent wounds, leading him to suggest that the shaman was depicted undergoing a ritual death.

Lemozi's ideas were taken up by the Belgian prehistorian Lya Dams in the mid-1980s and extended into a broader exploration of wounded men in Palaeolithic art.

A few years later, however, the French prehistorian

Michel Lorblanchet showed that the many crisscrossing

lines making up the 'wounded shaman' on the calcite surface of the

cave were, in fact, gashes in multiple directions left by the claws

of cave bears.

laid the literal and figurative foundations

for human art...

A decade later, in the cave of Les Battuts in Tarn, France, the French prehistorians Edmée Ladier and Anne-Catherine Welté and the speleologist Jacques Sabatier believed they had found distinctive human-made 'tectiform' signs ('roof-shaped' geometric designs thought to represent structures or dwellings).

But they soon realized the marks were overlapping striations made by cave bear claws.

Such claw marks are the best-studied type of animal markings in caves, but many other species are known to leave potentially confusing traces with their claws and horns.

Bednarik, who has spent decades dedicated to the work of distinguishing between different markings through his Parietal Markings Project, suggests that the most numerous animal markings in caves are likely those created by bats.

As Lorblanchet and the British prehistorian Paul Bahn wrote in

their book The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art

(2017), the issue of clearly differentiating between human and

animal behavior on cave walls 'is a fundamental problem in the

birth of art'.

According to their theories, humans progressively realised that the marks they made unintentionally resembled elements of the world around them.

Such marks might appear in the process of scratching on bone or stone during butchery and tool-making, or accidentally brushing pigment against the walls of narrow cave spaces.

Those accidental discoveries allegedly opened the door to the intentional production of images that resemble things.

Yet, even where marks can be

differentiated between those made by animals and humans, separating

ideas from instincts, or inspiration from imitation, is complicated.

In Aldène cave in the south of France, human artists 'completed' earlier animal markings.

More than 35,000 years ago, a single engraved line added above the gouges left by a cave bear created the outline of a mammoth from trunk to tail - the claw marks were used to suggest a shaggy coat and limbs.

In Pech-Merle, the same cave where Lemozi mistook cave bear claw marks as human carvings of a wounded shaman, a niche within a narrow crawlway is marked by four cave bear claw marks.

These marks are associated with five human handprints, rubbed in red ochre, that date to the Gravettian period, about 30,000 years ago.

For Lorblanchet and Bahn, the association between the traces of cave bear paws and human hands is no accident:

Nonhuman carvings laid the literal and figurative foundations for

human art.

Vitruvius, a Roman architect and engineer of the 1st century BCE, hypothesized that humans were inspired to create architecture by observing how birds and bees built their nests and hives from natural materials to shelter themselves against the elements.

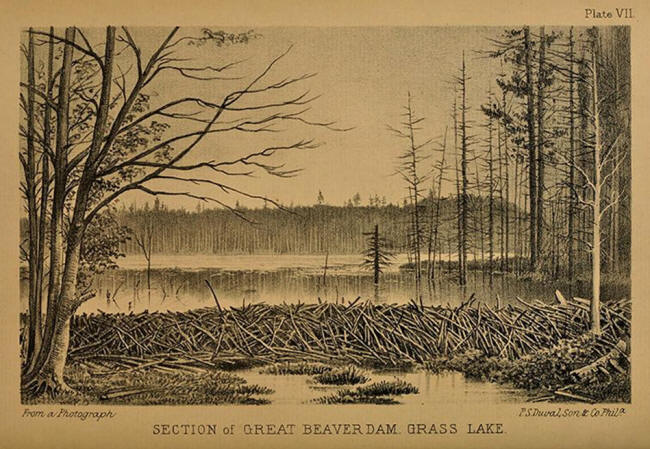

In the late 19th century, the lawyer, ethnologist and railroad profiteer Lewis Henry Morgan made similar observations about the parallels between human-made architecture and the structures produced by North American beavers.

In his book The American Beaver and His Works (1868), Morgan wrote that this 'architectural mute' of Michigan's Upper Peninsula offered,

Morgan marveled at the craftsmanship, strategic placement and 'highly artistic appearance' of the beaver dams, which he systematically studied through destructive excavations that any archaeologist might find familiar.

Morgan produced meticulous maps, drawings and

photos to document beaver construction styles and techniques, and to

illustrate how dams and lodges were adapted to the unique conditions

and character of each stream.

Engraving of a beaver dam in front of a lake surrounded by trees

labelled “Section of

Great Beaver Dam, Grass Lake.” by Lewis Henry Morgan. Courtesy Wikimedia

In the area that is now North Yorkshire, England, beavers began settling along the edges of a lake formed at the end of the last Ice Age, known as Lake Flixton.

Drawn by the mixed forest of birch, aspen and willow, the beavers dammed small streams around the lake, creating new ponds, wetlands and marshes.

Those environments attracted a variety of wildlife, including fish, waterfowl, red deer, elk, wild boar, foxes and wolves.

By about 10,000 years ago, it appears that beavers had

cleared the forests from the edges of the lake and created habitats

full of fish and game animals, enticing humans to settle nearby.

with architectural models and the very materials

with which to build structures...

The

archaeological site of Star Carr, for

example, which was excavated between 1949 and 1951, yielded some of

the earliest examples of wooden-made structures in Europe, including

a seasonally occupied timber platform along the shore of Lake Flixton.

Coles and Orme had been working at a site known as the Somerset Levels, where, like Star Carr, ancient wooden remains had been preserved in waterlogged wetlands and peat.

Remains from the Somerset Levels included a timber platform similar to the one identified at Star Carr but dated later, to the Neolithic period (about 6,000 years ago).

When Coles and Orme examined the platform preserved at the Somerset Levels, they noticed about 40 of the logs used in its construction were unusual: they had not been snapped or chopped cleanly across.

Instead, their ends had been cut with a series of parallel facets, a pattern that could not have been produced by Neolithic stone axes or knives.

oles and Orme realized

these had been felled by beavers and used to build wooden

architecture before humans repurposed the materials for their own

structures.

An archaeological dig site

with wooden

debris and a person examining the ground nearby. Courtesy the Star Carr Project

CC BY-NC 4.0 An ancient wooden item with pointed ends and a scale for measurement in centimeters below. Wood recovered from Star Carr showing chop and tear at distal end (right) and beaver gnawing at the proximal end (left). Courtesy Michael Bamforth, Star Carr Project CC BY-NC 4.0

They immediately recognized the same tell-tale marks of beavers on some of Star Carr's birch branches. Coles and Orme went on to review evidence from many other prehistoric sites across England and Wales.

They eventually identified wood with beaver facets in multiple human constructions, along with extensive networks of ancient beaver dams and channels that had been integrated into prehistoric settlements.

For millennia, beavers built the lake landscapes and fertile hunting grounds that made human life flourish.

As Coles and Orme showed, these animals also provided people with architectural models and, in some cases, the very materials with which to build structures.

Yet,

the histories we write about

Star Carr begin with the human

platform-builders, not the beavers.

Video

also

HERE... of the platform at Star Carr.

Courtesy the

Star Carr Project

That attention also extended to plants. About 8,000 years ago, in the tallgrass prairies of eastern North America, bison fertilised soils, transported seeds, and encouraged the growth of barley, wild squash, sumpweed and sunflowers.

Bison, like beavers, are what ecologists term 'keystone' species - organisms that hold an environment together, sometimes affecting its structure, character and composition.

In tallgrass prairies, bison preferentially graze grasses, especially when the shoots are young and tender, which allows more flowering plants to grow and increases species diversity. Bison also wallow in mud or shallow water to keep cool and avoid insect bites.

In the process, they disperse the seeds

of plants stuck to their fur, which easily sprout in the

well-watered and nitrogen-enriched clearings of bison wallows.

people and bison became partners in engineering the ecosystems

of the prairies...

Based on fieldwork in the Joseph H Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in eastern Oklahoma, the archaeologist and paleoethnobotanist Natalie Mueller and her colleagues have argued that North American humans who foraged in these landscapes would have noticed the mutualistic relationships between bison and certain plants.

As bison moved through the prairies, they created clear trails through the grasses.

Travelling along those bison tracks, people would have encountered

dense stands of seed-bearing annual plants growing where bison

grazed and wallowed.

However, growing in dense stands in bison-made clearings, these same species would have offered an easier harvest. It's likely that this observation led humans to propagate and, eventually, domesticate such wild crops.

Over time, people and bison became partners in engineering the ecosystems of the prairies.

Mueller and her colleagues have shown how the archaeological sites with the earliest evidence for plant domestication coincide with paleoenvironmental sites with evidence for anthropogenic burning.

Humans, with our fires, cleared native forests and changed their composition, promoting growth in nut trees and wild fruits, and attracting game animals - including bison - to new edges and clearings.

The bison,

in turn, created niches for the annual seedbearing plants eventually

cultivated by humans.

Rather, it requires new ways of thinking.

It was once unimaginable that cave bears might share responsibility with our ancient ancestors for 'inventing' art.

Likewise, beavers, hunted to extinction in the British Isles by the late Middle Ages, are not the first explanation that comes to mind for architectural remains at English archaeological sites such as Star Carr.

And as

for bison, the outsize impacts they had on the biodiversity and

structure of tallgrass prairies remained unknown until recent

decades because grazing herds had disappeared long before the

discipline of ecology came into existence - such herds had been

intentionally eradicated as obstacles to the westward expansion of

European settlers.

That process of discovery was less about our species defining

itself against everything else in the world than it was about

interactions, observations, mimicry, creativity and experimentation.

Culture was never (only) ours...

In the archaeological record, Prometheus isn't a godlike Titan...

|