|

Video also HERE Waves of calcium, revealed by a fluorescent dye, ripple across a bed of astrocytes, showing that the cells actively signal. Warmer colors represent higher calcium concentration. The video was sped up from the original. Its resolution was enhanced using AI

with the creator's consent. how astrocytes tune neuronal activity to modulate our mental and emotional states. The results suggest that neuron-only brain models, such as connectomes, leave out a crucial layer of regulation.

By exchanging signals to depress or excite each other, they generate patterns that ripple across the brain up to 1,000 times per second.

For more than a century, that dizzyingly complex neuronal code was

thought to be the sole arbiter of perception, thought, emotion, and

behavior, as well as related health conditions. If you wanted to

understand the brain, you turned to the study of neurons:

neuroscience.

The experiments, in mice, zebra fish, and fruit flies, reveal that the large brain cells called astrocytes serve as supervisors.

Once viewed as mere support cells for neurons, astrocytes are now thought to help tune brain circuits and thereby

control overall brain state or mood - say, our level of alertness,

anxiousness, or apathy.

This anatomical arrangement perfectly positions astrocytes to affect information flow, though whether or how they alter activity at synapses has long been controversial, in part because the mechanisms of potential interactions weren't fully understood.

In revealing how astrocytes temper synaptic conversations, the new studies make astrocytes' influence impossible to ignore.

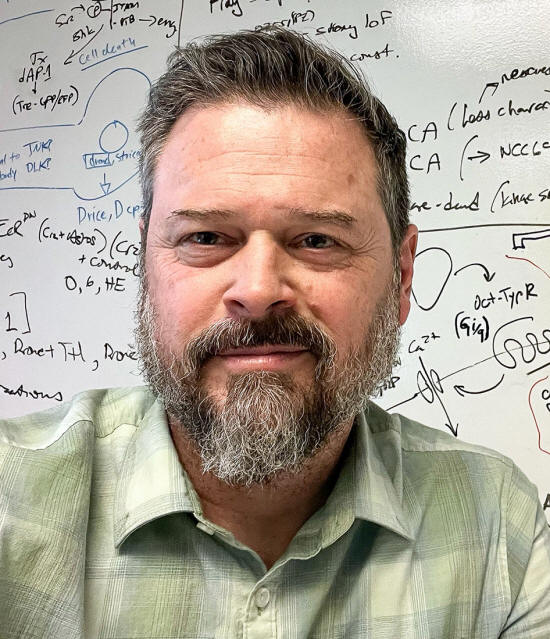

Marc Freeman's experiments on fruit fly astrocytes are leading the way in revealing how the cells can rapidly shift the brain's state. Unfortunately, he said, 99% of neuroscientists

don't consider astrocytes in their

studies.

Instead, they monitor and tune higher-level

network activity, dialing it up or down to maintain or switch the

brain's overall state. This function, termed neuromodulation, may

cause an animal's brain to switch between dramatically different

states, such as by gauging when an action is futile and prompting

the animal to give up, one of the new papers shows.

...said

Stephen Smith, an emeritus

professor of neuroscience at Stanford University who conducted

pioneering experiments in astrocyte signaling in the late 1980s and

early 1990s and was not involved in the new research.

While previous work has implicated astrocytes in some cellular signaling, the latest experiments use,

In that role, astrocytes could be major participants in sleep or psychiatric disorders that broadly disrupt the state of the brain.

A Star is Born

By the 1950s, researchers knew that astrocytes did more than that.

In experiments, the cells sucked up excess neurotransmitters, buffered potassium, and secreted substances that neurons require for energy. Like cellular alchemists, astrocytes seemed to be monitoring and adjusting the broth of the brain, keeping conditions favorable for neurons.

But scientists considered them relatively passive

regulators until the late 1980s, when Smith built a new microscope

for his neuroscience lab at Yale University.

pictured here with Banjo the Havanese dog, built a microscope in the late 1980s that prompted pioneering research

into astrocyte

signaling.

When a neuron fires, calcium rushes into the cell. So the researchers put fluorescent sensors into brain cells that glowed when they encountered calcium.

The microscope could detect the light as it brightened and dimmed over space and time, revealing the cells' firing patterns.

One day in 1989, Smith's graduate student Steve Finkbeiner (now a neurologist at the nonprofit Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco) was using the microscope to explore the potentially toxic effects of the neurotransmitter glutamate, the molecule most neurons in the brain use to communicate.

Finkbeiner was not interested in astrocytes, but because they help keep neurons alive, he put them in his cell culture.

Then he added glutamate.

Fluorescence rippled across the bed of astrocytes in waves, hopping from one cell to the next.

These calcium waves showed coordinated activity, as if the astrocytes were communicating with each other. And because the cells responded to glutamate, it was only logical that they would also respond to neurons.

In their 1990 paper (Glutamate induces Calcium Waves in Cultured Astrocytes - Long-Range Glial Signaling) describing the experiment, the researchers boldly proposed that,

Other teams soon showed that astrocytes in dishes, brain

slices, and even anesthetized animals responded to various

neurotransmitters.

Video also HERE... This video, taken in 1989, shook up the field of neuroscience. Fluorescence reveals waves of calcium, hopping from one astrocyte to the next, in response to glutamate, the molecule many neurons use to communicate.

Glutamate

was added at 0 seconds.

For one thing, astrocytes occupy relatively massive territory:

Astrocytes work on longer timescales than neurons do.

Their calcium waves spread over a

period ranging from seconds to minutes - much longer than the

milliseconds it takes for neurons to propagate signals down their

axons and release neurotransmitters.

Researchers tried to activate astrocytes in lab mice by bombarding them with sensory stimuli, such as by shining light in their eyes or touching their whiskers; they looked for a response through a cranial window under a fluorescent microscope.

Sometimes the cells responded, sometimes they didn't.

Then, in 2013 and 2014, two independent research teams reported a sure-fire way to get astrocytes' attention:

When vertebrate animals are startled, neurons in a brainstem region called the locus coeruleus release norepinephrine, a neuromodulator associated with arousal, along fibers that fan out across the brain.

Instead of sending a specific message, as neurotransmitters do, neuromodulators dial brain activity up or down and change the brain's overall state like a dial on a radio.

The studies indicated

that norepinephrine was the trigger for the astrocyte waves,

implicating astrocytes in neuromodulation in some capacity.

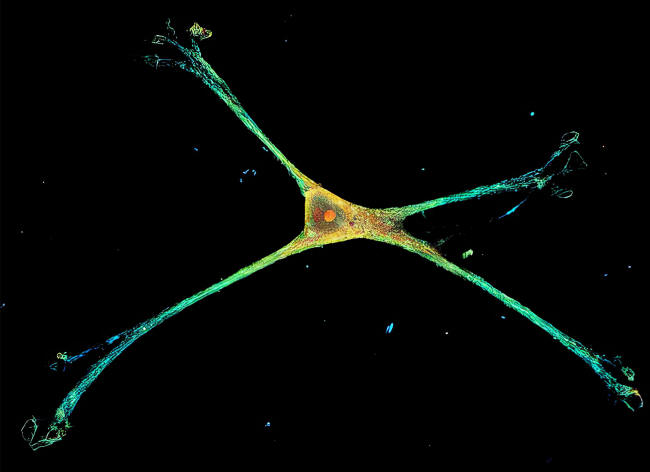

on a specialized nanowire structure. In its native environment, the cell would envelop hundreds of thousands of synapses, enabling it to monitor

and adjust neuronal signaling.

The cells were known to have norepinephrine receptors, but no one knew how the binding of norepinephrine led to the calcium waves. And there was still the question of what signal those waves sent to downstream neurons.

Some researchers thought astrocytes produced

their own "gliotransmitter" molecules that acted upon neurons, but

others disputed that notion. At meetings, researchers engaged in

loud, heated debates over how much - indeed, whether - astrocytes

shape the flow of information in the brain.

Ma forged ahead.

He replicated the startle response in fruit flies by suddenly flipping them upside down. Using the delicate tools of molecular biology, he traced the chemical relay:

It was critical to characterize such neuron-astrocyte interactions,

To some, the experiment provided the first proof that astrocytes are integral parts of neural circuits. But one fruit fly paper was not enough to sway skeptics.

Nearly a decade later, eerily parallel findings in a vertebrate would tip the scales.

It represents a change in mental state from hope to hopelessness that, like being startled, has profound effects on behavior.

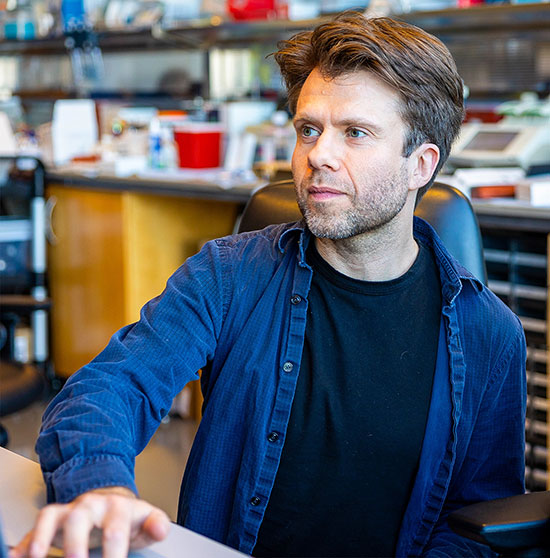

Researchers led by the

neuroscientist

Misha Ahrens were studying what

made zebra fish larvae give up when they made a discovery about how

astrocytes mediate such a sudden change in mood.

astrocytes modulate the switch in brain state from hope to hopelessness - specifically, to the state of giving up

after

engaging in a futile effort.

In the wild, if a zebra fish wants to stay put in flowing water, it will swim against the current. In the lab at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus in Virginia, Ahrens' team used virtual reality to create a simulation of a current in the zebra fish tank, so that a fish would think it was slipping backward no matter how furiously it swam.

The

fish would swim harder at first, but after about 20 seconds, it

would typically give up. A little while later, it would try again.

The buildup paralleled the number of attempts the fish

made to fight the current, as if the astrocytes were keeping track -

until at some point they issued a stop signal, and the zebra fish

gave up.

In an ensuing Science paper, published in 2025 (Norepinephrine changes behavioral state through Astroglial purinergic signaling), the researchers revealed how astrocytes caused these changes in behavior.

Using fluorescent sensors for various molecules, they found that when enough calcium builds up in astrocytes, they release the energy molecule ATP, short for adenosine triphosphate.

Outside the cell, the ATP is converted into adenosine, which acts on neurons - in this case, by exciting neurons that inhibit swimming and suppressing swim neurons.

This sequence echoes what Ma and Freeman

observed in the fruit fly.

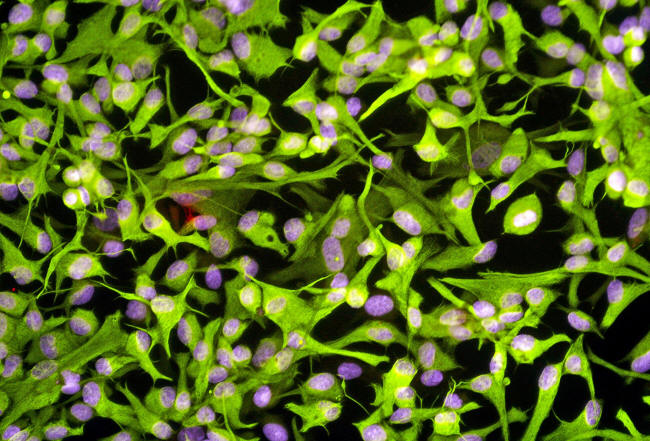

(seen here in a fluorescence light micrograph of human tissue) were considered mere support and scaffolding for all-important neurons. The new experiments reveal in great detail

the cells' influence over

neuronal signaling in the brain.

Papouin's team was studying changes at synapses that alter communication between neurons, a form of neuroplasticity that underlies ongoing shifts in thought and behavior. Norepinephrine was thought to produce these shifts by acting directly on neurons.

But to Papouin's surprise, norepinephrine's effects were apparent even when its receptors on neurons had been removed.

The process depended solely on astrocytes.

The finding of parallel molecular pathways in such distinct species as fruit flies, zebra fish, and mice points to,

The results suggest a gaping hole in previous theories of neuromodulation.

discovered that a type of neuroplasticity, which underlies shifts in thought and behavior, is mediated entirely by astrocytes,

neurons not required.

Freeman's postdoc Kevin Guttenplan doused a dissected fly brain with the fly versions of norepinephrine.

Norepinephrine and its analogues in the fly seem to enable

astrocytes to "hear" neurons' molecular messages and then modulate

their activity.

The results reveal a new complexity to how the brain processes information, Guttenplan said.

Working in zebra fish, Alex Chen observed the first known instance of astrocytes mediating a rapid transition

between brain states.

Some research suggests that astrocytes' ability to accumulate information over time (as happened with the zebra fish's swim attempts) extends to the sleep-wake cycle.

Astrocytes appear to keep track (A Role for Astroglial Calcium in Mammalian Sleep and Sleep Regulation) of people's increasing sleep debt throughout the day, likely through a buildup of calcium, (Astroglial Calcium signaling Encodes Sleep Need in Drosophila), and secrete sleep-inducing molecules that alter brain activity.

Those behaviors may reflect mental health conditions.

Last year, researchers revealed a neuron-astrocyte brain circuit that was triggered by stress and produced behavior resembling depression in mice.

People's moods change relatively slowly, Ahrens said, in a process partly driven by neuromodulators.

Astrocytes' role in neuromodulation points to their promise as a drug target.

The way to change that, he said, is to accept the existence and

influence of non-neuronal cells such as astrocytes, and to include

them in models and experiments.

|