WIRED: In the late '90s, when the

internet began to spread, there was a discourse that this would

bring about world peace.

It was thought that with

more information reaching more people, everyone would know the

truth, mutual understanding would be born, and humanity would

become wiser.

WIRED, which has been a

voice of change and hope in the digital age, was part of that

thinking at the time. In your new book, Nexus, you write that

such a view of information is too naive.

Can you explain this?

YUVAL NOAH HARARI: Information is not the same as truth.

Most information is not an accurate

representation of reality. The main role information plays is to

connect many things, to connect people. Sometimes people are

connected by truth, but often it is easier to use fiction or

illusion.

The same is true of the natural world. Most of the information

that exists in nature is not meant to tell the truth. We are

told that the basic information underlying life is DNA, but is

DNA true? No. DNA connects many cells together to make a body,

but it does not tell us the truth about anything.

Similarly, the Bible, one of the most

important texts in human history, has connected millions of

people together, but not necessarily by telling them the truth.

When information is in a complete free market, the vast majority

of information becomes fiction, illusion, or lies. This is

because there are three main difficulties with truth.

First of all, telling the truth is

costly. On the other hand, creating fiction is inexpensive.

If you want to write a truthful account

of history, economics, physics, et cetera, you need to

invest time, effort, and money in gathering evidence and

fact-checking.

With fiction, however, you can simply

write whatever you want.

Second, truth is often complex, because reality

itself is complex. Fiction, on the other hand, can be as

simple as you want it to be.

And finally, truth is often painful and unpleasant.

Fiction, on the other hand, can be made as pleasant and

appealing as possible.

Thus, in a completely free information

market, truth would be overwhelmed and buried by the sheer

volume of fiction and illusion.

If we want to get to the truth, we must make

a special effort to repeatedly try to uncover the facts. This is

exactly what has happened with the spread of the internet. The

internet was a completely free marketplace of information.

Therefore, the expectation that the internet

would spread facts and truths, and spread understanding and

consensus among people, quickly proved to be naive.

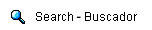

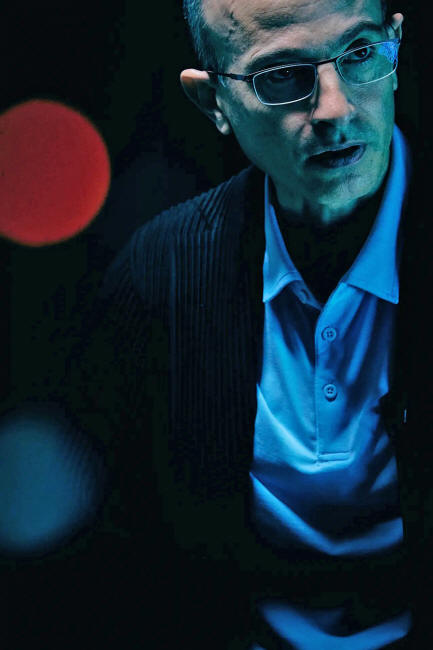

Photograph:

Shintaro Yoshimatsu

In a recent interview with The New Yorker,

Bill Gates said, "I always thought that digital technology

empowers people, but social networking is something completely

different.

We were slow to realize

that. And AI is something completely different as well."

If AI is unprecedented,

what, if anything, can we learn from the past?

There are many things we can learn from history.

First, knowing history helps us understand

what new things AI has brought. Without knowing the history, we

cannot properly understand the novelty of the current situation.

And the most important point about AI is that

it is an agent, not just a tool.

Some people often equate the AI revolution with the printing

revolution, the invention of the written word, or the emergence

of mass media such as radio and television, but this is a

misunderstanding. All previous information technologies were

mere tools in the hands of humans.

Even when the printing press was invented, it

was still humans who wrote the text and decided which books to

print. The printing press itself cannot write anything, nor can

it choose which books to print.

AI, however, is fundamentally different: It is an agent; it can

write its own books and decide which ideas to disseminate. It

can even create entirely new ideas on its own, something that

has never been done before in history.

We humans have never faced a superintelligent

agent before.

Of course, there have been actors in the past. Animals are one

example. However, humans are more intelligent than animals,

especially in the area of connection, in which they are

overwhelmingly superior. In fact, the greatest strength of Homo

sapiens is not its individual capabilities.

On an individual level, I am not stronger

than a chimpanzee, an elephant, or a lion. If a small group, say

10 humans and 10 chimpanzees, were to fight, the chimpanzees

would probably win.

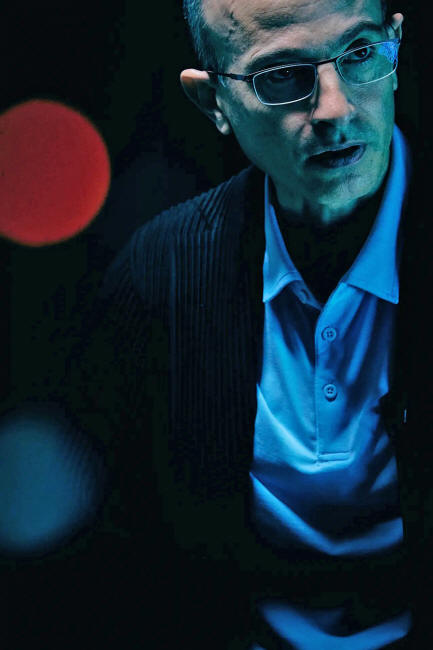

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

So why do humans dominate the planet?

It is because humans can create networks of

thousands, millions, and even billions of people who do not know

each other personally but can cooperate effectively on a huge

scale.

Ten chimpanzees can cooperate closely with

each other, but 1,000 chimpanzees cannot. Humans, on the other

hand, can cooperate not with 1,000 individuals, but with a

million or even a hundred million.

The reason why human beings are able to cooperate on such a

large scale is because we can create and share stories. All

large-scale cooperation is based on a common story. Religion is

the most obvious example, but financial and economic stories are

also good examples.

Money is perhaps the most successful story in

history.

Money is just a story. The bills and coins

themselves have no objective value, but we believe in the same

story about money that connects us and allows us to cooperate.

This ability has given humans an advantage

over chimpanzees, horses, and elephants. These animals cannot

create a story like money.

But AI can. For the first time in history, we share the planet

with beings that can create and network stories better than we

can.

The biggest question facing humanity today

is:

How do we share the planet with this new

superintelligence?

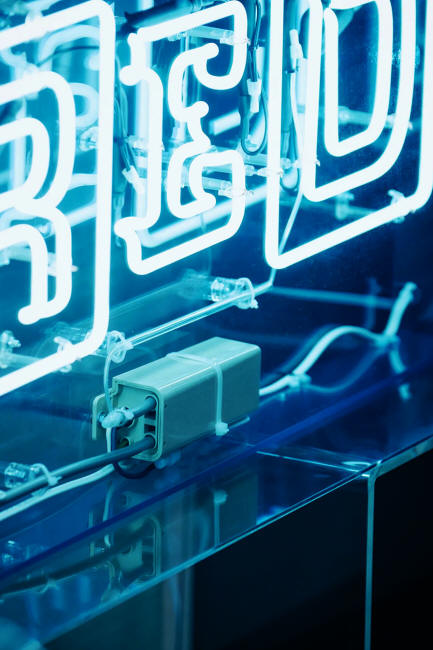

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

How should we think about this new era of

superintelligence?

I think the basic attitude toward the AI revolution is to avoid

extremes.

At one end of the spectrum is the fear that

AI will come along and destroy us all, and at the other end is

optimism that AI will improve health care, improve education,

and create a better world.

What we need is a middle path. First and foremost, we need to

understand the scale of this change. Compared to the AI

revolution we are facing now, all previous revolutions in

history will pale in comparison.

This is because throughout history, when

humans invented something, it was always they who made the

decisions about how to use it to create a new society, a new

economic system, or a new political system.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

Consider, for example, the Industrial

Revolution of the 19th century.

At that time, people invented steam engines,

railroads, and steamships.

Although this revolution transformed the

productive capacity of economies, military capabilities, and

geopolitical situations, and brought about major changes

throughout the world, it was ultimately people who decided how

to create industrial societies.

As a concrete example, in the 1850s, the US commodore Matthew C.

Perry came to Japan on a steamship and forced Japan to accept US

trade terms. As a result, Japan decided: Let's industrialize

like the US.

At that time, there was a big debate in Japan

over whether to industrialize or not, but the debate was only

between people. The steam engine itself did not make any

decision.

This time, however, in building a new society based on AI,

humans are not the only ones making decisions. AI itself may

have the power to come up with new ideas and make decisions.

What if AI had its own money, made its own decisions about how

to spend it, and even started investing it in the stock market?

In that scenario, to understand what is

happening in the financial system, we would need to understand

not only what humans are thinking, but also what AI is thinking.

Furthermore, AI has the potential to generate

ideas that are completely incomprehensible to us.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

I would like to clarify what you think about

the singularity, because I often see you spoken of as being

"anti-singularity."

However, in your new book,

you point out that AI is more creative than humans and that it

is also superior to humans in terms of emotional intelligence.

I was particularly struck by your statement that the root of all

these revolutions is the computer itself, of which the internet

and AI are only derivatives.

WIRED just published a

series on quantum computers, so to take this as an example: If

we are given a quantum leap in computing power in the future, do

you think that a singularity, a reordering of the world order by

superintelligence, is inevitable?

That depends on how you define singularity.

As I understand it, singularity is the point

at which we no longer understand what is happening out there. It

is the point at which our imagination and understanding cannot

keep up. And we may be very close to that point.

Even without a quantum computer or fully-fledged artificial

general intelligence - that is, AI that can rival the

capabilities of a human - the level of AI that exists today may

be enough to cause it.

People often think of the AI revolution in

terms of one giant AI coming along and creating new inventions

and changes, but we should rather think in terms of networks.

What would happen if millions or tens of

millions of advanced AIs were networked together to bring about

major changes in economics, military, culture, and politics?

The network will create a completely

different world that we will never understand. For me,

singularity is precisely that point - the point at which our

ability to understand the world, and even our own lives, will be

overwhelmed.

If you ask me if I am for or against singularity, first and

foremost I would say that I am just trying to get a clear

understanding of what is going on right now. People often want

to immediately judge things as good or bad, but the first thing

to do is to take a closer look at the situation.

Looking back over the past 30 years,

technology has done some very good things and some very bad

things. It has not been a clear-cut "just good" or "just bad"

thing.

This will probably be the same in the future.

The one obvious difference in the future, however, is that when

we no longer understand the world, we will no longer control our

future. We will then be in the same position as animals.

We will be like the horse or the elephant

that does not understand what is happening in the world. Horses

and elephants cannot understand that human political and

financial systems control their destiny.

The same thing can happen to us humans.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

You've said, "Everyone talks about the

'post-truth' era, but was there ever a 'truth' era in history?"

Could you explain what you

mean by this?

We used to understand the world a little better, because it was

humans who managed the world, and it was a network of humans.

Of course, it was always difficult to

understand how the whole network worked, but at least as a human

being myself, I could understand kings, emperors, and high

priests.

They were human beings just like me. When the

king made a decision, I could understand it to some extent,

because all the members of the information network were human

beings.

But now that AI is becoming a major member of

the information network, it is becoming increasingly difficult

to understand the important decisions that shape our world.

Perhaps the most important example is finance. Throughout

history, humans have invented increasingly sophisticated

financial mechanisms. Money is one such example, as are stocks

and bonds. Interest is another financial invention.

But what is the purpose of inventing these

financial mechanisms?

It is not the same as inventing the wheel or

the automobile, nor is it the same as developing a new kind of

rice that can be eaten.

The purpose of inventing finance, then, is to create trust and

connection between people. Money enables cooperation between you

and me. You grow rice and I pay you.

Then you give me the rice and I can eat it.

Even though we do not know each other personally, we both trust

money. Good money builds trust between people.

Finance has built a network of trust and cooperation that

connects millions of people. And until now, it was still

possible for humans to understand this financial network.

This is because all financial mechanisms

needed to be humanly understandable. It makes no sense to invent

a financial mechanism that humans cannot understand, because it

cannot create trust.

But AI may invent entirely new financial mechanisms that are far

more complex than interest, bonds, or stocks. They will be

mathematically extremely complex and incomprehensible to humans.

AI itself, on the other hand, can understand

them. The result will be a financial network where AIs trust

each other and communicate with each other, and humans will not

understand what is happening.

We will lose control of the financial system

at this point, and everything that depends on it.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

So AI can build networks of trust that we

can't understand. Such incomprehensible things are known as "hyperobjects."

For example, global climate

change is something that humans cannot fully grasp the

mechanisms or full picture of, but we know it will have a

tremendous impact and that we therefore must confront and adapt

to it.

AI is another hyperobject

that humanity will have to deal with in this century. In your

book, you cite human flexibility as one of the things needed to

deal with big challenges.

But what does it actually

mean for humanity to deal with hyperobjects?

Ideally, we would trust AI to help us deal with these

hyperobjects - realities that are so complex that they are

beyond our comprehension.

But perhaps the biggest question in the

development of AI is: How do we make AI, which can be more

intelligent than humans, trustworthy? We do not have the answer

to that question.

I believe the biggest paradox in the AI revolution is the

paradox of trust - that is, that we are now rushing to develop

superintelligent AI that we do not fully trust. We understand

that there are many risks.

Rationally, it would be wise to slow down the

pace of development, invest more in safety, and create safety

mechanisms first to make sure that superintelligent AIs do not

escape our control or behave in ways that are harmful to humans.

However, the opposite is actually happening today.

We are in the midst of an accelerating AI

race. Various companies and nations are racing at breakneck

speed to develop more powerful AIs. Meanwhile, little investment

has been made to ensure that AI is secure.

Ask the entrepreneurs, businesspeople, and government leaders

who are leading this AI revolution, "Why the rush?" and nearly

all of them answer:

"We know it's risky, for sure. We know

it's dangerous.

We understand that it would be wiser to

go slower and invest in safety. But we cannot trust our

human competitors.

If other companies and countries

accelerate their development of AI while we are trying to

slow it down and make it safer, they will develop

superintelligence first and dominate the world.

So we have no choice but to move forward

as fast as possible to stay ahead of the unreliable

competition."

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

But then I asked those responsible for AI a second question:

"Do you think we can trust the

superintelligence you are developing?"

Their the answer was:

"Yes."

This is almost insane. People who don't even

trust other humans somehow think they can trust this alien AI.

We have thousands of years of experience with humans. We

understand human psychology and politics. We understand the

human desire for power, but we also have some understanding of

how to limit that power and build trust among humans.

In fact, over the past few thousand years,

humans have developed quite a lot of trust. 100,000 years ago,

humans lived in small groups of a few dozen people and could not

trust outsiders.

Today, however, we have huge nations, trade

networks that extend around the world, and hundreds of millions,

even billions, of people who trust each other to some extent.

We know that AI is a doer, that it makes its own decisions,

creates new ideas, sets new goals, creates tricks and lies that

humans do not understand, and may pursue alien goals beyond our

comprehension. We have many reasons to be suspicious of AI.

We have no experience with AI, and we do not

know how to trust it.

I think it is a huge mistake for people to assume that they can

trust AI when they do not trust each other.

The safest way to develop superintelligence

is to first strengthen trust between humans, and then cooperate

with each other to develop superintelligence in a safe manner.

But what we are doing now is exactly the opposite.

Instead, all efforts are being directed

toward developing a superintelligence.

Some WIRED readers with a libertarian mindset

may have more faith in superintelligence than in humans, because

humans have been fighting each other for most of our history.

You say that we now have

large networks of trust, such as nations and large corporations,

but how successful are we at building such networks, and will

they continue to fail?

It depends on the standard of expectations we have.

If we look back and compare humanity today to

100,000 years ago, when we were hunter-gatherers living in small

herds of a few dozen people, we have built an astonishingly

large network of trust.

We have a system in which hundreds of

millions of people cooperate with each other on a daily basis.

Libertarians often take these mechanisms for granted and refuse

to consider where they come from. For example, you have

electricity and drinking water in your home.

When you go to the bathroom and flush the

water, the sewage goes into a huge sewage system. That system is

created and maintained by the state.

But in the libertarian mindset, it is easy to

take for granted that you just use the toilet and flush the

water and no one needs to maintain it. But of course, someone

needs to.

There really is no such thing as a perfect free market. In

addition to competition, there always needs to be some sort of

system of trust.

Certain things can be successfully created by

competition in a free market, however, there are some services

and necessities that cannot be sustained by market competition

alone. Justice is one example.

Imagine a perfect free market. Suppose I enter into a business

contract with you, and I break that contract. So we go to court

and ask the judge to make a decision. But what if I had bribed

the judge? Suddenly you can't trust the free market.

You would not tolerate the judge taking the

side of the person who paid the most bribes. If justice were to

be traded in a completely free market, justice itself would

collapse and people would no longer trust each other.

The trust to honor contracts and promises

would disappear, and there would be no system to enforce them.

Therefore, any competition always requires some structure of

trust. In my book, I use the example of the World Cup of soccer.

You have teams from different countries

competing against each other, but in order for competition to

take place, there must first be agreement on a common set of

rules. If Japan had its own rules and Germany had another set of

rules, there would be no competition.

In other words,

even competition requires a foundation of

common trust and agreement.

Otherwise, order itself will collapse.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

In Nexus, you note that the mass media made

mass democracy possible - in other words, that information

technology and the development of democratic institutions are

correlated.

If so, in addition to the

negative possibilities of populism and totalitarianism, what

opportunities for positive change in democracies are possible?

In social media, for example, fake news, disinformation, and

conspiracy theories are deliberately spread to destroy trust

among people.

But algorithms are not necessarily the

spreaders of fake news and conspiracy theories. Many have

achieved this simply because they were designed to do so.

The purpose the algorithms of Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok is

to maximize user engagement. The easiest way to do this, it was

discovered after much trial and error, was to spread information

that fueled people's anger, hatred, and desire.

This is because when people are angry, they

are more inclined to pursue the information and spread it to

others, resulting in increased engagement.

But what if we gave the algorithm a different purpose? For

example, if you give it a purpose such as increasing trust among

people or increasing truthfulness, the algorithm will never

spread fake news.

On the contrary, it will help build a better

society, a better democratic society.

Another important point is that democracy should be a dialogue

between human beings. In order to have a dialogue, you need to

know and trust that you are dealing with a human being.

But with social media and the internet, it is

increasingly difficult to know whether the information you are

reading is really written and disseminated by humans or just

bots.

This destroys trust between humans and makes

democracy very difficult.

To address this, we could have regulations and laws prohibiting

bots and AI from pretending to be human. I don't think AI itself

should be banned at all; AI and bots are welcome to interact

with us, but only if they make it clear that they are AI and not

human.

When we see information on Twitter, we need

to know whether it is being spread by a human or a bot.

Some people may say,

"Isn't that a violation of freedom of

expression?"

But bots do not have freedom of expression.

While I firmly oppose censorship of human

expression, this does not protect the expression of bots.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

Will we become smarter or reach better

conclusions by discussing topics with artificial intelligence in

the near future?

Will we see the kind of

creativity that humans can't even conceive of, as in the case of

AlphaGo, which you also describe in your new book, in classroom

discussions, for example?

Of course it can happen.

On the one hand, AI can be very creative and

come up with ideas that we would never have thought of. But at

the same time, AI can also manipulate us by feeding us vast

amounts of junk and misleading information.

The key point is that we humans are stakeholders in society. As

I mentioned earlier with the example of the sewage system, we

have a body.

If the sewage system collapses, we become

sick, spreading diseases such as dysentery and cholera, and in

the worst case, we die. But that is not a threat at all to AI,

which does not care if the sewage system collapses, because it

will not get sick or die.

When human citizens debate, for example,

whether to allocate money to a government agency to manage a

sewage system, there is an obvious vested interest.

So while AI can come up with some very novel

and imaginative ideas for sewage systems, we must always

remember that AI is not human or even organic to begin with.

It is easy to forget that we have bodies, especially when we are

discussing cyberspace.

What makes AI different from humans is not

only that its imagination and way of thinking, which are alien,

but also that its body itself is completely different from ours.

Ultimately, AI is also a physical being; it

does not exist in some purely mental space, but in a network of

computers and servers.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

What is the most important thing to consider

when thinking about the future?

I think there are two important issues.

One is the issue of trust, which has been

the subject of much discussion up to this point.

We are now

in a situation where trust between human beings is at stake.

This is the greatest danger. If we can

strengthen trust between humans, we will be better able to

cope with the AI revolution.

The second is the threat of being completely manipulated or

misdirected by AI.

In the early internet days, the primary

metaphor for technology was the Web. The World Wide Web was

envisioned as a spiderweb-like network connecting people to

each other.

Today, however, the primary metaphor is the

cocoon.

People are increasingly living in individual

cocoons of information. People are bombarded with so much

information that they are blind to the reality around them.

People are trapped in different information cocoons.

For the first time in history, a nonhuman

entity, an AI, is able to create such a cocoon of information.

Throughout history, people have lived in a human cultural

cocoon. Poetry, legends, myths, theater, architecture, tools,

cuisine, ideology, money, and all the other cultural products

that have shaped our world have all come from the human mind. In

the future, however, many of these cultural products will come

from nonhuman intelligence.

Our poems, videos, ideologies, and money will

come from nonhuman intelligence. We may be trapped in such an

alien world, out of touch with reality.

This is a fear that humans have held deep in

their hearts for thousands of years. Now, more than ever, this

fear has become real and dangerous.

For example, Buddhism speaks of the concept of māyā - illusion,

hallucination.

With the advent of AI, it may be even more

difficult to escape from this world of illusion than before. AI

is capable of flooding us with new illusions, illusions that do

not even originate in the human intellect or imagination.

We will find it very difficult to even

comprehend the illusions.

Photograph: Shintaro

Yoshimatsu

You mention "self-correcting mechanisms" as an

important function in maintaining democracy. I think this is

also an important function to get out of the cocoon and in

contact with reality.

On the other hand, in your

book, you write that the performance of the human race since the

Industrial Revolution should be graded as "C minus," or just

barely acceptable.

If that is the case, then

surely we cannot expect much from the human race in the coming

AI revolution?

When a new technology appears, it is not necessarily bad in

itself, but people do not yet know how to use it beneficially.

The reason why they don't know is that we

don't have a model for it.

When the Industrial Revolution took place in the 19th century,

no one had a model for how to build a "good industrial society"

or how to use technologies such as steam engines, railroads, and

telegraphs for the benefit of humanity. Therefore, people

experimented in various ways.

Some of these experiments, such as the

creation of modern imperialism and totalitarian states, had

disastrous results.

This is not to say that AI itself is bad or harmful. The real

problem is that we do not have a historical model for building

an AI society.

Therefore, we will have to repeat

experiments.

Moreover, AI itself will now make its own

decisions and conduct its own experiments. And some of these

experiments may have terrible results.

That is why we need a self-correcting mechanism - a mechanism

that can detect and correct errors before something fatal

happens. But this is not something that can be tested in a

laboratory before introducing AI technology to the world.

It is impossible to simulate history in a

laboratory.

For example, let's consider the railroad being invented.

In a laboratory, people were able to see if steam engines would

explode due to a malfunction. But no one could simulate the

changes they would bring to the economic and political situation

when the rail network spread out over tens of thousands of

kilometers.

The same is true of AI.

No matter how many times we experiment with

AI in the laboratory, it will be impossible to predict what will

happen when millions of superintelligences are unleashed on the

real world and begin to change the economic, political, and

social landscape.

Almost certainly, there will be major

mistakes.

That is why we should proceed more carefully

and more slowly. We must allow ourselves time to adapt, time to

discover, and correct our mistakes.