|

She is also frequently illustrated with two tails.

The image of Melusine is

so famous and enduring that, perhaps without knowing her by name, we

still recognize her image today as the logo for Starbucks Coffee.

The Starbucks Logo Melusine and her two tails

Deriv (CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Vouvant, paintings of

her and her sons decorate the "Tour Melusine," the ruins of a

Lusignan castle guarding the banks of the River Mère, where visitors

of the tower can lunch at the Cafe Melusine nearby.

(Public

Domain)

Her name derives from Mère Lusine ("Mother of the Lusignans"), connecting her with Cyprus, where the French Lusignan royal house that ruled from 1192 to 1489 claimed to be her descendants.

The legend of Melusine, therefore, is related to the territorial and dynastic expansion of her descendants beyond Lusignan across the Mediterranean to distant Armenia during the crusades (1095 - 1291).

The lady's name was Pressyne.

Elynas persuaded her to marry him and she agreed.

The couple lived happily for some time until Pressyne gave birth to triplets.

When, as one would expect

to happen in these stories, her husband broke his promise, Pressyne

left the kingdom, together with her three daughters, and traveled to

the lost Isle of Avalon where her daughters - Melusine,

Melior and Palatyne - would grow up.

The woman took her children to the lost Isle of Avalon

(CC BY 2.0)

After hearing of their father's broken promise, Melusine sought revenge.

She rallied her sisters and the three sisters captured Elynas and trapped him in a mountain. When she heard what her daughters have done, Pressyne punished them for their disrespect to their father.

She condemned Melusine to

take the form of a fish from the waist down every Saturday. In other

versions of the legend, Melusine was condemned to take on the form

of a serpent on Saturdays.

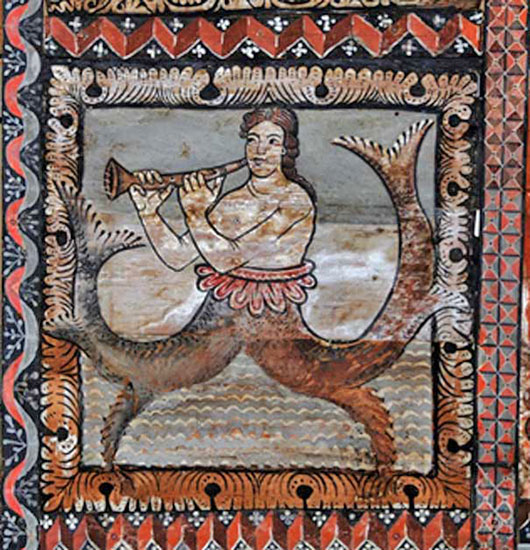

Melusine with a horn, wooden panel from St.Martin's Church in Zillis, Switzerland (CC BY 2.0)

The flight of Melusine as a serpent, Manuscript 4028, Nuremberg, Nationalmuseum, 1468

Some time later, history

repeated itself when, while out hunting in the forests of the

Ardennes, Raymondin, Lord of Forez in Poitou, a poor but

noble gentleman, met the beautiful Melusine who was sitting beside a

fountain in a glimmering white dress.

Melusine agreed to marry

Raymondin on the condition he promises not to attempt to see her on

Saturdays when she would go into seclusion.

This connection between

Melusine, with her fairy heritage, and the growing prosperity and

fertility of the region of Poitou may have been one of the

foundations of our modern construct of the benevolent fairy

godmother.

All of Melusine's sons would later become kings and tyrants.

Through the heritage of the sons of Melusine, the elements of mythology are blended with history to align the supernatural founder of the dynasty of Lusignan with the aspirations of late feudal society.

The practice of claiming descent from a supernatural being, even from gods and goddesses, has already been done by many leaders throughout the world, from the ancient Roman Emperor Augustus who claimed to be descended from the war god Mars to the ancient emperors of China who claimed to be descended from a divine dragon.

By weaving the mythology of the supernatural from the folklore tradition into the royal lineage, the myths and the powers of Melusine can therefore be ascribed to the family name to add glamour and legitimacy.

'Die

schöne Melusine' 1844

Curiosity overcame

Raymondin and, one Saturday, he spied on his wife through the

keyhole. He saw with his own eyes how the lower part of Melusine's

body took on animal qualities.

However, one day in a

heated argument, Raymondin blamed her for their children's

deformities and called her a monster. Despised by her husband, the

heartbroken Melusine developed wings and jumped through the window,

leaving a human footprint on the stone.

As her sons grew older, Melusine would still return periodically to keep watch over her sons, flying around the castle crying mournfully. She was never far away from her beloved family as she is sometimes heard wailing at night, especially when the castle changes leadership.

Her lineage continues in

many parts of Europe and the Mediterranean as her sons became kings

of new lands.

The legend says that, every seven years, Melusine appears in human form in the upper world above the cliffs, asking the passers-by to redeem her.

If this does not happen, the white figure soars over the city crying,

Melusine's secret discovered,

from Le Roman de Mélusine. c. 1450

Melusine appeared to him in the form of a beautiful maiden and asked him to redeem her. She told him that it would be a difficult, but not impossible, task.

However, she said that he should not attempt it if he thought that he might not succeed, because if he failed she would sink three times deeper into the earth.

While she was speaking, a

mighty rumbling sound arose from around the cliffs, causing the

soldier to fear that they were about to collapse.

After he had done this

nine times, on the tenth evening Melusine herself would appear to

him in the form of a fiery serpent with a key in her mouth. He would

have to take the key from her mouth and throw it into the Alzette

River, thus accomplishing her redemption.

Returning to his quarters, the soldier heard such howling and screeching from the cliffs that he thought all the wild animals were fighting one another in the air. However, no one else heard the noise.

The howling was Melusine's cry of anguish and she has not been redeemed even to this day.

In classical mythology, the Sirens - famed for luring sailors to their death with their irresistible song - were usually taken to be a half-woman/half-bird.

However, the Sirens' association with the sea were highlighted, especially in the Christian era, by depicting them as half-woman/half-fish as fish also symbolize the lower realm.

The use of the image of Melusine is usually considered as a symbol of eloquence in its positive aspect. This is presumably in deference to the seductive song of the Sirens centuries before.

The connection between Melusine and fertility is sometimes underlined by the bulging female abdomen that often features in the representations of her.

The two tails, which are

usually shown folded towards the mermaid's head, are transformations

of the legs of the earth goddess which are spread either in sexual

relations or in childbirth.

With one pope in Rome and

another in Avignon from 1378 to 1415, the religious stability of

Europe at the time was also threatened.

In 1316, both Louis X and his infant son died, leaving his country without a male heir and only his four-year-old daughter, Joan, to succeed him.

Twelve years later, Charles IV died childless, therefore ending the senior branch of the Capetian line.

Charles' closest male

relative, King Edward III of England, the son of Charles'

sister, created a pretext for the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453),

which would destroy much of the countryside of Western France for

the next 116 years.

With this in mind, the

French, apart from studying their origins more closely, also used

symbols to represent the idea of France, such as the three lilies,

the winged deer, and the Tree in the Garden of Paradise which

represents the French territory.

L'Arcas writthevêque traced his ancestry to the Lusignans, an aristocratic family with landholdings in western Poitou.

This genealogical romance were meant to be a historical account and describes the founding of the Lusignan family by the main character, Melusine, a matriarchal fairy who built many towns and castles in the region.

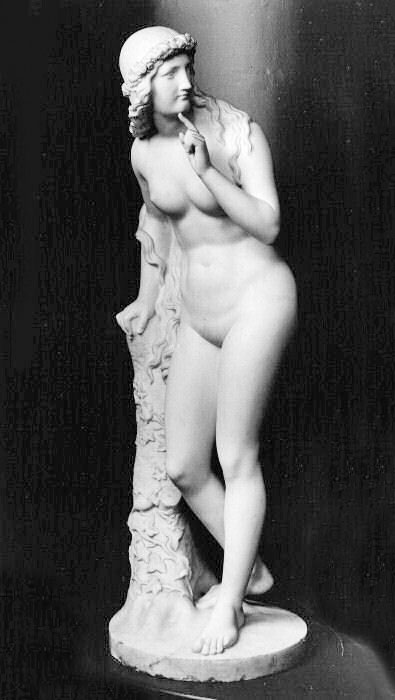

19th Century German Sculture entitled " Melusine" in the Russell Cotes Museum and Art Gallery,

Bournemouth, Dorset, England

|