|

by Justin D. Collins

June 30,

2023

from

ClassicalWisdom Website

Italian

version

Ulysses

and the Sirens,

by J.

W. Waterhouse, 1891

The most well-known episodes in Homer's

Odyssey are the adventures

described in Books 9-12.

Full of one-eyed

giants, amorous goddesses and narrow escapes, they

are considered the most memorable and thus most likely to be

included in collections of excerpts.

They have received so

much attention that it is often forgotten that they make up only a

small part of the epic - an epic that is far more concerned with the

homecoming of Odysseus than with his wanderings.

These stories are told in the first person by Odysseus himself.

Given what we know of his

character from both

the Iliad and

the Odyssey, Odysseus does not

hesitate to deceive when circumstances allow. Thus, we should

carefully consider the veracity of his tales.

After all, Homer calls

Odysseus a "man of twists and turns," and we expect him to live up

to the description.

Odysseus' reputation thus begs the question:

Is it possible that

the tales are not meant to be taken as relating "real" events?

In other words, could

it be that Odysseus did not actually have these adventures, or

at least did not have them as he relates them?

The stories Odysseus

tells have a fairy-tale, magical quality about them that is

different from the rest of the Odyssey.

The unreal, dream-like

world of monsters and enchantresses is distinct from the more

realistic, historical world of

Ithaca and the Greek mainland.

Further, Odysseus'

stories interrupt the forward-moving time scheme of the poem; they

have the character of flashbacks, contributing to the feeling of

"unreality."

It should be noted that

Odysseus is speaking to an audience, the

Phaeacians, from whom he is in

desperate need of aid. Certainly, Odysseus is not above using his

stories to sway them according to his desire.

Indeed, Odysseus may have been catering to King Alcinous, who

expressly asks to hear of his guest's exciting travels:

But come, my friend,

tell us your own story now, and tell it truly.

Where have your

rovings forced you?

What lands of men

have you seen, what sturdy towns, what men themselves?

Who were wild,

savage, lawless?

Who were friendly to

strangers, god-fearing men?

Tell me, why do you

weep and grieve so sorely when you hear the fate of the Argives,

hear the fall of Troy?

That is the god's

work, spinning threads of death through the lives of mortal men,

and all to make a song for those to come...

(Odyssey,

VIII.640-650)

Odysseus' tales

conveniently sound these same themes:

the savage, the

hospitable, the pious, the lawless, and death...

Odysseus is on next after

the great bard, Demodocus, has regaled the assembly with his

songs, one of which was suggested by Odysseus himself and glorified

his exploits at Troy.

Odysseus has a big act to follow and, as he is about to announce his

identity as the Odysseus about whom the Phaeacians have just heard

so much, it would obviously not do to disappoint.

Homer here refer

to Odysseus as,

"the great teller of

tales"...

Both the reader and the

Phaeacians are expecting something big, and Odysseus delivers.

The Phaeacians respond

well to the stories, hanging on Odysseus' every word and showering

him with even more gifts.

Would not someone of

Odysseus' resourcefulness be expected to know how they would

respond and be able to tailor his adventures to the tastes of

his audience?

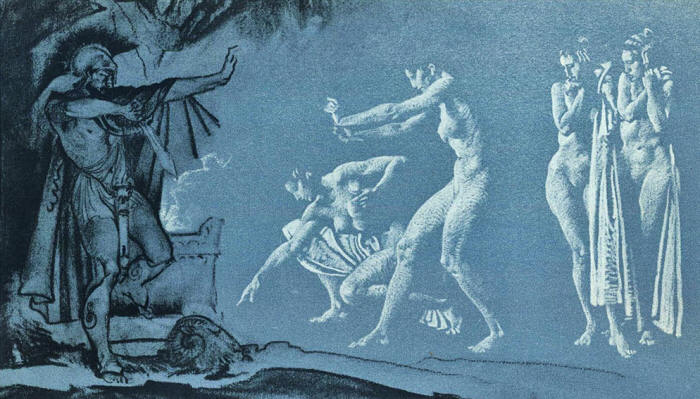

Odysseus before

Alcinous King of the Phaeacians,

by

August Malmstrom, 1853

The Phaeacians appear to be a relatively innocent people.

They are no match for

devious Odysseus...

King Alcinous goes

so far as to praise Odysseus for his honesty:

'Ah Odysseus,'

Alcinous replied, 'one look at you and we know that you are no

one who would cheat us - no fraud, such as the dark soil breeds

and spreads across the face of the earth these days.

Crowds of vagabonds

frame their lies so tightly that none can test them. But you,

what grace you give your words, and what good sense within!'

(Odyssey,

XI. 410-415)

The King's words must

come off as ironic to any reader or listener aware that wiliness is

the epitome of the Odyssean character.

Homer, being

well-acquainted with the Odyssean character, already knows what we

will think about Alcinous' remark.

Later in the poem, when Odysseus reached Ithaca, it is amply

demonstrated that he is a consummate liar. Upon arriving, he spins a

series of bold-faced deceptions, commonly referred to as the "Cretan

lie."

At first, he tries to deceive a shepherd boy, who turns out to be

Athena in disguise...

Athena,

attributed to Rembrandt,

17th

century

She, of course, sees through him:

"Any man - any god

who met you - would have to be some champion lying cheat to get

past you for all-round craft and guile!

You terrible man,

foxy, ingenious, never tired of twists and tricks - so not even

here, on native soil, would you give up those wily tales that

warm the cockles of your heart!"

What better candidate

could there be for these "wily tales" than the stories Odysseus so

recently told to the Phaeacians?

Homer has left us many textual clues which suggest that,

the stories Odysseus

tells the Phaeacians are not meant to be taken as having

"really" happened...

Such a view of these

stories should encourage us always to be careful readers.

We may encounter

unexpected "twists and turns" that reveal more and deeper levels of

art and meaning, inspiring us to read old books with fresh eyes.

Just as the adventures described in

Books 9 (IX) to 12 (XII) of the Odyssey

are often the most-remembered episodes due to their fantastic

character, so Odysseus' account of the underworld is

one of his most striking.

But did it "really"

happen?

Are we meant to

believe that, within the horizon of the poem, Odysseus actually

travelled to the underworld - or is he telling another tall

tale?

Of all the stories

Odysseus tells the Phaeacians, his account of the underworld

is the only one to contain an interruption, emphasizing that this is

a story being told to an audience.

Odysseus pauses to

suggest that it may be time to break off story-telling and go to

sleep.

But King Alcinous

urges him to continue:

"The night's still

young, I'd say the night is endless.

For us in the palace

now, it's hardly time for sleep. Keep telling us your adventures

- they are wonderful."

Odysseus is spinning a

yarn to please a king from whom he has much to gain, and the King

wants more.

Alcinous prompts Odysseus by asking if he saw any heroes in Hades:

"But come now, tell

me truly: your godlike comrades - did you see any heroes down in

the House of Death, any who sailed with you and met their doom

at Troy?"

His host and benefactor

has indicated a subject he would like to hear about, and Odysseus

obliges in style, dropping a great many well-known names to help set

the stage.

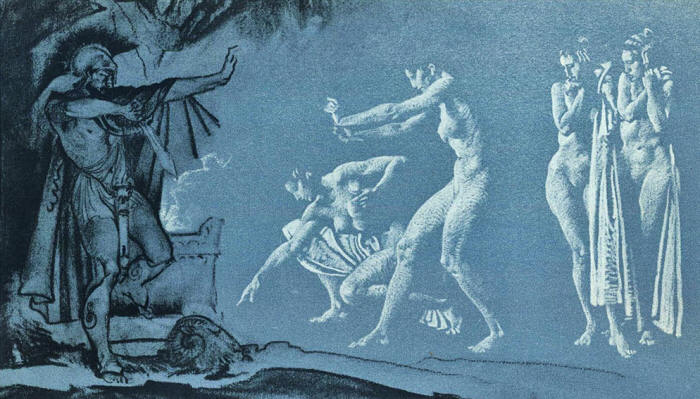

Odysseus in Hades

by

Russell Flint, 1924

But if this is theater - if Odysseus is not relating something that

"really" happened - what are we to make of this tale?

The story of the underworld can be seen as an

expression of the hopes, fears, and doubts of a man who has been

away from home for a very long time.

These feelings are the

material around which Odysseus builds his story.

The driving themes are

laid out when he questions his mother in the underworld:

'But tell me about

yourself and spare me nothing.

What form of death

overcame you, what laid you low, some long slow illness? Or did

Artemis showering arrows come with her painless shafts and bring

you down?

Tell me of father,

tell of the son I left behind: do my royal rights still lie in

their safekeeping? Or does some stranger hold the throne by now

because men think that I'll come home no more?

Please, tell me about

my wife, her turn of mind, her thoughts... still standing fast

beside our son, still guarding our great estates, secure as ever

now?

Or has she wed some

other countryman at last, the finest prince among them?'

(Odyssey,

XI.193-205)

Odysseus

attempting to embrace

the ghost of his mother

in

the Underworld,

by Jan Styka, 1901

Anyone in Odysseus' shoes would wonder if their aged parents were

still living. The other concerns, also very natural, are reflected

not only in these questions, but also in his conversations with the

other shades.

These concerns can be

characterized as follows:

1) The faithfulness

of his wife

2) The fortunes of his son

3) The honor of his house...

In the underworld,

Odysseus is first confronted with a great crowd of wives and

daughters of princes, whom he interviews one by one, reflecting his

anxiety for the purity and success of the household.

These women represent the

theme of womanhood - some are faithful, some treacherous

(unfaithfulness to the marriage bed receives much attention).

His conversations with dead heroes reflect the same

anxiety.

Agamemnon tells

the awful story of how he and his men were slaughtered through the

machinations of a treacherous wife and the lover she took in his

absence.

But Odysseus reassures himself about Penelope's character

using Agamemnon's voice:

"Not that you,

Odysseus will be murdered by your wife. She's much too steady,

her feelings run too deep, Icarius' daughter Penelope, that wise

woman."

Yet doubt still remains,

as is evident the circumspect way he deals with her upon his

homecoming.

Agamemnon also enquires about his son, Orestes. Odysseus must

be wondering what kind of man his own son Telemachus has

become, and how he is faring.

Odysseus' words about

Orestes could just as truly be spoken of his own son:

"I know nothing,

whether he's dead or alive."

Achilles also asks after

the fortunes of his son.

In Odysseus's response we

may see his hopes for Telemachus - that he will take his place among

great men, proficient in feats of war and good counsel.

The Shade of Tiresias

Appearing to Odysseus

during

the Sacrifice

(Book

XI of the Odyssey),

by

Johann Heinrich Füssli (c. 1780-85)

Achilles brings up another concern likely to resonate with Odysseus:

the honor of his

father and house without him there to defend them.

Odysseus has already

asked his mother about such things, and in Achilles' comments we

catch a glimpse of the thoughts of a son who returned to find his

father abused and the honor of his house diminished:

"Oh to arrive at

father's house - the man I was, for one brief day - I'd make my

fury and my hands, invincible hands, a thing of terror to all

those men who abuse the king with force and wrest away his

honor!"

The story of

Odysseus' journey to the underworld underlines our common

humanity and the ever-lasting value of classical works.

Thousands of years after

its composition, readers can still identify with the hopes and

fears of the hero of the Odyssey...

|