|

by Jan Bartek

April

27, 2021

from

AncientPages Website

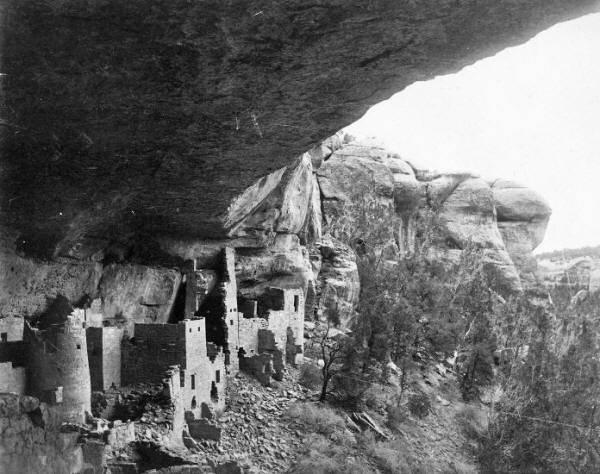

Chaco Canyon:

Chaco Culture National Historical Park,

New Mexico.

Credit: Dot Nielsen / Flickr.

Archeologists have long

speculated about the causes of occasional upheavals in the

pre-Spanish societies created by the ancestors of contemporary

Pueblo peoples.

These Ancestral Pueblo communities once occupied the

Four Corners area of the U.S. from

500 to 1300 where today Colorado borders Utah, Arizona, and New

Mexico.

While these communities were often stable for many decades, they

experienced several disruptive social transformations before leaving

the area in the late 1200s.

When more precise

measurements indicated that droughts coincided with these

transformations, many archeologists decided that these climate

challenges were their primary cause.

However, a new study reveals the ancient Pueblo societies struggle

with social tensions, which contributed to their downfall.

Drought is often blamed for the periodic disruptions of these Pueblo

societies, but climate problems alone were not enough to end periods

of ancient Pueblo development in the southwestern United States.

Archaeologists have found evidence that,

slowly accumulating social

tension likely played a substantial role in three dramatic upheavals

in Pueblo development.

The findings, detailed in an article in the

Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences (Loss

of Resilience preceded Transformations of pre-Hispanic Pueblo

Societies), showed that Pueblo farmers often

persevered through droughts, but when social tensions were

increasing, even modest droughts could spell the end of an era of

development.

"Societies that are

cohesive can often find ways to overcome climate challenges,"

said Tim Kohler, a Washington State University archeologist and

corresponding author on the study.

"But societies that are riven by internal social dynamics of any

sort - which could be wealth differences, racial disparities or

other divisions - are fragile because of those factors.

Then climate

challenges can easily become very serious."

In this study, Tim

Kohler collaborated with complexity scientists from

Wageningen University in The Netherlands, led by Marten

Scheffer, who have shown that loss of resilience in a system

approaching a tipping point can be detected through subtle changes

in fluctuation patterns.

"Those warning

signals turn out to be strikingly universal," said Scheffer,

first author on the study.

"They are based on

the fact that slowing down of recovery from small perturbations

signals loss of resilience."

Other research has found

signs of such "critical slowing down" in systems as diverse as the

human brain, tropical rainforests and ice caps as they approach

critical transitions.

"When we saw the

amazingly detailed data assembled by Kohler's team, we thought

this would be the ideal case to see if our indicators might

detect when societies become unstable - something quite relevant

in the current social context," Scheffer said.

The research used

tree-ring analyses of wood beams used for construction, which

provided a time series of estimated tree-cutting activity spanning

many centuries.

"This record is like

a social thermometer," said Kohler, who is also affiliated with

the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Colorado and the Santa

Fe Institute in New Mexico.

"Tree cutting and

construction are vital components of these societies. Any

deviation from normal tells you something is going on."

They found that weakened

recovery from interruptions in construction activity preceded three

major transformations of Pueblo societies.

These slow-downs were

different than other interruptions, which showed quick returns

to normal in the following years...

The archeologists also

noted increased signs of violence at the same time, confirming that

tension had likely increased and that societies were nearing a

tipping point.

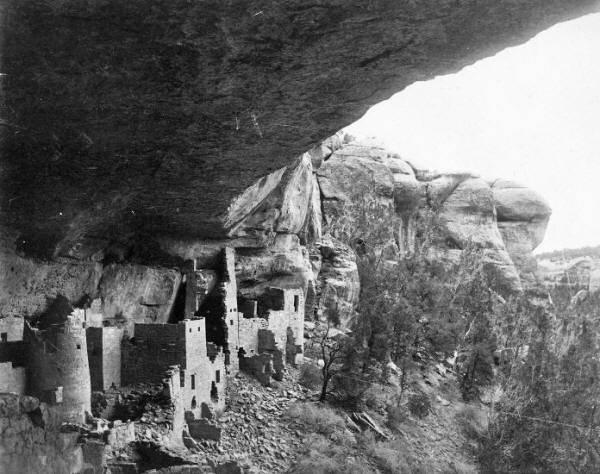

Drought is often blamed for the periodic disruptions

of

ancient Pueblo societies of the U.S. Southwest,

but in

a study with potential implications for the modern world,

archaeologists found evidence that slowly accumulating

social

tension likely played a substantial role in three dramatic upheavals

in

Pueblo development.

The

findings show that Pueblo farmers often persevered

through

droughts, but when social tensions were increasing,

even

modest droughts could spell the end

of an

era of development.

Credit:

Mesa Verde National Park,

MEVE

11084

This happened at the end of the period known as the

Basketmaker

III, around the year 700, as well as near the ends of the

periods called Pueblo I and Pueblo II, around 900 and

1140 respectively.

Near the end of each

period, there was also evidence of drought.

The findings indicate

that it was the two factors together - social fragility and

drought - that spelled trouble for these societies.

Social fragility was not

at play, however, at the end of the Pueblo III period in the

late 1200s when Pueblo farmers left the Four Corners with most

moving far south.

This study supports the

theory that it was a combination of drought and

conflict with outside groups that spurred the Pueblo

peoples to leave.

Kohler said we can still learn from what happens when climate

challenges and social problems coincide.

"Today we face

multiple social problems including

rising wealth inequality along

with deep political and racial divisions, just as climate change

is no longer theoretical," Kohler said.

"If we're not ready

to face the challenges of changing climate as a cohesive

society, there will be real trouble."

|