|

by

Liz Kimbrough

December 08,

2020

from

MongaBay Website

Italian version

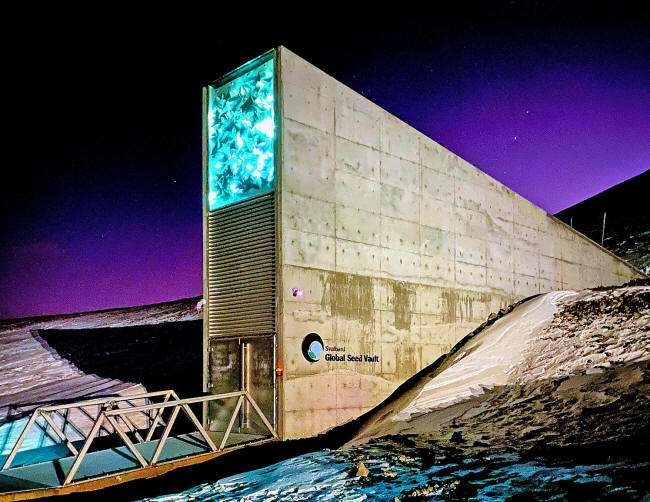

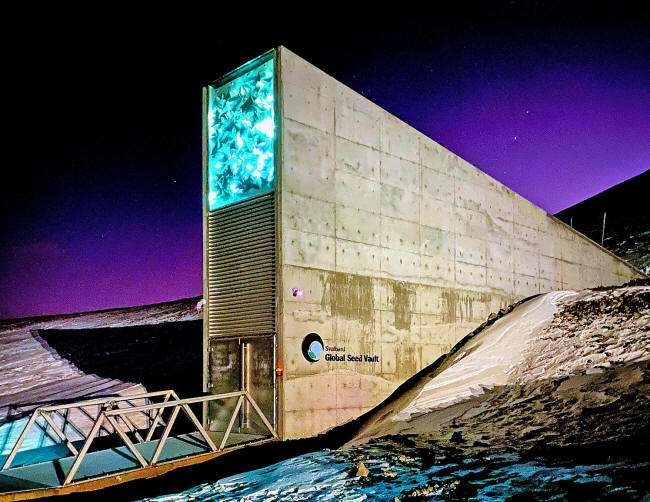

Image of the entrance to the Svalbard Global Seed

in Svalbard, Norway, a remote archipelago in the Arctic Ocean.

Photo by Subiet via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

-

The global network of plant gene banks has shown

resilience and cooperation, growing in importance as

an estimated 40% of plant species are threatened

with extinction and the crops used to feed the world

become less diverse.

-

A newly published paper documents the rescue mission

of seeds from a gene bank in Syria to the Svalbard

Global Seed Vault in Norway, and discusses the

extensive global system for conserving crop

diversity and why it is imperative to do so.

-

While Svalbard's vaults store crop seeds, the

Millennium Seed Bank at the Royal Botanic Gardens,

Kew, is the world's largest wild seed conservation

project, now celebrating its 20th anniversary.

-

Gene banks are an important part of conservation,

but they are not sufficient on their own, one expert

says; the wild places and agro-ecosystems these

plants come from must also be protected.

By the time the

war broke out in Syria, researchers

from the International Center for Agricultural Research in the

Dry Areas (ICARDA)

had already duplicated and safely transported most of their genetic

treasure trove to the

Svalbard Global Seed Vault

(investments by

Bill Gates,

Rockefeller and GMO Giants) on the remote

Arctic island of Spitsbergen, Norway.

The ICARDA facility in Tel Hadia, just south of Aleppo, Syria, once

stored the largest collection of crop diversity from the Fertile

Crescent, one of the world's earliest centers of agriculture.

When the facility was

abandoned in 2014, more than 80% of its collection was backed up in

the Norwegian vault.

"When the Arab Spring

started, Syria was still considered a very secure and stable

country, and then it became complete chaos, as we know," Ola

Westengen, an associate professor at the Norwegian

University of Life Science who was coordinator of operations

and management at the Svalbard Global Seed Bank at the time of

the seed rescue, told Mongabay.

"[B]ut one should not

give the impression that the seeds were somehow smuggled out or

sent out in a clandestine way, everything was by the book."

The safe and peaceful

transfer of the samples from Syria, despite extreme conditions,

Westengen says, is a testament to how well the international system

of gene banks is working.

Westengen is the co-author of a newly published paper (Safeguarding

a Global Seed Heritage from Syria to Svalbard) in the

journal Nature Plants that documents the seed rescue mission and

lessons learned from the operation, which, the paper says,

illustrates the links between food security, sociopolitical

stability, and climate change.

The paper also discusses

the extensive global system for conserving crop diversity and why it

is imperative to do so.

Diversity in farmers' fields is decreasing, with an

estimated 90% of humanity's caloric

intake reliant on just rice, maize and wheat.

Threats to crop diversity

are addressed in international conservation goals such as,

-

the U.N.'s

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

-

the International

Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Plant

Treaty)

-

the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs)

A network of

international centers preserves regional plant diversity and makes

these seeds available to researchers and plant breeders under the

conditions of the Plant Treaty, not only to respond to

regional disasters but also to develop new varieties that are

resilient in the face of challenges such as drought and disease.

mmm mmm

The seed of a wild relative of the carrot, Daucus carota.

This plant is not edible,

but

it may have genetic traits that could be of use.

Because it can withstand harsher growing conditions

than the supermarket carrot,

its genes may be used to create carrot varieties

that can withstand pressures from climate change.

Photo by Rob Kesseler.

Ideally, important digital information is backed up to "the cloud"

or a hard drive.

Likewise, the

important crop genetics from regional seed banks are backed up

in the

Svalbard Global Seed Vault...

The vault, built inside a

mountain on the remote Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, opened in

2008 with the intention of being a politically neutral and safe

location to protect the world's crop diversity.

Samples sent here are

duplicates from seed and gene banks, research facilities, and

communities around the world, ranging from large institutions like

ICARDA, to the Cherokee Nation, who, this year, became the first

tribe in the U.S. to send important heirloom seeds to Svalbard.

But unlike files on a hard drive, seeds in a vault cannot be

stored and forgotten...!

Even in the ideal,

supercooled (-18°C, -0.4°F) conditions of the Svalbard vault,

seeds have a shelf life...

It is up to each

institution providing seeds to be sure the collections in the vaults

are regularly updated with fresh, viable samples.

"In some of the

stories about the seed vault, you get the impression that this

is like a time capsule," Westengen said.

"But the seed vault

only makes sense as part of a kind of dynamic system for

conserving and keeping the seeds viable... all seeds need

to be regenerated and grown out in an environment where

they will maintain their genetic integrity.

And that's a much

more demanding job."

In 2015, the ICARDA

facilities in Lebanon and Morocco began undertaking the mammoth task

of regenerating in the field the plants rescued from Syria, an

operation requiring complex logistics and large areas to regrow

thousands of different species.

But they have been

successful...

All of the safety

duplicates stored in Svalbard were regenerated by September of this

year (2020).

"It has been a

massive effort," Mariana Yazbek, co-author of the paper

and gene bank manager at the ICARDA facility in Lebanon, told

Mongabay.

"[O]ur team

sacrificed nights and weekends sometimes to ensure this limited

resource of seeds was regenerated... We are reaping the benefits

of this work now, quite literally."

ICARDA Lebanon Genebank Manager Mariana Yazbek (left),

says workers have continued to come to work on a rotating schedule

to keep plants alive throughout the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Image courtesy of ICARDA.

This year, gene banks have faced the added challenge of keeping

critical plants alive during the

COVID-19 'pandemic'.

While some seeds can be

left on the shelves for months or even years, conserving roots,

tubers and other crops that are not grown from seed such as,

potatoes, cassava

(yuca),

yams and some bananas,

...require more

attention.

These plants cannot be

stored for long, and are not backed up at Svalbard, so they must be

grown nearly continuously.

When the lockdowns began

in Lebanon, for instance, ICARDA staff worked on a rotating

schedule, traveling only between their homes and work to keep the

plants alive.

At another facility, the International Center for Tropical

Agriculture (CIAT)

in Colombia, researchers preserve many important tropical-adapted

crops such as cassava.

CIAT has many different

genotypes of cassava, all cultivated without seeds, requiring daily

work.

This year, its staff of

900 was moved to a rotating schedule, with about 300 people coming

in each day to keep plants alive and critical experiments running.

"Perhaps you think

that the middle of a global 'pandemic' is not an appropriate

time to be discussing seed banks. Think again,"

...Luigi Guarino, director of science, and

Charlotte Lusty,

head of programs and gene bank platform coordinator at

Crop Trust, an organization

that supports the Svalbard Global Seed Vault as well as

genebanks around the world, wrote in

Landscape News.

"One thing is

certain, to mitigate the effects of future shocks of the kind

we're currently experiencing, and to allow us to bounce back

from them, there needs to be diversity in all parts of the food

chain."

Cassava, also called yuca,

is an

important global food crop

that

cannot be stored using seeds.

Photo

by David Monniaux via Wikimedia Commons

(CC

BY-SA 3.0).

Guarino and Lusty say that maintaining crop diversity is an

essential task, even during a 'pandemic', to future-proof the

world's crops from impacts related to climate change, natural

disasters, or conflict.

"There is kind of a

global system that, unfortunately, very few people appreciate

until there is a tragedy," Joseph Tohme, agrobiodiversity

research area director at CIAT, told Mongabay.

"Every center can

provide you kind of stories...

In our case, we had a

major project called Seeds of Hope for Rwanda, because

during and after the genocide, Rwanda lost a major collection of

beans."

One tragedy, the

human-caused annihilation of global plant and animal species, known

as the sixth mass extinction, is currently underway.

An estimated 40% of

plant species are

threatened with extinction,

according to a report released by the Royal Botanic Gardens,

Kew.

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew's

Millennium Seed Bank is working

to save some of that diversity.

While the Svalbard

vault store crop seeds, the Millenium Seed Bank, located

in Wakehurst, U.K, safeguards seeds of the planet's imperiled wild

plants.

The Millenium Seed Bank, the world's largest wild seed

conservation project, celebrated its 20th anniversary

this year.

Its vault, built to

withstand bombs, radiation and floods, holds 2.4 billion seeds from

39,681 species, coming from 190 countries and territories.

The facility and its

partners say they have helped to protect 16% of the world's

seed-bearing plants.

Seeds of the world's wild plants

in cold

storage at the Kew Millennium Seed Bank,

Photo

courtesy of Royal Botanical Gardens Kew.

Among its collection are eight species now extinct in the wild.

One of these, the last

known wild yellow fatu flower (Abutilon pitcairnense), was

taken out by a landslide on Pitcairn Island in the Southern Central

Pacific, the only place where it was found.

The seeds were already

saved at Millennium Seed Bank, and are now cultivated in its

greenhouses.

"If that material

hadn't already been collected, then when that landslide wiped

out the one remaining plant, we would have had nothing.

We would have had no

trace of that species, which is now extinct in the wild,"

Elinor Breman, senior research leader in seed conservation

at the Millennium Seed Bank, told Mongabay.

The wild yellow fatu flower (Abutilon pitcairnense)

is

now considered extinct in the wild,

but lives on at the Kew Royal Botanical Gardens.

Photo by Marcella Corcoran.

Like the Svalbard vault, the Millennium Seed Bank has

responded in the wake of catastrophe.

The massive bushfires in

Australia earlier this year burned 23,200 hectares (57,300 acres) in

Cudlee Creek near Adelaide.

The Millennium

Seed Bank sent backup seeds of clover glycine (Glycine

latrobeana), a rare, wild pea, to its partners in Australia so

that the plant could be cultivated and used to restore the

ecosystem.

Research on the science of seed and gene banking is ongoing at

the Millennium Seed Bank, including the development of

cryopreservation methods to store roots and tubers.

Along with their

international partners, they are researching useful plant traits and

testing species' responses to environmental stressors such as

drought and higher temperatures, predicted to increase as the

climate changes.

The Millennium Seed Bank also safeguards some of the wild

relatives of crops, the plants from which many of our foods were

cultivated.

Conserving crop diversity

involves protecting the entire gene pool of a crop and that includes

its wild ancestors.

Researchers in the -20°C Kew Millennium Seed Bank vault.

The sign reads, "Yunan banana (Musa itinerans)…

marked 10% of the world's plant species being banked here."

Photo courtesy of Royal Botanical Gardens Kew.

Gene banks are an important part of conservation, says Westengen,

but they are not sufficient on their own.

A continuum exists

between ex-situ (off-site) and in in-situ (in-place) conservation,

so the wild places and agro-ecosystems these plants come from must

also be protected.

"This is something

that we all depend on. This is a common heritage. It's not

something that especially benefits any one side in a conflict,"

Westengen said.

"The issue of seeds

is actually quite politicized globally... but

pretty much everyone agrees that we need to conserve this

diversity."

Citation

-

Westengen, O. T.,

Lusty, C., Yazbek, M., Amri, A., & Asdal, Å. (2020).

Safeguarding a global seed heritage

from Syria to Svalbard. Nature Plants, 6(11),

1311-1317. doi:10.1038/s41477-020-00802-z

|