|

by Michael Tsarion

September

2022

from

MichaelTsarion Website

To find

out

what is truly

individual in ourselves,

profound

reflection is needed;

and suddenly we

realize how

uncommonly difficult

the

discovery of individuality is.

Carl Jung

It is not possible for you to know what it's like to be anyone but

yourself.

You will never know what it is like to be someone else. You can

ponder what it is like but you're already off to a bad start,

because the word "like" doesn't really mean what it appears to mean.

The word suggest metaphor. What's that about, one asks?

If all I am capable of knowing is what something or someone is

"like," then obviously I do not have direct access to what it truly

is in itself. It's actual identity remains strangely concealed.

Why is this the case?

If I'm astute, I must ask this question, and find out whether

there's a good reason for things to be this way. Maybe if I was able

to know what it's like to be someone else, completely and

distinctly, I'd lose the person I take myself to be.

Perhaps I'm here not to know what it's like to be other people, but

to be myself. Isn't there enough mystery in this?

I can certainly see what I have in common with this or that person,

but I'm not so clear on what makes my identity unique. Many people

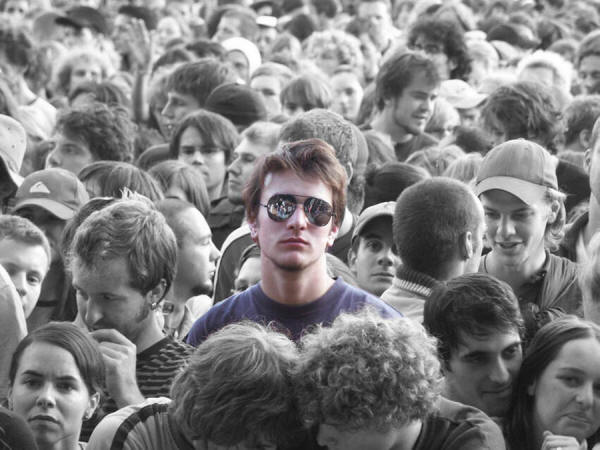

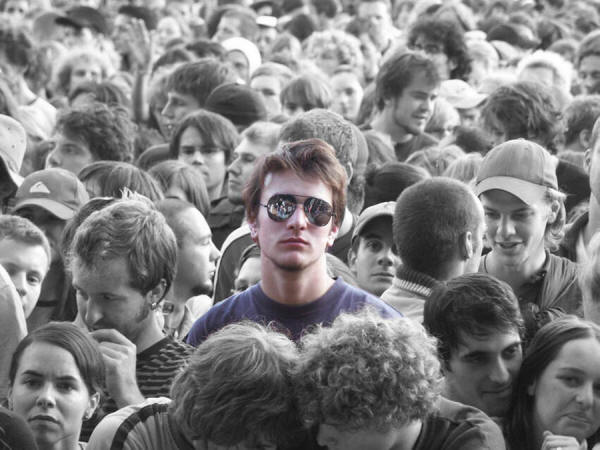

go through life never inquiring into this difference. Most people

are afraid of being different from others in the world. It's a cause

of anxiety.

A few people realize the preciousness of individuality, and do their

best to augment what it is that separates them from the Crowd. If

this attitude is pursued to its extreme, one becomes something of an

Outsider, which can lead to feelings of alienation.

This in turn breeds its

own kind of anxiety.

Sigmund Freud noted that there are basically two forms of

anxiety, legitimate and neurotic.

Paraphrasing Freud, we

can say that there is legitimate suffering and neurotic misery. The

latter is experienced when we are unable to get approval from other

people. We are flooded with guilt over not fitting in and behaving

like them.

One suffers from a

Guilt-Complex...

Alternatively, we can also feel shame for conforming and doing as

others do. Shame is not the same as guilt. Simply stated, guilt

relates to our infractions against others, whereas shame is

generated from within in response to violations committed against

the Self.

From this we see that humans are morally divided beings.

There are two opposing

centers of morality - the superego and the

conscience, and we endure a daily tug-of-war between them -

between our duties to the world, to others, and our sovereign duty

toward ourselves as Selves.

There's bound to be conflict and pain either way. This is the

extraordinary predicament facing humanity. It was the reason for the

advent of psychoanalysis.

One should be able to

seek help when they feel flooded with shame or guilt.

Animals cannot strive to change their behavior.

Only human beings have the will and wherewithal to

upgrade themselves.

Only humans can Individuate, and know it.

We change due to the pressures of the world, and

because there's something natural within us that

strives for greater understanding and awareness.

This organic process behind psychic progress is

known as entelechy or teleology.

It fascinated Jung as it had Aristotle centuries

earlier.

Since it is a phenomenon not ordained by the will,

suggests that the so-called "unconscious" is not to

be dismissed as unimportant and inconsequential.

A simple solution to the

problem of guilt is to not do as one likes.

Doing as others do helps

me fit in, and by fitting in I experience less anxiety. It feels

good to belong and get the approval of parents, friends and

associates.

Life is a lot easier to

handle.

I don't stand out,

and don't annoy others by honestly confessing how I see things.

They don't want to

know anyway, and I just make a fool of myself trying to be

"different."

I don't want to rock

the boat and have people avoid me.

Sadly, this conformist

approach doesn't work. I'm not at peace, because something within

bugs me.

It's that pesky

existential shame. Every time I act in a way that violates my true

inner voice, I am beset with shame. There's no way to alleviate it

until I make the firm decision to be myself and speak honestly about

my feelings and ideas.

Doing so lessens feelings

of shame, but ups my feelings of guilt.

What a terrible

predicament to be in.

This is the reason so

many people today decide to take medication.

The stress proves too

much and one can no longer cope.

Fast and furious lifestyles and fast and furious

cures for all ills.

Psychoanalysis was founded to help people who get

flooded with guilt or shame.

Sky-rocketing rates of medication dependency shows

that people just want easy, convenient panaceas for

all problems.

They do not want to develop emotional intelligence

or move beyond a recreational, episodic existence.

But who or what is this "Self" sitting at the center of it all?

That question has plagued science for centuries, and is known as the

"Hard Problem."

Everything material that makes up a human being - the skin, muscle,

bone, nerves and little grey cells, etc - cannot be said to be

"conscious". They function but do not "experience" anything. Even

the brain, with its grey matter, lobes and neurons, isn't the seat

of any tangible biographical Self.

Whatever Selfhood is, it

does not seem to have an actual address in time and space.

Recently, however, advances in science have been made.

Neuroscientists such as Mark Sohms and others now recognize that

what constitutes a Self, isn't intellect but feeling.

In English we don't have too many words for feeling. Nevertheless,

emotion or feeling is now acknowledged as the center of one's being.

What we know as subjectivity is entirely based upon it.

When we introspect, we willingly turn within, as it were, to assess

how we feel about a certain person or situation. We do this

constantly. We do it so much that we forget doing it. It's so

natural and effortless. However, according to Sohms, there's another

dimension to take into consideration when it comes to feeling.

There's another kind of feeling action taking place all the time,

that is natural but not willed. It's what the body itself does to

bring us the experiences making us who we are.

This is known as

introception...

What we know as intellect, thought and reason are, in fact, now

understood as epiphenomena of introception or feeling. It's known

that the brainstem conveys feelings from the nervous system and body

- up to 80 percent of the information processed by the brain comes

from the soma.

As said, the process of introspection holds the key to the Hard

Problem puzzle. When we go within our minds, it isn't to think about

things. It's more a case of checking how we feel about them.

We feel how we feel, and

do so continually, hundreds of times a day. The object of this

interminable self-reflexivity is biopsychic homeostasis.

Once achieved we

experience pleasure. When not achieved we suffer pain...

This fundamental process gave rise to emotion and also to intellect.

It also gave rise to language. As said above, metaphors are a matter

of spoken language.

When I ask myself what it

is "like" to be me, I am really speaking in metaphors.

I'm not actually

speaking of me at all, but what it's "like" to be me. Due to the

paradoxes of language I'm always talking about something other

than what I intend talking about.

This begs the question,

do I actually experience being me, or do I experience being

something "like" me?

Perhaps there's no answer to this question. Scholars such as

Julian Jaynes and Erich Fromm, etc, insisted that the

"me" is a very recent phenomenon.

Identity as we know it is

a late historical experience. Humans thought very differently in

ancient times. Their concepts of "me" and "you" were not the same as

ours.

Many a Copernican

Revolution in consciousness has taken place since the days of old.

There was

a time

when

rational present-day consciousness

was not yet

separated

from the

historical psyche,

the collective

unconscious

Carl Jung

Where is the dividing line between you and me?

Despite the oddities of language and metaphor, most moderns have a

continuous biographical sense of being.

We intuit a past,

present and future, and have personal needs and desires. Our

bodies feel real and our memories are certainly ours.

We have no difficulty

distinguishing ourselves from others.

It might be said that the senses are also an extension of

feeling. It's not normal for us to think of perception as a kind

of feeling. This is, however, consistent with the ideas of

French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

We don't just see a world of objects, we feel them.

According to philosopher

Martin Heidegger, our whole mental and physical make-up is

determined by our Being-in-the-World.

This state of being

presumes a deep symbiosis between self and world. This was axiomatic

to both Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty. Moods are, for example, proof

of this nonconscious interconnectivity.

For these men there is no

such thing as a "Hard Problem", nor is there any validity to the

subject versus object dichotomy, at least not in any hard Cartesian

sense.

French

philosopher

Maurice

Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961),

explored the

deep connections between Self and World.

His exceptional

work on man as perceiver

utterly

undermines Cartesian notions

of a hard divide

between subjects and objects,

Self and World.

Modern science

still has to honor

his far-reaching

findings.

As Schelling said, hundreds of years ago, the so-called "object" is

taken inside the mind, and thereby loses its objectivity.

Likewise, the subject is

so immersed in the world, that he too ceases to be a pure subject in

any definitive sense. Being human, then, is to already be a being

that nucleates opposites.

In other words, as the Existentialists see it, my subjectivity is

composed of world, and what I call world is composed of Self. Better

said, both World and Self are two expressions of a single reality, a

single experience. There is certainly no hard distinction between

them.

Thus, a basic tenet of

materialistic science is rendered null and void.

But again, as science now recognizes, what we call the subject is

based on feeling. Therefore, what we call senses must be understood

as emanations of this basal feeling state. By way of the senses we

feel our world.

We are selves within our

environments and without our place of dwelling there can be no sense

of Self.

Realizing this is vital, say the Existentialists, because it is from

this "place" of being that we reach out to other people. They too

occupy a world. It's what everyone has in common. What makes people

different is how they occupy their place of being.

How does one "dwell"

where they are?

It determines not

only how one relates to the rest of humankind, but to oneself as

a Self.

The so-called "subject"

is, therefore, not to be defined in the Cartesian way.

The subject is not what

it is because of its distinction from a world of external objects.

What we call objects are not set apart from the subject in the way

traditionally conceived.

This is because every

object encountered outside us has an enormous bearing on what we

know ourselves as, or what we feel ourselves to be.

Objects in the world stand as all-important coordinates by which we

judge our feelings about self and world. They are the means by which

Selfhood is oriented. As Schelling held, the objective world is the

means by which we become subjects.

Similarly, the objective

world is intimately articulated to the subject-hood emerging from

it. This means that there is something mental about matter and

something material about mind.

Mind and matter are

therefore to be understood as two expressions or polarities of a

single principle, that of Spirit.

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775-1854) is the

world's foremost forgotten philosopher.

His

profound ideas have been appropriated by dozens of later

thinkers, often without citation.

"…withdrawing into ourselves, the perceiving self

merges in the self-perceived.

At that moment we annihilatetime and duration of

time; we are no longer in time, but time, or rather

eternity itself, is in us.

The external world is no longer an object for us,

but is lost in us."

Friedrich

Schelling

Now that science has

finally established the constitution of the Self or subject, the

Hard Problem is no longer a problem.

The question remains, what does it mean for an individual to

experience his or her Selfhood, now that it is something substantial

enough to be experienced?

Well done science...!

After hundreds of years

the penny has dropped. Thanks for finally confirming that what I

experience isn't just a gas, the vapor of complex mechanical

biological and nervous systems.

What I know about "myself" is primarily a matter of feeling.

Moreover, the world I find myself occupying is also felt. It is not

something standing outside or beyond me.

Rather it is encompassed

by me.

What I call "I" is in

the world as world is inside me.

It is no longer a

thing coldly and impersonally observed from a distance.

Of course we know that

science has never asked "how does one feel about the world?" It asks

only what I "know" about it. That's the new Hard Problem.

Thankfully, progress is being made.

Mark Sohms,

David Bohm, Iain McGilchrist Michael Gazzaniga, Bruce

Lipton,

Rupert Sheldrake, and many other top level

scientists have sickened of scientism and are far more open to

alternative viewpoints and theories about the nature of reality.

They are keen to embrace

the ideas of Existentialist thinkers and to reconsider the veracity

of Cartesianism.

Hundreds of years ago David Hume refuted the foundations of

materialistic science, showing that causality is merely a matter of

assumption and contingency.

His challenge has never

been met. John Locke's doctrine on the fundamental principles of

science have long been overturned.

Likewise his assessment

of the nature of consciousness is also null and void. In other

words, materialism is dead, and the top brass know it. It has been

panic stations for some time now.

Hard-line materialists turn to the lineaments of language in a last

ditch effort to hold the fort and salvage what's left of their

bankrupt paradigms.

George Lakoff, for

example, explores the phenomenon of metaphor, to prove that we are

nothing more than creatures of Darwinian evolution.

In Lakoff's estimation we are simply creatures attempting to orient

ourselves in a hostile world. We are subjects relating to wholly

independent antithetical objects. In so doing we developed language.

Our brains split and we

developed communication skills via the Left-Hemisphere.

Ironically, his

description of the function of the Left-Brain in this regard

contradicts his cherished theories on the nature of consciousness

and role of language.

This is because the Left-Brain's foremost job is to reduce and focus

on the world before us. This means leaving out a great deal of

content, both inwardly and outwardly.

It follows that we do not

refer to something so necessarily narrow and limited to learn

anything substantial about reality and consciousness, not unless

we're involved in intellectual chicanery.

Lakoff does not address how our disorientation arose and why

language is so "colorful."

Why all the

metaphors?

Why the displacement

suggested in every metaphor?

Why all the "likes?"

When

we speak, we also listen.

The

inner monologue is actually more of a dialogue between

two inner selves - speaker and listener.

Our

language is excessively expressive and colorful. Is this

due to Darwinian evolution, as neo-materialists profess?

Why

do we write poetry and love obscure jokes? When violent

criminals develop better communication skills, they

often cease committing crimes.

Why

is this?

We've noted the peculiar fact that to be "like" something is to not

be what one is.

Why on earth develop

such a language?

Why call it

"communication?"

Why say that nothing

is what it is, it's always "like" something else?

When we turn to that

something else, it too turns out to be "like" something else.

What on earth is

going on?

Is anything or anyone

known for what it is?

Materialism says no!

It seems that we're back to Kant's impermeable wall between the

known and unknown. Of course, the contradiction looms large.

If there's nothing to

know at all, where did the "knower" come from?

If life is only about

survival and survival skills, why develop such an overwhelming

drive to "know" about things if, as Lakoff holds, there's

nothing to know?

Well, this is what one

gets when towers are burning.

We get ideas that attempt

to undermine the purpose for which humans exist. We get preposterous

unfalsifiable notions such as,

...from men of science breaching their own supposedly

sacrosanct rules.

Science has long been

about dogma and smoke and mirror play.

It has long avoided the

important questions, and has never acknowledged the supreme role of

feeling. Indeed it has established itself by utterly negating it.

Centuries have been wasted. Science now finds itself confronted with

the questions it previously rejected.

What is it to be a

Self?

How does one express

what it is to be a Self?

Why create a language

that makes the problem even worse, that leads us away from where

we want to go?

Fortunately, we can now officially ask - if a thing cannot be

known in itself, can it be felt for what it is?

What does the "knower" know and feel about themselves? How does

one come upon their understanding?

How does the psyche

divide itself into subject and object, knower and known?

How did our inner

dialogue (or autologue) come about?

Is the voice we hear

inside our heads really our own?

Interesting questions to

be sure - best not ask a Cartesian or Materialist for the answers.

Man has

developed consciousness

slowly and laboriously,

in a process

that took untold ages

to reach the civilized state…

And this

evolution is far from complete,

for large areas

of the human mind

are still shrouded in darkness.

What we call the

"psyche"

is by no means identical

with our

consciousness and its contents.

Carl Jung

Now that it has been established that feeling is the essence if not

the cause of consciousness, a lot of obscure matters are clarified.

It is, for example, axiomatic that feelings cannot be shared.

Certainly, one cannot know what it is like to be another person, and

just as certainly we cannot feel like someone else. This is where

science gets off.

If feeling is the bottom

line, as Personalists hold, then they are hermetically sealed, so to

speak. It is the individual who feels - who introspects and

introcepts.

He does so within

himself, and for all the color of language he cannot really express

his feelings to others. Moreover, the other is caught up

experiencing their own feelings, every minute of the day and night.

What we share are words and language, not feelings.

Schelling stressed the uniqueness of human beings. He described the

age-old teleological movement from unconsciousness to consciousness

to self-consciousness.

Only humans are lucidly self-conscious beings.

Indeed, to invent science and ask scientific questions about

consciousness and reality presupposes self-consciousness. Therefore,

implies Schelling, it follows that self-consciousness is the

greatest mystery of all. Odd that it isn't even considered by most

people.

This truly holy mystery

isn't important to people as they go about thinking, feeling and

acting.

But as said, this is where science gets off. Whatever answers there

are to this mystery - the

mystery of the Self - they will not

be discovered and broadcast collectively.

There is no end to the mystery of the Self.

Schelling, Hegel,

Blake, Barfield, Buber, Jung and others of their kind knew it.

The Self is not a

butterfly to be caught, killed and pinned to a board.

Jung would say that whatever one intuits about the nature of the

psyche is afforded by the psyche.

As he rightly declared,

the psyche is not in us.

Rather, we are in the

psyche...

|