WIRED: How did you come to

believe in

panpsychism?

Christof Koch: I grew up Roman Catholic, and also grew up with a

dog. And what bothered me was the idea that, while humans had

souls and could go to heaven, dogs were not suppose to have

souls.

Intuitively I felt that either humans and animals alike

had souls, or none did. Then I encountered Buddhism, with its

emphasis on the universal nature of the conscious mind.

You find

this idea in philosophy, too, espoused by Plato and Spinoza and

Schopenhauer, that

psyche - consciousness - is everywhere.

I

find that to be the most satisfying explanation for the

universe, for three reasons:

-

biological

-

metaphysical

-

computational

'What is the simplest explanation? That consciousness extends to

all these creatures...'

WIRED: What do you mean?

Koch: My consciousness is an undeniable fact.

One can only infer

facts about the universe, such as physics, indirectly, but the

one thing I'm utterly certain of is that I'm conscious. I might

be confused about the state of my consciousness, but I'm not

confused about having it.

Then, looking at the biology, all

animals have complex physiology, not just humans. And at the

level of a grain of brain matter, there's nothing exceptional

about human brains.

Only experts can tell, under a microscope, whether a chunk of

brain matter is mouse or monkey or human - and animals have very

complicated behaviors. Even honeybees recognize individual

faces, communicate the quality and location of food sources via

waggle dances, and navigate complex mazes with the aid of cues

stored in their short-term memory.

If you blow a scent into

their hive, they return to where they've previously encountered

the odor. That's associative memory. What is the simplest

explanation for it?

That consciousness extends to all these

creatures, that it's an immanent property of highly organized

pieces of matter, such as brains.

WIRED: That's pretty fuzzy. How does consciousness arise? How

can you quantify it?

Koch: There's a theory, called

Integrated Information Theory,

developed by Giulio Tononi at the University of Wisconsin, that

assigns to any one brain, or any complex system, a number - denoted by the Greek symbol of Φ

- that tells you how integrated

a system is, how much more the system is than the union of its

parts.

Φ gives you an information-theoretical measure of

consciousness.

Any system with integrated information different

from zero has consciousness. Any integration feels like something.

WIRED: Ecosystems are interconnected. Can a forest be

conscious?

Koch: In the case of the brain, it's the whole system that's

conscious, not the individual nerve cells.

For any one

ecosystem, it's a question of how richly the individual

components, such as the trees in a forest, are integrated within

themselves as compared to causal interactions between trees.

The philosopher John Searle, in his review of Consciousness,

asked,

"Why isn't America conscious?"

After all, there are 300

million Americans, interacting in very complicated ways.

Why

doesn't consciousness extend to all of America? It's because

integrated information theory postulates that consciousness is a

local maximum.

You and me, for example: We're interacting right

now, but vastly less than the cells in my brain interact with

each other. While you and I are conscious as individuals,

there's no conscious ▄bermind that unites us in a single entity.

You and I are not collectively conscious.

It's the same thing

with ecosystems. In each case, it's a question of the degree and

extent of causal interactions among all components making up the

system.

WIRED: The Internet is integrated. Could it be conscious?

Koch: It's difficult to say right now. But consider this.

The Internet contains about 10 billion computers, with each computer

itself having a couple of billion transistors in its CPU.

So the

Internet has at least 1019 transistors, compared to the roughly

1000 trillion (or quadrillion) synapses in the human brain.

That's about 10,000 times more transistors than synapses.

But is

the Internet more complex than the human brain? It depends on

the degree of integration of the Internet.

For instance, our brains are connected all the time.

On the

Internet, computers are packet-switching. They're not connected

permanently, but rapidly switch from one to another. But

according to my version of panpsychism, it feels like something

to be the Internet - and if the Internet were down, it wouldn't

feel like anything anymore.

And that is, in principle, not

different from the way I feel when I'm in a deep, dreamless

sleep.

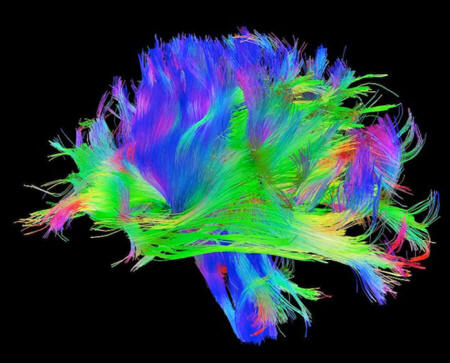

A map of the

Internet, circa 2005.

Image: The Opte Project

WIRED: Internet aside, what does a human consciousness share

with

animal consciousness? Are certain features going to be the

same?

Koch: It depends on the sensorium [the scope of our sensory

perception - ed.] and the interconnections.

For a mouse, this is

easy to say. They have a cortex similar to ours, but not a

well-developed prefrontal cortex. So it probably doesn't have

self-consciousness, or understand symbols like we do, but it

sees and hears things similarly.

In every case, you have to look at the underlying neural

mechanisms that give rise to the sensory apparatus, and to how

they're implemented. There's no universal answer.

WIRED: Does a lack of self-consciousness mean an animal has no

sense of itself?

Koch: Many mammals don't pass the mirror self-recognition test,

including dogs.

But I suspect dogs have an olfactory form of

self-recognition. You notice that dogs smell other dog's poop a

lot, but they don't smell their own so much. So they probably

have some sense of their own smell, a primitive form of

self-consciousness.

Now, I have no evidence to suggest that a

dog sits there and reflects upon itself; I don't think dogs have

that level of complexity. But I think dogs can see, and smell,

and hear sounds, and be happy and excited, just like children

and some adults.

Self-consciousness is something that humans have excessively,

and that other animals have much less of, though apes have it to

some extent. We have a hugely developed prefrontal cortex. We

can ponder.

WIRED: How can a creature be happy without self-consciousness?

Koch:: When I'm climbing a mountain or a wall, my inner voice is

totally silent.

Instead, I'm hyperaware of the world around me.

I don't worry too much about a fight with my wife, or about a

tax return. I can't afford to get lost in my inner self. I'll

fall. Same thing if I'm traveling at high speed on a bike.

It's

not like I have no sense of self in that situation, but it's

certainly reduced. And I can be very happy.

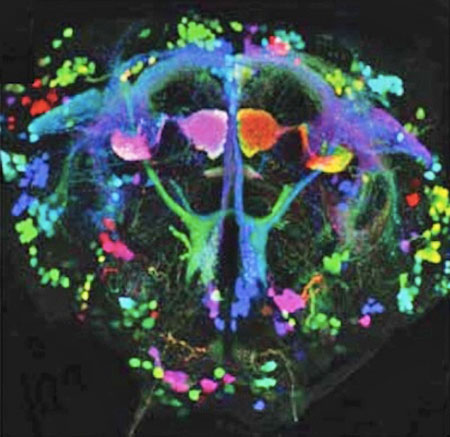

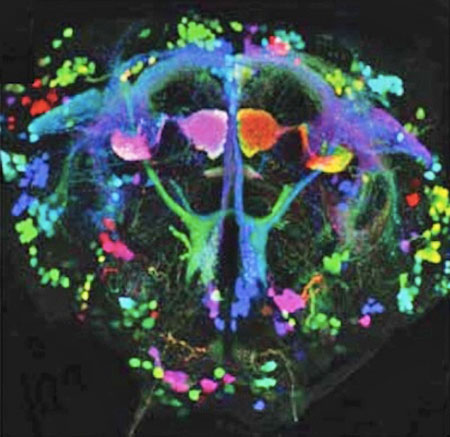

Neural pathways in the brain of a fruit fly.

Image: Hampel et

al./Nature Methods

WIRED: I've read that you don't kill insects if you can avoid

it.

Koch: That's true. They're fellow travelers on the road,

bookended by eternity on both sides.

WIRED: How do you square what you believe about animal

consciousness with how they're used in experiments?

Koch: There are two things to put in perspective.

First, there

are vastly more animals being eaten at McDonald's every day. The

number of animals used in research pales in comparison to the

number used for flesh. And we need basic brain research to

understand the brain's mechanisms.

My father died from

Parkinson's. One of my daughters died from Sudden Infant Death

Syndrome.

To prevent these brain diseases, we need to

understand

the brain - and that, I think, can be the only true

justification for animal research. That in the long run, it

leads to a reduction in suffering for all of us.

But in the

short term, you have to do it in a way that minimizes their pain

and discomfort, with an awareness that these animals are

conscious creatures.

WIRED: Getting back to the theory, is your version of

panpsychism truly scientific rather than metaphysical? How can

it be tested?

Koch: In principle, in all sorts of ways.

One implication is

that you can build two systems, each with the same input and

output - but one, because of its internal structure, has

integrated information. One system would be conscious, and the

other not. It's not the input-output behavior that makes a

system conscious, but rather the internal wiring.

The theory also says you can have simple systems that are

conscious, and complex systems that are not.

The cerebellum

should not give rise to consciousness because of the simplicity

of its connections. Theoretically you could compute that, and

see if that's the case, though we can't do that right now. There

are millions of details we still don't know. Human brain imaging

is too crude. It doesn't get you to the cellular level.

The more relevant question, to me as a scientist, is how can I

disprove the theory today. That's more difficult.

Tononi's group

has built a device to perturb the brain and assess the extent to

which severely brain-injured patients - think of

Terri Schiavo - are truly unconscious, or whether they do feel pain and distress

but are unable to communicate to their loved ones.

And it may be

possible that some other theories of consciousness would fit

these facts.

WIRED: I still can't shake the feeling that consciousness

arising through integrated information is... arbitrary, somehow.

Like an assertion of faith.

Koch: If you think about any explanation of anything, how far

back does it go? We're confronted with this in physics.

Take

quantum mechanics, which is the theory that provides the best

description we have of the universe at microscopic scales.

Quantum mechanics allows us to design

MRI and other useful

machines and instruments.

But why should quantum mechanics hold

in our universe? It seems arbitrary!

Can we imagine a universe

without it, a universe where Planck's constant has a different

value? Ultimately, there's a point beyond which there's no

further regress. We live in a universe where, for reasons we

don't understand, quantum physics simply is the reigning

explanation.

With consciousness, it's ultimately going to be like that. We

live in a universe where organized bits of matter give rise to

consciousness.

And with that, we can ultimately derive all sorts

of interesting things:

the answer to when a fetus or a baby

first becomes conscious, whether a brain-injured patient is

conscious, pathologies of consciousness such as schizophrenia,

or consciousness in animals.

And most people will say, that's a

good explanation.

If I can predict the universe, and predict things I see around

me, and manipulate them with my explanation, that's what it

means to explain. Same thing with consciousness.

Why we should

live in such a universe is a good question, but I don't see how

that can be answered now.