|

Contents

-

English Version

-

Version en Español

Tikal

from

Wikipedia Website

Tikal (or Tik’al according to the modern

Mayan orthography) is one of the largest archaeological sites and

urban centers of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization.

Tikal Temple I rises

47 meters (150 ft) high.[1]

It is located

in the archaeological region of the Petén Basin in what is now

modern-day northern Guatemala. Situated in the department of El

Petén, the site is

part of Guatemala's Tikal National Park and in

1979 it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[2]

Tikal was the capital of a conquest state that became one of the

most powerful kingdoms of the ancient Maya.[3] Though

monumental architecture at the site dates back as far as the 4th

century BC, Tikal reached its apogee during the Classic Period, ca.

200 to 900 AD.

During this time, the city dominated much of the Maya

region politically, economically, and militarily, while interacting

with areas throughout Mesoamerica such as the great metropolis of

Teotihuacan in the distant Valley of Mexico.

There is evidence that Tikal was

conquered by Teotihuacan in the 4th century AD.[4]

Following the end of the Late Classic Period, no new major monuments

were built at Tikal and there is evidence that elite palaces were

burned. These events were coupled with a gradual population decline,

culminating with the site’s abandonment by the end of the 10th

century.

Tikal is the best understood of any of the large lowland Maya

cities, with a long dynastic ruler list, the discovery of the tombs

of many of the rulers on this list and the investigation of their

monuments, temples and palaces.[5]

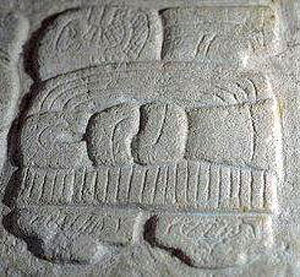

Emblem Glyph for Tikal (Mutal)

Etymology

The name Tikal may be derived from ti

ak'al in the Yucatec Maya language; it is said to be a relatively

modern name meaning "at the waterhole". The name was apparently

applied to one of the site's ancient reservoirs by hunters and

travelers in the region.[6]

It has alternatively been interpreted as

meaning "the place of the voices" in the Itza Maya language. At any

rate, Tikal is not the ancient name for the site but rather the name

adopted shortly after its discovery in the 1840s.[7]

Hieroglyphic inscriptions at the ruins refer to the ancient city as

Yax Mutal or Yax Mutul, meaning "First Mutal".[6]

Tikal may have come to have been called

this because Dos Pilas also came to use the same emblem glyph; the

rulers of the city presumably wanted to distinguish themselves as

the first city to bear the name.[8]

The kingdom as a whole was simply called

Mutul,[9] which is the reading of the "hair bundle"

Emblem Glyph seen in the accompanying photo above. Its precise meaning

remains obscure,[6] although some scholars think that it

is the hair knot of the Ahau or ruler.

Location

Map of the Maya area within the Mesoamerican region.

Both Tikal and Calakmul lie near the centre of the area.

The closest large modern settlements are Flores and Santa Elena,

approximately 64 kilometers (40 mi) by road to the southwest.[10]

Tikal is approximately 303 kilometers (188 mi) north of Guatemala

City. It is 19 kilometers (12 mi) south of the contemporary Maya

city of Uaxactun and 30 kilometers (19 mi) northwest of Yaxha.[6][11]

The city was located 100 kilometers (62

mi) southeast of its great Classic Period rival, Calakmul, and 85

kilometers (53 mi) northwest of Calakmul's ally Caracol, now in

Belize.[12]

The city has been completely mapped and covered an area greater than

16 square kilometers (6.2 sq mi) that included about 3000

structures.[13]

The topography of the site consists of a

series of parallel limestone ridges rising above swampy lowlands.

The major architecture of the site is clustered upon areas of higher

ground and linked by raised causeways spanning the swamps.[14]

The area around Tikal has been declared as the Tikal National

Park and the preserved area covers 570 square kilometers (220 sq

mi).[15]

The ruins lie among the tropical rainforests of northern Guatemala

that formed the cradle of lowland Maya civilization. The city itself

was located among abundant fertile upland soils, and may have

dominated a natural east—west trade route across the Yucatan

Peninsula.[16]

Conspicuous trees at the Tikal park

include:

-

gigantic kapok (Ceiba pentandra) the sacred tree of the

Maya

-

Tropical cedar (Cedrela odorata)

-

Honduras Mahogany (Swietenia

macrophylla)

Regarding the fauna, agouti, white-nosed coatis, gray

foxes, Geoffroy's spider monkeys, howler monkeys, harpy eagles,

falcons, ocellated turkeys, guans, toucans, green parrots and

leafcutter ants can be seen there regularly.

Jaguars, jaguarundis, and cougars are

also said to roam in the park. For centuries this city was

completely covered under jungle. The average annual rainfall at

Tikal is 1,945 millimeters (76.6 in).[17]

One of the largest of the Classic Maya cities, Tikal had no water

other than what was collected from rainwater and stored in ten

reservoirs. Archaeologists working in Tikal during the 20th century

refurbished one of these ancient reservoirs to store water for their

own use.[18]

The absence of springs, rivers, and

lakes in the immediate vicinity of Tikal highlights a prodigious

feat: building a major city with only supplies of stored seasonal

rainfall.

Tikal prospered with intensive agricultural techniques,

which were far more advanced than the slash and burn methods

originally theorized by archaeologists. The reliance on seasonal

rainfall left Tikal vulnerable to prolonged drought, which is

thought by some to have played a role in the Classic Maya Collapse.

The Tikal National Park covers an area of 575.83 square kilometers

(222.33 sq mi). It was created on 26 May 1955 under the auspices of

the Instituto de Antropología e Historia and was the first

protected area in Guatemala.[19]

Population

Population estimates for Tikal vary from 10,000 to as high as 90,000

inhabitants, with the most likely figure being at the upper end of

this range.[13]

Because of the low salt content of the Maya diet, it

is estimated that Tikal would have had to import 131 tons of salt

each year, based on a conservative population estimate of 45,000.[20]

The population of Tikal began a continuous curve of growth starting

in the Preclassic Period (approximately 2000 BC - AD 200), with a

peak in the Late Classic with the population growing rapidly from AD

700 through to 830, followed by a sharp decline. For the 120 square

kilometers (46 sq mi) area falling within the earthwork defenses of

the hinterland, the peak population is estimated at 517 per square

kilometer (1340 per square mile).

In an area within a 12 kilometers (7.5

mi) radius of the site core, peak population is estimated at

120,000; population density is estimated at 265 per square kilometer

(689 per square mile).

In a region within a 25 kilometers (16 mi)

radius of the site core and including some satellite sites, peak

population is estimated at 425,000 with a density of 216 per square

kilometer (515 per square mile). These population figures are even

more impressive because of the extensive swamplands that were

unsuitable for habitation or agriculture.

However, some archaeologists, such as

David Webster, believe these figures to be far too high.[21]

Rulers

|

Name (or

nickname)[23][24] |

Ruled |

Dynastic

succession no. |

Alternative Names |

|

Yax Ehb' Xook |

c.

90 |

1 |

Yax Moch Xok,

Yax Chakte'l Xok, First Scaffold Shark[25] |

|

Foliated Jaguar |

c.

292 |

? |

- |

|

Animal Headdress |

? |

10? |

Kinich Ehb'? |

|

Siyaj Chan K'awiil I |

c.

307 |

11 |

- |

|

Lady Une' B'alam |

c.

317 |

12? |

- |

|

K'inich Muwaan Jol I |

? -359 |

13 |

Mahk'ina Bird Skull,

Feather Skull |

|

Chak Tok Ich'aak I |

360-378 |

14 |

Jaguar Paw, Great

Paw, Great Jaguar Paw |

|

Yax Nuun Ayiin I |

379 -404? |

15 |

Curl Snout, Curl

Nose |

|

Siyaj Chan K'awiil

II |

411-456 |

16 |

Stormy Sky, Manikin

Cleft Sky |

|

Kan Chitam |

458-c. 486 |

17 |

Kan Boar, K'an Ak |

|

Chak Tok Ich'aak II |

c.

486-508 |

18 |

Jaguar Paw II,

Jaguar Paw Skull |

|

Lady of Tikal |

Kaloomte' B'alam |

c.

511-527+ |

19 |

Curl Head |

|

Bird Claw |

? |

20? |

Animal Skull I |

|

Wak Chan K'awiil |

537?-562 |

21 |

Double Bird |

|

Animal Skull |

c.

593-628 |

22 |

- |

|

K'inich Muwaan Jol

II |

c.

628-650 |

23 or 24 |

- |

|

Nuun Ujol Chaak |

c.

650-679 |

25 |

Shield Skull, Nun

Bak Chak |

|

Jasaw Chan K'awiil I |

682-734 |

26 |

Ruler A, Ah Cacao |

|

Yik'in Chan K'awiil |

734-c. 766 |

27 |

Ruler B, Yaxkin Caan

Chac, Sun Sky Rain |

|

Ruler 28 |

c.

766-768 |

28 |

- |

|

Yax Nuun Ayiin II |

768-c. 794 |

29 |

- |

|

Nuun Ujol K'inich |

c.

800? |

30? |

- |

|

Dark Sun |

-810+ |

31? |

- |

|

Jewel K'awiil |

-849+ |

? |

- |

|

Jasaw Chan K'awiil

II |

-869+ |

? |

- |

|

History

Preclassic

There are traces of early agriculture at the site dating as far back

as 1000 BC, in the Middle Preclassic.[26] A cache of

Mamon ceramics dating from about 700-400 BC were found in a sealed

chultun, a subterranean bottle-shaped chamber.[27]

Major construction at Tikal was already taking place in the Late

Preclassic period, first appearing around 400-300 BC, including the

building of major pyramids and platforms, although the city was

still dwarfed by sites further north such as El Mirador and Nakbe.[26][28]

At this time, Tikal participated in the widespread Chikanel culture

that dominated the Central and Northern Maya areas at this time - a

region that included the entire Yucatan Peninsula including northern

and eastern Guatemala and all of Belize.[29]

Two temples dating to Late Chikanel times had masonry-walled

superstructures that may have been corbel-vaulted, although this has

not been proven. One of these had elaborate paintings on the outer

walls showing human figures against a scrollwork background, painted

in yellow, black, pink and red.[30]

In the 1st century AD rich burials first appeared and Tikal

underwent a political and cultural florescence as its giant northern

neighbors declined.[26]

At the end of the Late Preclassic, the

Izapan style art and architecture from the Pacific Coast began to

influence Tikal, as demonstrated by a broken sculpture from the

acropolis and early murals at the city.[31]

Early Classic

Dynastic rulership among the

lowland Maya is most deeply rooted at Tikal. According to later

hieroglyphic records, the dynasty was founded by Yax-Moch-Xoc,

perhaps in the 3rd century AD.[32]

At the beginning of

the Early Classic, power in the Maya region was concentrated at

Tikal and Calakmul, in the core of the Maya heartland.[33]

Tikal may have benefited from the collapse of the large Preclassic

states such as El Mirador. In the Early Classic Tikal rapidly

developed into the most dynamic city in the Maya region, stimulating

the development of other nearby Maya cities.[34]

The site, however, was often at war and inscriptions tell of

alliances and conflict with other Maya states, including Uaxactun,

Caracol, Naranjo and Calakmul. The site was defeated at the end of

the Early Classic by Caracol, which rose to take Tikal's place as

the paramount centre in the southern Maya lowlands.[35]

The earlier part of the Early Classic saw hostilities between Tikal

and its neighbor Uaxactun, with Uaxactun recording the capture of

prisoners from Tikal.[36]

There appears to have been a breakdown in the male succession by AD

317, when Lady Une' B'alam conducted a katun-ending ceremony,

apparently as queen of the city.[37]

Tikal and Teotihuacan

The great metropolis of Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico

appears

to have decisively intervened in Tikal politics.

The eighth king of Tikal was Chak Tok Ich'aak (Great Jaguar Paw).[32]

Chak Tok Ich'aak built a palace that was preserved and

developed by later rulers until it became the core of the Central

Acropolis.[38]

Little is known about Chak Tok Ich'aak

except that he was killed on 14 January 378 AD. On the same day,

Siyah K’ak’ (Fire Is Born) arrived from the west, having passed

through El Peru, a site to the west of Tikal, on 8 January.[32]

On Stele 31 he is named as "Lord of the West".[39]

Siyah K’ak’ was probably a foreign

general serving a figure represented by a non-Maya hieroglyph of a

spearthrower combined with an owl, a glyph that is well known from

the great metropolis of Teotihuacan in the distant Valley of Mexico.

Spearthrower Owl may even have been the ruler of Teotihuacan.

These recorded events strongly suggest

that Siyah K’ak’ led a Teotihuacan invasion that defeated the native

Tikal king, who was captured and immediately executed.[40]

Siyah K'ak' appears to have been aided by a powerful political

faction at Tikal itself;[41] roughly at the time of the

conquest, a group of Teotihuacan natives were apparently residing

near the Lost World complex.[42]

He also exerted control over other

cities in the area, including Uaxactun, where he became king, but

did not take the throne of Tikal for himself.[26][43] Within a year,

the son of Spearthrower Owl by the name of Yax Nuun Ayiin I (First

Crocodile) had been installed as the tenth king of Tikal while he

was still a boy, being enthroned on 13 September 379.[43][44]

He reigned for 47 years as king of

Tikal, and remained a vassal of Siyah K'ak' for as long as the

latter lived. It seems likely that Yax Nuun Ayiin I took a wife from

the pre-existing, defeated, Tikal dynasty and thus legitimized the

right to rule of his son, Siyaj Chan K'awiil II.[43]

Río Azul, a small site 100 kilometers (62 mi) northeast of Tikal,

was conquered by the latter during the reign of Yax Nuun Ayiin I.

The site became an outpost of Tikal, shielding it from hostile

cities further north, and also became a trade link to the Caribbean.[45]

Although the new rulers of Tikal were foreign, their descendents

were rapidly Mayanised.

Tikal became the key ally and trading

partner of Teotihuacan in the Maya lowlands. After being conquered

by

Teotihuacan, Tikal rapidly dominated the northern and eastern Peten. Uaxactun, together with smaller towns in the region, were

absorbed into Tikal's kingdom. Other sites, such as Bejucal and

Motul de San José near Lake Petén Itzá became vassals of their more

powerful neighbor to the north.

By the middle of the 5th century Tikal

had a core territory of at least 25 kilometers (16 mi) in every

direction.[42]

Around the 5th century an impressive system of fortifications

consisting of ditches and earthworks was built along the northern

periphery of Tikal's hinterland, joining up with the natural

defenses provided by large areas of swampland lying to the east and

west of the city. Additional fortifications were probably also built

to the south.

These defenses protected Tikal's core

population and agricultural resources, encircling an area of

approximately 120 square kilometers (46 sq mi).[26]

Tikal and Copán

In the 5th century the power

of the city reached as far south as Copán, whose founder K'inich Yax

K'uk' Mo' was clearly connected with Tikal.[38]

Copán

itself was not in an ethnically Maya region and the founding of the

Copán dynasty probably involved the direct intervention of Tikal.[46]

K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' arrived in Copán in December 426 and bone

analysis of his remains shows that he passed his childhood and youth

at Tikal.[47]

An individual known as Ajaw K'uk' Mo'

(lord K'uk' Mo') is referred to in an early text at Tikal and may

well be the same person.[48] His tomb had Teotihuacan

characteristics and he was depicted in later portraits dressed in

the warrior garb of Teotihuacan. Hieroglyphic texts refer to him as

"Lord of the West", much like Siyah K’ak’.[47]

At the same time, in late 426, Copán

founded the nearby site of Quiriguá, possibly sponsored by Tikal

itself.[46] The founding of these two centers may have

been part of an effort to impose Tikal's authority upon the

southeastern portion of the Maya region.[49] The

interaction between these sites and Tikal was intense over the next

three centuries.[50]

A long-running rivalry between Tikal and Calakmul began in the 6th

century, with each of the two cities forming its own network of

mutually hostile alliances arrayed against each other in what has

been likened to a long-running war between two Maya superpowers. The

kings of these two capitals adopted the title kaloomte', a term that

has not been precisely translated but that implies something akin to

"high king".[51]

The early 6th century saw another queen ruling the city, known only

as the "Lady of Tikal", who was very likely a daughter of Chak Tok

Ich'aak II. She seems never to have ruled in her own right, rather

being partnered with male co-rulers.

The first of these was Kaloomte' B'alam,

who seems to have had a long career as a general at Tikal before

becoming co-ruler and 19th in the dynastic sequence. The Lady of

Tikal herself seems not have been counted in the dynastic numbering.

It appears she was later paired with

lord "Bird Claw", who is presumed to be the otherwise unknown 20th

ruler.[52]

Late Classic

Tikal hiatus

The main plaza, 2009

In the mid 6th century, Caracol seems to have allied with Calakmul

and defeated Tikal, closing the Early Classic.[53]

The

"Tikal hiatus" refers to a period between the late 6th to late 7th

century where there was a lapse in the writing of inscriptions and

large-scale construction at Tikal. In the latter half of the 6th

century AD a serious crisis befell the city, with no new stele

being erected and with widespread deliberate mutilation of public

sculpture.[54]

This hiatus in activity at Tikal was

long unexplained until later epigraphic decipherments identified

that the period was prompted by Tikal's comprehensive defeat at the

hands of Calakmul and the Caracol polity in AD 562, a defeat that

seems to have resulted in the capture and sacrifice of the king of

Tikal.[26] The badly eroded Altar 21 at Caracol described

how Tikal suffered this disastrous defeat in a major war in 562.

It

seems that Caracol was an ally of Calakmul in the wider conflict

between that city and Tikal, with the defeat of Tikal having a

lasting impact upon the city.[38]

Tikal was not sacked but its power and

influence were broken.[55] After its great victory,

Caracol grew rapidly and some of Tikal's population may have been

forcibly relocated there. During the hiatus period, at least one

ruler of Tikal took refuge with Janaab' Pakal of Palenque

(grandfather of

K'inich Janaab' Pakal), another

of Calakmul's victims.[56]

Calakmul itself thrived during

Tikal's long hiatus period.[57]

The beginning of the Tikal hiatus has served as a marker by which

archaeologists commonly sub-divide the Classic period of

Mesoamerican chronology into the

Early and Late Classic.[58]

Tikal and Dos Pilas

In 629 Tikal founded Dos Pilas, some 110 kilometers (68 mi) to the

southwest, as a military outpost in order to control trade along the

course of the Pasión River.[59]

B'alaj Chan K'awiil was installed on the

throne of the new outpost at the age of four, in 635, and for many

years served as a loyal vassal fighting for his brother, the king of

Tikal.[60] Roughly twenty years later Dos Pilas was

attacked by Calakmul and was soundly defeated. B'alaj Chan K'awiil

was captured by the king of Calakmul but, instead of being

sacrificed, he was re-instated on his throne as a vassal of his

former enemy,[61] and attacked Tikal in 657, forcing Nuun

Ujol Chaak, the then king of Tikal, to temporarily abandon the city.

The first two rulers of Dos Pilas

continued to use the Mutal emblem glyph of Tikal, and they probably

felt that they had a legitimate claim to the throne of Tikal itself.

For some reason, B'alaj Chan K'awiil was not installed as the new

ruler of Tikal; instead he stayed at Dos Pilas. Tikal

counterattacked against Dos Pilas in 672, driving B'alaj Chan

K'awiil into an exile that lasted five years.[62]

Calakmul tried to encircle Tikal within

an area dominated by its allies, such as El Peru, Dos Pilas and

Caracol.[63]

In 682, Jasaw Chan K'awiil erected the first dated monument at Tikal

in 120 years and claimed the title of kaloomte', so ending the

hiatus. He initiated a program of new construction and turned the

tables on Calakmul when, in 695, he captured the enemy king and

threw the enemy state into a long decline from which it never

recovered. After this, Calakmul never again erected a monument

celebrating a military victory.[56]

This defeat of Calakmul restored Tikal’s

pre-eminence in the Central Maya region, but never again in the

southwest Petén, where Dos Pilas maintained its presence.

Tikal after Teotihuacán

A vessel with jade inlays from the tomb of Jasaw Chan K'awiil I

beneath Temple I and bearing an effigy, probably that of the king.[64]

By the 7th century, there was no active Teotihuacan presence at any

Maya site and the centre of Teotihuacan had been razed by 700.

Even

after this, formal war attire illustrated on monuments was

Teotihuacan style.[65] Jasaw Chan K'awiil I and his heir

Yik'in Chan K'awiil continued hostilities against Calakmul and its

allies and imposed firm regional control over the area around Tikal,

extending as far as the territory around Lake Petén Itzá. These two

rulers were responsible for much of the impressive architecture

visible today.[66]

In 738, Quiriguá, a vassal of Copán, Tikal's key ally in the south,

switched allegiance to Calakmul, defeated Copán and gained its own

independence.[46] It appears that this was a conscious

effort on the part of Calakmul to bring about the collapse of

Tikal's southern allies.[67] This upset the balance of

power in the southern Maya area and lead to a steady decline in the

fortunes of Copán.[68]

In the 8th century, the rulers of Tikal collected monuments from

across the city and erected them in front of the North Acropolis.[69]

By the late 8th century and early 9th century, activity at Tikal

slowed.

Impressive architecture was still built but few hieroglyphic

inscriptions refer to later rulers.[66]

Terminal Classic

By the 9th century, the

crisis of the Classic Maya collapse was sweeping across the region,

with populations plummeting and city after city falling into

silence.[70]

Increasingly endemic warfare in the Maya

region caused Tikal's supporting population to heavily concentrate

close to the city itself, accelerating the use of intensive

agriculture and corresponding environmental decline.[71]

Construction continued at the beginning of the century, with the

erection of Temple 3, the last of the city's major pyramids and the

erection of monuments to mark the 19th K'atun in 810.[72]

The beginning of the 10th Bak'tun in 830

passed uncelebrated, and marks the beginning of a 60 year hiatus,

probably resulting from the collapse of central control in the city.[73]

During this hiatus, satellite sites traditionally under Tikal's

control began to erect their own monuments featuring local rulers

and using the Mutal emblem glyph, with Tikal apparently lacking the

authority or the power to crush these bids for independence.[66]

In 849, Jewel K'awiil is mentioned on a

stela at Seibal as visiting that city as the Divine Lord of Tikal

but he is not recorded elsewhere and Tikal's once great power was

little more than a memory. The sites of Ixlu and Jimbal had by now

inherited the once exclusive Mutal emblem glyph.[73]

As Tikal and its hinterland reached peak population, the area

suffered deforestation, erosion and nutrient loss followed by a

rapid decline in population levels. Tikal and its immediate

surroundings seem to have lost the majority of its population during

the period from 830 to 950 and central authority seems to have

collapsed rapidly.[21]

There is not much evidence from Tikal

that the city was directly affected by the endemic warfare that

afflicted parts of the Maya region during the Terminal Classic,

although an influx of refugees from the Petexbatún region may have

exacerbated problems resulting from the already stretched

environmental resources.[74]

The site core seen

from the south, with Temple I at centre,

the North Acropolis

to the left and Central Acropolis to the right

In the latter half of the 9th century

there was an attempt to revive royal power at the much diminished

city of Tikal, as evidenced by a stela erected in the Great Plaza by

Jasaw Chan K'awiil II in 869.

This was the last monument erected at

Tikal before the city finally fell into silence. The former

satellites of Tikal, such as Jimbal and Uaxactun, did not last much

longer, erecting their final monuments in 889. By the end of the 9th

century the vast majority of Tikal's population had deserted the

city, its royal palaces were occupied by squatters and simple

thatched dwellings were being erected in the city's ceremonial

plazas.

The squatters blocked some doorways in

the rooms the reoccupied in the monumental structures of the site

and left rubbish that included a mixture of domestic refuse and

non-utilitarian items such as musical instruments. These inhabitants

reused the earlier monuments for their own ritual activities far

removed from those of the royal dynasty that had erected them.

Some monuments were vandalized and some

were moved to new locations.

Before its final abandonment all

respect for the old rulers had disappeared, with the tombs of the

North Acropolis being explored for jade and the easier to find tombs

being looted. After 950, Tikal was all but deserted, although a

remnant population may have survived in perishable huts interspersed

among the ruins. Even these final inhabitants abandoned the city in

the 10th or 11th centuries and the rainforest claimed the ruins for

the next thousand years.

Some of Tikal's population may have

migrated to the Peten Lakes region, which remained heavily populated

in spite of a plunge in population levels in the first half of the

9th century.[21][73][74]

The most likely cause of collapse at Tikal is overpopulation and

agrarian failure. The fall of Tikal was a blow to the heart of

Classic Maya civilization, the city having been at the forefront of

courtly life, art and architecture for over a thousand years, with

an ancient ruling dynasty.[75]

Modern history

In 1525, the Spanish

conquistador Hernán Cortés passed within a few kilometers of the

ruins of Tikal but did not mention them in his letters.[76]

As is often the case with huge ancient ruins, knowledge of the site

was never completely lost in the region. It seems that local people

never forgot about Tikal and they guided Guatemalan expeditions to

the ruins in the 1850s.[16]

Some second- or third-hand accounts of

Tikal appeared in print starting in the 17th century, continuing

through the writings of John Lloyd Stephens in the early 19th

century (Stephens and his illustrator Frederick Catherwood heard

rumors of a lost city, with white building tops towering above the

jungle, during their 1839-40 travels in the region).

Because of the site's remoteness from

modern towns, however, no explorers visited Tikal until Modesto Méndez and

Ambrosio Tut, respectively the commissioner and the

governor of Petén, visited it in 1848. Artist Eusebio Lara

accompanied them and their account was published in Germany in 1853.[77]

Several other expeditions came to further investigate, map, and

photograph Tikal in the 19th century (including Alfred P. Maudslay

in 1881-82) and the early 20th century.

Pioneering archaeologists started to

clear, map and record the ruins in the 1880s.[16]

In 1951, a small airstrip was built at the ruins,[15]

which previously could only be reached by several days’ travel

through the jungle on foot or mule. In 1956 the Tikal project began

to map the city on a scale not previously seen in the Maya area.[78]

From 1956 through 1970, major archaeological excavations were

carried out by the University of Pennsylvania Tikal Project.[79]

They mapped much of the site and

excavated and restored many of the structures.[16]

Excavations directed by Edwin Shook and later by

William Coe of the

University investigated the North Acropolis and the Central Plaza

from 1957 to 1969.[80] The Tikal Project recorded over

200 monuments at the site.[16] In 1979, the Guatemalan

government began a further archeological project at Tikal, which

continued through to 1984.[79]

Filmmaker George Lucas used Tikal as a setting in his first Star

Wars movie, Episode IV: A New Hope, released in 1977.[81][82]

Temple I at Tikal was featured on the reverse of the 50 centavo

banknote.[83]

Tikal is now a major tourist attraction surrounded by its own

national park.[16]

A site museum has been built at Tikal;

it was completed in 1964.[84]

The site

Map of the site core

Tikal has been partially restored by the

University of Pennsylvania and the government of Guatemala.[44] It

was one of the largest of the Classic period Maya cities and was one

of the largest cities in the Americas.[85]

The architecture of the ancient city is

built from limestone and includes the remains of temples that tower

over 70 meters (230 ft) high, large royal palaces, in addition to a

number of smaller pyramids, palaces, residences, administrative

buildings, platforms and inscribed stone monuments.[9][86]

There is even a building which seemed to have been a jail,

originally with wooden bars across the windows and doors. There are

also seven courts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame, including a

set of 3 in the Seven Temples Plaza, a unique feature in

Mesoamerica.

The limestone used for construction was local and quarried on-site.

The depressions formed by the extraction of stone for building were

plastered to waterproof them and were used as reservoirs, together

with some waterproofed natural depressions.

The main plazas were

surfaced with stucco and laid at a gradient that channeled rainfall

into a system of canals that fed the reservoirs.[87]

The residential area of Tikal covers an estimated 60 square

kilometers (23 sq mi), much of which has not yet been cleared,

mapped, or excavated. A huge set of earthworks has been discovered

ringing Tikal with a 6-metre (20 ft) wide trench behind a rampart.

The 16 square kilometers (6.2 sq mi) area around the site core has

been intensively mapped;[66] it may have enclosed an area

of some 125 square kilometers (48 sq mi) (see below).

Population estimates place the

demographic size of the site between 10,000 and 90,000, and possibly

425,000 in the surrounding area.

Recently, a project exploring the

defensive earthworks has shown that the scale of the earthworks is

highly variable and that in many places it is inconsequential as a

defensive feature. In addition, some parts of the earthwork were

integrated into a canal system.

The earthwork of Tikal varies

significantly in coverage from what was originally proposed and it

is much more complex and multifaceted than originally thought.[88]

Causeways

By the Late Classic, a network of sacbeob (causeways) linked various

parts of the city, running for several kilometers through its urban

core.

These linked the Great Plaza with Temple

4 (located about 750 meters (2,500 ft) to the west) and the Temple

of the Inscriptions (about 1 kilometer (0.62 mi) to the southeast).[89]

These broad causeways were built of packed and plastered

limestone and have been named after early explorers and

archaeologists; the Maler, Maudslay, Tozzer and Méndez causeways.

They assisted the passage everyday

traffic during the rain season and also served as dams.[14]

-

The Maler Causeway runs north

from behind Temple I to Group H. A large bas-relief is

carved onto limestone bedrock upon the course of the

causeway just south of Group H. It depicts two bound

captives and dates to the Late Classic.[90]

-

The Maudsley Causeway runs 0.8

kilometers (0.50 mi) northeast from Temple IV to Group H.[90]

-

The Mendez Causeway runs

southeast from the East Plaza to Temple VI, a distance of

about 1.3 kilometers (0.81 mi).[77][91]

-

The Tozzer Causeway runs west

from the Great Plaza to Temple IV.[92]

Architectural groups

The North Acropolis

The Great Plaza lies at the

core of the site; it is flanked on the east and west sides by two

great temple-pyramids. On the north side it is bordered by the North

Acropolis and on the south by the Central Acropolis.[85]

The Central Acropolis is a palace complex just south of the Great

Plaza.[85]

The North Acropolis, together with the Great Plaza immediately to

the south, is one of the most studied architectural groups in the

Maya area; the Tikal Project excavated a massive trench across the

complex, thoroughly investigating its construction history. It is a

complex group with construction beginning in the Preclassic Period,

around 350 BC.

It developed into a funerary complex for

the ruling dynasty of the Classic Period, with each additional royal

burial adding new temples on top of the older structures. After AD

400 a row of tall pyramids was added to the earlier Northern

Platform, which measured 100 by 80 meters (330 by 260 ft), gradually

hiding it from view.

Eight temple pyramids were built in the

6th century AD, each of them had an elaborate roof-comb and a

stairway flanked by masks of the gods. By the 9th century AD, 43

stele and 30 altars had been erected in the North Acropolis; 18 of

these monuments were carved with hieroglyphic texts and royal

portraits. The North Acropolis continued to receive burials into the

Postclassic Period.[80][87]

The South Acropolis is found next to Temple V.

It was built upon a

large basal platform that covers an area of more than 20,000 square

meters (220,000 sq ft).[14]

Temples I, II, III and V as seen from Temple IV

The Plaza of the Seven Temples is to the west of the South

Acropolis. It is bordered on the east side by a row of nearly

identical temples, by palaces on the south and west sides and by an

unusual triple ball-court on the north side.[14][93]

Group G lies just south of the Mendez Causeway. The complex dates to

the Late Classic and consists of palace-type structures and is one

of the largest groups of its type at Tikal. It has two stories but

most of the rooms are on the lower floor, a total of 29 vaulted

chambers. The remains of two further chambers belong to the upper

storey. One of the entrances to the group was framed by a gigantic

mask.[77]

Group H is centered on a large plaza to the north of the Great

Plaza. It is bordered by temples dating to the Late Classic.[90]

There are nine Twin-Pyramid Complexes at Tikal, one of which was

completely dismantled in ancient times and some others were partly

destroyed. They vary in size but consist of two pyramids facing each

other on an east-west axis.[90] These pyramids are

flat-topped and have stairways on all four sides.

A row of plain stele is placed

immediately to the west of the eastern pyramid and to the north of

the pyramids, and lying roughly equidistant from them, there is

usually a sculpted stela and altar pair.

On the south side of these

complexes there is a long vaulted building containing a single room

with nine doorways. The entire complex was built at once and these

complexes were built at 20 year (or k'atun) intervals during the

Late Classic.[77]

The first Twin Pyramid Complex was built

in the early 6th century in the East Plaza.

It was once thought that

these complexes were unique to Tikal but rare examples have now been

found at other sites, such as Yaxha and Ixlu, and they may reflect

the extent of Tikal's political dominance in the Late Classic.[94]

Group Q is a twin-pyramid complex, and is one of the largest at

Tikal. It was built by Yax Nuun Ayiin II in 771 in order to mark the

end of the 17th K'atun.[94] Most of it has been restored

and its monuments have been re-erected.[77]

Group R is another twin-pyramid complex, dated to 790. It is close

to the Maler Causeway.[77]

Structures

Temple II on the main

plaza

There are thousands of ancient

structures at Tikal and only a fraction of these have been

excavated, after decades of archaeological work.

The most prominent surviving buildings

include six very large Mesoamerican step pyramids, labeled Temples

I - VI, each of which support a temple structure on their summits.

Some of these pyramids are over 60 meters high (200 feet). They were

numbered sequentially during the early survey of the site. It is

estimated that each of these major temples could have been built in

as little as two years.[95]

The majority of pyramids currently visible at Tikal were built

during Tikal’s resurgence following the Tikal Hiatus (i.e., from the

late 7th to the early 9th century).

It should be noted, however,

that the majority of these structures contain sub-structures that

were initially built prior to the hiatus.

-

Temple I (also known as the Temple of Ah Cacao or Temple of the

Great Jaguar) is a funerary pyramid dedicated to Jasaw Chan K'awil,

who was entombed in the structure in AD 734,[80][85] the

pyramid was completed around 740-750.[96] The temple

rises 47 metres (150 ft) high.[1]

The massive roof-comb

that topped the temple was originally decorated with a giant

sculpture of the enthroned king, although little of this decoration

survives.[97]

The tomb of the king was discovered by

Aubrey Trik of the University of Pennsylvania in 1962.[18]

Among items recovered from the Late Classic tomb were a large

collection of inscribed human and animal bone tubes and strips with

sophisticated scenes depicting deities and people, finely carved and

rubbed with vermilion, as well as jade and shell ornaments and

ceramic vessels filled with offerings of food and drink.[18][98]

The shrine at the summit of the pyramid has three chambers,

each behind the next, with the doorways spanned by wooden lintels

fashioned from multiple beams.

The outermost lintel is plain but the

two inner lintels were carved, some of the beams were removed in the

19th century and their location is unknown, while others were taken

to museums in Europe.[95]

-

Temple II (also known as the Temple of the Mask) in was built around

AD 700 and stands 38 meters (120 ft) high. Like other major temples

at Tikal, the summit shrine had three consecutive chambers with the

doorways spanned by wooden lintels, only the middle of which was

carved.

The temple was dedicated to the wife of Hasaw Chan K'awil,

although no tomb was found. The queen's portrait was carved into the

lintel spanning the doorway of the summit shrine.

One of the beams

from this lintel is now in the American Museum of Natural History in

New York.[69][99]

-

Temple III (also known as the Temple of the Jaguar Priest) was the

last of the great pyramids to be built at Tikal. It stood 55 meters

(180 ft) tall and contained an elaborately sculpted but damaged roof

lintel, possibly showing Dark Sun engaged in a ritual dance around

AD 810.[72]

The temple shrine possesses two chambers.[100]

The elaborately carved wooden Lintel 3 from Temple IV.

It celebrates

a military victory by Yik'in Chan K'awiil in 743.[101]

-

Temple IV is the tallest temple-pyramid at Tikal, measuring 70

meters (230 ft) from the plaza floor level to the top of its roof

comb.[85]

Temple IV marks the reign of Yik’in Chan Kawil

(Ruler B, the son of Ruler A or Jasaw Chan K'awiil I) and two carved

wooden lintels over the doorway that leads into the temple on the

pyramid’s summit record a long count date (9.15.10.0.0) that

corresponds to C.E. 741 (Sharer 1994:169).

Temple IV is the largest pyramid built

anywhere in the Maya region in the 8th century,[102] and

as it currently stands is the tallest pre-Columbian structure in the

Americas although the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan may

originally have been taller, as may have been one of the structures

at El Mirador.[103]

-

Temple V stands almost 190 feet (58 m) tall and is still covered

with vegetation.[99]

-

Temple VI is also known as the Temple of the Inscriptions and was

dedicated in AD 766. It is notable for its 12-metre (39 ft) high

roof-comb. Panels of hieroglyphs cover the back and sides of the

roof-comb. The temple faces onto a plaza to the west and its front

is unrestored.[77]

-

Temple 33 is a funerary pyramid erected over the tomb of Siyaj Chan

K'awiil I (known as Burial 48) in the North Acropolis. It started

life in the Early Classic as a wide basal platform decorated with

large stucco masks that flanked the stairway.

Later in the Early

Classic a new superstructure was added, with its own masks and

decorated panels.

During the Hiatus a third stage was

built over the earlier constructions, the stairway was demolished

and another royal burial, of an unidentified ruler, was set into the

structure (Burial 23).

While the new pyramid was being built another

high ranking tomb (Burial 24) was inserted into the rubble core of

the building. The pyramid was then completed, standing 33 meters

(110 ft) tall.[104]

-

Structure 34 is a pyramid in the North Acropolis that was built by Siyaj Chan K'awiil II over the tomb of his father, Yax Nuun Ayiin I.

The pyramid was topped by a three chambered shrine, the rooms

situated one behind the other.[102]

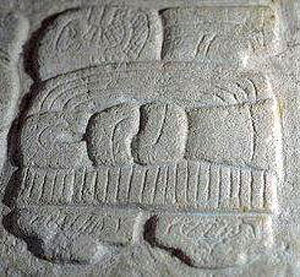

Detail of Teotihuacan-related imagery decorating the sloping talud

sections

of the talud-tablero sides of Structure 5D-43.[105]

-

Structure 5D-43 is an unusual radial temple in the East Plaza, built

over a pre-exiting twin pyramid complex. It is built into the end of

the East Plaza Ballcourt and possessed four entry doorways and three

stairways, the fourth (south) side was too close to the Central

Acropolis for a stairway on that side.[106]

The building has a talud-tablero platform profile, modified from the original style

found at Teotihuacan.

In fact, it has been suggested that the

style of the building has closer affinities with El Tajin and

Xochicalco than with Teotihuacan itself. The vertical tablero panels

are set between sloping talud panels and are decorated with paired

disc symbols. Large flower symbols are set into the sloping talud

panels, related to the Venus and star symbols used at Teotihuacan.

The roof of the structure was decorated

with friezes although only fragments now remain, showing a monstrous

face, perhaps that of a jaguar, with another head emerging from the

mouth.[105] The second head possesses a bifurcated tongue

but is probably not that of a snake.[107]

The temple, and its associated ball-court,

probably date to the reign of Nuun Ujol Chaak or that of his son

Jasaw Chan K'awiil I, in the later part of the 7th century.[108]

-

Structure 5C-49 possesses a clear Teotihuacan-linked architectural

style; it has balustrades, an architectural feature that is very

rare in the Maya region, and a talud-tablero facade; it dates to the

4th century AD.[109] It is located near to the Lost World pyramid.[110]

-

Structure 5C-53 is a small Teotihuacan-style platform that dates to

about AD 600. It had stairways on all four sides and did not possess

a superstructure.[100]

A large stucco mask

adorning the substructure of Temple 33

-

The Lost World Pyramid (Structure 5C-54)

lies in the southwest portion of Tikal’s central core, south of

Temple III and west of Temple V.[89][91][111]

It was decorated with stucco masks of

the sun god and dates to the Late Preclassic;[14] this

pyramid is part of an enclosed complex of structures that remained

intact and un-impacted by later building activity at Tikal.

By the end of the Late Preclassic this

pyramid was one of the largest structures in the Maya region.[89]

It attained its final form during the reign of Chak Tok Ich'aak in

the 4th century AD, in the Early Classic, standing more than 30

meters (98 ft) high with stairways on all four sides and a flat top

that possibly supported a superstructure built from perishable

materials.[109][112]

Although the plaza later suffered

significant alteration, the organization of a group of temples on

the east side of this complex adheres to the layout that defines the

so-called E-Groups, identified as solar observatories.[113]

-

Structure 5D-96 is the central temple on the east side of the Plaza

of the Seven Temples. It has been restored and its rear outer wall

is decorated with skull-and-crossbones motifs.[114]

-

Group 6C-16 is an elite residential complex that has been thoroughly

excavated. It lies a few hundred meters south of the Lost World

Complex and the excavations have revealed elaborate stucco masks,

ballplayer murals, relief sculptures and buildings with Teotihuacan

characteristics.[109]

-

The Great Plaza Ballcourt is a small ball-court that lies between

Temple I and the Central Acropolis.[99]

-

The Bat Palace is also known as the Palace of Windows and lies to

the west of Temple III.[115] It has two stories, with a

double range of chambers on the lower storey and a single range in

the upper storey, which has been restored. The palace has ancient

graffiti and possesses low windows.[100]

-

Complex N lies to the west of the Bat Palace and Temple III. The

complex dates to AD 711.[116]

Altars

-

Altar 5 is carved with two nobles, one of whom is probably Jasaw

Chan K'awiil I. They are performing a ritual using the bones of an

important woman.[117] Altar 5 was found in Complex N,

which lies to the west of Temple III.[118]

-

Altar 8 is sculpted with a bound captive.[119] It was

found within Complex P in Group H and is now in the Museo Nacional

de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City.[90]

-

Altar 9 is associated with Stela 21 and bears the sculpture of a

bound captive. It is located in front of Temple VI.[77]

-

Altar 10 is carved with a captive tied to a scaffold.[119]

It is in

the northern enclosure of Group Q, a twin-pyramid complex and has

suffered from erosion.[77]

Lintels

At Tikal, beams of sapodilla wood were placed as lintels spanning

the inner doorways of temples. These are the most elaborately carved

wooden lintels to have survived anywhere in the Maya region.[120]

Lintel 3 from Temple IV was taken to Basel in Switzerland in the

19th century. It was in almost perfect condition and depicts Yik'in

Chan K'awiil seated on a palanquin.[121]

Stelae

Stelae are carved stone shafts, often sculpted with figures and

hieroglyphs.

A selection of the most notable stele at Tikal

follows:

-

Stela 1 dates to the 5th century and depicts the king Siyaj Chan

K'awiil II in a standing position.[122]

-

Stela 4 is dated to AD 396, during the reign of Yax Nuun Ayiin after

the conquest of Tikal by Teotihuacan.[123] The stela

displays a mix of Maya and Teotihuacan qualities, and deities from

both cultures. It has a portrait of the king with the Underworld

Jaguar God under one arm and the Mexican Tlaloc under the other. His

helmet is a simplified version of the Teotihuacan War Serpent.

Unusually for Maya sculpture, but typically for Teotihuacan, Yax

Nuun Ayiin is depicted with a frontal face, rather than in profile.[124]

-

Stela 5 was dedicated in 744 by Yik'in Chan K'awiil.[126]

-

Stela 6 is a badly damaged monument dating to 514 and bears the name

of the "Lady of Tikal" who celebrated the end of the 4th K'atun in

that year.[127]

-

Stela 10 is twinned with Stela 12 but is badly damaged. It described

the accession of Kaloomte' B'alam in the early 6th century and

earlier events in his career, including the capture of a prisoner

depicted on the monument.[128]

-

Stela 11 was the last monument ever erected at Tikal; it was

dedicated in 869 by Jasaw Chan K'awiil II.[73]

-

Stela 12 is linked to the queen known as the "Lady of Tikal" and

king Kaloomte' B'alam. The queen is described as performing the

year-ending rituals but the monument was dedicated in honour of the

king.[52]

-

Stela 16 was dedicated in 711, during the reign of Jasaw Chan

K'awiil I. The sculpture, including a portrait of the king and a

hieroglyphic text, are limited to the front face of the monument.[126]

It was found in Complex N, west of Temple III.[118]

-

Stela 19 was dedicated in 790 by Yax Nuun Ayiin II.[126]

-

Stela 20 was found in Complex P, in Group H, and was moved to the

Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City.[90]

-

Stela 21 was dedicated in 736 by Yik'in Chan K'awiil.[126]

Only the bottom of the stela is intact, the rest having been

mutilated in ancient times. The surviving sculpture is of fine

quality, consisting of the feet of a figure and of accompanying

hieroglyphic text. The stela is associated with Altar 9 and is

located in front of Temple VI.[77]

-

Stela 22 was dedicated in 771 by Yax Nuun Ayiin II in the northern

enclosure of Group Q, a twin-pyramid complex.[126] The

face of the figure on the stela has been mutilated.[77]

-

Stela 23 was broken in antiquity and was re-erected in a residential

complex. The defaced portrait on the monument is that of the

so-called "Lady of Tikal", a daughter of Chak Tok Ich'aak II who

became queen at the age of six but never ruled in her own right,

being paired with male co-rulers. It dates to the early 6th century.[127]

-

Stela 24 was erected at the foot of Temple 3 in 810, accompanied by

Altar 7. Both were broken into fragments in ancient times, although

the name of Dark Sun survives on three fragments.[72]

-

Stela 29 bears a Long Count date equivalent to AD 292, the earliest

surviving Long Count date from the Maya lowlands.[37] The

stela is also the earliest monument to bear the Tikal emblem glyph.

It bears a sculpture of the king facing to the right, holding the

head of an underworld jaguar god, one of the patron deities of the

city. The stela was deliberately smashed during the 6th century or

some time later, the upper portion was dragged away and dumped in a

rubbish tip close to Temple III, to be uncovered by archaeologists

in 1959.[129][130]

-

Stela 30 is the first surviving monument to be erected after the

Hiatus. Its style and iconography is similar to that of Caracol, one

of the more important of Tikal's enemies.[126]

-

Stela 31 is the accession monument of Siyah Chan K'awil II, also

bearing two portraits of his father, Yax Nuun Ayiin, as a youth

dressed as a Teotihuacan warrior. He carries a spear-thrower in one

hand and bears a shield decorated with the face of Tlaloc, the

Teotihuacan war god.[131]

In ancient times the sculpture

was broken and the upper portion was moved to the summit of Temple

33 and ritually buried.[132]

Stela 31, with the sculpted image of Siyah Chan K'awil II.

[125]

Stela 31 has been described as the

greatest Early Classic sculpture

to survive at Tikal. A long

hieroglyphic text is carved onto the back of the monument, the

longest to survive from the Early Classic,[125] which

describes the arrival of Siyah K'ak' at El Peru and Tikal in January

378.[39]

It was also the first stela as Tikal to be

carved on all four faces.[133]

-

Stela 32 is a fragmented monument with a foreign Teotihuacan-style

sculpture apparently depicting the lord of that city with the

attributes of the central Mexican storm god Tlaloc, including his

goggle eyes and tasseled headdress.[134]

-

Stela 39 is a broken monument that was erected in the Lost World

complex. The upper portion of the stela is missing but the lower

portion shows the lower body and legs of Chak Tok Ich'aak, holding a

flint axe in his left hand. He is trampling the figure of a bound,

richly dressed captive. The monument is dated to AD 376. The text on

the back of the monument describes a bloodletting ritual to

celebrate a Katun-ending.[112] The stela also names Chak

Tok Ich'aak I's father as K'inich Muwaan Jol.[37]

-

Stela 40 bears a portrait of Kan Chitam and dates to AD 468.[135]

Burials

A ceramic censer representing an elderly deity,

found in Burial 10.[136]

-

Burial 1 is a tomb in the Lost World complex. A fine ceramic bowl

was recovered from the tomb, with the handle formed from

three-dimensional head and neck of a bird emerging from the

two-dimensional body painted on the lid.[137]

-

Burial 10 is the tomb of Yax Nuun Ayiin.[32] It is

located beneath Structure 34 in the North Acropolis. The tomb

contained a rich array of offerings, including ceramic vessels and

food, and nine youths were sacrificed to accompany the dead king.[102]

A dog was also entombed with the deceased king. Pots in the tomb

were stuccoed and painted and many demonstrated a blend of Maya and

Teotihuacan styles.[132]

Among the offerings was an

incense-burner in the shape of an elderly underworld god, sitting on

a stool made of human bones and holding a severed head in his hands.[138]

The tomb was sealed with a corbel vault, then the pyramid was built

on top.[102]

-

Burial 48 is generally accepted as the tomb of Siyah Chan K'awil. It

is located beneath Temple 33 in the North Acropolis.[104][139]

The chamber of the tomb was cut from the bedrock and contained the

remains of the king himself together with those of two adolescents

who had been sacrificed in order to accompany the deceased ruler.[139]

The walls of the tomb were covered with

white stucco painted with hieroglyphs that included the Long Count

date equivalent to 20 March 457, probably the date of either the

death or interment of the king.[54] The king's skeleton

was missing its skull, its femurs and one of its hands while the

skeletons of the sacrificial victims were intact.[98]

-

Burial 85 dates to the Late Preclassic and was enclosed by a

platform, with a primitive corbel vault. The tomb contained a single

male skeleton, which lacked a skull and its thighbones.[25][30]

The dynastic founder of Tikal, Yax Ehb'

Xook, has been linked to this tomb, which lies deep in the heart of

the North Acropolis.[25] The deceased had probably died

in battle with his body being mutilated by his enemies before being

recovered and interred by his followers. The bones were wrapped

carefully in textiles to form an upright bundle.[140]

The missing head was replaced by a small

greenstone mask with shell-inlaid teeth and eyes and bearing a

three-pointed royal headband.[25][141] This head wears an

emblem of rulership on its forehead and is a rare Preclassic lowland

Maya portrait of a king.[53] Among the contents of the

tomb were a stingray spine, a spondylus shell and twenty-six ceramic

vessels.[141]

-

Burial 116 is the tomb of Jasaw Chan K'awiil I. It is a large

vaulted chamber deep within the pyramid, below the level of the

Great Plaza.

The tomb contained rich offerings of

jadeite, ceramics, shell and works of art. The body of the king was

covered with large quantities of jade ornaments including an

enormous necklace with especially large beads, as depicted in

sculpted portraits of the king. One of the outstanding pieces

recovered from the tomb was an ornate jade mosaic vessel with the

lid bearing a sculpted portrait of the king himself.[142]

-

Burial 195 was flooded with mud in antiquity. This flood had covered

wooden objects that had completely rotted away by the time the tomb

was excavated, leaving hollows in the dried mud. Archaeologists

filled these hollows with stucco and thus excavated four effigies of

the god K'awiil, the wooden originals long gone.[143][144]

-

Burial 196 is a Late Classic royal tomb that contained a jade mosaic

vessel topped with the head of the Maize God.[13]

Notes

|

1. Martin & Grube

2000, p.47.

2. UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

3. Sharer & Traxler 2006, p.1. Hammond 2000, p.233.

4. Martin & Grube 2008, pp.29-32.

5. Adams 2000, p.34.

6. Martin & Grube 2000, p.30.

7. Drew 1999, p.136.

8. Schele & Mathews 1999, p.64.

9. Sharer & Traxler 2006, p.1.

10. Kelly 1996, pp.111-2.

11. Webster 2002, p.118.

12. Webster 2002, pp.188, 192.

13. Coe 1999, p.104.

14. Drew 1999, p.185.

15. Kelly 1996, p.140.

16. Webster 2002, p.261.

17. Webster 2002, p.239.

18. Coe 1999, p.124.

19. Torres.

20. Coe 1999, p.30.

21. Webster 2002, p.264.

22. Martin & Grube 2000, p.25.

23. Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp.310-2

24. Martin & Grube 2000 pp.26-52.

25. Drew 1999, p.187.

26. Webster 2002, p.262.

27. Coe 1999, p.55.

28. Coe 1999, p.73.

29. Coe 1999, pp.73, 80.

30. 1999, p.75.

31. Coe 1999, p.78.

32. Coe 1999, p.90.

33. Miller 1999, pp.88-9.

34. Webster 2002, p.191.

35. Sharer 1994, p.265.

36. Kelly 1996, p.129.

37. Martin & Grube 2000, p.27.

38. Webster 2002, p.192.

39. Drew 1999, p.199.

40. Coe 1999, pp.90-1.

41. Webster 2002, p.133.

42. Drew 1999, p.201.

43. Drew 1999, p.200.

44. Coe 1999, p.97.

45. Drew 1999, pp.201-2.

46. Wyllys Andrews & Fash 2005, p.407.

47. Fash & Agurcia Fasquelle 2005, p.26.

48. Looper 2003, p.37.

49. Looper 2003, p.38. |

50. Looper 1999, p.263.

51. Webster 2002, pp.168-9.

52. Martin & Grube 2000, pp.38-9.

53. Miller 1999, p.89.

54. Coe 1999, p.94.

55. Webster 2002, pp.192-3.

56. Webster 2002, p.193.

57. Webster 2002, p.194.

58. Miller and Taube 1993, p.20.

59. Salisbury et al 2002, p.1.

60. Salisbury et al 2002, pp.2-3.

61. Salisbury et al 2002, p.2.

62. Webster 2002, p.276.

63. Hammond 2000, p.220.

64. Webster 2002, pl.13.

65. Miller 1999, p.105.

66. Webster 2002, p.263.

67. Looper 2003, p.79.

68. Wyllys Andrews & Fash 2005, p.408.

69. Miller 1999, p.33.

70. Martin & Grube 2000, pp.52-3.

71. Webster 2002, p.340.

72. Martin & Grube 2000, p.52.

73. Martin & Grube 2000, p.53.

74. Webster 2002, p.273.

75. Webster 2002, p.274.

76. Webster 2002, pp.83-4.

77. Kelly 1996, p.139.

78. Adams 2000, p.19.

79. Adams 2000, p.30.

80. Martin & Grube 2000, p.43.

81. Webster 2002, p.29.

82. StarWars.com

83. Banco de Guatemala.

84. Coe 1967, 1988, p.10.

85. Coe 1999, p.123.

86. Drew 1999, p.183.

87. Drew 1999, p.186.

88. Martínez et al 2004, pp.639-640.

89. Hammond 2000, p.227.

90. Kelly 1996, p.138.

91. Martin & Grube 2000, p.24.

92. Sharer & Traxler 2006, p.302.

93. Sharer & Traxler 2006, p.304.

94. Martin & Grube 2000, p.51.

95. Kelly 1996, p.133.

96. Webster 2002, pl.15.

97. Miller 1999, p.27.

98. Miller 1999, p.78.

99. Kelly 1996, p.134.

|

100. Kelly 1996, p.136.

101. Miller 1999, p.13.

102. Miller 1999, p.32.

103. Kelly 1996, p.137.

104. Martin & Grube 2000, p.36.

105. Schele & Mathews 1999, p.72.

106. Schele & Mathews 1999, p.71.

107. Schele & Mathews 1999, pp.72-3.

108. Schele & Mathews 1999, pp.70-1.

109. Hammond 2000, p.228.

110. Miller 1999, p.30.

111. Kelly 1996, p.130.

112. Drew 1999, p.188.

113. Hammond 2000, pp.227-8.

114. Kelly 1996, p.135.

115. Kelly 1996, pp.130, 136.

116. Kelly 1996, pp. 136-7.

117. Webster 2002, pl.14.

118. Kelly 1996, p.137.

119. Miller 1999, p.130.

120. Miller 1999, pp.130-1.

121. Miller 1999, p.131.

122. Miller 1999, p.153.

123. Miller 1999, p.94.

124. Miller 1999, p.95.

125. Miller 1999, p.97.

126. Miller 1999, p.129.

127. Martin & Grube 2000, p.38.

128. Martin & Grube 2000, p.39.

129. Miller 1999, p.91.

130. Drew 1999, pp.187-8.

131. Coe 1999, pp.91-2.

132. Miller 1999, p.96.

133. Miller 1999, p.98.

134. Martin & Grube 2000, p.31.

135. Martin & Grube 2000, p.37.

136. Martin & Grube 2000, p.33.

137. Miller 1999, pp.193-4.

138. Drew 1999, p.197.

139. Coe 1999, p.91.

140. Coe 1999, pp.75-6.

141. Coe 1999, p.76.

142. Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp.397-399.

143. Martin & Grube 2000, p.41.

144. Miller 1999, p.216.

|

References

-

Adams, Richard E.W. (2000).

"Introduction to a Survey of the Native Prehistoric Cultures of

Mesoamerica". in Richard E.W. Adams and Murdo J. Macleod (eds.).

The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas,

Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press. pp. 1-44. ISBN 0-521-35165-0. OCLC 33359444.

-

Andrews, E. Wyllys; and William L.

Fash (2005). "Issues in Copán Archaeology". in E. Wyllys Andrews

and William L. Fash (eds.). Copán: The History of an Ancient

Maya Kingdom. Santa Fe and Oxford: School of American Research

Press and James Currey Ltd. pp. 395-425. ISBN 0-85255-981-X.

OCLC 56194789.

-

Banco de Guatemala. "Monedas". Banco

de Guatemala. http://www.banguat.gob.gt/inc/ver.asp?id=/monedasybilletes/ilustraciones-11-denominaciones.htm&e=40306.

Retrieved 2009-11-13. (Spanish)

-

Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya.

Ancient peoples and places series (6th edition, fully revised

and expanded ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN

0-500-28066-5. OCLC 59432778.

-

Coe, William R. (1967, 1988). Tikal:

Guía de las Antiguas Ruinas Mayas. Guatemala: Piedra Santa. ISBN

84-8377-246-9. (Spanish)

-

Drew,David (1999). The Lost

Chronicles of the Mayan Kings. Los Angeles: University of

California Press.

-

Fash, William L.; and Ricardo

Agurcia Fasquelle (2005). "Contributions and Controversies in

the Archaeology and History of Copán". in E. Wyllys Andrews and

William L. Fash (eds.). Copán: The History of an Ancient Maya

Kingdom. Santa Fe and Oxford: School of American Research Press

and James Currey Ltd. pp. 3-32. ISBN 0-85255-981-X. OCLC

56194789.

-

Gill, Richardson B. (2000). The

Great Maya Droughts: Water, Life, and Death. Albuquerque:

University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-826-32194-1. OCLC

43567384.

-

Hammond, Norman (2000). "The Maya

Lowlands: Pioneer Farmers to Merchant Princes". in Richard E.W.

Adams and Murdo J. Macleod (eds.). The Cambridge History of the

Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 197-249. ISBN

0-521-35165-0. OCLC 33359444.

-

Harrison, Peter D. (2006). "Maya

Architecture at Tikal". in Nikolai Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine

Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel

(assistant eds.). Köln: Könemann. pp. 218-231. ISBN

3-8331-1957-8. OCLC 71165439.

-

Kelly, Joyce (1996). An

Archaeological Guide to Northern Central America: Belize,

Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Norman: University of

Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2858-5. OCLC 34658843.

-

Kerr, Justin (n.d.). "A Precolumbian

Portfolio" (online database). FAMSI Research Materials.

Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc.

http://research.famsi.org/kerrportfolio.html. Retrieved

2007-06-13.

-

Looper, Matthew G. (1999). "New

Perspectives on the Late Classic Political History of Quirigua,

Guatemala". Ancient Mesoamerica (Cambridge and New York:

Cambridge University Press) 10 (2): 263-280. ISSN 0956-5361.

OCLC 86542758.

-

Looper, Matthew G. (2003). Lightning

Warrior: Maya Art and Kingship at Quirigua. Linda Schele series

in Maya and pre-Columbian studies. Austin: University of Texas

Press. ISBN 0-292-70556-5. OCLC 52208614.

-

Martin, Simon; and Nikolai Grube

(2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the

Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London and New York: Thames &

Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05103-8. OCLC 47358325.

-

Martin, Simon; and Nikolai Grube

(2008). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the

Dynasties of the Ancient Maya (2nd edn (revised) ed.). London

and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28726-2. OCLC

191753193.

-

Martínez, Horacio; David Webster;

Jay Silverstein; Timothy Murtha; Kirk Straight and Irinna

Montepeque (2004). "Reconocimiento en la periferia de Tikal: Los

Terraplenes Norte, Oeste y Este, nuevas exploraciones y

perspectivas" (PDF online publication). XVII Simposio de

Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2003 (edited by J.P.

Laporte, B. Arroyo, H. Escobedo and H. Mejía). Museo Nacional de

Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. pp. 635-641. http://www.asociaciontikal.com/pdf/56.03%20-%20Horacio%20-%20en%20PDF.pdf.

Retrieved 2009-06-24. (Spanish)

-

Miller, Mary Ellen (1999). Maya Art

and Architecture. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN

0-500-20327-X. OCLC 41659173.

-

Miller, Mary; and Karl Taube (1993).

The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An

Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames

& Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

-

Salisbury, David; Mimi Koumenalis,

and Barbara Moffett (19 September 2002). "Newly revealed

hieroglyphs tell story of superpower conflict in the Maya world"

(PDF online publication). Exploration: the online research

journal of Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt

University Office of Science and Research Communications). OCLC

50324967. http://exploration.vanderbilt.edu/print/pdfs/news/news_dospilas_feature.pdf.

Retrieved 2009-09-22.

-

Schele, Linda; and Peter Mathews

(1999). The Code of Kings: The language of seven Maya temples

and tombs. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-85209-6.

OCLC 41423034.

-

Sharer, Robert J.; with Loa P.

Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th, fully revised ed.).

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9.

OCLC 57577446.

-

StarWars.com. "Star Wars: Episode IV

A New Hope". Lucasfilm Ltd. http://www.starwars.com/movies/episode-iv/.

Retrieved 2009-11-13.

Torres, Estuardo. "Parque Nacional Tikal". Ministerio de Cultura

y Deportes. http://www.mcd.gob.gt/2009/04/03/parque-nacional-tikal/.

Retrieved 2009-11-14. (Spanish)

-

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Tikal

National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/64.

Retrieved 2009-11-13.

-

Webster, David L. (2002). The Fall

of the Ancient Maya: Solving the Mystery of the Maya Collapse.

London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05113-5. OCLC 48753878.

Back to Contents

Tikal

del Sitio Web

Wikipedia

Templo II o Templo de las Máscaras

y también denominado Templo de la

Luna.

Tikal es la más grande de las antiguas ciudades de los mayas del

período clásico. Está situada en la región de Petén, en el

territorio actual de Guatemala.

Tikal fue uno de los principales centros culturales y poblacionales

de la civilización maya. La tumba del posible fundador de la

dinastía Yax Ehb' Xook data de ca. año 60, aunque muestra ocupación

desde ca. 600 a. C. según hallazgos en Mundo Perdido, la parte más

antigua de la ciudad.

Prosperó principalmente durante el período clásico maya,

aproximadamente de 200 a 850, después del cual no se construyeron

monumentos mayores, algunos palacios de la élite fueron quemados, y

la población gradualmente decayó hasta que el sitio fue abandonado a

finales del siglo X.

El último monumento fechado data de 899.

Toponimia

El nombre "Tikal" significa "Lugar de las Voces" o "Lugar de las

Lenguas" en maya, y fue acuñado por Sylvanus Morley.

Su verdadero

nombre de acuerdo a los textos jeroglíficos es Mutul o Yax Mutul de

Mut nudo, haciendo referencia al peinado del Ku'hul Ahaw o máximo

Gobernante.

La

Ciudad

Templo 1 o Templo del Gran Jaguar.

Los estudiosos estiman que en su máximo apogeo, tuvo una población

de 100.000 a 150.000 habitantes.

Entre los edificios más prominentes

que sobreviven están seis grandes templos piramidales y el palacio

real, además de algunas pirámides más pequeñas, palacios,

residencias y piedras talladas.

El área residencial de Tikal cubre un estimado de 60 km², de los

cuales sólo 16 km² han sido limpiados o excavados. En la actualidad

existen dudas acerca de la posible demografía que se sitúa en un

amplio abanico de 100.000 a 200.000 habitantes, superando los 49.000

habitantes estimados por Haviland en 1970.

En la Acrópolis Central,

que fue su centro administrativo, y comprende 45 estructuras se

encuentra un Palacio de cinco pisos de altura.

-

El templo principal (o también denominado templo I), que cierra la

plaza por el lado este, es el denominado Templo del Gran Jaguar, con

una altura total de 55 m. Se piensa que fue construido hacia el año

700, y es la tumba de Hasaw Cha'an Kawil, el que devolvió la

supremacía de Tikal sobre las otros centros mayas, al derrotar

sucesivamente a Waka', Caracol y Calakmul.

-

El templo II, denominado Templo de las Máscaras o "Pirámide de La

Luna", con una altura de 50 m, cierra la gran plaza por el lado

oeste y es la tumba de la esposa de Hasaw Cha'an Kawil. La Acrópolis

Norte a la derecha de estos Templos es un conjunto de Pirámides más

pequeñas y que fueron la Tumba de los Primeros Señores de Tikal.

-

El Templo III, o Templo del Gran Sacerdote, fue el último en ser

construido. 810 d.c. por Chi’taam , es el que tiene la crestería más

fina y mejor conservada del Mundo Maya.

-

El Templo IV o Templo de la Serpiente Bicéfala, es el más alto del

sitio con 64 m, fue construido por el hijo de Hasaw Cha'an Kawil,

Yaxk'in Cha'an Chac que tomo el poder el 12 de diciembre de 734,

esta era considerada la construcción más alta de la América

Precolombina, hasta el descubrimiento de la Pirámide de La Danta, en

El Mirador, que con sus 72 m de altura, es el edificio más alto de

la América Precolombina y el de mayor volumen de construcción en el

Mundo Antiguo, con sus 2,800,000 Metros cúbicos.

-

El Templo V ca. 780, es la única pirámide del sitio en la cual no

se ha descubierto una Tumba.

-

El Templo VI o De las Inscripciones, llamado así por el extenso

texto, en su parte trasera, el más largo de un templo Maya, fue

comisionado por Yaxk'in Ca'an Chac ca. 750.

Templo IV o Templo de la Serpiente Bicéfala,

el

mayor de Tikal, visto desde Mundo Perdido.

Como es frecuente el caso con grandes ruinas antiguas, el

conocimiento del sitio nunca se perdió completamente en la región.

Algunos apuntes de segunda o tercera mano aparecen impresos

comenzando en el siglo XVII, y continuando con los escritos de

John

Lloyd Stephens a principios del siglo XIX. Debido a lo remoto que se

encuentra de las ciudades modernas, sin embargo, ninguna expedición

científica visitó Tikal sino hasta 1848. Fue reportada en 1848, por

Modesto Méndez y Ambrosio Tut, corregidor y gobernador de Petén,

respectivamente.

Eusebio Lara acompañó esta primera expedición para elaborar las

primeras ilustraciones de los monumentos. Muchas otras expediciones

llegaron para seguir investigando, dibujando mapas, y fotografiando Tikal en los siglos XIX y XX.

En 1853, posterior a la publicación del diario de Méndez en la

Gaceta de Guatemala, se da a conocer a la comunidad científica el

descubrimiento, en una publicación de la Academia de Ciencias de

Berlín.

Dos

estelas en la Acrópolis Norte.

En 1951 se construyó una pequeña pista de aterrizaje cerca de las

ruinas, que anteriormente sólo podían ser alcanzadas luego de varios

días de viaje a través de la selva a pie o en mula.

De 1956 a 1970

se hicieron importantes excavaciones arqueológicas por parte de la

Universidad de Pensilvania. En 1979 el gobierno guatemalteco inició

un proyecto arqueológico en Tikal, que continúa hasta el día de hoy.

Las ruinas de Tikal, como parte del Parque Nacional Tikal, fueron el

primer sitio arqueológico en ser declarado Patrimonio de la

Humanidad en 1979, y así mismo, el primer Patrimonio de la Humanidad