|

by Eryn Brown from LosAngelesTimes Website

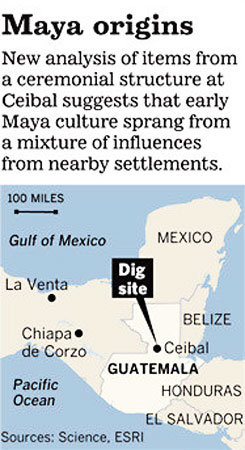

at the Ceibal site in Guatemala suggest that Maya culture grew from

an amalgam of influences.

(Takeshi Inomata /

September 14, 2006)

The classic Maya civilization, which flourished in Central America for more than 600 years, has been celebrated for its vast city states adorned with monumental pyramids and for its technological feats such as the development of an elaborate written language and impressively accurate astronomical observations.

But for decades, archaeologists have argued over the birth of the culture that spawned those splendid cities about 1000 BC. A new analysis of items from a long-buried ceremonial structure in central Guatemala supports a third hypothesis, researchers reported Thursday - that lowland Maya culture grew out of an amalgam of influences from nearby settlements.

In his view, the culture that went on to dominate Mesoamerica until the arrival of Europeans got its start during a power vacuum that lasted for about 200 to 350 years in a period of Olmec rule.

That allowed the people who built the ceremonial structure at a site known as Ceibal to interact with others from nearby areas and begin forming a new culture.

They probably had influences from as far away as Chiapas and the Pacific Coast, both about 200 miles away.

Takeshi Inomata has been working at Ceibal, in the southwestern Maya lowlands, since 2005.

The people who lived there repeatedly built on the same site over hundreds of years, leaving behind layers of civilization that extend 30 feet or more beneath the surface.

Digging deep to gain access to ancient construction, Inomata and his team - which included his wife, Daniela Triadan, also of the University of Arizona - discovered a collection of structures that archaeologists refer to as "E-Group assemblages."

There was a square building on the west, an open plaza and a long platform on the east. By 700 BC, the building was as much as 26 feet tall.

These types of structures are considered precursors of the monumental pyramids that the Maya later built at sites such as Palenque in southern Mexico. Aligned with the sun's path through the sky, such buildings are believed to have been ritual spaces where the community would have gathered to make offerings.

The team discovered many axes made of green stone at the bottom of the Ceibal plaza - tools that would have been "really valuable for these people" and are thought to be offerings, Inomata said.

To figure out the age of these structures, the team ran carbon-dating tests on dozens of samples of wood and human bone remains from the site.

Using sophisticated statistical models to refine the dating of 54 of the wood samples, they determined that the E-Group at Ceibal dated to 1000 BC - about 200 years earlier than most Maya settlements that adopted the E-Group architecture, Inomata said.

The bones dated as even older, but the researchers didn't include them in the calculations because eating fish can skew the results. That makes the Ceibal buildings the earliest known example of the architecture.

And based on the researchers' understanding of the age of the Olmec center at La Venta, which also had E-Groups, they concluded that Ceibal's ceremonial plaza and buildings were constructed first.

But that doesn't mean that Ceibal had to be the origin of the ceremonial architecture, Inomata added.

Sites in Chiapas and on the Pacific Coast have similar architecture, and they arose in the same period, he said.

Washington University anthropologist David Freidel, who was not involved in the research, called the study "a benchmark contribution." But he said the issue of Olmec influence remained unresolved and that archaeologists would continue to present evidence disputing the La Venta dates.

The debate,

Robert Rosenswig, an archaeologist who specializes in Mesoamerica at the University at Albany, State University of New York, said the discovery that 1000 BC was an important time in the development of Ceibal fit well with his research into the reliance on corn as a staple food among people in the region, which occurred about the same time.

Inomata's research was funded by,

|