|

|

by Philip Coppens |

|

Contents

|

Archaeological Trench Warfare at

Glozel

2007

Extracted from Nexus Magazine

Volume 14, Number 5 (August -

September 2007)

from

NexusMagazine Website

|

When artifacts unearthed

at Glozel, France, in the mid-1920s didn't fit the

accepted scholarly explanation of human prehistory

in that region, archaeologists engaged in a bitter

battle that has still not seen a clear winner.

.

About the Author

Philip Coppens is the editor-in-chief of

Conspiracy Times (http://www.conspiracy-times.com).

He has previously contributed eight articles to NEXUS,

the most recent being "State-Sponsored Terror in the

Western World" (see 14/02). Philip is a scheduled

speaker for the forthcoming NEXUS Conference on the

Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia, on 20-21-22

October.

Philip's website is

http://www.philipcoppens.com,

and he can be contacted by email at

info@philipcoppens.com.

|

The excavations near the French village of Glozel, a hamlet located

17 kilometers from the French spa town of Vichy, are among the most

controversial of archaeological endeavors. These excavations lasted

between 1924 and 1938, but the vast majority of finds-more than

3,000 artifacts - were unearthed in the first two years. The

artifacts were variously dated to Neolithic, Iron Age and Mediaeval

times.

What transpired is a textbook case of archaeological feuding

and fraud versus truth.

Glozel 101 -

How to get ahead in archaeology

If one word could be used to describe the Glozel affair, it should

be "controversial". It has been described as the "Dreyfus affair" of

French archaeology, and the Dreyfus equivalent was Emile Fradin, a

seventeen-year-old, who together with his grandfather Claude Fradin

stepped into history on 1 March 1924.

Working in a field known as Duranthon, Emile was holding the handles

of a plough when one of the cows pulling it stuck a foot in a

cavity. Freeing the cow, the Fradins uncovered a cavity containing

human bones and ceramic fragments. So far, this could have been just

any usual archaeological discovery, of which some are made every

week. That soon changed.

It is said that the first to arrive the following day were the

neighbors. They not only found but also took some of the objects.

That same month, Adrienne Picandet, a local teacher, visited the

Fradins' farm and decided to inform the minister of education. On 9

July, Benoit Clement, another teacher, this time from the

neighboring village and representing La Societe d'Emulation du

Bourbonnais, visited the site and later returned with a man called Viple.

Clement and Viple used pickaxes to break

down the remaining walls, which they took away with them. Some weeks

later, Emile Fradin received a letter from Viple, identifying the

site as Gallo-Roman. He added that he felt it to be of little

interest. His advice was to recommence cultivation of the

field-which is what the Fradin family did. And this might perhaps

have been the end of the saga, but not so.

The January 1925 Bulletin de la Societe d'Emulation du

Bourbonnais reported on the findings. It brought the story to

the attention of Antonin Morlet, a Vichy physician and amateur

archaeologist. Morlet visited Clement and was intrigued by the

findings. Morlet was an "amateur specialist" in the Gallo-Roman

period (first to fourth centuries AD) and believed that the objects

from Glozel were older.

He thought that some might even date

from the Magdalenian period (12,000-9500 BC). Both Morlet and

Clément visited the farm and the field on 26 April 1925, and Morlet

offered the Fradins 200 francs per year to be allowed to complete

the excavation. Morlet began his excavations on 24 May, discovering

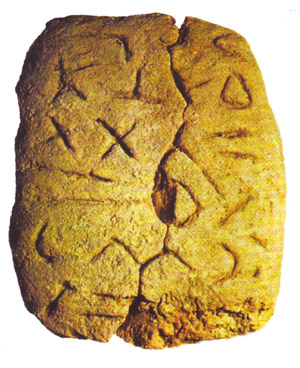

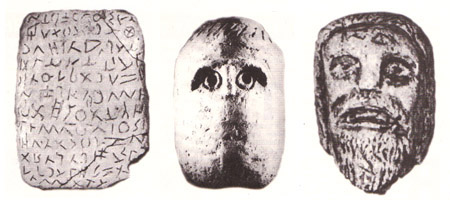

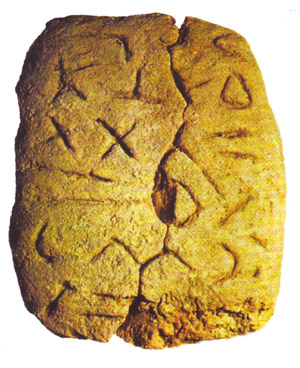

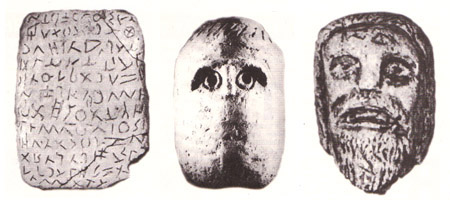

tablets, idols, bone and flint tools, and engraved stones. He

identified the site as Neolithic and published his "Nouvelle Station Néolithique" in September 1925, listing Emile Fradin as co-author.

He argued that the site was, as the title of the article states,

Neolithic in nature.

Though Morlet dated it as Neolithic, he was not blind to see that

the site contained objects from various epochs. He still upheld his

belief that some artifacts appeared to be older, belonging to the

Magdalenian period, but added that the techniques that had been used

appeared to be Neolithic. As such, he identified Glozel as a

transition site between both eras, even though it was known that the

two eras were separated by several millennia.

Certain objects were indeed

anachronistic: one stone showed a reindeer, accompanied by letters

that appeared to be an alphabet. The reindeer vanished from that

region around 10,000 BC, yet the earliest known form of writing was

established around 3300 BC, and that was in the Middle East. The

general consensus was that, locally, one would have to wait a

further three millennia before the introduction of writing. Worse,

the script appeared to be comparable with the Phoenician alphabet,

dated to c. 1000 BC, or to the Iberian script, which was derived

from it. But, of course, it was "known" that no Phoenician colony

could have been located in Glozel.

From a site that seemed to have little or no importance, Glozel

had

become a site that could upset the world of archaeology.

Incontestable

evidence-or not?

No wonder that French archaeological academics were dismissive of Dr

Morlet's report-after all, it was published by an amateur (a medical

doctor) and a peasant boy (who perhaps could not even write

properly). In their opinion, the amateurism dripped off their

conclusion, for it challenged their carefully established and

vociferously defended dogma on several levels. Prehistoric writing?

A crossover between a Palaeolithic and a Neolithic civilization?

Nonsense! And hence, the criticism continued.

One person claimed that the artifacts had to be fakes, as some of

the tablets were discovered at a depth of 10 centimeters. Indeed, if

that were the case they would indeed be fakes, but the problem is

that all the tablets were found at substantial depths-clear evidence

of manipulation of the facts when the facts don't fit the dogma. It

should be noted that the "10 centimeter" argument continues to be

used by several skeptics, who falsely continue to assume it is true.

Unfortunately for French academic

circles, Morlet was not one to lie down easily, and today his ghost

continues to hang-if not watch-over Glozel.

Morlet invited a number of archaeologists to visit the site during

1926; they included Salomon Reinach, curator of the Musée

d'Archéologie Nationale de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, who spent

three days excavating. Reinach confirmed the authenticity of the

site in a communication to the Académie des Inscriptions et

Belles-Lettres. Even higher academic circles descended on the

site: the famous archaeologist Abbé Breuil excavated with Morlet and

was impressed with the site. In late 1926, he wrote two articles, in

which Breuil stated that the authenticity of the Glozel site was

"incontestable".

It seemed too good to be true, and it was.

Breuil worked together with prehistorian André Vayson de Pradenne,

who had visited the site under an assumed name and attempted to buy

the artifacts from Fradin. When Fradin refused, Vayson became angry

and threatened to destroy the site. Under his own name, he obtained

permission to excavate from Dr Morlet, but then claimed to have

detected Fradin spreading salt in the excavation trench. Was Vayson

de Pradenne keeping his promise? Again Morlet chose to attack, and

he challenged Vayson to duplicate what Fradin had allegedly done.

When he was unable to do so, or find where Fradin had supposedly

salted the trench, Morlet felt he had successfully dealt with that

imposter. He was wrong: Vayson de Pradenne's allegation made it into

print.

But it would be a reindeer that soured the relationship between

Breuil and Morlet, as Breuil had identified an engraved animal on a

tablet as a cervid, neither reindeer nor elk.

Morlet had received confirmation from Professor August Brinkmann,

director of the Zoology Department at Bergen Museum, Norway, and

informed Breuil of his mistake. It was the moment when Breuil

changed his attitude. Morlet had begun to make powerful enemies.

More

controversy over site excavations

Rather than talk, Morlet dug, unearthing 3,000 objects over a period

of two years, all of varied forms and shape, including 100 tablets

carrying signs and approximately 15 tablets carrying the imprints of

human hands. Other discoveries included two tombs, sexual idols,

polished stones, dressed stones, ceramics, glass, bones, etc.

Surely, these could not be fakes?

On 2 August 1927, Breuil reiterated that he wanted to stay away from

the site. On 2 October, he wrote that "everything is false except

the stoneware pottery".

Just before that, at the meeting of the International Institute of

Anthropology in Amsterdam held in September 1927, the Glozel site

was the subject of heated controversy. A commission was appointed to

conduct further investigation. Its membership was largely comprised

of people who had already decided the Glozel finds were fraudulent.

Among the group was Dorothy Garrod, who had studied with Breuil.

The commissioners arrived at Glozel on 5 November 1927. During their

excavations, several members found artifacts. But on the third day,

Morlet saw commission members Dorothy Garrod, Abbé Favret and Mr

Hamil-Nandrin slip under the barbed wire and set off towards the

open trench before he had opened the gate. Morlet followed her and

saw that she had stuck one of her fingers into the plaster pattern

on the side of the trench, making a hole. He shouted out,

reprimanding her for what she had just done. Caught in the act, she

at first denied it, but in the presence of her two colleagues as

well as the attorney, Mallat, and a scientific journalist,

Tricot-Royer, she had to admit that she had made the hole.

Though it was agreed they would not speak about the incident

(underlining the fact that some people have more privileges than

others), Morlet did speak about it after the commission had

published its unfavorable report. This might be seen as mudslinging,

trying to get back at the commission, but, unfortunately for those

willing to adhere to this theory, a photograph attested to the

incident. In it, Garrod is hiding behind the four men, who are in

heated discussion about what she had just done. Most importantly,

Tricot-Royer and Mallat also gave written testimony confirming

Morlet's account.

What was Garrod trying to do?

Some have claimed it was merely an

accident, but it is remarkable that she was part of a posse that

entered the site before the "official start" of the day and had an

accident that could have been interpreted as interfering with the

excavation. If others had found that the excavation had been

tampered with, fingers would not have been pointed at Garrod but,

instead, at Fradin - whom the archaeologists suspected of being the

forger, burying artifacts in the ground only to have amateur

archaeologists like Morlet, who did not know "better", discover

them. If this suggestion that Fradin had entered the site at night

had been made, it would have resulted in a "case closed" and the

Glozel artifacts would have been qualified as fraudulent.

The incident did not cause any harm to Dorothy Garrod, who then went

on to teach a generation of British archaeologists at Cambridge.

Perhaps unremarkably, she made sure to tell all of them that the

Glozel artifacts were fakes. And several of her students echoed her

"informed opinion"; the list included Glyn Daniel and

Colin Renfrew,

both fervent critics of the Glozel finds. We can only wonder whether

the "finger incident" is known to these pillars of archaeology.

Remarkably, when challenged with evidence that thermo-luminescence

and carbon dating had shown that the Glozel artifacts could not be

forgeries created by Fradin, Renfrew wrote in 1975:

"The three papers, taken together,

suggest strongly that the pottery and terracotta objects from

Glozel, including the inscribed tablets, should be regarded as

genuine, and with them, presumably, the remainder of the

material... I still find it beyond my powers of imagination to

take Glozel entirely seriously."

Though all the archaeological evidence

suggested the site was genuine, Renfrew's emotions prevented him

from taking it seriously. Whoever said men of science let the facts

rule over emotions?

But back to the past. Morlet sent a letter to Mercure de France

(published on 15 November 1927), still upset with Breuil's

qualification of the site as a fake and having spotted one of his

students sticking an unwanted finger into an archaeological trench:

"From the time your article appeared

I declared to anyone who wanted to listen, especially to your

friends so that you would hear about it, that I would not allow

you to present a site already studied at length as a discovery

which had not been described before you wrote about it. I know

that in a note you quoted the titles of our articles; that you

thank me for having led you to Glozel; and that finally you give

thanks to our 'kindness' in having allowed you to examine our

collections. You acknowledge that I am a good chauffeur.

I have perceived, a little, that I

have also been a dupe. Your report on Glozel is conceived as if

you were the first to study the site so much so that several

foreign scholars are misinformed about it. Your first master, Dr

Capitan, suggested to me forthrightly that we republish our

leaflet with the engravings at the end and his name before mine.

With you, the system has evolved: you take no more than the

ideas."

Morlet was highlighting one of the main

goals of archaeologists: to have their name on top of a report and

be identified as the discoverer. It is standard practice, in which

amateurs specifically are supposed to stand aside and let the

"professionals" deal with it-and take the credit for the discovery.

Again, Morlet did not want to have any

of it.

Peasant boy

versus Louvre curator

The commission's report of December 1927 declared that everything

found at the Glozel site, with the exception of a few pieces of

flint axes and stoneware, was fake. Still, members of the

commission, like Professor Mendes Corrça,

argued that the conclusions were incorrect and misrepresentative. In

fact, he argued that the results of his analyses, when completed,

would be opposite of what had been claimed by Count Bégouen, the

principal author of the report. Bégouen had to confess that he had

made up an alleged dispatch from Mendes Corrça!

René Dussaud, curator at the Louvre and a famous epigrapher, had

written a dissertation that argued that our alphabet is of

Phoenician origin. If Morlet was correct, Dussaud's life's work

would be discredited. Dussaud made sure that would not happen, and

thus he told everyone that Fradin was a forger and even sent an

anonymous letter about Fradin to one of the Parisian newspapers. But

when similar finds to those at Glozel were unearthed in Alvo in

Portugal, Dussaud stated that they, too, had to be fraudulent-even

though the artifacts were discovered beneath a dolmen, leaving

little doubt they were of Neolithic origin.

When similar artifacts were found in the

immediate vicinity of Glozel, at two sites at Chez Guerrier and

Puyravel, Dussaud wrote:

"If, as they claim, the stones

discovered in the Mercier field and in the cave of Puyravel bear

the writing of Glozel, there can be no doubt the engravings on

the stones are false."

What could Fradin do?

In a move that

seems to have been a few decades ahead of his time, on 10 January

1928 Fradin filed suit for defamation against Dussaud. Indeed, a

peasant boy of twenty was suing the curator of the Louvre for

defamation!

Dussaud had no intention of appearing in court and must have

realized that, if he did, he could lose the case. He needed help,

fast, for the first hearing was set for 28 February and Fradin had

already received the free assistance of a lawyer who was greatly

intrigued by a case of "peasant boy versus Louvre curator". Dussaud

engineered the help of the president of the Société

Préhistorique Française, Dr Félix Régnault, who visited

Glozel on 24 February and, after the briefest of visits to the small

museum, filed a complaint against "X".

That the entire incident was engineered is clear, as Régnault had

come with his attorney, Maurice Garçon, who

immediately traveled from Glozel to Moulins to file the complaint.

The accusation was that the admission charge of four francs was

excessive to see objects which in his opinion were fakes. The police

identified "X" as Emile Fradin. The next day, the police searched

the museum, destroyed glass display cases and confiscated three

cases of artifacts.

Emile was beaten when he protested

against the taking of his little brother's schoolbooks as evidence.

Saucepans filled with dirt by his little brother were assumed to be

artifacts in the making. Despite all of this, the raid produced no

evidence of forgery. However, the suit for defamation could not

proceed because a criminal investigation was underway. It meant that

the defamation hearing set for 28 February would not happen for as

long as the criminal investigation continued.

Dussaud, it seemed, had won. Meanwhile, a new group of neutral

archaeologists, the Committee of Studies, was appointed by scholars

who, since the November conference in Amsterdam and specifically

since the report's publication in December, were uncomfortable with

how the archaeological world was handling Glozel. They excavated

from 12 to 14 April 1928 and continued to find more artifacts.

Their report spoke out for the

authenticity of the site, which they identified as Neolithic. It

seemed that Morlet had been vindicated.

Police distort

truth, but Fradin is vindicated

Any vindication was soon outdone when Gaston-Edmond Bayle, chief of

the Criminal Records Office in Paris, analyzed the artifacts seized

in the raid and in May 1929 identified them as recent forgeries.

Originally, Bayle had said that it would take only eight or nine

days to prepare a report, but a year passed without anything being

set down on paper. This, of course, was excellent news for Dussaud,

as it delayed his defamation hearing.

To pave the way, on 5 October 1928

information was leaked to the papers, which played their part by

faithfully stating that the report would conclude that the Glozel

artifacts are forgeries. In May 1929, Bayle completed a 500-page

report, just in time to postpone once again the Dussaud case, which

was scheduled for hearing on 5 June.

Bayle argued that he could detect fragments of what might have been

grass and an apple stem in some of the Glozel clay tablets. As grass

obviously could not have been preserved for thousands of years, it

was obviously a recent forgery, he reasoned. The argument is very

unconvincing, for the excavations were obviously not handled as a

forensic crime scene would be treated. Most likely, the vast

majority of these artifacts were placed on grass or elsewhere after

they were dug up from the pit-a practice that continues on most of

today's archaeological excavations; archaeology, at this level, is

not a forensic science. Later, it would emerge that some of the

objects had also been placed in an oven to dry them-which in due

course would interfere with carbon-dating efforts on the artifacts.

Bizarrely, in September 1930, Bayle was assassinated in an unrelated

event; his assassin accused him of having made a fraudulent report

that had placed him in jail! After his death, it was found that

Bayle had lived an extravagant lifestyle that was inconsistent with

his salary.

Most interestingly, Bayle was close to Vayson de Pradennes, who was

the son-in-law of his former superior at the Criminal Records

Office.

And it seems the Breuil-Vayson de Pradennes-Dussaud axis was not

only powerful in archaeological circles: it could also dictate to

the wheels of the law.

The court accepted Bayle's findings, and on 4 June 1929 Fradin was

formally indicted for fraud. For the next few months, Fradin was

interrogated every week in Moulins. Eventually, the verdict was

overturned by an appeal court in April 1931.

For three years, Dussaud had been able to terrorize Fradin for his

"insolence" in filing a suit against him. Unfortunately, though the

wheels of the law had largely played to the advantage of the "axis

of archaeology", in the final analysis righteousness had won. The

defamation charge against Dussaud came to trial in March 1932, and

Dussaud was found guilty of defamation, with all costs of the trial

to be paid by him.

Eight years after the first discovery, the leading archaeologists

continued to claim the Glozel artifacts were fraudulent, though all

the evidence-including a lengthy legal cause-had shown that was

absolutely not the case. But why bother with facts when there are

pet theories and reputations to be defended?

Morlet ended his excavations in 1938, and after 1942 a new law

outlawed private excavations. The Glozel site remained untouched

until the Ministry of Culture re-opened excavations in 1983. A full

report was never published, but a 13-page summary did appear in

1995.

This "official report" infuriated many, for the authors suggested

that the site was mediaeval, possibly containing some Iron Age

objects, but was likely to have been enriched by forgeries. It

therefore reinforced the earlier position of the leading French

archaeologists. But on 16 June 1990, Emile Fradin received the

Ordre

des Palmes Acadamiques, suggesting that the French academic circles

had accepted him for making a legitimate discovery - and that he was

not a forger. The Glozel excavation site, however, continues to be

seen as a giant hoax.

Emile Fradin was honored that the British Museum requested some of

his artifacts to go on display in 1990 in the "holy of holies" of

archaeology. What he did not know (because of a language barrier)

was that the exhibit was highlighting some of the greatest

archaeological hoaxes and forgeries in history...

Back to Contents

Glozel

The Fraud or Find of the 20th

Century?

from

PhilipCoppens Website

|

From 1924 to 1938, a total

of some 3,000 artifacts, variously dated to Neolithic,

Iron Age and Medieval times were unearthed from Glozel,

a hamlet some 17 km from the French spa town of Vichy.

For some, it is one of the greatest archaeological

discoveries ever; for others, it is one of the most

notorious hoaxes.

Philip Coppens |

If one word should be used to describe Glozel, it should be

“controversial”. Émile Fradin, a young man of 17 years old,

together with his grandfather Claude Fradin stepped into history on

March 1, 1924. They were working in a field known as “Duranthon”,

which has since been renamed as “le Champ des Morts”, or “the Field

of the Dead”. Émile was holding the handles of a plough when one of

the cows pulling it stuck her foot in a cavity.

Freeing the cow, the Fradins uncovered

an underground structure with walls of clay bricks and 16 clay floor

tiles, containing human bones and ceramic fragments. So far, this

could have been just any usual archaeological discovery, of which

some are made every week.

But that soon changed…

It is said that the neighbors began to

arrive the following day and not only found, but also took some of

the objects they found with them. Adrienne Picandet, a local

teacher, visited the Fradin's farm that same month and decided to

inform the Minister of Education. On July 9, Benoit Clément, another

teacher, this time from the neighboring village and representing the

Societé d'Emulation du Bourbonnais, visited the site and

later returned with a man called Viple.

Clément and Viple used pickaxes to break

down the remaining walls, which they took away with them. Some weeks

later, Émile Fradin received a letter from Viple identifying the

site as Gallo-Roman. He added that he felt it to be of little

interest and advised to recommence the cultivation of the field –

which is what the Fradin family did.

A not too ominous start therefore. The January 1925 issue of the

Bulletin de la Societé d'Emulation du Bourbonnais reported on

the findings, specifically focusing on a stone that carried

inscriptions. Despite having stated that the site was of little

interest, Clément requested 50 francs from the organization so that

more organized excavations could occur, but the bulletin reported

that this request had been denied.

The report brought the story to the attention of Antonin Morlet, a

Vichy physician and amateur archaeologist. Morlet visited Clément

and was intrigued by the findings. Morlet was an “amateur

specialist” in the Gallo-Roman period and believed that the objects

from Glozel were older. He believed that some might even date from

the Magdalenian period (12,000-9500 BC), as they involved bone

harpoons and depictions of reindeer, though to be extinct since

10,000 BC.

Both men visited the farm and the field on April 26, 1925, Morlet

offering the Fradins 200 francs per year to be allowed to complete

the excavation. He began his excavations on May 24, discovering

tablets, idols, bone and flint tools and engraved stones. He

published his “Nouvelle Station Néolithique” in September 1925,

listing Émile Fradin as co-author, arguing that the site was, as the

title of the report states, Neolithic in nature.

The book came to the attention of the

media and the first newspaper articles on the site featured in Le

Matin in October and in Le Mercure de France in December.

Though Morlet dated it as Neolithic, he

was not blind to see that the site contained objects from various

epochs. He still upheld his belief that some artifacts appeared to

be older, belonging to the Magdalenian period, but added that the

techniques that had been used appeared to be Neolithic. As such, he

identified Glozel as a transition site between both eras, even

though it was known that the two eras were separated by several

millennia.

Certain objects were indeed anachronistic: one stone showed a

reindeer, accompanied by letters that appeared to be an alphabet. As

mentioned, reindeer were believed to have vanished from the region

around 10,000 BC, yet the earliest known form of writing was then

established at 3300 BC, and that was in the Middle East. The general

consensus was that locally, one would have to wait a further three

millennia before the introduction of writing. Worse, the script

appeared to be comparable with the Phoenician alphabet, dated to ca.

1000 BC, or to the Iberian script, which was derived from it. But –

of course – it was “known” that no Phoenician colony could have been

located in Glozel.

No wonder therefore that French archaeological academia were

dismissive of Morlet's report; after all, it was published by an

amateur – a doctor – and a peasant boy – who could perhaps not even

write properly? The amateurism dripped off their conclusion, for it

challenged their carefully established and vociferously defended

dogma on several levels: prehistoric writing? A cross-over between a

Palaeolithic and Neolithic civilisation? Nonsense!

Unfortunately for French academic circles, Morlet was not one to lay

down easily and today, his ghost continues to watch – if not hang –

over Glozel. Morlet invited a number of archaeologists to visit the

site during 1926, including Salomon Reinach, curator of the National

Museum of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, who spent three days excavating.

Reinach confirmed the authenticity of the site in a communication to

the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres. But even higher

academic circles descended on the site: the famous archaeologist

Abbé Breuil excavated with Morlet and was impressed with the site,

but on October 2 Breuil wrote that "everything is false except the

stoneware pottery" – doing a remarkable turn-around.

What had happened? Breuil worked

together with André Vayson de Pradenne and the latter argued that he

had found, in a popular magazine, images of prehistoric engravings

that were similar to those discovered by Fradin. This led him to

conclude that Fradin had created artefacts conform to the images in

the magazine.

Despite such allegations, Morlet unearthed thousands of objects over

a period of two years, all of varied forms and shape, including a

hundred tablets carrying signs and approximately fifteen tablets

carrying the imprints of human hands. Other discoveries were sexual

idols, polished stones, dressed stones, ceramics, glass, bones, etc.

How Fradin could possibly have made thousands of objects, the likes

of Vayson de Pradenne never explained…

Furthermore, two other tombs were uncovered in June 1927. One

contained 67, the other 121 objects and human remains. It seemed

that Glozel was soon to be accepted as a major archaeological

discovery. At the meeting of the International Institute of

Anthropology in Amsterdam, held in September 1927, Glozel was

therefore the subject of heated debate.

A commission was appointed to do further

investigations and arrived in Glozel on November 5, 1927.

During their three day excavation, the

archaeologists uncovered various artifacts, but in their report of

December 1927, the commission declared everything, with the

exception of a few pieces of flint axes and stone ware, as fake. It

was then that the worst of all accusations was leveled against

Fradin and it came from the highest circle of academia: René Dussaud,

curator at the Louvre and a famous epigrapher, accused Émile Fradin

of forgery.

In a move that seems to have been a few

decades ahead of his time, on January 10, 1927, Fradin then filed

suit for defamation against Dussaud.

That move delineated the two camps: on the one hand, Fradin and

Morlet; on the other side, the academia, led by Dussaud… and any

academic who felt he had, should or better should stand next to this

juggernaut. No surprise therefore to see the president of the French

Prehistoric Society Felix Regnault visit Glozel on February 24, and

after the briefest of visits to the small museum, filing a complaint

against X –i.e. Fradin.

The accusation was that the cost of 4

francs of admission charges was excessive to see objects which in

his opinion were fake. The police searched the museum the next day,

destroyed glass display cases and confiscated three cases of

artifacts. On February 28, the suit against Dussaud was postponed

due to Regnault's pending indictment against Fradin – the criminal

case of fraud taking priority over the civil action suit.

A new group of neutral archaeologists, called the Committee of

Studies, was appointed by scholars who were uncomfortable with the

legal indictment slinging between the two camps as well as the

Commission that had been set up during the Amsterdam conference.

They excavated from 12 to 14 April 1928 and also found artifacts.

Their report spoke out for the authenticity of the site, which they

identified as Neolithic. It seemed that Morlet had been vindicated,

but the conclusion was soon shrunk in importance when Gaston-Edmond

Bayle, chief of the Criminal Records Office in Paris analyzed the

confiscated artifacts and in May 1929 identified them as recent

forgeries.

Bayle argued that he could detect fragments of what might have been

grass and an apple stem in some of the Glozellian clay tablets. As

grass obviously could not have withstood thousands of years, it was

a recent forgery. The argument is very unconvincing, for the

excavations were obviously not done as a forensic crime scene would

be treated. Most likely, the vast majority of these artifacts were

placed on grass or elsewhere after they were dug up from the pit – a

practice that continues on most of today’s archaeological

excavations; archaeology is, at this level, not a forensic science.

Furthermore, it is known that some of

the objects were actually heated in the oven of Fradin’s home, to

dry them. Bizarrely, a few months later, Bayle was assassinated in

an unrelated event; his assassin accused him of having made a

fraudulent report against him! Still, his subordinates continued his

work and they too were critical of the site, as was a report on the

artifacts produced by Champion, a technician at the Museé de St.

Germain-en-Laye.

As a consequence of Bayle’s report, on June 4, 1929, Émile Fradin

was indicted for fraud, but the judge eventually dismissed the case

in April 1931. This meant that the defamation charge against Dussaud

could and did come to trial in March 1932; Dussaud was found guilty

of defamation. Everyone will agree that all of this had very little

to do with archaeology and a lot to do with ego.

Morlet excavated the site from 1925 to

June 1938. During this decade of research, he discovered tables,

figurines, silex and bone utensils, engraved stones, etc. During the

1950s, Dr. Morlet made two attempts to have Glozel bones dated by

the new carbon-dating technique, once in France and once in the

United States. He died in 1965 without achieving the authentication

for which he had fought so hard.

The last time Fradin saw Morlet, the

doctor told him:

"You mustn't give up, you know. The

truth will come out before long."

So: fraud or genuine?

Perhaps the best

evidence that the site is genuine is Emile Fradin himself: a boy of

17 years of age, not very well educated, who would have spent

thousands of man-hours to create something he never sold? It seems

unlikely. Indeed, Fradin always refused to sell his objects.

Furthermore, all the experts in the field of prehistory initially

recognized the site as authentic; it were non-scientific

considerations that persuaded Capitan and to some extent Breuil to

switch sides: Morlet refused to name either as co-authors in his

report, whereas Vayson de Pradenne was upset because Fradin refused

to sell him his collection.

As to Dussaud, the man who rallied the

troops around him: he too had an ulterior motive, for in a recent

article, he had proposed that our alphabet was a Phoenician

invention. Morlet on the other hand argued that writing was known in

Europe millennia before. If Morlet and Glozel were right and

genuine, Dussaud’s theory would have been discredited. In

retrospect, neither his academic theories nor his character are

fondly remembered.

After 1942, a new law outlawed private excavations and the site

remained untouched until the Ministry of Culture re-opened

excavations in 1983. A full report was never published, but a 13

page summary appeared in 1995. This “official report” infuriated

many, for the authors suggested that the site was medieval, possibly

containing some Iron Age objects, but was likely enriched by

forgeries. It therefore reinforced the earlier position of the

leading French archaeologists. But on June 16, 1990, Emile Fradin

received the “Palmes Académiques”, suggesting that the French

academic circles had accepted him as making a legitimate discovery –

and that he was not a forger.

As late as 1990, Glozel thus continued to be controversial and not

at all straightforward. The official report states that glass found

at Glozel shows it is indeed from the medieval period. Furthermore,

in 1995, Alice and Sam Gerard, together with Robert Liris, dated two

bone tubes found in Tomb II to the 13th century. So there is a

medieval dimension to Glozel. If medieval, it would not be the

spectacular discovery that many have given it, but it would also

confirm that Fradin did not create the site. But that is not the

total “truth”.

Thermo-luminescence dating of 27

artifacts revealed three distinct periods: the first between 300 BC

and 300 AD (Celtic and Roman Gaul, as the earliest report on Glozel

had indicated), the second medieval (13th century), and the third,

rather remarkably, recent, suggesting these could potentially be

frauds mixed with genuine artifacts. And though carbon-dating of

bone fragments have ranged from the 13th to the 20th century, one

human femur was actually dated to the 5th century.

So, it seems, Morlet was wrong and Glozel was not a Neolithic site.

What was it then?

The central “Fosse Ovale” is now known to have

been a glass kiln which was then converted, in the 13th century,

into a tomb. Tomb I and II seem to have been Gallo-Roman tombs,

though a skull found in Tomb I was dated to the 19th century and

three human skulls from Tomb II to the 13-14th century. The “hard”

evidence therefore suggests that there is no Neolithic dimension to

the site and that it is at best Gallo-Roman, to which burials were

added in the 13th century.

Morlet had been convinced of its Neolithic origins because of the

artifacts uncovered at the site. The depiction of reindeer had

pushed it to 10,000 BC, though it is now known that reindeer

survived in isolated locations in Europe and may have been known as

late as Gallo-Roman if not medieval times. Whereas some have argued

the depictions of reindeer are actually red deer, qualified

zoologists (rather than archaeologists) have identified the

engravings as reindeer, not red deer as the archaeologists prefer to

label them.

By far the most captivating, and

controversial aspect of the site are the so-called “Glozel tablets”.

Some 100 ceramic tablets bearing inscriptions have been found. The

inscriptions are on average on six or seven lines, mostly on a

single side, although some specimens are inscribed on both faces. If

these had been Neolithic, Glozel would have been evidence that our

Neolithic ancestors had a script and would have caused a scientific

reappraisal of our forefather’s knowledge.

Are they?

The tablet inscriptions are reminiscent

of the Phoenician alphabet and for some are precisely that. Over the

years, there have been numerous claims of decipherment, including

identification of the language of the inscriptions as Basque, Chaldean, Eteocretan, Hebrew, Iberian, Latin, Berber, Ligurian,

Turkic and the already mentioned Phoenician.

Amongst the various

attempts, one stands out: the suggestion from Hans-Rudolf Hitz, who

suggested a Celtic origin for the script and dated the inscriptions

to between the 3rd century BC and the 1st century AD – a timeframe

that would be acceptable by academics, as it sits within the three

periods identified via thermo-luminescence and carbon-dating, and

which conforms to Clément’s conclusion.

Hitz created an alphabet of 25 signs,

augmented by some sixty variations and ligatures and believed that

it was influenced by the Lepontic alphabet of Lugano, itself

descended from the Etruscan alphabet, reading some Lepontic proper

names like Setu (Lepontic Setu-pokios), Attec (Lepontic Ati, Atecua),

Uenit (Lepontic Uenia), Tepu (Lepontic Atepu). Hitz even claims

discovery of the toponym Glozel itself, as nemu chlausei "in the

sacred place of Glozel" (comparing nemu to Gaulish nemeton).

Still, Hitz also argues that there are

some inscriptions that do not make any sense whatsoever and these

nonsensical artifacts have been dated by other means to the 13th

century; it is believed that those who used the site as a cemetery

in the 13th century tried to copy some of the older artifacts found

on site, but as they were obviously unable to understand the script,

tried to imitate the signs seen on the stones and urns, ending up

with nonsense, but a nevertheless aesthetically pleasing offering

for their deceased.

Though Fradin continues to believe Morlet and the site’s Neolithic

nature, few now support it, seeing that the “hard dating” techniques

have provided far more recent dates. Furthermore, Glozel is not as

important as its notoriety has made it appear. It has been described

as the “Dreyfus Affair” of French archaeology. In early 1999, Guy

Lesec described Glozel as a Rorschach test.

Despite all of that, the possibility of a Neolithic dimension was

reopened in 1993, when a megalithic alignment made up out of 111

stones between the field and Glozel was discovered. The alignment

sits along an old road and leads up to the brow of the hill, where

there is a half circle with a large boulder in the centre. The

megalithic alignment was partially destroyed in the early 20th

century, but it is known to have been about 100 meters long and

roughly orientated north-south, in the direction of Field of Death.

This is evidence that Glozel as a whole had a Neolithic component.

Finally, Glozel is not as unique as many believe. After the initial

discovery had been made, Claude Fradin remembered that the Guillonet

family, the tenant farmers who lived there before them, had found a

vase with a mysterious inscription around it in the same field. In

January 1928, the Mercier family, who owned Chez Guerrier, the farm

next to Glozel, found a stone inscribed with 21 letters and a horse.

He got in touch with Morlet, who found

more artifacts on the site. Other sites in area added to the

treasure chest. The site of Puyravel, 2.5 km from Glozel, yielded 13

stone artifacts, some engraved with animals and letters. Artifacts

were also found at Palissard, 500 meters from Glozel, and Moulin-Piat,

2.5 km from the site. It suggests that the entire area was of some

importance to our forefathers, where vases and other materials were

either buried together with dead, or where these artifacts were

offered, perhaps because the area was sacred to a specific deity.

But the shadow of Glozel’s controversy

is so strong and controversial that the true history of the region

may never be illuminated… and our understanding of history is the

biggest victim in an affaire that should since long have progressed

from the fake-no fake debate.

Back to Contents

|