|

by

Maria-José Viñas

NASA's Earth Science News Team

Editor: Rob Garner

October 30, 2015

from

NASA Website

Recovered through

WayBackMachine Website

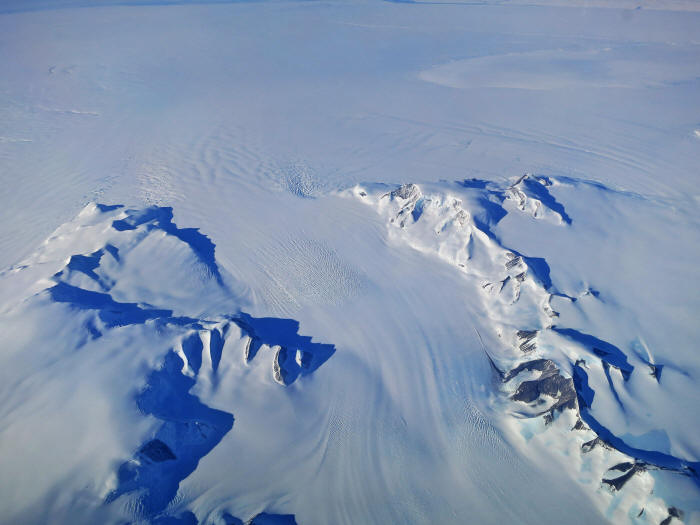

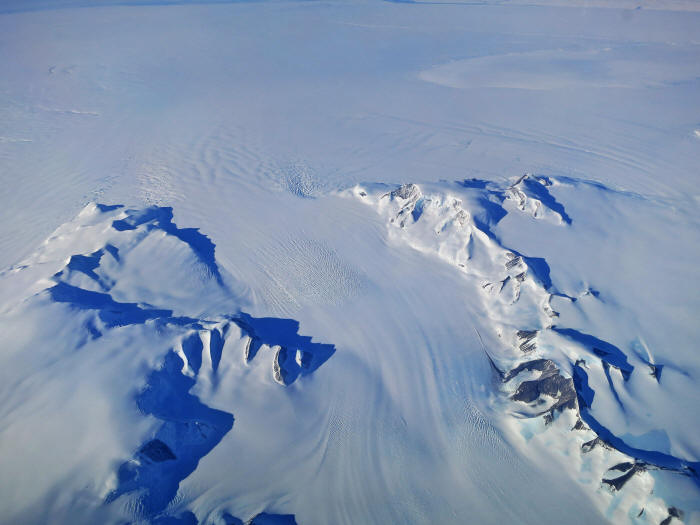

A new NASA study

says that

Antarctica is overall accumulating ice.

Still, areas of

the continent, like the

Antarctic

Peninsula photographed above,

have increased

their mass loss in the last decades.

Credits: NASA's Operation IceBridge

A new NASA study (Mass

Gains of the Antarctic Ice Sheet exceed Losses) says that

an increase

in Antarctic snow accumulation that

began 10,000 years ago is currently adding enough ice to the

continent to outweigh the increased losses from its thinning

glaciers.

The research challenges the conclusions of other studies, including

the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC)

2013 report, which says that,

Antarctica is overall "losing" land ice...

According to the new analysis of satellite data,

the Antarctic ice sheet showed a net gain of 112 billion

tons of ice a year from 1992 to 2001.

That net gain slowed to 82 billion tons of ice

per year between 2003 and 2008.

"We're essentially in agreement with other

studies that show an increase in ice discharge in the Antarctic

Peninsula and the Thwaites and Pine Island region of West

Antarctica," said

Jay Zwally, a glaciologist

with NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland,

and lead author of the study, which was published on Oct. 30 in

the Journal of Glaciology.

"Our main disagreement is for East

Antarctica and the interior of West Antarctica

- there, we see an ice gain that exceeds the losses in the other

areas."

Zwally added that his team,

"measured small height changes over large

areas, as well as the large changes observed over smaller

areas."

Scientists calculate how much the ice sheet is

growing or shrinking from the changes in surface height that are

measured by the satellite altimeters.

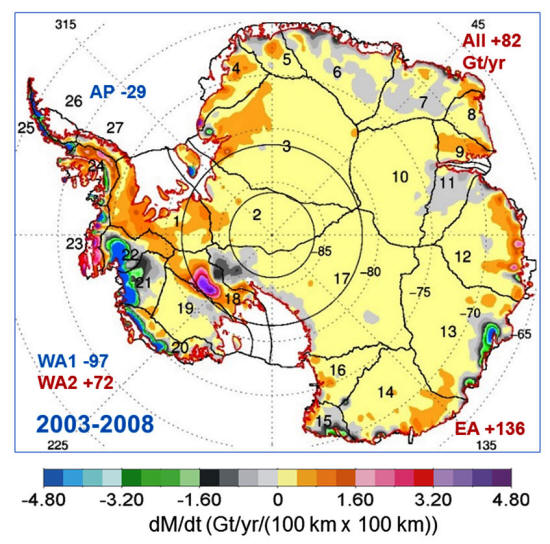

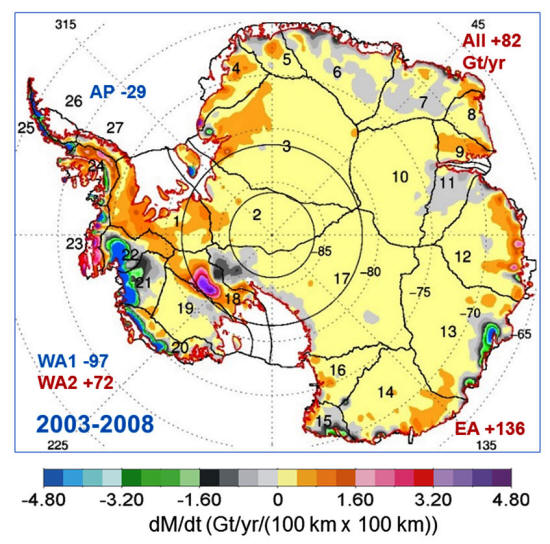

Map showing the rates of

mass changes

from ICESat 2003-2008 over Antarctica.

Sums are for

all of Antarctica: East Antarctica (EA, 2-17);

interior West

Antarctica (WA2, 1, 18, 19, and 23);

coastal West

Antarctica (WA1, 20-21);

and the

Antarctic Peninsula (24-27).

A gigaton (Gt)

corresponds to

a billion

metric tons, or 1.1 billion U.S. tons.

Credits: Jay Zwally/ Journal of Glaciology

In locations where the amount of new snowfall

accumulating on an ice sheet is not equal to the ice flow downward

and outward to the ocean, the surface height changes and the

ice-sheet mass grows or shrinks.

But it might only take a few decades for Antarctica's growth

to reverse, according to Zwally.

"If the losses of the Antarctic Peninsula and

parts of West Antarctica continue to increase at the same rate

they've been increasing for the last two decades, the losses

will catch up with the long-term gain in East Antarctica in 20

or 30 years...

I don't think there will be enough snowfall

increase to offset these losses."

The study analyzed changes in the surface height

of the Antarctic ice sheet measured by radar altimeters on two

European Space Agency European Remote Sensing (ERS)

satellites, spanning from 1992 to 2001, and by the laser altimeter

on NASA's Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat)

from 2003 to 2008.

Zwally said that while other scientists have assumed that the

gains in elevation seen in East Antarctica are due to recent

increases in snow accumulation, his team used meteorological data

beginning in 1979 to show that the snowfall in East Antarctica

actually decreased by 11 billion tons per year during both the ERS

and ICESat periods.

They also used information on snow accumulation

for tens of thousands of years, derived by other scientists from ice

cores, to conclude that

East Antarctica has been

thickening for a very long time...

"At the end of the last

Ice Age, the air became warmer

and carried more moisture across the continent, doubling the

amount of snow dropped on the ice sheet," Zwally said.

The extra snowfall that began 10,000 years ago

has been slowly accumulating on the ice sheet and compacting into

solid ice over millennia, thickening the ice in East

Antarctica and the interior of

West Antarctica by an average of

0.7 inches (1.7 centimeters) per year.

This small thickening, sustained over thousands

of years and spread over the vast expanse of these sectors of

Antarctica, corresponds to a very large gain of ice - enough to

outweigh the losses from fast-flowing glaciers in other parts of the

continent and reduce global sea level rise.

Zwally's team calculated that the mass gain from the thickening of

East Antarctica remained steady from 1992 to 2008 at 200 billion

tons per year, while the ice losses from the coastal regions of West

Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula increased by 65 billion tons

per year.

"The good news is that Antarctica is

not currently contributing to sea level rise, but is

taking 0.23 millimeters per year away," Zwally said.

"But this is also bad news. If the 0.27

millimeters per year of sea level rise attributed to Antarctica

in the IPCC report is not really coming from Antarctica, there

must be some other contribution to sea level rise that is not

accounted for."

"The new study highlights the difficulties of measuring the

small changes in ice height happening in East Antarctica," said

Ben Smith, a glaciologist with the University of

Washington in Seattle who was not involved in Zwally's study.

"Doing altimetry accurately for very large areas is

extraordinarily difficult, and there are measurements of snow

accumulation that need to be done independently to understand

what's happening in these places," Smith said.

To help accurately measure changes in Antarctica,

NASA is developing the successor to the ICESat mission,

ICESat-2, which is scheduled to

launch in 2018.

"ICESat-2 will measure changes in the ice

sheet within the thickness of a No. 2 pencil," said Tom

Neumann, a glaciologist at Goddard and deputy project

scientist for ICESat-2.

"It will contribute to solving the problem of

Antarctica's mass balance by providing a long-term record of

elevation changes."

Related Link

|