|

June 2002

Indeed, the popular consensus

that

Nibiru, a mythological planet as yet unaccounted for by scientists, is

about to appear in our skies, may be intrinsically wrapped up with our

common dread of cataclysm. In the same way that many incorrectly anticipated

an apocalyptic event prior to the turn of the Millennium, advocates of the

2003 hypothesis believe that we are about to face our gravest test since the

Flood.

Yet, there is some merit to the idea that Planet X may be

associated with catastrophe. In this paper I will outline a new hypothesis

that seeks to configure the orbital behavior of this hidden dark star with

catastrophic events as recorded by geologists and paleontologists.

I am often confronted with e-mails that state that Planet X could not have appeared in our skies on such-and-such a date because there was no massive catastrophe associated with its arrival.

The implication is

that every time the Dark Star were to enter the planetary zone, the Earth

(and presumably some other planets too) would be subject to fundamental

change. So if the Dark Star exhibits an orbit analogous with Sitchin’s 3600

years, the implication is that Nibiru causes devastation on a highly regular

basis… extremely often when viewed on a geological scale. I don’t accept

this: it does not fit with the evidence at our disposal.

But we now understand that many cataclysms have occurred, and that evolution is a more ‘stop-go’ affair than one of slow, incremental change. We know that continents drift across the face of the Earth, bringing about the creation of mountain ranges as land-masses lock horns. Further, we know that significant extinction events have blighted our planet, even worse than the heinous acts of mass extinction we are currently responsible for.

Our awareness has been raised about how fragile our world can be, and also how changeable when seen through the eyes of a geologist. We have moved from a theological world-view that led us to believe that the world was created to meet our needs, to a more terrifying reality. We live in a world whose stability is not guaranteed.

Our environment has changed many times in the past, sometimes orders of magnitude worse than the global warming we have created through our industrial negligence.

This reflects the sheer scale of the solar system, and the almost

negligible proportion of it that is actually occupied by planets, asteroids

and comets. The planetary solar system consists mostly of open, empty space.

Even if two objects orbiting the Sun have paths that cross each other, the

possibility of a collision is extremely remote.

As the size of the object decreases, its relative danger threshold would quickly fall away. Large brown dwarfs passing through the planetary zone might pose a problem. Small brown dwarfs probably wouldn’t. (The threshold appears to be 10 Jupiter masses).

Regular size planets, or even gas giants, passing through the solar

system would no more cause a problem to us than an alignment of the known

planets.

Only when its mass

exceeds Jupiter could it begin to become a real player in the catastrophe

stakes.

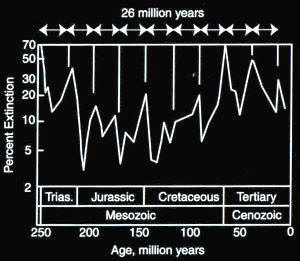

The pattern implied a 26 million year cycle, itself indicative of an extra-terrestrial cause. There are no known terrestrial causes for such massive and regular extinctions.

Could Planet X be to blame, perhaps through

showering Earth with comets as it achieves perihelion?

So it would not be

satisfactory, then, to associate a 26 million-year extinction cycle with a

planet whose orbit is measured in thousands of years only. Nibiru’s

relatively short orbit (Zecharia Sitchin’s ‘Sar’ of 3600 years) could only

produce a random pattern of extinction events on this time-scale.

This theoretical body was called ‘Nemesis’. Its orbital

period at such a great distance (about 90,000AU!) would then be analogous

with the 26 million-year extinction pattern. Somehow, the argument went,

Nemesis would bombard the planetary zone with a massive shower of comets at

a given point of its orbital cycle, without ever approaching the planetary

zone itself.

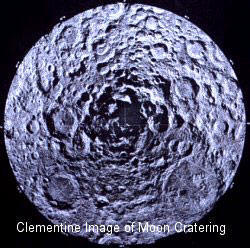

The black dwarf would have had to have literally peppered the Sun with comets every 26 million years, like a Chicago mob catching up with one of their old buddies. In which case there would have to be ample evidence of renewed and regular cratering of other planets in the solar system too. But instead the solar system cratering patterns show little activity in recent epochs, implying a different mechanism for the ‘cyclic’ extinction patterns.

Lone

killer asteroids perhaps, but not massive comet swarms. One or two of these

catastrophes (like the K/T boundary devastation) may have been caused by an

asteroid strike, but the alleged 26 million-year extinction cycle cannot be

accounted for by a routine act of cosmic pummeling.

Advocates of the Nemesis theory might argue that there is an interaction with the galactic tide, or an association with the Sun’s 30 million year motion through the galactic plane, that triggers such a catastrophic release of comets. But this seems unlikely to me. One might as well simply look to the motion of the Sun around the galactic centre, and miss out the middle-man (or middle-dwarf, in this case).

The bottom line is that a cosmic Nemesis is simply too distant,

and irrelevant, to periodically facilitate such devastating killing events.

In my book ‘Winged Disc’ I proposed a possible explanation for how a brown dwarf could on the one hand create a non-random pattern of comets from the distant Oort Cloud, and on the other actually appear in the solar system. That explanation hinged on the possibility that the dark star’s loosely-bound orbit around the Sun was subject to change in a manner not often considered by astronomers.

Astronomers are used to thinking about planets behaving themselves, and only small bodies like comets becoming perturbed from their restful canter around the Sun.

But why couldn’t a planet among the comets also behave like a

comet?

Such events are known as 'oscultations'. The subsequent passage of an Oort Cloud intruder past, or through, the planetary zone could trigger another orbital change, this time into a Sitchin-like elliptical orbit. (Those occasions would be rare, of course, but then so are mass extinctions...)

Although passing stars would likely sail on past (given their considerable size and momentum), the dwarfs run a very real chance of becoming captured by the Sun. Indeed, his calculations showed that a subsequent temporary orbit of the captured dwarf could be highly eccentric, possibly degrading over time.

This is in contrast to the general flat

assumption that such a body would quickly be expelled from the solar

system...

But there would be a different effect, one that is generally appreciated by astrophysicists, but not well disseminated. There is an energetic relationship between the orbits of the Sun’s children. The ‘planetary binding energies’ are not fixed, but intertwined. Introduce a new, maverick element to the solar system (particularly one of considerable mass) and those binding energies are subject to change, even if the planets are tightly bound in stable, circular orbits.

Hills indicated that the overall energy of the orbits of the known

planets could alter if the interloper’s own orbit around the Sun changed.

This might happen if the interloper came from interstellar space and was

captured by the Sun, or if it was an Oort Cloud object that had trespassed

into the planetary zone and taken on a new, more tightly bound temporary

orbit.

Simply put, the solar system would be

subject to possible contraction or expansion, dependent upon the particular

event. The very distances of the planets from the Sun would be subject to

change! The dwarf would not need to directly interact with the planets,

either…simply the changing relationship with the Sun would be enough to

affect other bodies in the solar system.

But below 20 Jupiter masses, an interloper would not create the same devastation. In other words, a small brown dwarf might just have been captured by the Sun in the remote past, and the solar system would still appear as stable as it is thought to be today.

So, if Planet X is a small brown dwarf, then physical mechanisms have been studied scientifically that do actually allow for its existence. Furthermore, those calculations show that the interaction between this dwarf and the rest of the solar system might have fundamental physical ramifications. The distance between the Earth and the Sun might have been altered.

I have chosen three examples of sustained catastrophic damage to our world to illustrate how this hypothesis might work.

They start with the most

recent, and work backwards to the early solar system.

The scale of the destruction of life on Earth was an order of magnitude greater than the wiping out of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. The destruction of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous is now thought to have been caused by a single impact event off the coast of Yucatan, Mexico. This asteroid or comet impact led to the deposition of extra-terrestrial iridium, forming the famous K/T boundary in the rock strata of that period.

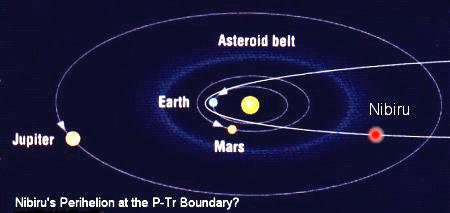

Can we look to a similar cause for the more

catastrophic P-Tr boundary mass extinction?

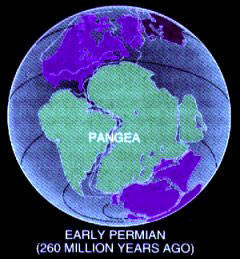

Paleontologists have recorded 4 distinct extinction episodes during the Permian, over a 10 million-year period. At a loss to explain such a bizarre extinction pattern, paleontologists considered the coalescing of the continents into the super-continent ‘Pangea’ to be a likely cause. Ice caps were also forming at that time.

However, this is an unsatisfactory theory, as Richard Corfield notes:

How did the world’s entire ocean become overturned, driving multiple extinction events over a 10 million year period?

The devastation of the P-Tr boundary is so great that internal environmental readjustments simply don’t provide a satisfactory answer. Instead, an extra-terrestrial cause is necessary to meet the fundamental and sustained changes affecting Earth during the Permian. But an asteroid impact is insufficient.

What else is

there?

A lurch into a new terrestrial orbit might provide the mechanism for the over-turning of the oceans, the coalescing of the continents, and the formation of ice caps. What’s more, repeated passages of the brown dwarf through the inner solar system, during its 10 million year long temporary tightly bound orbit, would endanger Earth again and again.

Such an end-game

orbital change would also have significantly affected the Earth

environmentally, leading our world into the Triassic.

The perihelion distance of Nibiru, in other words, is a

variable, and the Permian might have witnessed its closest and most

devastating series of passages.

The Precambrian-Cambrian boundary 540 million years ago represented a colossal sea-change in the development of life on Earth. The sudden emergence of an immense diversity of life forms at that time is known as the Cambrian Explosion, but paleontologists now consider it likely that life was already highly variable prior to this important geological boundary.

The boundary itself indicates a massive carbon isotope

shift, implying ‘profound extinctions among latest Proterozoic life’.

But what could account for such a fundamental climate shift that witnessed glaciers forming over the equator? It is thought that the break-up of the then super-continent ‘Rodinia’ may have contributed to this effect, spreading the broken-up continents around the equator.

This increased the

global ratio of sea to land and brought about increased rainfall which, in

turn, scrubbed out the carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. A positive

feedback cycle then led to a series of glaciations around the globe.

The

‘Snowball Earth’ scenario prior to the Precambrian/Cambrian boundary is

an extreme environmental condition calling out for a bold explanation.

The

cratered appearance of the Moon is largely due to this intense bombardment

of space debris that spiked between 3.8 and 3.9 billion years ago, and the

Earth similarly suffered the most cataclysmic bombardment in its history.

This was said to have occurred about 4 billion years ago, some time after the solar system had formed. I think this ‘late, great bombardment’ is the work of an interstellar brown dwarf that came through the early solar system as a passing failed star. The subsequent interaction with the planets and the Sun resulted in its capture, and a sustained bombardment of cosmic debris.

But this is where I think Sitchin’s account is insufficient, because

the very nature of the cataclysm was a temporary one, lasting at most 100

million years.

The answer lies in the notion that the brown dwarf orbit calculated by Hills is a temporary one. If the logic of astrophysicists like Matese and Whitmire is to be applied, then this captured brown dwarf underwent massive orbital expansion, eventually locating it safely into the outer Oort Cloud. At that distance it could do no more than shower down a few long period comets, most of which would be intercepted by the solar system’s sweeper, Jupiter.

The bombardment had ended after within a 100 million years, and the brown dwarf had taken on a slow, distant orbit around the Sun. But, as we have seen, this was not the end of the story.

More extinction events were to manifest themselves in the

geological record, taking on peculiar attributes.

The theoretical models for such a planetary intrusion predict eccentric orbital properties, but for only a limited number of orbits. Where some might argue that a planet in such an unstable orbit might fall into the Sun, or be ejected outright from the solar system, I would argue a middle position between these two extremes.

The dark star

orbit simply changes from one phase to another, and these phase changes are

what brings about the cataclysms we have seen on Earth at some of the epoch

boundaries described above.

But the capture of an inter-stellar body surely would have taken place much closer to the Sun itself, or else the brown dwarf would have continued past, oblivious to Sol’s influence. Whitmire thinks that comets expand out into the Oort cloud, and that the giant planet would have done the same, whether captured or not. I think he is right.

The dark star was captured and enjoyed a short-lived

honeymoon of destruction in the planetary zone before drifting out into the

comet clouds.

But such discoveries necessarily

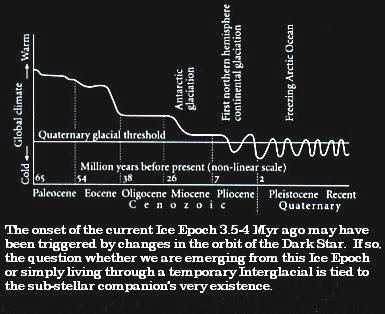

lie some way off.

Since our own planet is the one we have had

opportunity to study most, it is the boundary events between epochs, and the

long period Ice Ages that are not attributed to the Milankovitch cycles,

that grab our attention.

Local planetary conditions might alter the physical manifestation of the effect, but the timing would necessarily be the same.

In this I can make a scientific prediction based upon my hypothesis:

Since the Earth clearly does not intersect the asteroid belt, it is argued that no such collision ever took place. I think the picture is far more dynamic than this. The resonance of planetary orbits indicates how planets can shepherd each other into mutually agreeable configurations, and it seems likely that bodies ‘settle down’ into more stable orbits over time (becoming less eccentric).

I take this further, claiming that a loosely bound planet can be

affected by external influence as well; the galactic tide, passing stars,

gigantic molecular clouds and so on. Its orbit will vary over time,

sometimes drastically as it is perturbed into a new orbital phase. As such,

we can take nothing for granted here at all.

That implies that it must have appeared in the skies, meaning that it has

passed into the planetary zone within Mankind’s collective memory.

Its very presence argues against it being the location

of Nibiru’s perihelion. Nibiru would have acted as a

cosmic vacuum cleaner,

in the same way as Jupiter.

This conclusion may set me at odds with many other Planet X hunters, but I think this is a debate worth starting. There is evidence of Nibiru’s presence in our solar system, and of the devastation it can sometimes unleash, but those events do not fit into a regular pattern of 3600-year intervals, or even 26 million-year intervals.

They are instead sustained

periods of bizarre activity randomly distributed across the geological

record, and are in accordance with an object whose behavior is more that of

a ‘hit-an-run’ perpetrator than a seasoned offender.

This could explain an awful lot about the scant record of Nibiru observation during the historical period, despite its mythological significance. All the more reason to breathe easy about the dark star. It may have caused mass extinctions in the past, but it is unlikely to do so during its current phase.

2003 will be a non-event,

irrespective of the timing of Nibiru.

The belief remains that Planet X will still show up, although the 2003 prediction has been shelved. That's the benefit of hindsight I suppose.

Rather oddly, I have been having further thoughts about Nibiru and how it might be tied in with changes in the Sun's properties, and catastrophic events on Earth, and if anything I have moved towards these guys.

Although I think James McCanney may be taking things a bit too far

with his alternative physics solutions, there may be some truth to the idea

that the Sun's magnetic field is the key to this.

In fact, as I will explain in my

forth-coming book

'Binary

Companion', there may be the potential for a

significant interaction at what most people consider to be the edge of the

solar system...if Nibiru is a sub-brown dwarf.

I'll explain it all in the new book to be

released later this year.

References

|

Our world can also be devastatingly affected by external influence. The

chances of this are very remote, occurring on a time-scale that boggles the

mind.

Our world can also be devastatingly affected by external influence. The

chances of this are very remote, occurring on a time-scale that boggles the

mind.  In 1984, the paleontologists Raup and Sepkoski argued that there is a

cyclical pattern to the extinction events recorded in the fossil record.

In 1984, the paleontologists Raup and Sepkoski argued that there is a

cyclical pattern to the extinction events recorded in the fossil record.

Not just once; but

every time the temporary orbit of the loosely bound cometary dwarf changes.

Not just once; but

every time the temporary orbit of the loosely bound cometary dwarf changes.

Well, the problem is that the extinctions at the

P-Tr boundary did not occur

instantly during a single boundary event (as would be expected if the mass

extinction had been caused by an asteroid impact). They were associated with

multiple events, including the overturning of the oceans, and massive

volcanism.

Well, the problem is that the extinctions at the

P-Tr boundary did not occur

instantly during a single boundary event (as would be expected if the mass

extinction had been caused by an asteroid impact). They were associated with

multiple events, including the overturning of the oceans, and massive

volcanism.  At

the end of the Permian, the unstable temporary orbit might have naturally

degraded, expelling the Dark Star back into the Oort Cloud.

At

the end of the Permian, the unstable temporary orbit might have naturally

degraded, expelling the Dark Star back into the Oort Cloud.  New advances in molecular biology have allowed scientists to back-track

evolutionary progress, and date the various points when great divergence in

life on this planet occurred.

New advances in molecular biology have allowed scientists to back-track

evolutionary progress, and date the various points when great divergence in

life on this planet occurred.  Again, there appears to have been a multiplicity of this phenomenon over a

period of several million years, rather than a single ‘Snowball Earth’

event.

Again, there appears to have been a multiplicity of this phenomenon over a

period of several million years, rather than a single ‘Snowball Earth’

event.

The third catastrophic series of events in the geological record involves a

massive bombardment of the solar system by comets and/or asteroids.

The third catastrophic series of events in the geological record involves a

massive bombardment of the solar system by comets and/or asteroids.  But I think there’s more to this

brown dwarf than just a lone wanderer among

the outer comet clouds. It reappears, and it creates bizarre but temporary

effects in the solar system.

But I think there’s more to this

brown dwarf than just a lone wanderer among

the outer comet clouds. It reappears, and it creates bizarre but temporary

effects in the solar system.  I recently read

'Delicate Earth', a follow-up book about Planet X penned by

Mark Hazelwood.

I recently read

'Delicate Earth', a follow-up book about Planet X penned by

Mark Hazelwood.