|

by

The Europlanet Society

September

22, 2019

from

PHYS Website

Italian version

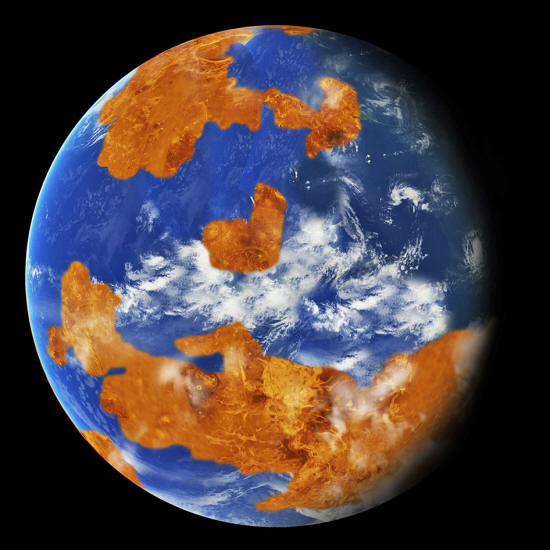

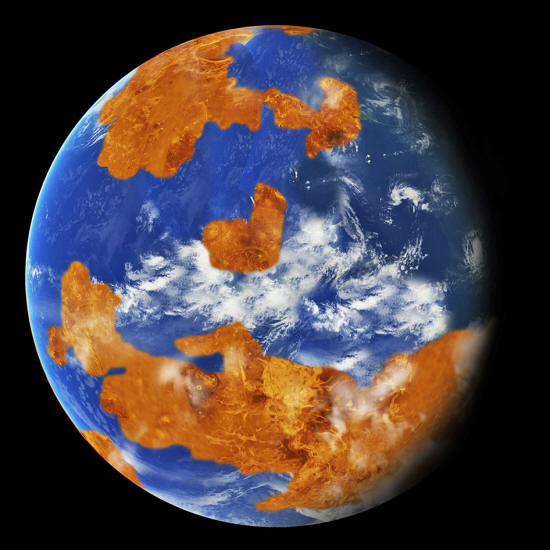

Artist's representation

of

Venus with water.

Credit:

NASA

Venus

may have been a temperate planet hosting liquid water for 2-3

billion years, until a dramatic transformation starting over 700

million years ago resurfaced around 80% of the planet.

A study presented today

at the EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2019 by Michael Way of the

Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS)

gives a new view of Venus's climatic history and may have

implications for the habitability of

exoplanets in similar orbits.

Forty years ago, NASA's

Pioneer Venus mission found

tantalizing hints that Earth's 'twisted sister' planet may once have

had a shallow ocean's worth of water.

To see if Venus might

ever have had a stable climate capable of supporting liquid water,

Dr. Way and his colleague, Anthony Del Genio, have created a

series of five simulations assuming different levels of water

coverage.

In all five scenarios, they found that Venus was able to maintain

stable temperatures between a maximum of about 50 degrees Celsius

and a minimum of about 20 degrees Celsius for around three

billion years...

A temperate climate might

even have been maintained on Venus today had there not been a series

of events that caused a release, or 'outgassing',

of carbon dioxide stored in the rocks of the planet approximately

700-750 million years ago.

"Our hypothesis is

that Venus may have had a stable climate for billions of years.

It is possible that

the near-global resurfacing event is responsible for its

transformation from an Earth-like climate to the hellish

hot-house we see today," said Way.

Three of the five

scenarios studied by Way and Del Genio assumed the topography of

Venus as we see it today and considered a deep ocean averaging 310

meters, a shallow layer of water averaging 10 meters and a small

amount of water locked in the soil.

For comparison, they also

included a scenario with Earth's topography and a 310-metre ocean

and, finally, a world completely covered by an ocean of 158 meters

depth.

To simulate the environmental conditions at 4.2 billion years ago,

715 million years ago and today, the researchers adapted a 3-D

general circulation model to account for the increase in solar

radiation as our Sun has warmed up over its lifetime, as well as for

changing atmospheric compositions.

Although many researchers believe that Venus is beyond the inner

boundary of our Solar System's habitable zone and is too close to

the Sun to support liquid water, the new study suggests that this

might not be the case.

"Venus currently has

almost twice the solar radiation that we have at Earth.

However, in all the

scenarios we have modeled, we have found that Venus could still

support surface temperatures amenable for liquid water," said

Way.

At 4.2 billion years ago,

soon after its formation, Venus would have completed a period of

rapid cooling and its atmosphere would have been dominated by

carbon-dioxide.

If the planet evolved in

an Earth-like way over the next 3 billion years, the carbon dioxide

would have been drawn down by silicate rocks and locked into the

surface.

By the second epoch

modeled at 715 million years ago, the atmosphere would likely have

been dominated by nitrogen with trace amounts of carbon dioxide and

methane - similar to the Earth's today - and these conditions could

have remained stable up until present times.

The cause of the outgassing that led to the dramatic transformation

of Venus is a mystery, although probably linked to the planet's

volcanic activity.

One possibility is that

large amounts of magma bubbled up, releasing carbon dioxide from

molten rocks into the atmosphere. The magma solidified before

reaching the surface and this created a barrier that meant that the

gas could not be reabsorbed.

The presence of large

amounts of carbon dioxide triggered a runaway

greenhouse effect, which has

resulted in the scorching 462 degree average temperatures found on

Venus today.

"Something happened

on Venus where a huge amount of gas was released into the

atmosphere and couldn't be re-absorbed by the rocks.

On Earth we have some

examples of large-scale outgassing, for instance the creation of

the

Siberian Traps 500 million

years ago which is linked to a mass extinction, but nothing on

this scale.

It completely

transformed Venus," said Way.

There are still two major

unknowns that need to be addressed before the question of whether

Venus might have been habitable can be fully answered.

-

The first relates

to how quickly Venus cooled initially and whether it was

able to condense liquid water on its surface in the first

place.

-

The second

unknown is whether the global resurfacing event was a single

event or simply the latest in a series of events going back

billions of years in Venus's history.

"We need more

missions to study Venus and get a more detailed understanding of

its history and evolution," said Way.

"However, our models

show that there is a real possibility that Venus could have been

habitable and radically different from the Venus we see today.

This opens up all

kinds of implications for exoplanets found in what is called the

'Venus

Zone', which may in fact host liquid water and

temperate climates."

|