|

by Alison Abbott

21 September

2018

from

Nature Website

Spanish version

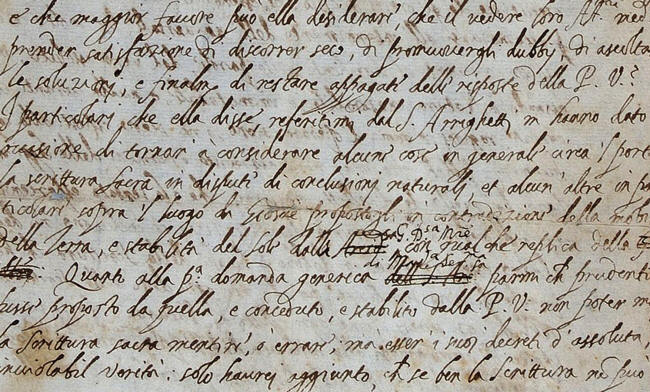

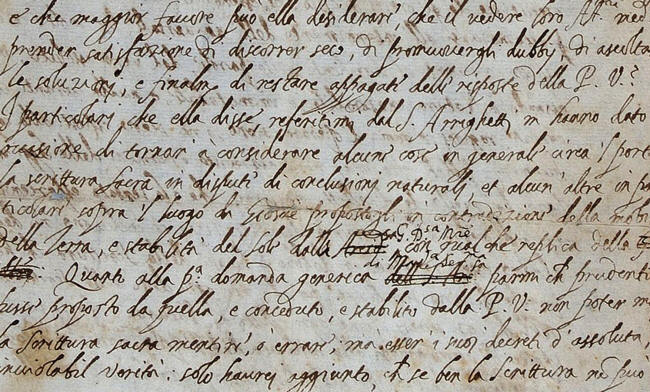

The original letter in which Galileo

argued

against the doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church

has

been rediscovered in London.

Credit:

The Royal Society

Document shows

that the

astronomer toned down the claims

that triggered

science history's

most infamous

battle...

...then lied

about

It had been hiding in plain sight.

The original letter -

long thought lost - in which

Galileo Galilei first set down

his arguments against the church's doctrine that 'the Sun orbits

the Earth' has been discovered in a misdated library catalogue

in London.

Its unearthing and

analysis expose critical new details about the saga that led to the

astronomer's condemnation for 'heresy' in 1633.

The seven-page letter, written to a friend on 21 December 1613 and

signed "G.G.", provides the strongest evidence yet that, at the

start of his battle with the religious authorities, Galileo actively

engaged in damage control and tried to spread a toned-down version

of his claims.

Many copies of the letter were made, and two differing versions

exist:

But because the original

letter was assumed to be lost, it wasn't clear whether incensed

clergymen had doctored the letter to strengthen their case for

heresy - something Galileo complained about to friends - or whether

Galileo wrote the strong version, then decided to soften his own

words.

Galileo did the editing, it seems...

The newly unearthed

letter is dotted with scorings-out and amendments - and handwriting

analysis suggests that Galileo wrote it. He shared a copy of this

softened version with a friend, claiming it was his original, and

urged him to send it to

the Vatican.

The letter has been in

the Royal Society's possession for

at least 250 years, but escaped the notice of historians.

It was rediscovered in

the library there by Salvatore Ricciardo, a postdoctoral

science historian at the University of Bergamo in Italy, who visited

on 2 August for a different purpose, and then browsed the online

catalogue.

"I thought, 'I can't

believe that I have discovered the letter that virtually all

Galileo scholars thought to be hopelessly lost'," says Ricciardo.

"It seemed even more

incredible because the letter was not in an obscure library, but

in the Royal Society library."

Ricciardo, together with

his supervisor Franco Giudice at the University of Bergamo

and science historian Michele Camerota of the University of

Cagliari, describe the letter's details and implications in an

article in press at the Royal Society journal

Notes and Records.

Some science historians

declined to comment on the finding before they had scrutinized the

article.

But Allan Chapman,

a science historian at the University of Oxford, UK, and president

of the Society for the History of Astronomy, says

"it's so valuable -

it will allow new insights into this critical period".

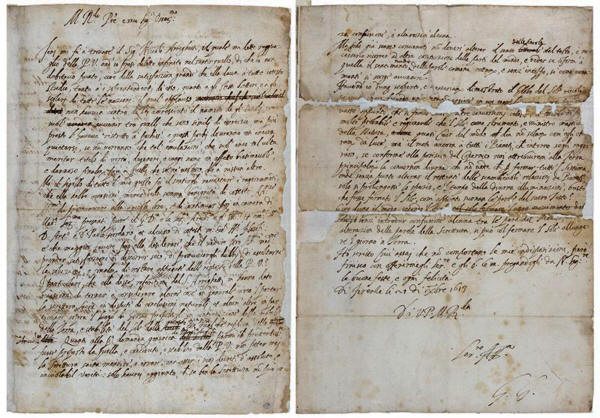

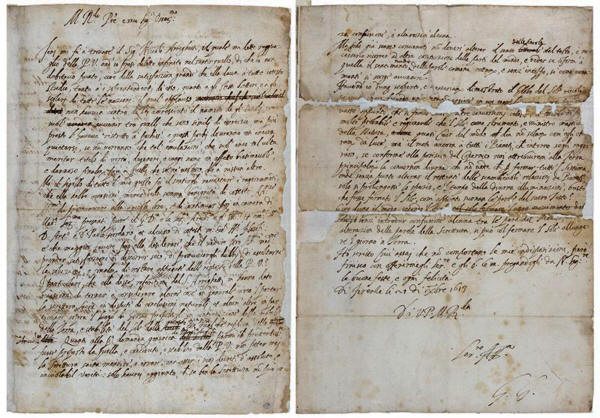

The first and last page of Galileo's letter

to

his friend Benedetto Castelli.

The

last page shows his signature, "G. G.".

Credit:

The Royal Society

Mixed messages

Galileo wrote the 1613 letter to

Benedetto Castelli, a

mathematician at the University of Pisa in Italy. In it, Galileo set

out for the first time his arguments that scientific research should

be free from theological doctrine (see 'The

Galileo Affair').

He argued that the scant references in the Bible to astronomical

events should not be taken literally, because scribes had simplified

these descriptions so that they could be understood by common

people. Religious authorities who argued otherwise, he wrote, didn't

have the competence to judge.

Most crucially, he

reasoned that the heliocentric model of Earth orbiting the Sun,

proposed by Polish astronomer

Nicolaus Copernicus 70 years

earlier, is not actually incompatible with the Bible.

Galileo, who by then was living in Florence, wrote thousands of

letters, many of which are scientific treatises. Copies of the most

significant were immediately made by different readers and widely

circulated.

His letter to Castelli caused a storm.

Of the two versions known to survive, one is now held in the Vatican

Secret Archives. This version was sent to the Inquisition in Rome on

7 February 1615, by a Dominican friar named

Niccol˛ Lorini.

Historians know that

Castelli then returned Galileo's 1613 letter to him, and that on 16

February 1615 Galileo wrote to his friend

Pietro Dini, a cleric in Rome,

suggesting that the version Lorini had sent to the Inquisition might

have been doctored.

Galileo enclosed with

that letter a less inflammatory version of the document, which he

said was the correct one, and asked Dini to pass it on to Vatican

theologians.

His letter to Dini complains of the,

"wickedness and

ignorance" of his enemies, and lays out his concern that the

Inquisition "may be in part deceived by this fraud which is

going around under the cloak of zeal and charity".

Painting of

Galileo explaining his theories

Galileo's celestial ideas

were

deemed heretical

and he

lived his final nine years

under

house arrest.

Credit:

DeAgostini/Getty

At least a dozen copies of the version Galileo sent to Dini are now

held in different collections.

The existence of the two versions created confusion among scholars

over which corresponded to Galileo's original.

Beneath its scratchings-out and amendments, the signed copy

discovered by Ricciardo shows Galileo's original wording - and it is

the same as in the Lorini copy.

The changes are telling.

In one case, Galileo

referred to certain propositions in the Bible as,

"false if one goes by

the literal meaning of the words".

He crossed through the

word "false", and replaced it with "look different from the truth".

In another section, he

changed his reference to the Scriptures,

"concealing" its most

basic dogmas, to the weaker "veiling".

This suggests that

Galileo moderated his own text, says Giudice.

To be certain that the

letter really was written in Galileo's hand, the three researchers

compared individual words in it with similar words in other works

written by Galileo around the same time.

Timeline - The Galileo affair

-

1543 - Polish

astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus publishes his book

On the Revolutions of the Heavenly

Spheres, which proposes that the planets

orbit the Sun.

-

1600 -

The Inquisition in Rome

convicts Dominican friar and mathematician

Giordano Bruno of

heresy on multiple counts, including supporting and

extending the Copernican model. Bruno is burnt at the stake.

-

1610 - Galileo

publishes his book

The Starry Messenger (Sidereus

nuncius), describing discoveries made with his newly built

telescope that provide evidence for the Copernican model.

-

1613 - Galileo

writes a letter to his friend Benedetto Castelli, arguing

against the doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church in matters

of astronomy. Copies of this letter are circulated.

-

1615 - Dominican

friar Niccol˛ Lorini forwards a copy of the letter to the

inquisition in Rome. Galileo asks a friend to forward what

he claims to be a copy of his original letter to Rome; this

version is less inflammatory than Lorini's.

-

1616 - Galileo is

warned to abandon his support of the Copernican model. Books

supporting the Copernican model are banned. On the

Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres is withdrawn from

circulation pending correction to clarify that it is only a

theory.

-

1632 - Galileo

publishes

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief

World Systems, in which he lays out the

various evidence for and against the Church's Ptolemaic

model of the Solar System, and the Copernican model. The

Inquisition summons Galileo to Rome to stand trial.

-

1633 - Galileo is

convicted on "vehement suspicion of heresy" and the book is

banned. He is issued with a prison sentence, later commuted

to house arrest, under which lived the last nine years of

his life.

Chance

discovery

Ricciardo uncovered the document when he was spending a month this

summer touring British libraries to study any handwritten comments

that readers might have left on Galileo's printed works.

When his one day at the

Royal Society was finished, he idly flicked through the online

catalogue looking for anything to do with Castelli, whose writings

he had recently finished editing.

One entry jumped out at him:

a letter that Galileo

wrote to Castelli.

According to the

catalogue, it was dated 21 October 1613.

When Ricciardo examined

it, his heart leapt. It appeared to include Galileo's own signature,

"G.G."; was actually dated 21 December 1613, and contained many

crossings out.

He immediately

realized the letter's potential importance and asked for permission

to photograph all seven pages.

"Strange as it might

seem, it has gone unnoticed for centuries, as if it were

transparent," says Giudice.

The misdating might be

one reason that the letter has been overlooked by Galileo scholars,

says Giudice.

The letter was included

in an 1840 Royal Society catalogue - but was also misdated

there, as 21 December 1618. Another reason might be that the Royal

Society is not the go-to place in the United Kingdom for this type

of historical document, whose more natural home would have been the

British Library.

The historians are now trying to trace how long the letter has been

in the Royal Society library, and how it arrived there.

They know that it has

been there since at least the mid-eighteenth century, and they have

found hints in old catalogues that it might even have been there a

century or more earlier.

The researchers speculate

that it might have arrived at the society thanks to close

connections between the Royal Society and the

Academy of Experiments in

Florence, which was founded in 1657 by Galileo's students but

fizzled out within a decade or so.

For now, the researchers are stunned by their find.

"Galileo's letter to

Castelli is one of the first secular manifestos about the

freedom of science - it's the first time in my life I have been

involved in such a thrilling discovery," says Giudice.

|