by James Glanz and John Markoff

June 12, 2011

from

NYTimes Website

|

Reporting was contributed by

Richard A. Oppel Jr. and Andrew W. Lehren from New York,

and Alissa J. Rubin and Sangar

Rahimi from Kabul, Afghanistan. |

Volunteers have built

a wireless Internet

around Jalalabad,

Afghanistan, from off-the-shelf electronics and ordinary materials

The

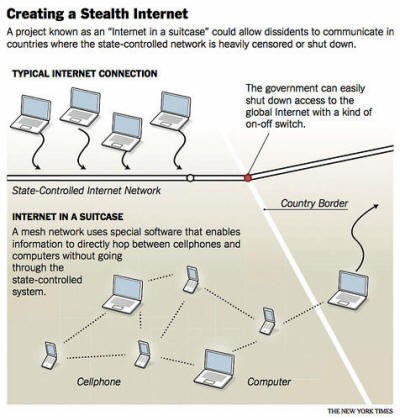

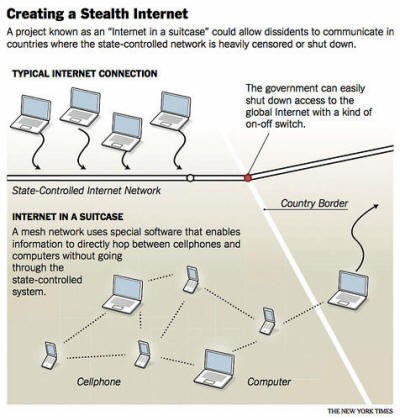

Obama administration is leading a global effort to deploy “shadow”

Internet and mobile phone systems that dissidents can use to undermine

repressive governments that seek to silence them by censoring or shutting

down telecommunications networks.

The effort includes secretive projects to create independent cellphone

networks inside foreign countries, as well as one operation out of a spy

novel in a fifth-floor shop on L Street in Washington, where a group of

young entrepreneurs who look as if they could be in a garage band are

fitting deceptively innocent-looking hardware into a prototype “Internet in

a suitcase.”

Financed with a $2 million State Department grant, the suitcase could be

secreted across a border and quickly set up to allow wireless communication

over a wide area with a link to the global Internet.

The American effort, revealed in dozens of interviews, planning documents

and classified diplomatic cables obtained by The New York Times, ranges in

scale, cost and sophistication.

Some projects involve technology that the United States is developing;

others pull together tools that have already been created by hackers in a

so-called liberation-technology movement sweeping the globe.

The State Department, for example, is financing the creation of stealth

wireless networks that would enable activists to communicate outside the

reach of governments in countries like Iran, Syria and Libya, according to

participants in the projects.

In one of the most ambitious efforts, United States officials say, the State

Department and Pentagon have spent at least $50 million to create an

independent cellphone network in Afghanistan using towers on protected

military bases inside the country. It is intended to offset the Taliban’s

ability to shut down the official Afghan services, seemingly at will.

The effort has picked up momentum since the government of President Hosni

Mubarak shut down the Egyptian Internet in the last days of his rule. In

recent days, the Syrian government also temporarily disabled much of that

country’s Internet, which had helped protesters mobilize.

The Obama administration’s initiative is in one sense a new front in a

longstanding diplomatic push to defend free speech and nurture democracy.

For decades, the United States has sent radio

broadcasts into autocratic countries through Voice of America and other

means. More recently, Washington has supported the development of software

that preserves the anonymity of users in places like China, and training for

citizens who want to pass information along the government-owned Internet

without getting caught.

But the latest initiative depends on creating entirely separate pathways for

communication. It has brought together an improbable alliance of diplomats

and military engineers, young programmers and dissidents from at least a

dozen countries, many of whom variously describe the new approach as more

audacious and clever and, yes, cooler.

Sometimes the State Department is simply taking advantage of enterprising

dissidents who have found ways to get around government censorship. American

diplomats are meeting with operatives who have been burying Chinese

cellphones in the hills near the border with North Korea, where they can be

dug up and used to make furtive calls, according to interviews and the

diplomatic cables.

The new initiatives have found a champion in Secretary of State Hillary

Rodham Clinton, whose department is spearheading the American effort.

Developers caution that independent networks come with downsides: repressive

governments could use surveillance to pinpoint and arrest activists who use

the technology or simply catch them bringing hardware across the border.

But others believe that the risks are outweighed

by the potential impact.

“We’re going to build a separate

infrastructure where the technology is nearly impossible to shut down,

to control, to surveil,” said Sascha Meinrath, who is leading the

“Internet in a suitcase” project as director of the Open Technology

Initiative at the New America Foundation, a nonpartisan research group.

“The implication is that this disempowers

central authorities from infringing on people’s fundamental human right

to communicate,” Mr. Meinrath added.

The Invisible Web

In an anonymous office building on L Street in Washington, four unlikely

State Department contractors sat around a table.

-

Josh King, sporting multiple ear piercings and a

studded leather wristband, taught himself programming while working as a

barista.

-

Thomas Gideon was an accomplished hacker.

-

Dan Meredith, a bicycle

polo enthusiast, helped companies protect their digital secrets.

Then there was Mr. Meinrath, wearing a tie as the dean of the group at age

37.

He has a master’s degree in psychology and helped set up wireless

networks in underserved communities in Detroit and Philadelphia.

The group’s suitcase project will rely on a version of “mesh network”

technology, which can transform devices like cellphones or personal

computers to create an invisible wireless web without a centralized hub. In

other words, a voice, picture or e-mail message could hop directly between

the modified wireless devices - each one acting as a mini cell “tower” and

phone - and bypass the official network.

Internet suitcase

Mr. Meinrath said that the suitcase would include small wireless antennas,

which could increase the area of coverage; a laptop to administer the

system; thumb drives and CDs to spread the software to more devices and

encrypt the communications; and other components like Ethernet cables.

The project will also rely on the innovations of independent Internet and

telecommunications developers.

“The cool thing in this political context is

that you cannot easily control it,” said Aaron Kaplan, an Austrian

cybersecurity expert whose work will be used in the suitcase project.

Mr. Kaplan has set up a functioning mesh network

in Vienna and says related systems have operated in Venezuela, Indonesia and

elsewhere.

Mr. Meinrath said his team was focused on fitting the system into the

bland-looking suitcase and making it simple to implement - by, say, using

“pictograms” in the how-to manual.

In addition to the Obama administration’s initiatives, there are almost a

dozen independent ventures that also aim to make it possible for unskilled

users to employ existing devices like laptops or smartphones to build a

wireless network. One mesh network was created around Jalalabad,

Afghanistan, as early as five years ago, using technology developed at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Creating simple lines of communication outside official ones is crucial,

said Collin Anderson, a 26-year-old liberation-technology researcher from

North Dakota who specializes in Iran, where the government all but shut down

the Internet during protests in 2009.

The slowdown made most “circumvention”

technologies - the software legerdemain that helps dissidents sneak data

along the state-controlled networks - nearly useless, he said.

“No matter how much circumvention the

protesters use, if the government slows the network down to a crawl, you

can’t upload YouTube videos or Facebook postings,” Mr. Anderson said.

“They need alternative ways of sharing information or alternative ways

of getting it out of the country.”

That need is so urgent, citizens are finding

their own ways to set up rudimentary networks.

Mehdi Yahyanejad, an Iranian expatriate and

technology developer who co-founded a popular Persian-language Web site,

estimates that nearly half the people who visit the site from inside Iran

share files using Bluetooth - which is best known in the West for running

wireless headsets and the like.

In more closed societies, however, Bluetooth

is used to discreetly beam information - a video, an electronic business

card - directly from one cellphone to another.

Mr. Yahyanejad said he and his research colleagues were also slated to

receive State Department financing for a project that would modify Bluetooth

so that a file containing, say, a video of a protester being beaten, could

automatically jump from phone to phone within a “trusted network” of

citizens. The system would be more limited than the suitcase but would only

require the software modification on ordinary phones.

By the end of 2011, the State Department will have spent some $70 million on

circumvention efforts and related technologies, according to department

figures.

Mrs. Clinton has made Internet freedom into a signature cause. But the State

Department has carefully framed its support as promoting free speech and

human rights for their own sake, not as a policy aimed at destabilizing

autocratic governments.

That distinction is difficult to maintain, said Clay Shirky, an assistant

professor at New York University who studies the Internet and social media.

“You can’t say, ‘All we want is for people

to speak their minds, not bring down autocratic regimes’ - they’re the

same thing,” Mr. Shirky said.

He added that the United States could expose

itself to charges of hypocrisy if the State Department maintained its

support, tacit or otherwise, for autocratic governments running countries

like Saudi Arabia or Bahrain while deploying technology that was likely to

undermine them.

Shadow Cellphone

System

In February 2009, Richard C. Holbrooke and Lt. Gen. John R. Allen were

taking a helicopter tour over southern Afghanistan and getting a panoramic

view of the cellphone towers dotting the remote countryside, according to

two officials on the flight.

By then, millions of Afghans were using

cellphones, compared with a few thousand after the 2001 invasion.

Towers

built by private companies had sprung up across the country. The United

States had promoted the network as a way to cultivate good will and

encourage local businesses in a country that in other ways looked as if it

had not changed much in centuries.

There was just one problem, General Allen told Mr. Holbrooke, who only weeks

before had been appointed special envoy to the region.

With a combination of threats to phone company

officials and attacks on the towers, the Taliban was able to shut down the

main network in the countryside virtually at will. Local residents report

that the networks are often out from 6 p.m. until 6 a.m., presumably to

enable the Taliban to carry out operations without being reported to

security forces.

The Pentagon and State Department were soon collaborating on the project to

build a “shadow” cellphone system in a country where repressive forces exert

control over the official network.

Details of the network, which the military named the Palisades project, are

scarce, but current and former military and civilian officials said it

relied in part on cell towers placed on protected American bases. A large

tower on the Kandahar air base serves as a base station or data collection

point for the network, officials said.

A senior United States official said the towers were close to being up and

running in the south and described the effort as a kind of 911 system that

would be available to anyone with a cellphone.

By shutting down cellphone service, the Taliban had found a potent strategic

tool in its asymmetric battle with American and Afghan security forces.

The United States is widely understood to use cellphone networks in

Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries for intelligence gathering. And the

ability to silence the network was also a powerful reminder to the local

populace that the Taliban retained control over some of the most vital

organs of the nation.

When asked about the system, Lt. Col. John Dorrian, a spokesman for the

American-led International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF, would only

confirm the existence of a project to create what he called an

“expeditionary cellular communication service” in Afghanistan.

He said the project was being carried out in

collaboration with the Afghan government in order to “restore 24/7 cellular

access.”

“As of yet the program is not fully

operational, so it would be premature to go into details,” Colonel

Dorrian said.

Colonel Dorrian declined to release cost

figures. Estimates by United States military and civilian officials ranged

widely, from $50 million to $250 million.

A senior official said that Afghan officials,

who anticipate taking over American bases when troops pull out, have

insisted on an elaborate system.

“The Afghans wanted the Cadillac plan, which

is pretty expensive,” the official said.

Broad Subversive

Effort

In May 2009, a North Korean defector named Kim met with officials at the

American Consulate in Shenyang, a Chinese city about 120 miles from North

Korea, according to a diplomatic cable.

Officials wanted to know how Mr.

Kim, who was active in smuggling others out of the country, communicated

across the border.

“Kim would not go into much detail,” the

cable says, but did mention the burying of Chinese cellphones “on

hillsides for people to dig up at night.”

Mr. Kim said Dandong, China, and the surrounding

Jilin Province,

“were natural gathering points for

cross-border cellphone communication and for meeting sources.”

The cellphones are able to pick up signals from

towers in China, said Libby Liu, head of Radio Free Asia, the United

States-financed broadcaster, who confirmed their existence and said her

organization uses the calls to collect information for broadcasts as well.

The effort, in what is perhaps the world’s most closed nation, suggests just

how many independent actors are involved in the subversive efforts.

From the

activist geeks on L Street in Washington to the military engineers in

Afghanistan, the global appeal of the technology hints at the craving for

open communication.

In a chat with a Times reporter via Facebook, Malik Ibrahim Sahad, the son

of Libyan dissidents who largely grew up in suburban Virginia, said he was

tapping into the Internet using a commercial satellite connection in

Benghazi.

“Internet is in dire need here. The people

are cut off in that respect,” wrote Mr. Sahad, who had never been to

Libya before the uprising and is now working in support of rebel

authorities.

Even so, he said,

“I don’t think this revolution could have

taken place without the existence of the World Wide Web.”