'

'

by Brian Fung

October 3, 2013

from

WashintongPost Website

|

Brian Fung covers technology

for The Washington Post, focusing on electronic privacy, national

security, digital politics and the Internet that binds it all

together. He was previously the technology correspondent for

National Journal and an associate editor at the Atlantic. His

writing has also appeared in Foreign Policy, Talking Points Memo,

the American Prospect and Nonprofit Quarterly. |

When your browser landed on this article, it didn't just talk to the

friendly servers at washingtonpost.com.

It also made contact with Chartbeat, a company

that helps us understand where else you've been on the Web, and how you're

interacting with the site. Your browser also connected to a personalized

news applet called Trove, various marketing plug-ins and a social

bookmarking service run by a company known as AddThis.

The same is true of the vast majority of sites you'll visit today.

Third-party trackers are watching practically everything you do online. Some

are innocuous in that they help enhance your Web experience. Others are

really annoying - things that you, as a consumer, probably wouldn't want

looking over your shoulder.

To help you see which sites are sending your information to third parties,

the folks at Mozilla have designed a way to visualize these trackers. It's

called

Lightbeam. (Unfortunately, the tool works

only on Mozilla's Firefox browser).

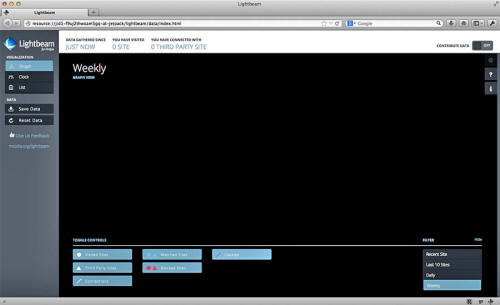

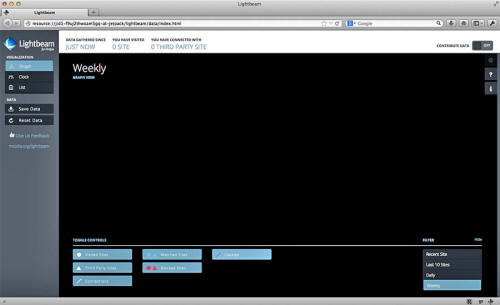

When you launch it, it shows up blank - an empty

canvas waiting for your browsing history to turn it into a detailed online

portrait of you.

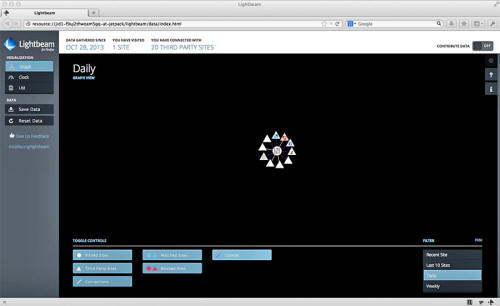

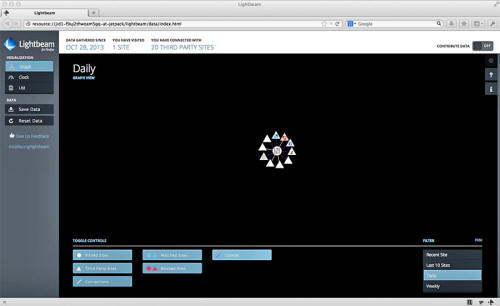

From there, it quickly becomes something of a digital Jackson Pollock. Sites

you visit appear as a white circle. Associated plug-ins branch out from that

circle as white triangles.

Here's what happens when you visit Nordstrom.com,

for instance:

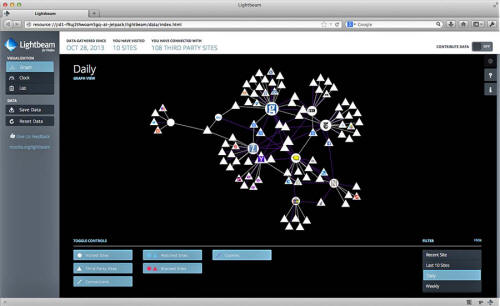

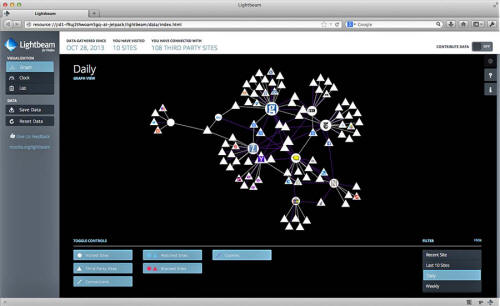

And here's what it looks like when you've visited more than a few sites:

In just the 10 sites that I visited over the course of that session you see

above, my browser made contact with over 100 third-party sites, some of

which had relationships with each other and were likely passing my data back

and forth.

It's an engrossing visualization of a part of the Internet people rarely

see.

There's a whole ecosystem of trackers that

latches on to you in the same way that wood-smoke or the smell of food can

give away where you've been in the physical world recently.

"This is like the Wizard of Oz," says Alex

Fowler, who leads privacy and public policy for Mozilla. "We're pulling

back the curtain here, and this is how the machinery works. This is what

the inner workings of the Web really look like."

So what can consumers do with this information?

Mozilla hopes they'll become more conscious of

the Web's underlying connective tissue. Beyond that, the company doesn't get

much into

specifics.

But Mozilla has also been active in promoting

Firefox's

Do Not Track function, which indicates

to Web sites when a user doesn't want to be tracked. Presumably Lightbeam

and DNT are meant to be complementary:

Once users realize the extent to which

they're being followed, they'll either switch on DNT (which doesn't, by

itself, end the tracking; only the retailer can make that call) or

better yet, become an advocate for a

national Do-Not-Track policy, whose

prospects have been flagging of late.

The likelihood that Mozilla could convert an

average consumer into an effective lobbyist this way - and wind up

succeeding in what's still an obscure policy fight - seems remote.

Still, the organization has a great deal to gain

from describing, in easily understood visual terms, a previously abstruse

and impenetrable side of the Internet.