|

by Robin Koerner

May 02, 2017

from

HuffingtonPost Website

Beware of Orwell's 'Enlightened Class' - Know

Them by Their Fruit

Orwell

understood the Technocrat mind:

"So

'enlightened' that they cannot understand

the most ordinary emotions."

Today, this

is the norm among would-be social engineers who

think it their right or obligation to control

everything and everyone in the environment.

Source

It's Not What

You Believe - It's How You Believe It

George Orwell's novel

1984 has been selling in large

numbers to people scared of a lurch toward authoritarianism in the

USA.

I recently noted that

both that book and

Animal Farm were written not as a

warning against a particular political ideology but against the

implementation of any ideology, however progressive, by people who

think themselves too smart to have to test their politics against

the emotions, sentiments, and experiences of those they would

affect.

In his essay,

My Country Right or Left,

Orwell referred to such people as,

"so 'enlightened'

that they cannot understand the most ordinary emotions."

He understood that the

morality of a political ideology in practice cannot be determined

from its theoretical exposition - but only from the actual

experiences of those who would be affected by its real-world

application.

1984 warned not about a political ideology, but rather, commitment

to an ideology.

To make the point to the people he felt most needed to hear it,

Orwell, a self-identified socialist, called out the arrogance of his

friends on the Left who experienced themselves as so "enlightened,"

to use his word, that they did not need to consider the sentiments -

let alone ideas - of those who were to them clearly politically

ignorant.

Orwell had a name for this kind of self-righteous certainty - and it

wasn't fascism, capitalism, or communism.

It was "orthodoxy,"

which he explains in 1984,

"means not thinking -

not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness."

It is a state exhibited

by people who already know they have the right answers - at least in

the areas that matter.

There is no political system so perfect that it will not be deadly

when imposed against the will of others by people sure of their own

righteousness.

Orwell saw that no

political theory - even the egalitarian socialism that he believed

to be the most moral - can prevent its adherents from being anything

other than tyrants if they are committed to it in a way that is

immune to the protests and experiences of other people.

In other words, tyranny is not the result of a belief in a bad

political theory; it is the result of a bad belief in a political

theory - and that is an entirely different thing.

The

Epistemology of Political Ideologies

To understand tyranny, then, we need to think a bit less

about politics, and a bit more about

epistemology. Epistemology concerns

the nature of knowledge, and especially its formation,

justification, and scope.

Accordingly, the word

"epistemic" means,

"relating to

knowledge or the degree of its validation".

We may be able to

identify one ideology as more consistent with freedom than another,

but that is just an academic exercise if in practice it is the

nature of the commitment to the ideology, rather than the content

committed to, that leads to authoritarianism.

Newton was doing physics, but his work clearly implied a

certain metaphysics.

As Yogi Berra rather nicely put it,

"In theory, there's

no difference between theory and practice; but in practice,

there is."

Can we identify an

epistemology of tyranny?

Is there a mechanism by

which a certain kind of cognitive commitment to a political or moral

theory might cause someone willingly to harm others in its pursuit;

prevent them from seeing the harm they are doing, or even make

invisible to them the data that would demand a revision of their

beliefs to better reflect human experience and lead to outcomes more

aligned with their stated goals?

Such fundamental questions concern our ability to form knowledge and

change our opinions and so both depend on, and reveal, much about

human nature. And since human nature doesn't change, we shouldn't be

too surprised to find that history provides a useful guide in

answering them.

Orwell referred sarcastically to the "enlightenment" of people who

are rather less enlightened than they believe themselves to be.

At first blush, then, it may appear to be a rather remarkable

coincidence that the period of history that perhaps sheds most light

on what makes commitment to ideology dangerous is the Enlightenment.

(But we'll soon see that

it isn't a coincidence at all.)

Knowledge Is

Dangerous

In the latter part of the 17th century, René Descartes,

Isaac Newton, and myriad other intellectual giants were

making a whole new world.

In

Principia Mathematica,

published in 1687, Newton presented the Laws of Motion, the theory

of gravity and even a set of "Rules for Reasoning in Philosophy."

His work explained and

predicted an infinity of (although by no means all) phenomena that

had theretofore been mysterious. In providing a coherent means of

understanding many complex phenomena in terms of a few axioms and

principles, he made tractable a huge swathe of the world.

In as much as Newton's theories substantially described and

predicted things that had not been accurately described or predicted

before, they were both true and useful - or, at least they were much

"truer" than any understanding of the world that had come before it.

Newton was doing physics, but his work clearly implied a certain

metaphysics.

Newton's explanations,

and therefore the underlying reality, were deterministic - meaning

that if you knew the laws that governed things and their state at

one instance, then you could predict in principle their motions and

states at all times.

They rested on

common-sense, observable, causation - meaning that a specific cause

necessarily leads to a specific effect.

They used a common-sense

framework of time and space, in which a foot is always a foot and a

second is always a second, everywhere and always. In one fell swoop,

Newton's work eliminated the need for any non-physical explanations

of a huge number of terrestrial and celestial phenomena.

It was better than what came before it because whereas, say,

the Church's explanatory entities (God, the

saints, the soul) failed to explain why the world operated as it did

rather than any other way, Newton's explanatory entities (force,

mass etc.) did exactly that. And did so with precision in a manner

that could even be used to steer the world towards specific

outcomes.

Indeed, to many, an explanation that wasn't scientific wasn't even

an explanation.

Some of the critical intellectual groundwork for Newton had been

laid by René Descartes, who not long before, had developed

the mathematical framework that was used by Newton in his

extraordinary endeavor. But more than that, Descartes had pioneered

the skeptical philosophical project, showing the world the nature

and standard of certainty that would have to pertain to any claim

that could even be said to constitute "knowledge" at all.

Between Descartes' having primed the Western world not to believe

things that it didn't actually know, and Newton's appearing to

eliminate the need for non-physical explanations of physical

phenomena, some of the "enlightened ones" started to feel that they

could not just sift fact from non-fact, but could prejudge entire

classes of claims as to whether they need to be taken seriously at

all.

Over the next hundred years, this line of thinking continued.

In 1785, for example,

Coulomb did in the domain of electricity and magnetism what

Newton had done in the domain of mechanics and gravity.

And as science advanced,

so-called former "knowledge" that could not be tested against the

direct experience of physical objects; that invoked non-physical

explanations of anything; that could not be the basis of accurate

predictions of physical phenomena - was seen by some to be no more

than commitments of faith, guesswork, or superstition.

In other words, it wasn't just wrong:

it was of an

altogether lower order - perhaps even derisible - and the people

who advanced it were backward-thinking.

To that part of the

educated classes, every success of science reinforced their

certainty in a clockwork universe, justifying not just disagreement

with, but the dismissal of, any postulates that were not consistent

with the prevailing metaphysics.

Indeed, to many, an explanation that wasn't scientific wasn't even

an explanation.

Of great consequence, a

phenomenon that wasn't amenable to a scientific explanation wasn't

even a real phenomenon, but at best an emergent property of real

(physical) phenomena that could be scientifically explained (such as

particles moving in the brain in reaction to stimuli, according to

deterministic laws).

To some, this new science made

free will no longer free, and no

longer even will.

To many, it turned cats

into machines, because (with the exception of humans who in a still

largely Christian world could be believed to have souls), everything

was a machine.

Kicking a cat became as

acceptable to those people as slamming a door.

And here's where we start to circle back to Orwell.

"You See Only

what You Know"

The cat-kickers of the 18th and 19th century

could see their cats react in pain; they could hear them squeal, but

now they knew something that caused them no longer to take their

cat's apparent experience into account - because it was now only

that - apparent.

That squeal was just a mechanical response of a machine to a

mechanical stimulus. There was no consciousness; there was just a

really complex machine (a cat's brain) inside another really complex

machine (a cat).

Cruelty to cats became acceptable not because cruelty became

acceptable, but because cats ceased to be cats.

But only for the

"enlightened", of course, who knew their science, and could laugh

condescendingly about their sentimental neighbors who worried about

whether their cats were happy because they'd evidently not read any

Descartes or Newton.

The "enlightened" could cut themselves off emotionally from the harm

they could see themselves causing.

So we begin to see how something that only the most "enlightened"

people know can cause them to cut off emotionally from the harm they

could clearly see themselves causing, if only their theory - in

fact, their knowledge - were not in the way.

And it is all utterly

reasonable because their knowledge is the most certain and most

tested of any the world has produced.

These are the people who are literally the most progressive of their

age. In the 18th and 19th centuries, not only

did they have all the certainty of science:

they had it bolstered

by the imprimatur of a Church that told them that cats, not

being human, don't have souls, so machines are the only possible

things left for them to be.

Understanding that people

are made of matter, which follows deterministic rules, many of the

European intelligentsia understandably deduced that rules must

govern human behavior too, so they started looking for them.

It was understood that it was necessary to look at the world to find

the laws that govern it, but once they were found, many

non-scientists forgot about the need to keep testing them against

actual phenomena as they started to exploit those laws to produce

desired outcomes.

By the beginning of the 18th century, we were doing that

with steam engines with amazing results.

Could it be that we could

do it with political systems too, especially if

the increasingly discredited Church was wrong about the

soul, and a human being is just a more complex machine than a steam

engine, but a machine nonetheless?

It certainly appeared to

many enlightened thinkers that society followed statistical laws

that could obviously be exploited by social engineering for our

benefit, just as the physical laws were exploited by mechanical

engineering to produce the steam engine and all the good it had done

for us.

Gustav Le Bon, in the Psychology of Revolutions,

explaining the roots of the terror at the end of the 18th

century in France wrote the following:

The [French]

Revolution was above all a permanent struggle between theorists

who were imbued with a new ideal, and the economic, social and

political laws, which ruled mankind, and which they do not

understand…

Well, quite.

The political orthodoxies that arose from the end of the 18th

century - benign and logical in their exposition, but terrifying in

their application - could only be imposed with such relentless

horror and death because of the confident commitment of people to a

"theory" that "explained" a certain set of effects as following from

certain causes - even as the effects were proving them wrong, if

only they'd been open to them.

But they weren't open to them, because they experienced their own

certainty in their theories, not as a psychological state, which is

all it was, but as the accuracy of the theory in which they were

certain, which is an entirely different thing.

That kind of religious commitment to theory - and commitment can be

religious even when the theory is anything but - doesn't matter much

if you're working with steam engines, but it matters a lot if you're

working with guillotines.

I imprison you so that we may all have liberté. I kill you so

that we may all have égalité.

You'd get it if only you were enlightened enough to

understand the theory that makes sense of it all.

And a century after the French Revolution, the deaths of tens of

millions of Russians would be similarly caused and justified using a

philosophy that purported to be deterministic and rational and

manifesting of all the characteristics that make a theory - like

Newton's laws of motion - a good theory.

In both cases, the evil didn't result from the fact that the theory

was incorrect per se.

It resulted from the fact

that its adherents weren't doing science - recognizing that their

current, best model of the world was a step to a better one that is

taken by revising it to accommodate the world's reaction to its

application - but something called scientism, wherein the current,

best model becomes a fixed doctrine and the best of all possible

models.

In other words, it was the epistemology rather than the political

content that was the problem.

All theories are incorrect because none - not even the best theories

we have - are complete, and they are all conceived in very finite

human minds. But some, like

quantum mechanics, for example, are

really, really good.

They get to be good by

being tested time and time again against data from the real world by

people whose motivation is to find information that will show up all

the ways they are wrong or incomplete, rather than information that

reinforces their current understanding.

And motivation is everything, because it determines not just what

will be found, but even what can be seen.

The

Epistemology of Tyranny

Science and scientism are superficially similar but epistemic

opposites. A true scientist remains

doxastically open.

That means that she works

always on the assumption that her theory is,

-

false or

incomplete

-

will therefore

change

The daily task of science

is to identify the ways in which our current understanding is

lacking. In so doing, science's understanding of the world becomes

less false.

Scientism, in contrast, is doxastically closed. That means that it

identifies our best theory but then behaves as if it is,

-

absolute truth

-

will therefore

not change

Scientism, unlike

science, has no need for data. It is deadly because it always uses

the current paradigm to explain away potentially problematic

observations. (E.g. the cat's squeal isn't telling me it's in pain;

it's confirming that machines, including cats, have predictable

responses to physical stimuli.)

Orwell's "unthinking orthodoxy" is "political scientism."

In my earlier article, I wrote about the authoritarianism of some of

the "Social Justice Warrior" Left today, who would give moral

privilege to groups they identity as victim groups in the name of

eliminating privilege; who would eliminate the free speech of people

with whom they disagree in the name of giving everyone an equal

voice; who equate speech with violence to justify violence against

those who speak.

Bizarre as those paradoxes clearly are, their advocates are not

automatically dangerous if they are open to revising their moral or

political theory in the light of falsifying data or contradictions

in the theory's application.

What makes it all dangerous is that it is allied with an a priori

belief about competing views and political opponents that eliminate

the possibility that any experiences or perspectives could provide

data that could challenge the theory.

If potentially contradictory data can be rejected a priori on

account of being explained away as the result of "fascist",

"racist", "sexist" attitudes, for example, then the theory is

inoculated against the human data against which all political

theories must be tested.

Our social justice warrior friends thus become like those engaged in

scientism two centuries ago.

But instead of rejecting

as "backward" phenomena or interpretations of phenomena that do not

exhibit the required meta-characteristics of determinism,

materialism, etc., they reject as "backward" phenomena or

interpretations of phenomena that do not exhibit the

meta-characteristics of victimhood or privilege.

It's not just the preserve of the Left. This kind of epistemic

"inoculation" happens all over the political spectrum.

The successful defense of truth against the closed epistemology of

scientism, and the successful defense of human happiness against the

closed epistemology of political scientism, depend on knowing

something crucial about it: scientism never feels backward or even

extreme: it necessarily looks and feels modern and progressive.

Those with scientistic attitudes usually experience themselves as

just asserting common sense.

After all, they are doing

no more or less than believing in the claims of science, which have

been tested at every turn, have produced tangible improvements all

around us, and have generated more provable knowledge than any other

method of human enquiry.

Indeed, no educated person post-enlightenment can doubt the advance

of science or, therefore, that deterministic and mechanistic

explanations have succeeded where religious ones, for example, have

failed.

Since these scientistic non-scientists experienced themselves,

rightly, as believing in nothing more than the most certain and

proved human knowledge, if you disagree with them, you aren't just

wrong (which would be allowable), you are intellectually backward.

If you believe in spirit,

whatever that might be, in a mechanistic universe, you aren't just

factually mistaken, you are rejecting human progress; you are

believing in something that isn't just not the case but isn't even

worthy of consideration.

It is a position that is so enticingly and dangerously reasonable.

After all, it is obvious that cause and effect exists. How can there

be any knowledge without it? Every known truth depends on it.

You may experience yourself as conscious, the scientistic

non-scientist believes, but there is obviously an objective reality

that doesn't depend on what you think about it.

You may have different experiences from me and interpret them

differently from me, but if your interpretation of the world

violates that belief, then I don't even have to take it seriously.

In fact, I don't even have to take you seriously. You are not just

wrong; you are intellectually beyond the pale; you are one of the

dangerous ones. You are the one, with your strange pseudo-religious

ideas, who probably has to be stopped by people like me who know

better.

In the French Revolution, they stopped you with blades. In the

Russian Revolution, they stopped you with guns and gulags. And it

was all perfectly in line with the theory - with the theory that the

most intellectually and morally enlightened had formulated and were

applying.

Here is Robespierre's justification of the terror of the

French Revolution:

We must smother the

internal and external enemies of the Republic or perish with it;

now in this situation, the first maxim of your policy ought to

be to lead the people by reason and the people's enemies by

terror.

If the spring of popular government in time of peace is virtue,

the springs of popular government in revolution are at once

virtue and terror:

virtue, without

which terror is fatal; terror, without which virtue is

powerless.

Terror is nothing

other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible; it is therefore

an emanation of virtue; it is not so much a special principle as

it is a consequence of the general principle of democracy

applied to our country's most urgent needs.

It has been said that terror is the principle of despotic

government.

Does your government,

therefore, resemble despotism? Yes, as the sword that gleams in

the hands of the heroes of liberty resembles that with which the

henchmen of tyranny are armed.

Let the despot govern

by terror his brutalized subjects; he is right, as a despot.

Subdue by terror the enemies of liberty, and you will be right,

as founders of the Republic.

The government of the

revolution is liberty's despotism against tyranny.

In other words, it may

seem that the fact that a small group of people is guillotining

thousands is a piece of data against our theory of

fraternité, liberté, and égalité -

but that's just because you are not smart enough or good enough or

committed enough to understand it.

Read Robespierre

until you see that your data can't possibly be the data...

It may seem that the fact that a small group of people are starving

others and putting them in concentration camps is a piece of data

against our theory of each those according to his ability to each

according to his need, and the empowerment of the proletariat - but

that is because you are not smart enough or good enough or committed

enough to understand it.

Read Marx until

you see that your facts can't possibly be the facts.

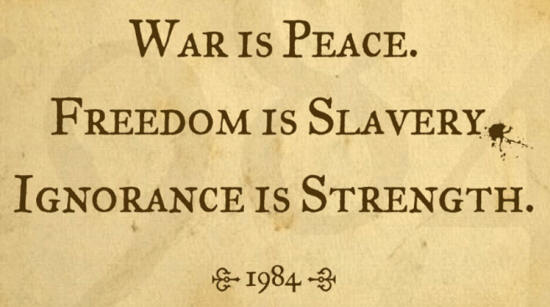

Orwell's "War is peace" and "Freedom is slavery" aren't fiction.

They are history...

The "Knowing"

Changes Everything

At the beginning of the 1920s, as in the decades that preceded it,

some people believed in God and some didn't; some believed in

a human soul and some believed only in human machines, albeit very

sophisticated ones; some believed in cats, and some believed in just

feline machines.

But everyone knew, obviously, that whatever else is true, inanimate

physical matter follows deterministic laws; that the physical

universe is all cause and effect, and that there is an objective

reality out there that carries on just the same regardless of

whether little old me cares to look at it.

I mean, the scientists,

the scientism-ists and the unengaged could at least count on that

certainty, right?

Wrong. All wrong...

In 1925, quantum mechanics happened, and even Einstein, who

not only was one of its pioneers, but had also single-handedly

overturned Newton's common-sense notion of fixed time and space just

a few years before, wasn't sufficiently doxastically open to accept

its implications.

Faced with the end of

determinism, effect without cause, and a physical world that unfolds

in a way determined by conscious observation, he had a rare moment

of scientism when he insisted,

"God does not

play dice with the universe."

But, of course, God

very much does play dice, and the metaphysics that was built on

Newton has been turned on its head.

Scientism is wrong and dangerous because the one unknown thing is

likely to change everything you know.

In so many ways, Newtonian metaphysics looks to science today like

the opposite of the truth, even though Newton's theories are no less

accurate than they were when he wrote Principia. It's just that we

now understand that they are approximate descriptions of

non-deterministic phenomena on large scales.

In other words, they

describe reality, but not its fundamental nature.

That's really important. We've not thrown out all of our past

scientific knowledge:

it's still as

accurate as it was - but in making a slight addition to that

body of knowledge, the fundamental reality that it altogether

implies - has been utterly transformed.

Scientism, including the

political kind, is always wrong and always dangerous because the one

thing that you do not know is likely to change everything you do

know.

Scientism is science stripped of its epistemological core, which is

the knowledge that we don't know.

Those who practice it

think they are "being scientific" because they accept scientific

knowledge. But they are being anything but scientific because they

are committed to those claims in an altogether wrong way - as

knowledge that is both certain and static.

They turn a theory, which by definition, must always be tested

against data that are sought to refute it, into an orthodoxy, which

prevents the data that could refute it from even being perceived.

This is the nature of Orwell's orthodoxy that

1984 was written to warn

us about.

Science is the honest examination of physical objects and their

relationships to understand our world and improve our experience in

it, and scientism is its dogmatic bastardization that causes us to

hold fast to wrong conclusions while,

-

"knowing" that we

are right

-

being unable to

perceive evidence to the contrary

Political science is the

honest examination of people and their relationships to understand

our society and improve our experience in it, and political

scientism is its dogmatic bastardization that causes us to hold fast

to wrong behaviors while,

-

"knowing" that we

are doing good

-

being unable to

act on evidence to the contrary

Regardless of your

scientific theory, scientism destroys human knowledge and makes you

stupid. Regardless of your political ideology, political scientism

destroys human life and makes you dangerous.

Liberty Begins

in Your Head

Want to know if you could become a tyrant?

Don't look at your political beliefs:

Look at your

certainty about them. Look at whether you are more interested in

how to apply your theory or in gathering the data you'd need to

improve it once it's applied.

Look at whether you

are more concerned about the good that you'd do because of what

you know, or the harm that you could do because of what you

don't yet know.

Most of all, consider

whether those who are trying to tell you that the world you want

to live in scares them are presenting you with the data you need

to falsify and therefore improve your political theory (like all

good scientists), or whether you see disregard their objections

as obviously mistaken because, well… you know… the Bible, or

Victims, or the non-aggression principle (depending on your

political stripe).

Spend less time trying to show others why you're right and more

time showing yourself why you're wrong.

If you really want to

live in a world without tyranny, spend less time trying to show

others why you are right and more time trying to show yourself why

you are wrong.

That's not just rhetorical. It's necessary.

Most political arguments that focus on ideological content rather

than commitment to it, end with each party's being yet more certain

about their own rightness and why the other's views need to be

resisted.

So rather than merely opposing your opponent's position, which will

generally elicit a defense of it, and therefore strengthened

commitment to it, practice showing her just how undogmatically you

are committed to your own position, how open you are to experiences

that may challenge it - especially hers.

That doesn't mean that you have to stop advocating living

passionately according to your beliefs any more than scientists have

to stop teaching and building computers because, one day, quantum

mechanics will be superseded, too.

Salesmen know that you have to give some to get some.

If you want someone

to share a personal story with you, share one with them.

If you want someone

to open their mind to your views and experiences, then open your

mind to theirs.

The preservation of

liberty is more about the way we hold our beliefs than the beliefs

that we hold. Tyranny is less a political failure than it is an

epistemological one.

So don't just open your mind to win arguments for liberty - although

that is a critical reason to do so. Do it also because if you don't,

you may start believing you're one of the enlightened ones.

And then you'll be surprised at just how aggressive the peace and

how oppressive the liberty you'll be willing to accept...

|