|

The Atlantis Mystery Excerpted from Mysteries of The Lost Lands

by Eleanor Van Zandt and

Roy Stemman

Where, for a start, was the exact site of this huge island civilization? Did it really, as early historians reported, vanish from the earth in a day and a night? Small wonder that since the earliest times scholars, archaeologists, historians, and occultists have kept up an almost ceaseless search for its precise whereabouts.

Beginning with the Greek

philosopher Plato's first description of the lost land that was apparently

"the nearest thing to paradise on Earth," this chapter examines in detail

the basic evidence for the existence and cataclysmic destruction of

Atlantis.

Said to have been a huge island continent with an extraordinary civilization, situated in the Atlantic Ocean, it is reported to have vanished from the face of the earth in a day and a night. So complete was this devastation that Atlantis sank beneath the sea, taking with it every trace of its existence.

Despite this colossal vanishing trick, the lost continent of Atlantis has exerted a mysterious influence over the human race for thousands of years. It is almost as though a primitive memory of the glorious days of Atlantis lingers on in the deepest recesses of the human mind.

The passage of time has not diminished interest in the fabled continent, nor have centuries of skepticism by scientists succeeded in banishing Atlantis to obscurity in its watery grave. Thousands of books and articles have been written about the lost continent. It has inspired the authors of novels, short stories, poems, and movies.

Its name has been used for ships, restaurants, magazines, and even a region of the planet Mars.

Atlantean societies have been formed to theorize and speculate about a great

lost land. Atlantis has come to symbolize our dream of a once golden past.

It appeals to our nostalgic longing for a better, happier world; it feeds

out hunger for knowledge of mankind's true origins; and above all it offers

the challenge of a genuinely sensational detective story.

Did Atlantis exist, or is it just a myth? Ours may be the

generation that finally solves this tantalizing and ancient enigma.

The earth was rich in precious metals, and the Atlanteans were wealthier than any people before or after with gold, silver, brass, tin, and ivory, and their principal royal palace was a marvel of size and beauty.

Besides being skilled metallurgists, the Atlanteans were

accomplished engineers. A huge and complex system of canals and bridges

linked their capital city with the sea and the surrounding countryside, and

there were magnificent docks and harbors for the fleets of vessels that

carried on a flourishing trade with overseas countries.

In time, however, their noble nature became debased. No longer satisfied with ruling their own great land of plenty, they set about waging war on others. Their vast armies swept through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean region, conquering large areas of North Africa and Europe.

The Atlanteans were poised to strike against Athens and Egypt when the Athenian army rose up, drove them back to Gibraltar, and defeated them.

Hardly had the Athenians tasted victory when a terrible

cataclysm wiped out their entire army in a single day and night, and caused

Atlantis to sink forever beneath the waves. Perhaps a few survivors were

left to tell what happened. At all events, the story is said to have been

passed down through many generations until, more than 9200 years later, it

was made known to the world for the first time.

Although

Plato claimed that the

story of the lost continent was derived from ancient Egyptian records, no

such records have ever come to light, nor has any direct mention of Atlantis

been found in any surviving records made before Plato's time. Every book and

article on Atlantis that has ever been published has been based on Plato's

account; subsequent authors have merely interpreted or added to it.

It has inspired scholars to stake their reputation on the former existence of the lost continent, and explorers to go in search of its remains.

Their actions were prompted not by the Greek story alone, bit also by their own discoveries, which seemed to indicate that there must once have been a great landmass that acted as a bridge between our existing continents.

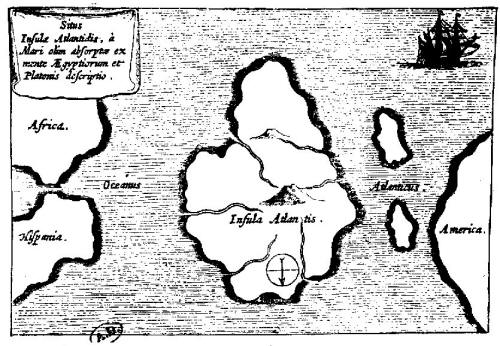

Map of Atlantis by the

17th-century German scholar Athanasius Kircher. Kircher based his

Even without Plato's account, the quest for answers to these mysteries might have led to the belief by some in a 'missing link' between the continents - a land-bridge populated by a highly evolved people in the distant past.

Nevertheless, it is the Greek philosopher's story that lies at the heart of

all arguments for or against the existence of such a lost continent.

Like Plato's other writings, they take the form of dialogues or playlets in which a group of individuals discuss various political and moral issues. Leading the discussion is Plato's old teacher, the Greek philosopher Socrates.

His debating companions are Timaeus, an

astronomer from Italy, Critias, a poet and historian who was a distant

relative of Plato, and Hermocrates, a general from Syracuse.

Plato had

already used the same cat of real-life characters in his most famous

dialogue, The Republic, written some years previously, and he planned his

trilogy as a sequel to that debate, in which the four men had talked at some

length about ideal government.

Then Hermocrates mentions,

Pressed for details, Critias recalls how, a century and a half earlier, the great Athenian statesman Solon had visited Egypt (Solon was a real person and he did visit Egypt, although his trip took place around 590 B.C., so 20 years earlier than the date given by Plato.)

Critias says that while Solon was in Sais, an Egyptian city having close ties with Athens, a group of priests told him the story of Atlantis,

Solon made notes of the conversation, and intended recording the story for posterity, but he did not do so.

Instead he told it

to a relative, Dropides, who passed it on to his son, Critias the elder, who

eventually told his grandson, another Critias - the man who features in

Plato's dialogues.

Beyond it lay a chain of islands that stretched across the ocean to another huge continent.

The Atlanteans ruled over their central island and several others, and over parts of the great continent on the other side of the ocean.

Then their armies struck eastward into the Mediterranean region, conquering North Africa as far as Egypt and southern Europe up to the Greek borders.

Athens, standing alone, defeated the Atlanteans.

Socrates is delighted with Critias' story, which as,

However, the rest of Timaeus is taken up with a discourse on science, and the the story of Atlantis is continued in Plato's next dialogue, the Critias, where Critias gives a much fuller description of the island continent. He goes back to the island's very beginning when the gods were apportioned parts of the earth, as is usual in ancient histories.

Poseidon, Greek god of the sea and also of earthquakes, was given Atlantis, and there he fell in love with a mortal maiden called Cleito.

Cleito dwelled on a hill in Atlantis, and to prevent anyone reaching her home, Poseidon encircled the hill with alternate rings of land and water,

He also laid on abundant supplies of food and water to the hill,

Poseidon and Cleito produced 10 children - five pairs of male twins - and Poseidon divided Atlantis and its adjacent islands among these 10 sons to rule as a confederacy of kings.

The first born of the eldest twins, Atlas

(after whom atlantis was named), was made chief king. The kinds in turn had

numerous children, and their descendants ruled for many generations.

The kings and their descendants built the city of Atlantis around

Cleito's hill on the southern coast of the island continent. It was a

circular city, about 11 miles in diameter, and Cleito's hill, surrounded by

its concentric rings of land and water, formed a citadel about three miles

in diameter, situated at the very center of the impressive city.

The mountains beyond housed,

The inhabitants of the mountains and of the rest of the country were,

These leaders and the

farmers on the plane were each required to supply men for the Atlantean

army, which included light and heavy infantry, cavalry, and chariots.

Critias tells how the stone used for the city's buildings was quarried from beneath the island (Cleito's hill) and from beneath the outer and inner circles of land.

But it was into their magnificent temples that the Atlanteans poured their greatest artistic and technical skills.

In the center of the citadel was a holy artistic and technical skills. In the center of the citadel was a holy temple dedicated to Cleito and Poseidon and this was surrounded by an enclosure of gold. Nearby stood Poseidon's own temple, a superb structure covered in silver, with pinnacles of gold.

The roof's interior was covered with ivory, and lavishly decorated with gold, silver, and orichalcum - probably a fine grade of brass or bronze - which,

Inside the temple was a massive gold statue of Poseidon driving a chariot drawn by six winged horses and surrounded by 100 sea nymphs on dolphins. This was so high that its head touched the temple roof.

Gold statues of Atlantis' original 10 kings and their wives stood outside the temple. Critias tells of the beautiful buildings that were constructed around the warm and cold fountains in the center of the city.

Trees were planted between the buildings, and cisterns were designed - some open to the heavens, others roofed over - to be used as baths.

At alternate intervals of five and six years the 10 kings of Atlantis met in the temple of Poseidon to consult on matters of government and to administer justice. During this meeting a strange ritual was enacted.

After offering up prayers to the gods, the kings were required to hunt bulls, which roamed freely within the temple, and to capture one of them for sacrifice, using only staves and nooses.

The captured animal was led to a bronze column in

the temple, on which the laws of Atlantis were inscribed, and was slain so

that its blood ran over the sacred inscription. After further ceremony, the

kings partook of a banquet and when darkness fell they wrapped themselves in

beautiful dark-blue robes, sitting in a circle they gave their judgments,

which were recorded at daybreak on tablets of gold.

Whereupon, says Plato,

And there, enigmatically, and frustratingly, Plato's story of Atlantis breaks off, never to be completed.

Some regard the Critias dialogue as a

rough draft that Plato abandoned. Others assume he intended to continue the

story in the third part of his trilogy, but he never even started that work.

He went on, instead, to write his last dialogue, The Laws.

Each explanation has

its inherents, and each has been hotly defended over the centuries. Plato's

story certainly presents a number of problems. Critics of the Atlantis

theory claim that these invalidate the story as a factual account.

Supporters maintain that they can be accepted as poetic license,

exaggeration, or understandable mistakes that have crept in during the

telling and retelling of the story over many centuries before Plato reported

it.

Supporters of Atlantis point out that modern discoveries are constantly pushing back the boundaries of human prehistory and we may yet discover that civilization is far older than we think. However, Plato makes it clear that in 9600 B.C., Athens was also the home of a mighty civilization that defeated the Atlanteans.

Archaeologists claim that their knowledge of Greece in the early days of its development is sufficiently complete to rule out the possibility of highly developed people in that country as early as 9600 B.C.

Their evidence suggests that either Plato's story is an invention or he

has the date wrong.

The Egyptian priests are said to have told Solon that a series of

catastrophes had destroyed the Greek records, whereas their own had been

preserved. The problem here is that if the Egyptian disappeared as

completely as Atlantis itself.

However, here again we encounter a difficulty. For whereas in one place

Critias states that he is still in possession of Solon's notes, in another

he declares that he lay awake all night ransacking his memory for details of

the Atlantis story that his grandfather had told him. Why didn't he simply

refresh his memory from Solon's notes? And why didn't he show the notes to

his three companions as incontrovertible proof of the truth of his rather

unlikely story?

Plato may have been present during their conversation, but as he was only

six years old at the time, he could hardly have taken in much of their

discussion, let alone made detailed notes of it. Either his account is based

on records made my someone else, or the date is wrong, or this part of his

story at least is an invention.

He is at great pains to stress the truth of his account, tracing it back to Solon, a highly respected statesman with a reputation for being 'straight-tongues,' and having Critias declare that the Atlantis story, "though strange, is certainly true."

And why, if his sole intention was to deliver a philosophical treatise, did Plato fill his account with remarkable detail and then stop abruptly at the very point where we would expect the "message" to be delivered?

In spite of the errors and

contradictions that have found their way into Plato's account, his story of

Atlantis can still be viewed as an exciting recollection of previously

unrecorded events.

As the Irish scholar J.V. Luce observes in his book The End of Atlantis:

Indeed, Sir Arthur Evans revealed that a highly

advanced European civilization had flourished on the island of Crete long

before the time of Homer, some 4500 years ago.

However, if Plato's account is based on fact, then we know that the Atlanteans traded with their neighbors. In this case there would be some evidence of their influence and culture in lands that survived the catastrophe. Believers in Atlantis have furnished us with a formidable array of such "proofs".

Certainly there are scattered around the glove to lend

support to the idea of a highly advanced, Atlantean-type civilization that

was responsible.

The lost kingdom of Atlantis has been "found" at various times in,

...but to name a few.

|