|

by Peter Doshi

16 May 2013

from

TheRefusers Website

MB Comment

by The Refusers

May 17, 2013

Here is a new hard-hitting

article from the British Medical Journal (BMJ) that

claims the CDC is lying about flu vaccine effectiveness

and destroying its own credibility.

The Refusers obviously agree

with this conclusion. The public needs to wake up and

reject the media onslaught urging annual flu

vaccination.

It’s based on junk science,

commercial interests and outright corruption among

so-called scientific authorities who care more about

feathering their own nests than facts.

Julie Gerberding

Former CDC head, current

chief Merck vaccine huckster

Julie Gerberding

Former CDC

head,

current chief

Merck vaccine huckster

The best example of this sordid

situation is Julie Gerberding, the head of Merck

vaccines (the largest US vaccine manufacturer) - who is the

former head of the CDC.

The CDC mission is

to push vaccines,

no matter how useless and dangerous they may be.

The best career hope for CDC

flunkies is to collaborate with that corrupt program and

make a jump to a better-paid position with a drug company, a

path blazed by vaccine huckster Gerberding.

The entire BMJ article is below, after this brief Q & A with

the author.

Q&A with study author Peter Doshi,

Harvard University

Q) Should we continue to get

the flu shot? What about parents who are trying to

decide for their children?

A) Public health experts are routinely misleading the

public as to the strength of the science in support of

its statements about vaccine effectiveness, safety, and

the threat of influenza… The vaccine is not always

"better than nothing."

Q) Could you comment on the studies that show that

getting the flu shot may not prevent you from getting

sick, but can help prevent you from getting a serious

case?

A) My paper addresses the studies that claim influenza

vaccines reduce the risk of influenza complications. No

good studies support this claim… I would encourage you

to take specific questions to the CDC regarding its

policy.

The CDC pledges,

“To base all public health decisions

on the highest quality scientific data, openly and objectively

derived.”

But Peter Doshi argues that in

the case of influenza vaccinations and their marketing, this is not

so. Promotion of influenza vaccines is one of the most visible and

aggressive public health policies today.

Twenty years ago, in 1990, 32 million

doses of influenza vaccine were available in the United States.

Today around 135 million doses of influenza vaccine annually enter

the US market, with vaccinations administered in drug stores,

supermarkets - even some drive-throughs.

This enormous growth has not been fueled

by popular demand but instead by a public health campaign that

delivers a straightforward,

who-in-their-right-mind-could-possibly-disagree message: influenza

is a serious disease, we are all at risk of complications from

influenza, the flu shot is virtually risk free, and vaccination

saves lives.

Through this lens, the lack of influenza

vaccine availability for all 315 million US citizens seems to border

on the unethical.

Yet across the country, mandatory

influenza vaccination policies have cropped up, particularly in

healthcare facilities,1 precisely because not everyone

wants the vaccination, and compulsion appears the only way to

achieve high vaccination rates.2

Closer examination of influenza vaccine

policies shows that although proponents employ the rhetoric of

science, the studies underlying the policy are often of low quality,

and do not substantiate officials’ claims.

The vaccine might be less beneficial and

less safe than has been claimed, and the threat of influenza appears

overstated.

Now we are all

“at risk” of serious complications

Influenza vaccine production has grown parallel to increases in the

perceived need for the vaccine. In the US, the first recommendations

for annual influenza vaccination were made in 1960 (Table1).

Through the 1990s, the key objective of

this policy was to reduce excess mortality. Because most of

influenza deaths occurred in the older population, vaccines were

directed at this age group. But since 2000, the concept of who is

“at risk” has rapidly expanded, incrementally encompassing greater

swathes of the general population (Box 1 below).

As one US Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) poster picturing a young couple warns:

“Even healthy people can get the

flu, and it can be serious.” 3

Today, national guidelines call for

everyone 6 months of age and older to get vaccinated. Now we are all

“at risk.”

View this table:

Table 1.

Expansion of influenza

vaccination recommendations, 1960 to present

|

Population |

1960 |

1984 |

1987 |

2000 |

2004 |

2006 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|

Recommendations

by age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adults ≥ 65

years |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Adults ≥ 50

years |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Children 6 to 23

months |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Children 6 to 59

months |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Children 6

months to 18 years, if feasible |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Children 6

months to 18 years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

Everyone ≥ 6

months |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Recommendations

by condition or occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pregnant women

(2nd and 3rd trimester) |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Pregnant women

(all trimesters) |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Healthcare

workers |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Household

contacts of high risk groups |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Household

contacts and out of home

caregivers of children 0-23 months |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Household

contacts and out of home

caregivers of children 0-59 months |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Box 1 - A policy without an objective

Despite the enormous sums of money spent fighting the perceived

threat of influenza, there are surprisingly few instances of

unambiguous statements describing the objectives of influenza

vaccination policy.

Here is a sampling, drawn from more than

five decades of influenza vaccination policies in the United States,

that demonstrates the changing purpose of the campaign - from one

with a clear objective of saving older people’s lives, to one

without any stated objective.

In 1964, four years after annual influenza vaccination policies were

first instituted, CDC influenza branch chief Alexander Langmuir and

colleagues wrote that the recommendation,

“was based on three broad

assumptions:

-

That excess mortality was the most important

consequence of epidemic influenza.

-

That polyvalent virus vaccines

had been at least partially effective in preventing clinical illness

during most epidemics and therefore presumably would reduce the risk

of death among the aged and chronically ill.

-

That epidemics

cannot be predicted with sufficient accuracy to permit confident

planning of control measures on a year to year basis.” 4

In 1984,

recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization

Practices stated:

“Because of the increasing proportion of elderly

persons in the United States and because age and its associated

chronic diseases are risk factors for severe influenza illness, the

future toll from influenza may increase, unless control measures are

used more vigorously than in the past...

For about 20 years,

efforts to reduce the impact of influenza in the United States have

been aimed primarily at immunoprophylaxis [vaccination] of persons

at greatest risk of serious illness or death.” 5

Today, the

recommendations do not even mention the effect the policy aims to

achieve.6

Box 2 - Deciphering the numbers

As concern surged this January over a worse than usual influenza

season, members of the media seemed unsure whether the CDC’s

announcement that “vaccine effectiveness (VE) was 62%” 7 represented

good versus disappointing news.8

NBC anchor Brian Williams:

“I worry about this number. I woke up to

reports of this number. It can disincentivize people to go get that

flu shot which all of you are saying is still so important.”

Chief medical editor Nancy Snyderman:

“And I had the same concern

when you see 62%, because I’m afraid people will say ‘well, it’s

half and half.’

But remember, if you have a 62% less chance of

getting of getting the flu, it means less chance of being on

antibiotics, less chance of ending up in an intensive care unit, and

as we’ve seen from this uptick in numbers, 62% less chance of

dying.” 9

Although the study never tested more severe outcomes such as

hospitalizations and death, the logic is nonetheless tempting: if

62% fewer people get influenza, then would not one expect 62% fewer

of all of influenza’s complications? Not necessarily so.

The reason

is that the 62% reduction statistic almost certainly does not hold

true for all subpopulations. In fact, there are good reasons to

assume it does not.

It is well known that influenza infections are

more severe for certain groups of people, such as the frail older

population, compared with others like healthy young adults.

The CDC

study did not present the statistics by age or health status, but an

update of the study released one month later showed 90% of

participants were younger than 65 years, and for older people, there

was no significant benefit (vaccine effectiveness was 27%; 95%

confidence interval, 31% to 59%).10

Not to worry - officials say influenza vaccines save lives

Risk of serious illness is a problem - but, according to the

official narrative, a tractable problem, thanks to vaccines.

As

another CDC poster, this time aimed at seniors, explains:

“Shots

aren’t just for kids. Vaccines for adults can prevent serious

diseases and even death.”11

And in its more technical guidance

document, CDC musters the evidence to support its case. The agency

points to two retrospective, observational studies.

One, a 1995

peer-reviewed meta-analysis published in Annals of Internal

Medicine, concluded:

“many studies confirm that influenza vaccine

reduces the risks for pneumonia, hospitalization, and death in

elderly persons during an influenza epidemic if the vaccine strain

is identical or similar to the epidemic strain.”12

They calculated a

reduction of “27% to 30% for preventing deaths from all causes” -

that is, a 30% lower risk of dying from any cause, not just from

influenza.

CDC also cites a more recent study published in the New

England Journal of Medicine, funded by the National Vaccine Program

Office and the CDC, which found an even larger relative reduction in

risk of death: 48%.13

If true, these statistics indicate that influenza vaccines can save

more lives than any other single licensed medicine on the planet.

Perhaps there is a reason CDC does not shout this from the rooftop:

it’s too good to be true. Since at least 2005, non-CDC researchers

have pointed out the seeming impossibility that influenza vaccines

could be preventing 50% of all deaths from all causes when influenza

is estimated to only cause around 5% of all wintertime deaths.14 15

So how could these studies - both published in high impact, peer

reviewed journals and carried out by academic and government

researchers with non-commercial funding - get it wrong?

Consider one

study the CDC does not cite, which found influenza vaccination

associated with a 51% reduced odds of death in patients hospitalized

with pneumonia (28 of 352 [8%] vaccinated subjects died versus 53

deaths among 352 [15%] unvaccinated control subjects).16

Although

the results are similar to those of the studies CDC does cite, an

unusual aspect of this study was that it focused on patients outside

of the influenza season - when it is hard to imagine the vaccine

could bring any benefit.

And the authors, academics from Alberta,

Canada, knew this: the purpose of the study was to demonstrate that

the fantastic benefit they expected to and did find - and that

others have found, such as the two studies that CDC cites - is

simply implausible, and likely the product of the “healthy-user

effect” (in this case, a propensity for healthier people to be more

likely to get vaccinated than less healthy people).

Others have gone

on to demonstrate this bias to be present in other influenza vaccine

studies.17 18 Healthy user bias threatens to render the

observational studies, on which officials’ scientific case rests,

not credible.

Yet for most people, and possibly most doctors, officials need only

claim that vaccines save lives, and it is assumed there must be

solid research behind it.

But for those that bother to read the

CDC’s national guidelines19 - a 68 page document of 33 360 words and

552 references - one finds that the evidence cited is these

observational studies that the agency itself acknowledges may be

undermined by bias.

The guidelines state:

“...studies demonstrating large reductions in hospitalizations

and deaths among the vaccinated elderly have been conducted using

medical record databases and have not measured reductions in

laboratory-confirmed influenza illness.

These studies have been

challenged because of concerns that they have not controlled

adequately for differences in the propensity for healthier persons

to be more likely than less healthy persons to receive

vaccination.”19

CDC does not rebut or in any other way respond to these criticisms.

It simply acknowledges them, and leaves it at that.

If the observational studies cannot be trusted, what evidence is

there that influenza vaccines reduce deaths of older people - the

reason the policy was originally created? Virtually none.

Theoretically, a randomized trial might shine some light - or even

settle the matter.

But there has only been one randomized trial of

influenza vaccines in older people - conducted two decades ago - and

it showed no mortality benefit (the trial was not powered to detect

decreases in mortality or any complications of influenza).

This

means that influenza vaccines are approved for use in older people

despite any clinical trials demonstrating a reduction in serious

outcomes. Approval is instead tied to a demonstrated ability of the

vaccine to induce antibody production, without any evidence that

those antibodies translate into reductions in illness.

Perhaps most perplexing is officials’ lack of interest in the

absence of good quality evidence.

Anthony Fauci, director of the US

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told the

Atlantic that,

it “would be unethical” to do a placebo controlled

study of influenza vaccine in older people.20

The reason? Placebo

recipients would be deprived of influenza vaccines - that is, the

standard of care, thanks to CDC guidelines.

This is not to say influenza vaccines have no proven benefit. Many

randomized controlled trials of influenza vaccines have been

conducted in the healthy adult population, and a systematic review

found that, depending on vaccine-virus strain match, vaccinating

between 33 and 100 people resulted in one less case of influenza.21

No evidence exists, however, to show that this reduction in risk of

symptomatic influenza for a specific population - here, among

healthy adults - extrapolates into any reduced risk of serious

complications from influenza such as hospitalizations or death in

another population (complications largely occur among the frail,

older population).

This fact seems hard for many health commentators

to grasp, who seem all too ready to take the largest statistic and

apply it to all outcomes for all populations.

At a press briefing

this winter, CDC director Thomas Frieden said a preliminary CDC

study had found,

“the overall vaccine effectiveness to be 62%.”

He

explained that this estimate of relative risk reduction:

“means that

if you got vaccinated you’re about 60% less likely to get the flu

that requires you to go to your doctor.”

On the evening news, the

CDC’s message was translated into a claim that influenza vaccines

will cut the risk of death by 62%, despite the fact that the CDC

study did not even measure mortality (Box 2,

far above).

Reflecting on the same

CDC study, two authors editorialized in the Journal of the American

Medical Association that there exists an irrational pessimism about

influenza vaccine:

“A prevention measure that reduced the risk of a

serious outcome by 60% in most instances would be a noted

achievement; yet for influenza vaccine, it is seen as a ‘failure.’”

Here, too, the authors appear unaware that the CDC study they cite

did not measure any “serious outcome” like pneumonia, only medically

attended acute respiratory illness with influenza confirmed by the

laboratory.

Officials say

influenza vaccines are safe

The CDC’s universal influenza vaccination recommendation carries the

implicit message that, beyond those for whom the vaccine is

contraindicated, influenza vaccine can only do good; there is no

need to weigh risks against benefits.

In October 2009, the US

National Institutes of Health produced a promotional YouTube video

featuring Fauci.

Urging US citizens to get vaccinated against

the

H1N1 influenza, Fauci stressed the vaccine’s safety:

“the track

record for serious adverse events is very good. It’s very, very,

very rare that you ever see anything that’s associated with the

vaccine that’s a serious event.”

Months later, Australia suspended its influenza vaccination program

in under five year olds after many (one in every 110 vaccinated)

children had febrile convulsions after vaccination.

Another serious

reaction to influenza vaccines - and also unexpected - occurred in

Sweden and Finland, where H1N1 influenza vaccines were associated

with a spike in cases of narcolepsy among adolescents (about one in

every 55 000 vaccinated).

Subsequent investigations by governmental

and non-governmental researchers confirmed the vaccine’s role in

these serious events.22 23 24 25

Selling sickness - what’s in a name?

Drug companies have long known that to sell some products, you would

have to first sell people on the disease.

Early 20th century

advertising for the mouthwash Listerine, for example, warned readers

of the problem of “halitosis” - thereby turning bad breath into a

widespread social concern.26

Similarly, in the 1950s and 1960s,

Merck launched an extensive campaign to lower the diagnostic

threshold for hypertension, and in doing so enlarging the market for

its diuretic drug,

Diuril (chlorothiazide).27

Today drug companies

suggest that we have under-diagnosed epidemics of erectile

dysfunction, social anxiety disorder, and female sexual dysfunction,

each with their own convenient acronym and an approved medication at

the ready.

Could influenza - a disease known for centuries, well

defined in terms of its etiology, diagnosis, and prognosis - be yet

one more case of disease mongering? I think it is.

But unlike most

stories of selling sickness, here the salesmen are public health

officials, worried little about which brand of vaccine you get so

long as they can convince you to take influenza seriously.

Marketing influenza vaccines thus involves marketing influenza as a

threat of great proportions.

The CDC’s website explains that,

“Flu

seasons are unpredictable and can be severe,” citing a death toll of

“3000 to a high of about 49 000 people.”

However, a far less

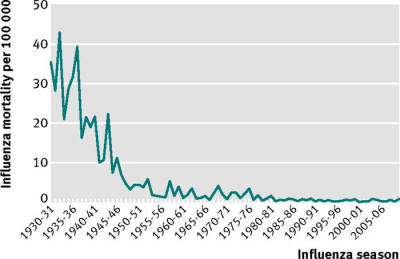

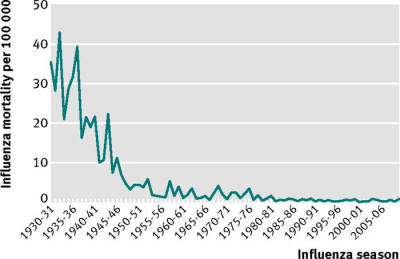

volatile and more reassuring picture of influenza seems likely if

one considers that recorded deaths from influenza declined sharply

over the middle of the 20th century, at least in the United States,

all before the great expansion of vaccination campaigns in the

2000s, and despite three so-called “pandemics” (1957, 1968, 2009)

(fig 1).

Fig 1

Crude mortality per

100 000 population, by influenza season

(July to June of the

following year),

for seasons 1930-31

to 2009-10, US.

Data sources: Doshi

P. Am J Pub Health 2008;98:939-45.

But perhaps the cleverest aspect of the influenza marketing strategy

surrounds the claim that “flu” and “influenza” are the same.

The

distinction seems subtle, and purely semantic.

But general lack of

awareness of the difference might be the primary reason few people

realize that even the ideal influenza vaccine, matched perfectly to

circulating strains of wild influenza and capable of stopping all

influenza viruses, can only deal with a small part of the “flu”

problem because most “flu” appears to have nothing to do with

influenza.

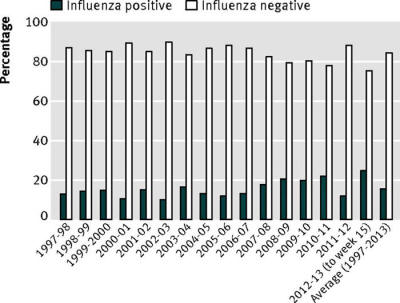

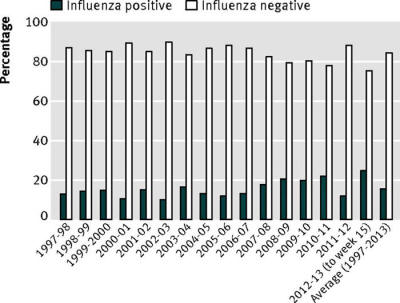

Every year, hundreds of thousands of respiratory

specimens are tested across the US. Of those tested, on average 16%

are found to be influenza positive. (fig 2).

All influenza is “flu,” but only one in six “flues” might be

influenza.

It’s no wonder so many people feel that “flu shots” don’t

work: for most flues, they can’t.

Fig 2

Proportion of

specimens testing positive for influenza at

World Health

Organization (WHO)

Collaborating

Laboratories and National Respiratory

and Enteric Virus

Surveillance System (NREVSS) laboratories

through the United

States.

Data are compiled and

published by CDC.28-43

Notes

Footnotes

-

Acknowledgements: I am grateful

to Yuko Hara, Tom Jefferson, and Edward Davies, for their

comments.

-

Competing interests: I have read

and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of

interests and declare the following interests: PD is a

co-recipient of a UK National Institute for Health Research

grant to carry out a Cochrane review of neuraminidase

inhibitors (http://www.hta.ac.uk/2352). PD received €1500

from the European Respiratory Society in support of his

travel to the society’s September 2012 annual congress where

he gave an invited talk on oseltamivir. He is funded by an

institutional training grant from the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality (AHRQ) #T32HS019488. AHRQ had no role

in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to

publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

-

Provenance and peer review:

commissioned: not externally peer reviewed.

References

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

|