|

by Jeremy Smith

The Ecologist v.35, n.1

1 February 2005

from

MindFully Website

|

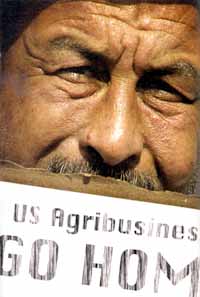

Under the guise of helping

get Iraq back on its feet, the US is setting out to

totally re-engineer the country's traditional farming

systems into a US-style corporate agribusiness. They’ve

even created a new law –

Order 81 – to make sure

it happens. |

Coals to Newcastle. Ice to

Eskimos. Tea to China. These are the acts of the ultimate

salesmen, wily marketers able to sell even to people with no

need to buy.

To that list can now be added a

new phrase - Wheat to Iraq.

Iraq is part of the ‘fertile crescent’

of Mesopotamia.

It is here, in around

8,500 to 8,000BC, that mankind

first 'domesticated' wheat, here that agriculture was born. In recent

years however, the birthplace of farming has been in trouble. Wheat

production tumbled from 1,236,000 tons in 1995 to just 384,000 tons

in 2000.

Why this should have happened very much

depends on whom you ask.

A press release from Headquarters United States Command reports

that,

‘Over the past 10 years, this region

has not been able to keep up with Iraq’s wheat demand. During

the

Saddam Hussein regime, farmers were expected to continuously

produce wheat, never leaving their fields fallow. This tactic

degraded the soil, leaving few nutrients for the next year’s

crop, increasing the chances for crop disease and fungus, and

eventually resulting in fewer yields.’

For the US military, the blame clearly

lies with the ‘tactics’ of ‘Saddam’s regime’.

However, in 1997 the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

found:

‘Crop yields... remain low due to

poor land preparation as a result of lack of machinery, low use

of inputs, deteriorating soil quality and irrigation facilities’

and ‘The animal population has declined steeply due to severe

shortages of feed and vaccines during the embargo years’.

Less interested in selling a war

perhaps, the FAO sees Iraqi agriculture suffering due to a lack of

necessary machinery and inputs, themselves absent as the result of

deprivation ‘during the embargo years’.

Or it could have been simpler still.

According to a 2003 USDA

report,

‘Current total production of major

grains is estimated to be down 50 percent from the 1990/91

level. Three years of drought from 1999-2001 significantly

reduced production.’

Whoever you believe, Iraqi wheat

production has collapsed in recent years. The next question then, is

how to get it back on its feet.

Despite its recent troubles, Iraqi agriculture’s long history means

that for the last 10,000 years Iraqi farmers have been naturally

selecting wheat varieties that work best with their climate.

Each

year they have saved seeds from crops that prosper under certain

conditions and replanted and cross-pollinated them with others with

different strengths the following year, so that the crop continually

improves.

In 2002, the FAO estimated that 97 per

cent of Iraqi farmers used their own saved seed or bought seed from

local markets.

That there are now over 200,000 known

varieties of wheat in the world is down in no small part to the

unrecognized work of farmers like these and their informal systems

of knowledge sharing and trade.

It would be more than reasonable to

assume that somewhere amongst the many fields and grain-stores of

Iraq there are samples of strong, indigenous wheat varieties that

could be developed and distributed around the country in order to

bolster production once more.

Likewise, long before Abu Ghraib became the world’s most infamous

prison, it was known for housing not inmates, but seeds. In the

early 1970s samples of the many varieties used by Iraqi farmers were

starting to be saved in the country’s national gene bank, situated

in the town of Abu Ghraib.

Indeed one of Iraq’s most well known

indigenous wheat varieties is called ‘Abu Ghraib’.

Unfortunately, this vital heritage and knowledge base is now

believed lost, the victim of the current campaign and the many years

of conflict that preceded it. But there is another viable source. At

the

International Centre for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas

(ICARDA) in Syria there are still samples of several Iraqi

varieties.

As a revealing report by Focus on

the Global South and GRAIN comments:

‘These comprise the agricultural

heritage of Iraq belonging to the Iraqi farmers that ought now

to be repatriated.’

If Iraq’s new administration truly

wanted to re-establish Iraqi agriculture for the benefit of the

Iraqi people it would seek out the fruits of their knowledge.

It

could scour the country for successful farms, and if it miraculously

found none could bring over the seeds from ICARDA and use those as

the basis of a program designed to give Iraq back the agriculture it

once gave the world.

The US, however, has decided that, despite 10,000 years practice,

Iraqis don’t know what wheat works best in their own conditions, and

would be better off with some new, imported American varieties.

Under the guise, therefore, of helping

get Iraq back on its feet, the US is setting out to totally

reengineer the country’s traditional farming systems into a US-style

corporate agribusiness.

Or, as the aforementioned press release

from Headquarters United States Command puts it:

‘Multi-National Forces are currently

planting seeds for the future of agriculture in the Ninevah

Province’

First, it is re-educating the farmers.

An article in the Land and Livestock

Post reveals that thanks to a project undertaken by Texas A&M

University’s International Agriculture Office there are now 800

acres of demonstration plots all across Iraq, teaching Iraqi farmers

how to grow ‘high-yield seed varieties’ of crops that include

barley, chick peas, lentils – and wheat.

The leaders of the $107 million project have a stated goal of

doubling the production of 30,000 Iraqi farms within the first year.

After one year, farmers will see soaring production levels. Many

will be only too willing to abandon their old ways in favor of the

new technologies.

Out will go traditional methods. In will

come imported American seeds (more than likely GM, as Texas A&M's

Agriculture Program considers itself ‘a recognized world leader in

using biotechnology’). And with the new seeds will come new

chemicals – pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, all sold to the

Iraqis by corporations such as

Monsanto, Cargill and Dow.

Another article, this time in

The Business Journal of Phoenix,

declares:

‘An Arizona agri-research firm is

supplying wheat seeds to be used by farmers in Iraq looking to

boost their country's homegrown food supplies.’

That firm is called the

World Wide

Wheat Company (WWWC), and in partnership with three

universities (including Texas A&M again) it is to ‘provide 1,000

pounds of wheat seeds to be used by Iraqi farmers north of Baghdad.’

According to

Seedquest (described as the ‘central information

website for the global seed industry’) WWWC is one of the leaders in

developing proprietary varieties of cereal seeds - i.e. varieties

that are owned by a particular company. According to the firm’s

website, any ‘client’ (or farmer as they were once known) wishing to

grow one of their seeds, ‘pays a licensing fee for each variety’.

All of a sudden the donation doesn’t sound so altruistic. WWWC gives

the Iraqis some seeds. They get taught how to grow them, shown how

much ‘better’ they are than their seeds, and then told that if they

want any more, they have to pay.

Another point in one of the articles casts further doubt on American

intentions.

According to the Business Journal,

‘six kinds of wheat

seeds were developed for the Iraqi endeavor. Three will be used for

farmers to grow wheat that is made into pasta; three seed strains

will be for bread-making.’

Pasta?

According to the 2001 World Food Program report on Iraq,

‘Dietary habits and preferences

included consumption of large quantities and varieties of meat,

as well as chicken, pulses, grains, vegetables, fruits and dairy

products.’

No mention of lasagne. Likewise,

a quick check of the Middle Eastern cookbook on my kitchen shelves,

while not exclusively Iraqi, reveals a grand total of no pasta

dishes listed within it.

There can be only two reasons why 50 per cent of the grains being

developed are for pasta. One, the US intends to have so many

American soldiers and businessmen in Iraq that it is orienting the

country’s agriculture around feeding not ‘Starving Iraqis’ but

‘Overfed Americans’. Or, and more likely, because the food was never

meant to be eaten inside Iraq at all.

Iraqi farmers are to be taught to grow crops for export. Then they

can spend the money they earn (after they have paid for next year’s

seeds and chemicals) buying food to feed their family. Under the

guise of aid, the US has incorporated them into the global economy.

What the US is now doing in Iraq has a very significant precedent.

The

Green Revolution of the 1950s and

60s was to be the new dawn for farmers in the developing world. Just

as now in Iraq, Western scientists and corporations arrived

clutching new ‘wonder crops’, promising peasant farmers that if they

planted these new seeds they would soon be rich.

The result was somewhat different.

As Vandana Shiva writes in

Biopiracy - The plunder of nature and knowledge:

‘The miracle varieties displaced the

diversity of traditionally grown crops, and through the erosion

of diversity the new seeds became a mechanism for introducing

and fostering pests. Indigenous varieties are resistant to local

pests and diseases.

Even if certain diseases occur, some of the

strains may be susceptible, but others will have resistance to

survive.’

Worldwide, thousands of traditional

varieties developed over millennia were forsaken in favor of a few

new hybrids, all owned by even fewer giant multinationals.

As a result, Mexico has lost 80 per cent

of its corn varieties since 1930. At least 9,000 varieties of wheat

grown in China have been lost since 1949. Then in 1970 in the US,

genetic uniformity resulted in the loss of almost a billion dollars

worth of maize because 80 per cent of the varieties grown were

susceptible to a disease known as ‘southern leaf blight’.

Overall, the FAO estimates that about 75 per cent of genetic

diversity in agricultural crops was lost in the last century.

The impact on small farmers worldwide

has been devastating. Demanding large sums of capital and high

inputs of chemicals, such farming massively favors large scale,

industrial farmers. The many millions of dispossessed people in Asia

and elsewhere is in large part a result of this inequity. They can’t

afford to farm anymore, are driven off their land, either into their

cities’ slums or across the seas to come knocking at the doors of

those who once offered them a poisoned chalice of false hope.

What separates the US’s current scheme from those of the Green

Revolution is that the earlier ones were, at least in part, the

decisions of the elected governments of the countries affected. The

Iraqi plan is being imposed on the people of Iraq without them

having any say in the matter. Having ousted Saddam, America is now

behaving like a despot itself. It has decided what will happen in

Iraq and it is doing it, regardless of whether it is what the Iraqi

people want.

When former Coalition Provisional Authority administrator

Paul Bremer departed Iraq in June 2004 he left behind a legacy

of 100 ‘Orders’ for the restructuring of the Iraqi legal system.

Of these orders, one is particularly

pertinent to the issue of seeds.

Order 81 covers the issues of ‘Patent,

Industrial Design, Undisclosed Information, Integrated Circuits and

Plant Variety.'

It amends Iraq’s original law on

patents, created in 1970, and is legally binding unless repealed by

a future Iraqi government.

The most significant part of Order 81 is a new chapter that

it inserts on ‘Plant Variety Protection’ (PVP). This

concerns itself not with the protection of biodiversity, but rather

with the protection of the commercial interests of large seed

corporations.

To qualify for PVP, seeds have to meet the following criteria: they

must be ‘new, distinct, uniform and stable’.

Under the new

regulations imposed by

Order 81, therefore, the sort of seeds Iraqi

farmers are now being encouraged to grow by corporations such as WWWC will be those registered under PVP.

On the other hand, it is impossible for the seeds developed by the

people of Iraq to meet these criteria. Their seeds are not ‘new’ as

they are the product of millennia of development. Nor are they

‘distinct’. The free exchange of seeds practiced for centuries

ensures that characteristics are spread and shared across local

varieties. And they are the opposite of ‘uniform’ and ‘stable’ by

the very nature of their biodiversity. They cross-pollinate with

other nearby varieties, ensuring they are always changing and always

adapting.

Cross-pollination is an important issue for another reason. In

recent years several farmers have been taken to court for illegally

growing a corporation’s GM seeds.

The farmers have argued they were doing

so unknowingly, that the seeds must have carried on the wind from a

neighboring farm, for example. They have still been taken to court.

This will now apply in Iraq. Under the new rules, if a farmer’s seed

can be shown to have been contaminated with one of the PVP

registered seeds, he could be fined.

He may have been saving his seed for

years, maybe even generations, but if it mixes with a seed owned by

a corporation and maybe creates a new hybrid, he may face a day in

court.

Remember that 97 per cent of Iraqi farmers save their seeds. Order

81 also puts paid to that.

A new line has been added to the law

which reads:

‘Farmers shall be prohibited from

re-using seeds of protected varieties or any variety mentioned

in items 1 and 2 of paragraph (C) of Article 14 of this

Chapter.’

The other varieties referred to are

those that show similar characteristics to the PVP varieties. If a

corporation develops a variety resistant to a particular Iraqi pest,

and somewhere in Iraq a farmer is growing another variety that does

the same, it’s now illegal for him/her to save that seed. It sounds

mad, but it’s happened before.

A few years back a corporation called

SunGene patented a sunflower

variety with a very high oleic acid content. It didn’t just patent

the genetic structure though, it patented the characteristic.

Subsequently SunGene notified other sunflower breeders that

should they develop a variety high in oleic acid with would be

considered an infringement of the patent.

So the Iraqi farmer may have been wowed with the promise of a bumper

yield at the end of this year. But unlike before he can’t save his

seed for the next. A 10,000-year old tradition has been replaced at

a stroke with a contract for hire.

Iraqi farmers have been made vassals to American corporations. That

they were baking bread for 9,500 years before America existed has no

weight when it comes to deciding who owns Iraq’s wheat. Yet for

every farmer that stops growing his unique strain of saved seed the

world loses another variety, one that might have been useful in

times of disease or drought.

In short, what America has done is not restructure Iraq’s

agriculture, but dismantle it. The people whose forefathers first

mastered the domestication of wheat will now have to pay for the

privilege of growing it for someone else.

And with that the world’s oldest farming

heritage will become just another subsidiary link in the vast

American supply chain.

|