|

by Andrew Schneider

Andrew Schneider Senior Public Health

Correspondent

March 24, 2010

from

AOLNews Website

First in a Three-Part Series

Amid Nanotech's Dazzling Promise, Health Risks

Grow

For almost two years, molecular

biologist Bénédicte Trouiller doused the drinking water of

scores of lab mice with nano-titanium dioxide, the most common

nanomaterial used in consumer products today.

She knew that earlier studies conducted in test tubes and petri

dishes had shown the same particle could cause disease. But her

tests at a lab at UCLA's School of Public Health were in vivo -

conducted in living organisms - and thus regarded by some scientists

as more relevant in assessing potential human harm.

Halfway through, Trouiller became alarmed: Consuming the nano-titanium

dioxide was damaging or destroying the animals' DNA and chromosomes.

The biological havoc continued as she repeated the studies again and

again.

It was a significant finding: The

degrees of DNA damage and genetic instability that the 32-year-old

investigator documented can be,

"linked to all the big killers of

man, namely cancer, heart disease, neurological disease and

aging," says Professor Robert Schiestl, a genetic toxicologist

who ran the lab at UCLA's School of Public Health where

Trouiller did her research.

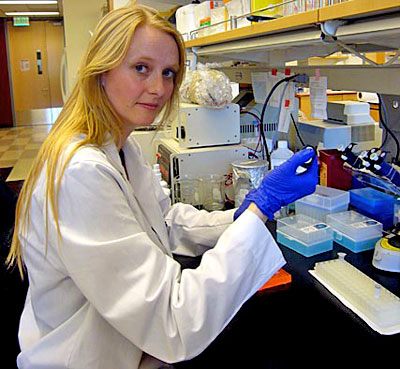

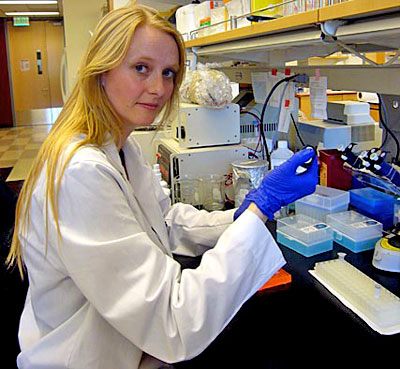

Benedicte Trouiller

in an undated photo

Courtesy Benedicte Trouiller

UCLA

molecular biologist Bénédicte Trouiller found

that nano-titanium dioxide - the nanomaterial

most commonly used in consumer products today -

can damage or destroy DNA and chromosomes at

degrees that can be linked to "all the big

killers of man," a colleague says.

Nano-titanium dioxide is so pervasive

that the Environmental Working Group says it has calculated that

close to 10,000 over-the-counter products use it in one form or

another.

Other public health specialists put the

number even higher.

It's "in everything from medicine capsules and

nutritional supplements, to food icing and additives, to skin

creams, oils and toothpaste," Schiestl says.

He adds that at least 2

million pounds of nanosized titanium dioxide are produced and used

in the U.S. each year.

What's more, the particles Trouiller gave the mice to drink are just

one of an endless number of engineered, atom-size structures that

have been or can be made. And a number of those nanomaterials have

also been shown in published, peer-reviewed studies (more than 170

from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

alone) to potentially cause harm as well.

Researchers have found, for instance,

that

carbon nanotubes - widely used in many industrial applications

- can penetrate the lungs more deeply than asbestos and appear to

cause asbestos-like, often-fatal damage more rapidly.

Other nanoparticles, especially those

composed of metal-chemical combinations, can cause cancer and birth

defects; lead to harmful buildups in the circulatory system; and

damage the heart, liver and other organs of lab animals.

Yet despite those findings, most federal agencies are doing little

to nothing to ensure public safety. Consumers have virtually no way

of knowing whether the products they purchase contain nanomaterials,

as under current U.S. laws it is completely up to manufacturers what

to put on their labels.

And hundreds of interviews conducted by

AOL News' senior public health correspondent over the past 15 months

make it clear that movement in the government's efforts to institute

safety rules and regulations for use of nanomaterials is often as

flat as the read-out on a snowman's heart monitor.

"How long should the public have to

wait before the government takes protective action?" says Jaydee

Hanson, senior policy analyst for the Center for Food Safety.

"Must the bodies stack up first?"

Big Promise

Comes With Potential Perils

"Nano" comes from the Greek word for dwarf, though that falls short

of conveying the true scale of this new world: Draw a line 1 inch

long, and 25 million nanoparticles can fit between its beginning and

end.

Apart from the materials' size, everything about nanotechnology is

huge. According to the federal government and investment analysts,

more than 1,300 U.S. businesses and universities are involved in

related research and development.

The National Science Foundation says

that $60 billion to $70 billion of nano-containing products are sold

in this country annually, with the majority going to the energy and

electronics industries.

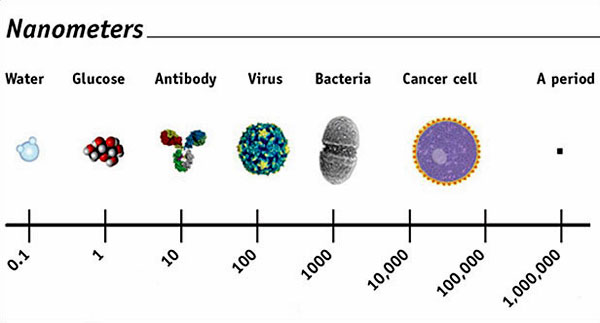

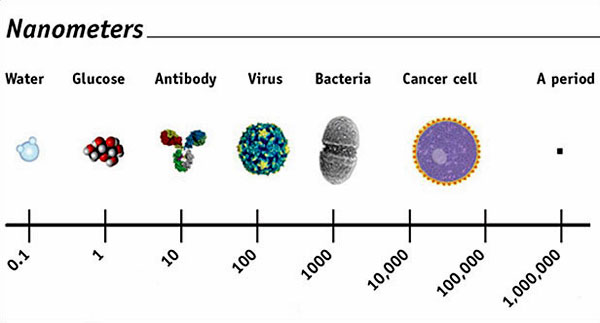

Both the

promise and the potential peril of nanomaterials

come from their staggeringly small size, which is

highlighted by the chart above.

(Note, for

example, how it shows that the periods on this page

are equal to 1 million nanometers.)

Despite the speed bump of the recession,

a global market for nano-containing products that stood at $254

billion in 2005 is projected to grow to $2.5 trillion over the next

four years, says Michael Holman, research director of Boston-based Lux Research.

Another projection, this one from

National Science Foundation senior nanotechnology adviser Mihail

Roco, says that nanotech will create at least 1 million jobs

worldwide by 2015.

By deconstructing and then reassembling atoms into previously

unknown material - the delicate process at the heart of

nanotechnology - scientists have achieved medical advancements that

even staunch critics admit are miraculous. Think of a medical smart

bomb: payloads of cancer-fighting drugs loaded into nanoscale

delivery systems and targeted against a specific tumor.

Carbon nanotubes, rod-shaped and rigid with a strength that

surpasses steel at a mere fraction of the weight, were touted by

commentators at the Vancouver Olympics as helmets, skis and bobsleds

made from nanocomposites flashed by. Those innovations follow

ultralight bicycles used in the Tour de France, longer-lasting

tennis balls, and golf balls touted to fly straighter and roll

farther.

Food scientists, meanwhile, are almost gleeful over the ability to

create nanostructures that can enhance food's flavor, shelf life and

appearance - and to one day potentially use the engineered particles

to craft food without ever involving a farm or ranch.

Yet for all the technology's promise and relentless progress, major

questions remain about nanomaterials' effects on human health.

A

bumper sticker spotted near the sprawling Food and Drug

Administration complex in Rockville, Md., puts it well:

"Nanotech -

wondrous, horrendous, and unknown."

Adds Jim Alwood, nanotechnology coordinator in the

Environmental Protection Agency's Office of Pollution Prevention and

Toxics:

"There is so much uncertainty about

the questions of safety. We can't tell you how safe or unsafe

nanomaterials are. There is just too much that we don't yet

know."

What is known is by turns fascinating

and sobering.

Vial of carbon nanotubes

The

carbon nanotubes in this vial are part of a

booming industry. According to one consulting

firm, the global market for nano-containing

products is projected to grow to $2.5 trillion

by 2014.

Nanoparticles can heal, but they can

also kill.

Thanks to their size, researchers have

found, they can enter the body by almost every pathway. They can be

inhaled, ingested, absorbed through skin and eyes. They can invade

the brain through the olfactory nerves in the nose.

After penetrating the body, nanoparticles can enter cells, move from

organ to organ and even cross the protective blood-brain barrier.

They can also get into the bloodstream, bone marrow, nerves,

ovaries, muscles and lymph nodes.

The toxicity of a specific nanoparticle depends, in part, on its

shape and chemical composition. Many are shaped roughly like a

soccer ball, with multiple panels that can increase reactivity, thus

exacerbating their potential hazards.

Some nanoparticles can cause a condition called oxidative stress,

which can inflame and eventually kill cells.

A potential blessing in controlled

clinical applications, this ability also carries potentially

disastrous consequences.

"Scientists have engineered

nanoparticles to target some types of cancer cells, and this is

truly wonderful," says Dr. Michael Harbut, director of the

Environmental Cancer Initiative at Michigan's Karmanos Cancer

Institute.

"But until we have sufficient

knowledge of, and experience with, this 21st-century version of

the surgical scalpel, we run a very real risk of simultaneously

destroying healthy cells."

When incorporated into food products,

nanomaterials raise other troubling vagaries.

In a report issued in

January, the science committee of the British House of Lords,

following a lengthy review, concluded that there was too little

research looking at the toxicological impact of eating nanomaterials.

The committee recommended that such

"products will simply be denied regulatory approval until further

information is available," and also raised the concern that while

the amount of nanomaterial in food may be small, the particles can

accumulate from repeated consumption.

"It is chronic exposure to nanomaterials that is arguably more

relevant to food science applications," says Bernadene Magnuson, a

food scientist and toxicologist with Cantox Health Sciences

International.

"Prolonged exposure studies must be

conducted."

Given the potential hazards, public

health advocates are calling for greater restraint on the part of

those rushing nano-products to market.

"The danger is there today in the

hundreds of nano-containing consumer products being sold," says

Jennifer Sass, senior scientist and nano expert for the

nonpartisan Natural Resources Defense Council.

"Things that are in the nanoscale

that are intentionally designed to be put into consumer products

should be instantly required to be tested, and until proper risk

assessments are done, they shouldn't be allowed to be sold."

David Hobson, chief scientific officer

for international risk assessment firm nanoTox, adds that the

questions raised by the growing body of research,

"are significant enough that we

should begin to be concerned. We should not wait until we see

visible health effects in humans before we take steps to protect

ourselves or to redesign these particles so that they're safer."

Hobson says that when he talks to

university and industry nano scientists, he sometimes feels as if

he's talking with Marie Curie when she first was playing around with

radium.

"It's an exciting advancement

they're working with," he says. "But no one even thinks that it

could be harmful."

More on Why Size

Matters

At a weeklong Knight Foundation Science Workshop on nanotechnology

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in June, five

professors - four from the Cambridge school and one from Cornell

University - dazzled their fellow participants with extensive

show-and-tells on the amazing innovations coming out of their labs.

At one point, one played a video of a mouse with a severed spine

dragging his lifeless rear legs around his cage.

A scaffolding made

of nanomaterial was later implanted across the mouse's injury.

Further footage showed the same rodent, 100 days later, racing

around his enclosure, all four legs churning like mad.

When the five nanotech pioneers were asked about hazards from the

particles they were creating, only one said she was watching new

health studies closely. The others said size had no impact on risk:

No problems were expected, since the same chemicals they had

nano-ized had been used safely for years.

It's an argument echoed by researchers and nano-manufacturers around

the globe. But those assumptions are challenged by the many research

efforts presenting strong evidence to the contrary, among them

Trouiller's study, which was published in November.

"The difference in size is vital to

understanding the risk from the same chemical," says Schiestl,

who was a co-author on the UCLA study.

"Titanium dioxide is chemically

inert and has been safely used in the body for decades for joint

replacements and other surgical applications. But when the very

same chemical is nanosized, it can cause illness and lead to

death."

Regulators Take a

'Wait-and-See' Approach

Many public health groups and environmental activists fear the

government's lethargy on nanotechnology will be a repeat of earlier

regulatory snafus where deadly errors were made in assessing the

risk of new substances.

"The unsettling track record of

other technological breakthroughs - like asbestos, DDT, PCBs and

radiation - should give regulators pause as they consider the

growing commercial presence of nanotech products," says Patty

Lovera, assistant director of Food & Water Watch.

"This wait-and-see approach puts

consumers and the environment at risk."

While the agency has many critics, the

EPA, for its part, is pursuing an aggressive strategy on

nanotechnology.

Among nano-titanium dioxide's other

uses, the particle is deployed as an agent for removing arsenic from

drinking water, and last year, the EPA handed out 500-page books of

health studies on the particles to a panel of scientists asked to

advise the agency on the possible risk of that practice.

(Another EPA science advisory board held

hearings into the hazards from nanosilver used in hundreds of

products, from pants, socks and underwear to teething rings.)

Dr.

Jesse Goodman, the FDA's chief scientist and

deputy commissioner for science and public

health, says that "there is a most definite

requirement that manufacturers ensure that

the products be safe." But he adds that

compliance is essentially voluntary. The FDA

takes action only after an unsafe product is

reported.

The Food and Drug Administration's

(FDA) handling of nano-titanium dioxide provides a more emblematic example

of the government's overall approach.

Public health advocates and some of the

FDA's own risk assessors are frustrated by what they perceive as the

agency's "don't look, don't tell" philosophy. The FDA doesn't even

make a pretense of evaluating nanoparticles in the thousands of

cosmetics, facial products or food supplements that have already

flooded the market, even those that boast the presence of engineered

particles.

Nano Gold Energizing Cream ($420 a jar)

and Cyclic nano-cleanser ($80 a bar) are among the many similar

products unevaluated by the agency.

Dr. Jesse Goodman, the FDA's chief scientist and deputy

commissioner for science and public health, says the exclusion of

cosmetics and nutritional supplements from its regulations is what

Congress wants.

Goodman adds that,

"there is a most definite

requirement that manufacturers ensure that the products be

safe",

...but says that compliance is

essentially voluntary, with the FDA taking action only after an

unsafe product is reported.

AOL News repeatedly asked what steps the FDA was taking regarding

nano-titanium dioxide, whose risks are acknowledged by other

regulatory bodies, including the EPA and the NIOSH.

The slow-to-arrive answer from

spokeswoman Rita Chappelle:

"If information were to indicate

that additional safety evaluation or other regulatory action is

warranted, we would work with all parties to take the steps

appropriate to ensure the safety of marketed products."

Chappelle says FDA scientists are

conducting research that focuses on nano-titanium dioxide, but

declines to offer any details.

Several of the agency's own safety

experts say they specifically have urged that the engineered

structures not be used in any products they do regulate without

appropriate safety testing.

Why Nano-Optimists

Hold the Upper Hand

Many government investigators join civilian public health

specialists in denouncing the scant money that goes to exploring

nanomaterials' possibly wicked side effects.

The 2011 federal budget proposes

spending $1.8 billion on nanotechnology, but just $117 million, or

6.6 percent, of that total was earmarked for the study of safety

issues.

The Obama administration says it is being appropriately vigilant

about nanotech.

"This administration takes

nanotechnology-related environment, health and safety very

seriously. It is a significant priority," says Travis Earles,

assistant director for nanotechnology in the White House Office

of Science and Technology Policy.

After taking office, he adds,

"We were able to immediately

increase the spending in those areas."

But Earles, in what has become standard

federal practice, is more fixated on nanotech's upsides.

"We are talking about new jobs, new

markets, economic and societal benefits so broad they stretch

the imagination," he says. Yes, "absolutely," there are reasons

for caution, he says.

"But you can't refer to

nanotechnology as a monolithic entity. Risk assessment depends

fundamentally on context - it depends on the specific

application and the specific material."

There's some scientific basis for this

emphasize-the-positive position.

"Every time you find a hazardous

response in a test tube, that should not necessarily be

construed as a guarantee of a real-life adverse outcome," notes

Dr. Andre Nel, chief of the division of nanomedicine at the

California Nanosystems Institute at UCLA.

But there are two ways to proceed in the

face of such uncertainty.

One is to forge ahead, assuming the best

- that this will be one of those times where the lab results don't

correlate to real-world experiences. Another is to hit pause and do

the additional testing necessary to be sure that sickened lab

animals do not portend human harm.

For advocates of more precautions for nanotech, the latter is the

only responsible course.

"From cosmetics to cookware to food,

nanoparticles are making their way into every facet of consumer

life with little to no oversight from government regulators,"

says Lovera from Food & Water Watch.

"There are too many unanswered

questions and common-sense demands that these products be kept

off the market until their safety is assured."

With a moratorium not a realistic

option, the U.S. government, along with its counterparts abroad, is

left to tread gingerly in responding to the emerging evidence of

nanotechnology's potential hazards.

"They don't want to cause either a

collapse in the industry or generate any kind of public backlash

of any sort," says Pat Mooney, executive director of ETC Group,

an international safety and environmental watchdog.

"So they're in the background

talking about how they're going to tweak regulations - where in

fact a lot more than tweaking is required.

"They've got literally thousands of [nano] products in the

marketplace, and they don't have any safety regulations in

place," Mooney continues.

"These are things that we're rubbing

in our skin, spraying in our fields, eating and wearing. And

that's a mistake, and they're trying to figure out what to do

about it all."

Second in a Three-Part

Series

Regulated or Not, Nano-Foods Coming to A Store

Near You

For centuries, it was the cook and the

heat of the fire that cajoled taste, texture, flavor and aroma from

the pot.

Today, that culinary voodoo is being

crafted by white-coated scientists toiling in pristine labs,

rearranging atoms into chemical particles never before seen.

At last year's Institute of Food Technologists international

conference, nanotechnology was the topic that generated the most

buzz among the 14,000 food-scientists, chefs and manufacturers

crammed into an Anaheim, Calif., hall. Though it's a word that has

probably never been printed on any menu, and probably never will,

there was so much interest in the potential uses of nanotechnology

for food that a separate daylong session focused just on that

subject was packed to overflowing.

In one corner of the convention center, a chemist, a flavorist and

two food-marketing specialists clustered around a large chart of the

Periodic Table of Elements (think back to high school science

class).

The food chemist, from China, ran her

hands over the chart, pausing at different chemicals just long

enough to say how a nano-ized version of each would improve existing

flavors or create new ones.

One of the marketing guys questioned what would happen if the

consumer found out.

The flavorist asked whether the Food and Drug Administration would

even allow nanoingredients.

Posed a variation of the latter question, Dr. Jesse Goodman, the

agency's chief scientist and deputy commissioner for science and

public health, gave a revealing answer. He said he wasn't involved

enough with how the FDA was handling nanomaterials in food to

discuss that issue. And the agency wouldn't provide anyone else to

talk about it.

This despite the fact that hundreds of peer-reviewed studies have

shown that nanoparticles pose potential risks to human health - and,

more specifically, that when ingested can cause DNA damage that can

prefigure cancer and heart and brain disease.

Despite

Denials, Nano-Food Is Here

Officially, the FDA says there aren't any nano-containing food

products currently sold in the U.S.

Not true, say some of the agency's own safety experts, pointing to

scientific studies published in food science journals, reports from

foreign safety agencies and discussions in gatherings like the

Institute of Food Technologists conference.

In fact, the arrival of nanomaterial onto the food scene is already

causing some big-chain safety managers to demand greater scrutiny of

what they're being offered, especially with imported food and

beverages.

At a conference in Seattle last year

hosted by leading food safety attorney Bill Marler,

presenters raised the issue of how hard it is for large supermarket

companies to know precisely what they are purchasing, especially

with nanomaterials, because of the volume and variety they deal in.

According to a USDA scientist, some Latin

American packers spray U.S.-bound produce

with a wax-like nanocoating to extend

shelf-life.

"We found no indication that the nanocoating... has ever been tested for

health effects," the researcher says.

Craig Wilson, assistant vice

president for safety for

Costco, says his chain does not test for nanomaterial in the food products it is offered by manufacturers.

But, he adds, Costco is looking,

"far more carefully at everything we

buy... We have to rely on the accuracy of the labels and the

integrity of our vendors. Our buyers know that if they find

nanomaterial or anything else they might consider unsafe, the

vendors either remove it, or we don't buy it."

Another government scientist says

nanoparticles can be found today in produce sections in some large

grocery chains and vegetable wholesalers.

This scientist, a researcher with the

USDA's Agricultural Research Service, was part of a group that

examined Central and South American farms and packers that ship

fruits and vegetables into the U.S. and Canada.

According to the USDA researcher - who

asked that his name not be used because he's not authorized to speak

for the agency - apples, pears, peppers, cucumbers and other fruit

and vegetables are being coated with a thin, wax-like nanocoating to

extend shelf-life.

The edible nanomaterial skin will also

protect the color and flavor of the fruit longer.

"We found no indication that the

nanocoating, which is manufactured in Asia, has ever been tested

for health effects," said the researcher.

A science

committee of the British House of Lords has

found that nanomaterials are already appearing

in numerous products, among them salad dressings

and sauces.

Jaydee Hanson, policy analyst for

the Center for Food Safety, says that they're

also being added to ice cream to make it "look

richer and better textured."

Some foreign governments, apparently

more worried about the influx of nano-related products to their

grocery shelves, are gathering their own research. In January, a

science committee of the British House of Lords issued a lengthy

study on nanotechnology and food.

Scores of scientific groups and consumer

activists and even several international food manufactures told the

committee investigators that engineered particles were already being

sold in,

...to which they're added to ensure easy

pouring.

Other researchers responding to the committee's request for

information talked about hundreds more items that could be in stores

by year's end.

For example, a team in Munich has used nano-nonstick coatings to end

the worldwide frustration of having to endlessly shake an upturned

mustard or ketchup bottle to get at the last bit clinging to the

bottom.

Another person told the investigators

that Nestlé and Unilever have about completed developing a nano-emulsion-based

ice cream that has a lower fat content but retains its texture and

flavor.

The Ultimate

Secret Ingredient

Nearly 20 of the world's largest food manufacturers, among them,

-

Nestlé

-

Hershey

-

Cargill

-

Campbell Soup

-

Sara Lee

-

H.J. Heinz,

...have their own in-house nano-labs, or

have contracted with major universities to do nano-related food

product development.

But they are not eager to broadcast

those efforts.

[UPDATE: Campbell's

spokesman Anthony Sanzio says his company does not have a

nanotechnology program, but adds "We would be irresponsible to

ignore it."]

A team

in Munich, the House of Lords investigators

also learned, is using nano-nonstick

coatings to make it easier to get the last

drops of ketchup out of the bottle.

Kraft was the first major food company

to hoist the banner of nanotechnology.

Spokesman Richard Buino, however,

now says that while,

"we have sponsored nanotech research

at various universities and research institutions in the past,"

Kraft has no labs focusing on it today.

The stance is in stark contrast to the

one Kraft struck in late 2000, when it loudly and repeatedly

proclaimed that it had formed the Nanotek Consortium with engineers,

molecular chemists and physicists from 15 universities in the U.S.

and abroad.

The mission of the team was to show how

nanotechnology would completely revolutionize the food manufacturing

industry, or so said its then-director, Kraft research chemist

Manuel Marquez.

But by the end of 2004, the much-touted operation seemed to vanish.

All mentions of Nanotek Consortium

disappeared from Kraft's news releases and corporate reports.

"We have not nor are we currently

using nanotechnology in our products or packaging," Buino added

in another e-mail.

Industry

Tactics Thwart Risk Awareness

The British government investigation into nanofood strongly

criticized the U.K.'s food industry for,

"failing to be transparent about its

research into the uses of nanotechnologies and nanomaterials."

On this side of the Atlantic, corporate

secrecy isn't a problem, as some FDA officials tell it.

Investigators on Capitol Hill say the FDA's congressional liaisons

have repeatedly assured them - from George W. Bush's administration

through President Barack Obama's first year - that the big U.S. food

companies have been upfront and open about their plans and progress

in using nanomaterial in food.

But FDA and USDA food safety specialists interviewed over the past

three months stressed that based on past performance, industry

cannot be relied on to voluntarily advance safety efforts.

These government scientists, who are actively attempting to evaluate

the risk of introducing nanotechnology to food, say that only a

handful of corporations are candid about what they're doing and

collaborating with the FDA and USDA to help develop regulations that

will both protect the public and permit their products to reach

market.

Most companies, the government

scientists add, submit little or no information unless forced.

Even then, much of the information

crucial to evaluating hazards - such as the chemicals used and

results of company health studies - is withheld, with corporate

lawyers claiming it constitutes confidential business information.

Both regulators and some industry consultants say the evasiveness

from food manufacturers could blow up in their faces.

As precedent, they point to what

happened in the mid-'90s with genetically modified food, the last

major scientific innovation that was, in many cases, force-fed to

consumers.

"There was a lack of transparency on

what companies were doing. So promoting genetically modified

foods was perceived by some of the public as being just

profit-driven," says Professor Rickey Yada of the Department of

Food Science at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada.

"In retrospect, food manufacturers

should have highlighted the benefits that the technology could bring

as well as discussing the potential concerns."

Eating

Nanomaterials Could Increase Underlying Risks

The House of Lords' study identified "severe shortfalls" in research

into the dangers of nanotechnology in food.

Its authors called for funding studies

that address the behavior of nanomaterials within the digestive

system.

Similar recommendations are being made

in the U.S., where the majority of research on nanomaterial focuses

on it entering the body via inhalation and absorption.

The food industry is very competitive, with thin profit margins.

And safety evaluations are very

expensive, notes Bernadene Magnuson, senior scientific and

regulatory consultant with risk-assessment firm Cantox Health

Sciences International.

"You need to be pretty sure you've

got something that's likely to benefit you and your product in

some way before you're going to start launching into safety

evaluations," she explains.

Magnuson believes that additional

studies must be done on chronic exposure to and ingestion of

nanomaterials.

One of the few ingestion studies recently completed was a

two-year-long examination of nano-titanium dioxide at UCLA, which

showed that the compound caused DNA and chromosome damage after lab

animals drank large quantities of the particles in their water.

Meat cooler at grocery store

Sono-Tek, a company based in Milton, N.Y.,

employs nanotechnology in its industrial

sprayers.

"One new application for us is

spraying nanomaterial suspensions onto

biodegradable plastic food wrapping

materials to preserve the freshness of food

products," says its chairman and CEO.

It is widely known that nano-titanium

dioxide is used as filler in hundreds of medicines and cosmetics and

as a blocking agent in sunscreens.

But Jaydee Hanson, policy analyst

for the Center for Food Safety, worries that the danger is greater,

"when the nano-titanium dioxide is

used in food."

Ice cream companies, Hanson says, are

using nanomaterials to make their products "look richer and better

textured."

Bread makers are spraying nanomaterials

on their loaves,

"to make them shinier and help them

keep microbe-free longer."

While AOL News was unable to identify a

company pursuing the latter practice, it did find Sono-Tek of

Milton, N.Y., which uses nanotechnology in its industrial sprayers.

"One new application for us is

spraying nanomaterial suspensions onto biodegradable plastic

food wrapping materials to preserve the freshness of food

products," says Christopher Coccio, chairman and CEO.

He said the development of this nano-wrap

was partially funded by New York State's Energy Research and

Development Authority.

"This is happening," Hanson says.

He calls on the FDA to,

"immediately seek a ban on any

products that contain these nanoparticles, especially those in

products that are likely to be ingested by children."

"The UCLA study means we need to research the health effects of

these products before people get sick, not after," Hanson says.

There is nothing to mandate that such

safety research take place.

The FDA's

Blind Spot

The FDA includes titanium dioxide among the food additives it

classifies under the designation "generally recognized as safe," or

GRAS.

New additives with that label can bypass

extensive and costly health testing that is otherwise required of

items bound for grocery shelves.

A report issued last month by the Government Accountability Office

(GAO) denounced the enormous loophole that the FDA has permitted through

the GRAS classification. And the GAO investigators also echoed the

concerns of consumer and food safety activists who argue that giving nanomaterials the GRAS free pass is perilous.

Food safety agencies in Canada and the European Union require all

ingredients that incorporate engineered nanomaterials to be

submitted to regulators before they can be put on the market, the

GAO noted.

No so with the FDA.

"Because GRAS notification is

voluntary and companies are not required to identify

nanomaterials in their GRAS substances, FDA has no way of

knowing the full extent to which engineered nanomaterials have

entered the U.S. food supply," the GAO told Congress.

Amid that uncertainty, calls for safety

analysis are growing.

"Testing must always be done," says

food regulatory consultant George Burdock, a toxicologist and

the head of the Burdock Group. "Because if it's nanosized, its

chemical properties will most assuredly be different and so

might the biological impact."

Will Consumers

Swallow What Science Serves Up Next?

Interviews with more than a dozen food scientists revealed

strikingly similar predictions on how the food industry will employ

nanoscale technology.

They say firms are creating

nanostructures to enhance flavor, shelf life and appearance. They

even foresee using encapsulated or engineered nanoscale particles to

create foods from scratch.

Experts agreed that the first widespread use of nanotechnology to

hit the U.S. food market would be nanoscale packing materials and

nanosensors for food safety, bacteria detection and traceability.

While acknowledging that many more nano-related food products are on

the way, Magnuson, the industry risk consultant, says the greatest

degree of research right now is directed at food safety and quality.

"Using nanotechnology to improve the

sensitivity and speed of detection of food-borne pathogens in

the food itself or in the supply chain or in the processing

equipment could be lifesaving," she says.

For example, researchers at Clemson

University, according to USDA, have used nanoparticles to identify

campylobacter, a sometimes-lethal food-borne pathogen, in poultry

intestinal tracts prior to processing.

At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, food scientist Julian

McClements and his colleagues have developed time-release

nanolaminated coatings to add bioactive components to food to

enhance delivery of ingredients to help prevent diseases such as

cancer, osteoporosis, heart disease and hypertension.

But if the medical benefits of such an application are something to

cheer, the prospect of eating them in the first place isn't viewed

as enthusiastically.

Advertising and marketing consultants for food and beverage makers

are still apprehensive about a study done two years ago by the

German Federal Institute of Risk Assessment, which commissioned

pollsters to measure public acceptance of nanomaterials in food.

The study showed that only 20 percent of

respondents would buy nanotechnology-enhanced food products.

Third in a Three-Part Series

Obsession With Nanotech Growth Stymies

Regulators

When the United States government

formally acknowledged the world-changing potential of nanotechnology

a decade ago, it was decided that America should lead the way.

Almost immediately, 25 different federal

agencies began scrambling to find uses for the engineered particles

in medicine, energy, transport, weapons, protective devices and

food, as well as thousands more real and dreamed-about applications.

Today, the U.S. is at the fore of worldwide nano-innovation.

But when it comes to regulations and

laws that will protect consumers and workers from the potential

hazards, the country lags badly behind many other nations.

"The government agencies responsible

for protecting the public from the adverse effects of these

technologies seem worn and tattered," former Environmental

Protection Agency assistant administrator Clarence Davies wrote

in a study for the Woodrow Wilson International Center for

Scholars' Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, where he is now

a senior adviser.

Davies, who while at the EPA authored

what became its all-important Toxic Substances Control Act, adds

that the gap between the capabilities of nanotechnology and those of

the regulatory system,

"is likely to widen as the new

technologies advance."

Andrew Maynard in an undated photo

Andrew Maynard, chief science adviser for the

Woodrow Wilson International Center for

Scholars, is among those advocating guidelines

for nano-safety.

"Get these rules wrong - and

we're not sure what they are yet - or ignore

them, and we may cause unnecessary harm to

people and the environment," he says.

Advocates say the importance of

establishing effective nano-safety guidance is difficult to

overstate.

But that effort is also dauntingly

difficult.

"Get these rules wrong - and we're

not sure what they are yet - or ignore them, and we may cause

unnecessary harm to people and the environment," says Andrew

Maynard, chief science adviser for the Wilson Center.

"I don't think it will be the end of

the world as we know it. But it will be a lost opportunity to

get an exciting new technology right."

No One's in

Charge

The U.S. government has no nano czar, no single entity responsible

for setting priorities and doling out billions in research funds.

But on paper, the

National Nanotechnology Initiative

(NNI) comes closest

to fitting that role.

Launched by the Clinton administration's 2001 budget, the NNI was

tasked with coordinating federal investment in nanotechnology

research and development.

The official description of its mission

mandates it to "advance a world-class nanotechnology research and

development program, foster the transfer of new technologies into

products for commercial and public benefit, and support responsible

development of nanotechnology."

While that sounds somewhat czar-like, the reality is that who's in

charge of America's nanotech policy is murky.

"Final authority resides in the

[White House's] Office of Science and Technology Policy, the

Office of Management and Budget, and with the president," says

NNI Director Clayton Teague.

At the same time, Teague's position is

that there's no need for a central, government-wide coordinating

entity on nanotechnology.

"There is no nuclear 'czar,' no

independent authority over information technology, electronic

technology, or biotechnology for health and medicine," he says,

adding that nanotechnology activities "claim less than 1 percent

of the federal research and development budget" and therefore

"simply don't require the special focus you are suggesting."

NNI's biggest shortcoming, say even the

agency's supporters, is its failure to adequately fund basic

research on the safety hazards of nanomaterial.

"The NNI has never effectively

addressed environmental, health and safety issues surrounding

nanotech with a comprehensive, interagency plan," Matthew Nordan,

president of technology forecasting firm Lux Research, told the

Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

Although his statement was made almost

two years ago, committee investigators say there has been little or

no improvement since.

The Obama administration's 2011 budget illustrates the scant federal

resources devoted to nano-safety.

It proposes spending $1.8 billion on

nanotechnology overall, but just $117 million - or 6.6 percent - of

that was earmarked for the study of health-related issues

surrounding the engineered particles.

"It's not a small amount," says

Travis Earles, a nanotech adviser to the White House, defending

the allotment.

Without a single office leading the

charge, the task of guarding against potential nanotech risks falls

to the four agencies most involved in protecting the public, workers

and the environment:

-

the EPA

-

the Food and Drug Administration

-

the U.S. Department of

Agriculture

-

the Occupational Safety Health

Administration

Many of the safety experts in those

agencies told AOL News that the vital regulations for the use,

production, labeling, sale and ultimate disposal of nanomaterial are

not keeping pace with the rush of new products entering the

marketplace.

"Consumers want to know what they

buy, retailers have to know what they sell, and processors and

recyclers need to know what they handle," Christoph Meili, of

the Innovation Society Ltd., said in a report on international

nano regulations funded in part by the Swiss Federal Office for

the Environment.

Some of the scientists involved in

turning nanoparticles into new business opportunities, however,

argue that such protocols would be premature.

"I don't think we have the

scientific basis on which to establish regulations. And I think

that right now a lot of the materials that are being produced

are absolutely benign," says Stacey Harper, assistant professor

of nanotoxicology at Oregon State University.

"The Holy Grail," she says, "is figuring out what are those

[hazardous] features that we need to avoid in engineering these

newer materials."

'Do Nothing to

Prevent Innovation'

The FDA makes stringent demands for safety information on

nanomaterial used in medicine and medical devices, says Jesse

Goodman, its chief scientist and deputy commissioner for science

and public health.

But the agency takes no specific

measures to ensure the safety of the many costly cosmetics and

dietary supplements boasting the benefits of the nanoingredients

they claim to include, even though its own investigators say the

public submits a constant stream of questions and complaints.

"Nanotechnology products present

challenges similar to those the [FDA] faces for products of

other emerging technologies," says an agency press officer, and

"our existing regulations can pretty much handle these

advancements."

FDA headquarters in Rockville, Md.

Getty Images

The FDA

(whose Rockville, Md., headquarters are

shown here) has drawn fire from activists

for its approach to nanomaterials.

The

agency, says the Center for Food Safety's Jaydee Hanson, is "like ostriches with their

heads in the ground, not looking for a

problem so they do not see one."

That stated approach terrifies public

health advocates, as well as some of the agency's own risk

assessors.

"FDA is like ostriches with their

heads in the ground, not looking for a problem so they do not

see one. If they don't see one, they don't have to respond to a

problem," says Jaydee Hanson, senior policy analyst for the

Center for Food Safety.

The FDA does need better tools and

expertise to predict the behavior of nanomaterial, Goodman concedes.

But, he adds,

"to get information needed to assess

the safety of nano-products, we do that in a way that doesn't

cause a problem in terms of preventing innovation."

"Do nothing to prevent innovation" was former Vice President

Dick Cheney's marching orders to the Office of Management and

Budget during President George W. Bush's administration.

"For years OMB acted as industry's

protector," says Celeste Monforton, assistant research professor

at George Washington University's School of Public Health.

She is among the public health activists

who cringe to hear the phrase still being used by President Barack

Obama's regulators.

For all that, however, the FDA appears mostly AWOL in its handling

of nanomaterial in food. Food safety experts in the agency say it is

doing little more than paying bureaucratic lip service to developing

criteria for handling the anticipated avalanche of food, beverages

and related packaging that is heading to store shelves.

(The agency

declined repeated requests to interview any of its food scientists

or regulators.)

With the FDA largely punting, responsibility for ensuring the safety

of the nanomaterial in the marketplace falls to the Consumer Product

Safety Commission - which raises additional problems.

"If you take the nano-products that

we know are out there and divide them up among the safety

agencies, the CPSC is actually responsible for a majority of

those," says David Rejeski, science director for the Technology

Innovation Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center

for Scholars.

In an analysis of CPSC's ability to

handle nanomaterial, Rejeski - who has worked in the White House

Office of Science and Technology Policy - and his team identified

many limitations.

The CPSC has no method of collecting

information on nano-products, and limited ability to inform the

public about health hazards.

"Even if they find a product,"

Rejeski says, "they don't have much ability to do any research

to determine whether it's dangerous."

Finding a Way Around

the Roadblocks

Since 2008, the EPA has been attempting to impose some controls on

carbon nanotubes, whose myriad industrial applications make them one

of the most heavily used engineered particles.

In June, it seemed to have made significant progress toward that

goal, issuing a final notice on a process called "Significant New

Use Rules," which would have required companies to notify the agency

at least 90 days prior to the manufacture, importing or processing

of carbon nanotubes.

The move was cheered by the public health community:

Studies have shown that multiwalled

nanotubes are among the nanomaterials posing potential risks to

humans, capable of damaging or destroying the immune system,

creating asbestos-like lung disease and causing cancer or

mutations in various cells.

The advocates heralded the measure as

the first clear sign that EPA was going to hold nano developers and

users accountable.

Almost immediately, the Washington law firm of Wilmer Hale, while

declining to say whom it represented, threw up procedural

roadblocks, notifying the EPA that it planned,

"to submit adverse and/or critical

comments on behalf of one or more clients."

That was enough to force the EPA to

withdraw the new rules.

The EPA resubmitted its proposal. But on December 1, in an unprecedented

move, the European Commission's Directorate-General for Enterprise

and Industry raised concerns on behalf of a British nanotube maker.

Action on the new rule was put off for another three months, with

the public comment period running through March.

Nevertheless, the EPA believes that by

year's end, its new nanotube requirements will be mandatory.

EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson in December

2009

EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson is pushing

for reforms that would make it mandatory for

companies to report the use of nanomaterials.

Industry players are pushing back.

Efforts such as those undertaken by

Wilmer Hale's client to stall or thwart new or enhanced safety

regulations are legal.

So is another practice used by many

corporations to deny EPA access to health studies and other

information crucial to assessing the risk of a new chemical or

product: declaring that the data is confidential business

information.

EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson has said she wants to put an

end to the corporate maneuvering, especially as it applies to the

new nanomaterial. While testifying before a Senate committee in

December attempting to add teeth to the Toxic Substances Control

Act, Jackson explained the obstacles EPA risk assessors confront in

trying to do their jobs.

Due to the legal and procedural hurdles in the law, over the past 30

years, the administrator said, EPA has only been able to require

testing on about 200 of the more than 80,000 chemicals produced and

used in the United States.

"EPA should have the clear authority

to establish safety standards that reflect the best available

science... without the delays and obstacles currently in place,

or excessive claims of confidential business information,"

Jackson told the lawmakers.

In February, the agency's assistant

inspector general, Wade Najjum, issued a report that said,

"EPA's procedures for handling

confidential business information requests are predisposed to

protect industry information rather than to provide public

access to health and safety studies."

The changes to the Toxic Substances

Control Act that Jackson is advocating would require mandatory

reporting of the use of nanomaterials.

EPA lawyers have told Senate

investigators that the overhaul is vital due to the industry

pressure spawned by the big business opportunities new nano-products

can generate. Meanwhile, some nanotechnology players are pushing

hard to get a resistant EPA to grandfather in nanomaterial already

on the market.

It's a significant point of dispute:

One of the reasons the EPA is

seeking the mandatory reporting requirement in the first place

is that the agency is convinced the current voluntary system of

submitting safety data doesn't work.

In the fall, EPA assistant administrator

Steve Owens told an international conference on regulating

nanomaterial that about 90 percent of the various nanoscale

materials already being used commercially, or thought to be used,

were never reported to the government.

"EPA has determined that regulating

existing nanoscale materials," explains press officer Dale

Kemery, "is needed to ensure protection of human health and the

environment."

A spokesman for the Senate Committee on

Environment and Public Works says two more hearings need to be held

on revising the Toxic Substances Control Act, but they have yet to

be scheduled.

Workers

Require Extra Protections

If there is a front-runner in the effort to institute meaningful

safety regulations for nanomaterial, it is the National Institute

for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the worker safety research arm

of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Physicians and scientists there have

been scrambling to identify the risks that the nanotechnology

industry's employees are encountering on the job.

"Workers and employers can't wait

for us to come up with all the answers before they unleash this

technology. It's unleashed already," says Paul Schulte, manager

of the NIOSH Nanotechnology Research Center.

Having published more than 170

peer-reviewed studies on the health effects from nano exposure, the

agency has established exposure limits for nano-titanium dioxide -

the heavily used material shown to damage and destroy DNA and

chromosomes in studies at UCLA.

The division has recommended that to

ensure safety, the exposure limit for workers handling nano-titanium

dioxide should be 15 times lower than that for the normal size of

the chemical, says Vincent Castranova, the agency's chief of

the Pathology and Physiology Research Branch.

The particles are believed to be used in more than 100 different

manufacturing sites across the country. That's a lot of workers.

NIOSH cannot pass laws, only make recommendations to the

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). And because of all

the tortuous, bureaucratic steps that still must be completed, as

well as the anticipated blocking efforts from some industry

interests, it could be two years before any regulations are

instituted.

OSHA leaders refused to respond to

questions on what the agency will do in the meantime. NIOSH has also

almost completed recommendations for the handling of carbon

nanotubes.

And scientists at NIOSH's animal labs in

Morgantown, W.Va., are now testing the toxicity of almost two dozen

other nanoparticles, including,

-

the diesel additive cerium oxide

-

the metal hardening mixture of

tungsten carbide and cobalt

-

the anti-microbial agent

nanosilver

-

the sunblocker zinc oxide

Vial of nanotubes

Since 2008, the EPA has also been seeking to

impose some controls on carbon nanotubes.

That effort has been made more difficult by

corporate maneuvering.

Most significantly, NIOSH scientists

have identified health risks from nanomaterials not previously

documented by other researchers.

For example, says Castranova, when studying the potential impact of

nano-titanium dioxide exposure on workers' lungs, they also found

cardiovascular effects - damage to the heart muscle.

Separately, the NIOSH team discovered that beyond the

well-documented lung damage that comes from inhalation of carbon

nanotubes, those heavily used carbon structures were causing

inflammation of the brain in the test animals.

"Everything we say could apply to a

consumer. The big difference is that the consumer will likely

see much lower concentrations, for much shorter periods of

time," Castranova says, adding that the findings need to be

viewed with the proper perspective.

Nanomaterials, Castranova says, are not

anthrax, but they aren't Kool-Aid, either.

Other

Countries Exercise Greater Caution

Consumer and safety watchdogs say Canada, the U.K. and the rest of

the European Union are far ahead of the U.S. when it comes to nano

safety requirements.

Canada became the first country to demand stringent reporting

requirements of corporations and universities that import,

manufacture or use more than 2 pounds of nanomaterial a year. The

regulations - necessary for proper risk assessment, the Canadian

government said - were crafted and are enforced by Health Canada and

Environment Canada.

They require the reporting of the

nanomaterial's chemical composition and physical description,

toxicity and proposed use, along with other data.

French lawmakers have drafted legislation with similar stipulations.

And the European Parliament voted last year that its 27 member

states should consider nanomaterials as new substances, and not

cover them under existing laws that do not take into account the

risks associated with the technology.

It also demanded that consumer products

containing nanomaterials be clearly labeled as such, and that the

manufacturers of new cosmetic products containing nanomaterials

provide specific information to regulators six months before the

product is placed on the European market.

In the U.K., the battle cry of nano-regulators is "No data, no

market," especially with food products.

"Products will simply be denied

regulatory approval until further [safety] information is

available," the British House of Lords' science committee said

in December.

It concluded that there was too little

research into the toxicological impact of eating nanomaterials, and

too much secrecy on the part of the food industry.

"It's obvious that in some cases the

U.S. has been a bit lax, though you could make the case that in

some cases the EU requirements are a little bit too stringent,"

says Michael Holman, research director of Lux Research.

"There's no regulatory regime that

can give you 100 percent certainty that everything that comes to

market is going to be perfectly safe."

But to Patty Lovera, assistant

director of Food & Water Watch, that doesn't leave the U.S.

government off the hook.

The failure of the U.S. regulatory

system to keep up with nanotechnology, she states simply,

"puts consumers and the environment

at risk."

|