|

by Larry Brian Radka

from

EinhornPress Website

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Larry Brian Radka

is a retired broadcast engineer, an amateur radio

operator (KB3ZU), and a graduate of the University of

the State of New York. He has written several magazine

articles as well as a few books. Historical Evidence for

Unicorns and Astronomical Revelations or 666 were

published in the mid 1990's and his latest release, in

2006, is The Electric Mirror on the Pharos Lighthouse

and Other Ancient Lighting. It may be ordered by

clicking:

http://einhornpress.com/mirror.aspx.

(A similar article by

Larry appeared in David Hatcher Childress's World

Explorer magazine recently) |

"Electric batteries, 2000 years ago!!! Surprised? No need to be,

really," declared Willard F. M. Gray, an electrical

engineer for General Electric.

"There were some pretty smart metal

workers in the ancient city of Baghdad, Persia [now Iraq]. They

did a lot of fine work in steel, gold, and silver. You may

wonder what this had to do with electric batteries. It seems

that copper vases, some of whose ages go back 4000 years, were

unearthed several years ago which had designs plated on them in

gold or silver, even some were plated with antimony."

In his editorial titled "A Shocking

Discovery," in a 1963 edition of the prestigious Journal of the

Electrochemical Society, he also added:

"Occasionally, we feel a bit smug

about our tremendous advances in the nuclear science and the

like, but when we are scooped by some ancient metal smiths we

are most assuredly brought down to earth and humbled. It will

ever be so." [i]

These so-called Baghdad batteries,

discovered in the 1930's, are now old news, and the evidence that

the ancients used them to electroplate some of the artifacts stored

in museums around the world is likewise common knowledge.

Nevertheless, for readers who are not

familiar with the discovery of these ancient electric cells, we will

call on the German rocket scientist Willy Ley to update us.

In a 1939 article in Astounding

magazine, he wrote:

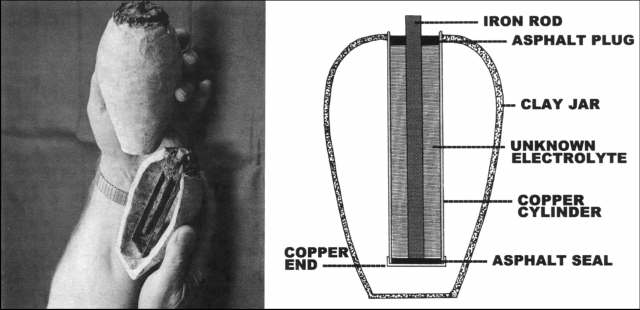

"Dr. Wilhelm Koenig of the

Iraq Museum in Bagdad reported recently that a peculiar

instrument was unearthed by an expedition of his museum in the

summer of 1936. The find was made at Khujut Rabu'a, not far to

the southeast of Bagdad. It consisted of a vase made of clay,

about 14 centimeters high and with its largest diameter 8

centimeters.

The circular opening at the top of

the vase had a diameter of 33 millimeters. Inside of this vase a

cylinder made of sheet copper of high purity was found - the

cylinder being 10 centimeters high and having a diameter of

about 26 millimeters, almost exactly 1 inch.

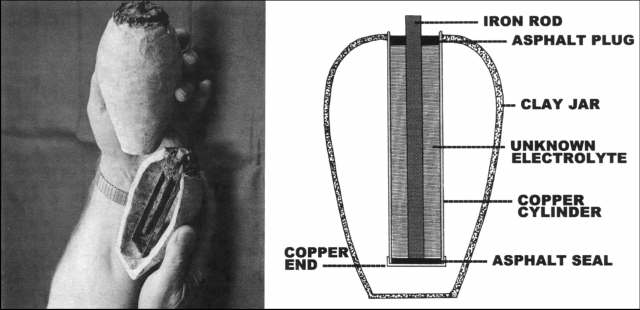

A replica and

diagram of one of the ancient electric cells (batteries) found

near Bagdad

"The lower end of the copper

cylinder was covered with a piece of sheet copper, the same

thickness and quality as the cylinder itself.

The inner surface

of this round copper sheet - the one that formed the inner bottom

of the hollow cylinder - was covered with a layer of asphalt, 3

millimeters in thickness. A thick, heavy plug of the same

material was forced into the upper end of the cylinder.

The center of the plug was formed by

a solid piece of iron - now 75 millimeters long and originally a

centimeter or so in diameter. The upper part of the iron rod

shows that it was at first round, and while the lower end has

partly corroded away so that the rod is pointed now at the lower

end, it might be safely assumed that in the beginning it was of

uniform thickness.

"An assembly of this kind cannot very well have any other

purpose than that of generating a weak electric current. If one

remembers that it was found among undisturbed relics of the

Parthian Kingdom - which existed from 250 B.C. to 224 A.D. - one

naturally feels very reluctant to accept such an explanation,

but there is really no alternative.

The value of this discovery

increases when one knows that four similar clay vases were found

near Tel'Omar or Seleukia - three of them containing copper

cylinders similar to the one found at Khujut Rabu'a. The

Seleukia finds were, apparently, less well preserved - there are

no iron rods in evidence any more. But close to those four vases

pieces of thinner iron and copper rods were found which might be

assumed to have been used as conductive wires.

"Similar 'batteries' were also found in the vicinity of Bagdad

in the ruins of a somewhat younger period. An expedition headed

by Professor Dr. E. Kühnel, who is now director of the

Staatliches Museum in Berlin, discovered very similar vases

with copper and iron parts, at Ktesiphon - not far from Bagdad.

These finds date from the time when the dynasty of the

Sassanides ruled Persia and the neighboring countries - 224

A.D. - 651 A.D.

"While the probable date of the invention is entirely open to

conjecture, it seems likely that it was made in or near Bagdad,

since all known finds were made in the vicinity of this city. It

must be assumed, of course, that the subjects of the Sassanides

had some use for them, and Dr. Koenig, the discoverer of the

best preserved of all these vases, suggests that this use might

still be in evidence in Bagdad itself.

He found that the silversmiths of

Bagdad use a primitive method of electroplating their wares. The

origin of their method cannot be ascertained and seems to date

back a number of years. Since galvanic batteries of the type

found would generate a sufficiently powerful current for

electrogilding small articles fashioned of silver, it might very

well be that the origin of the method has to be sought in

antiquity." [ii]

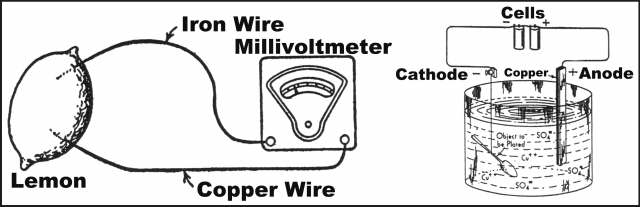

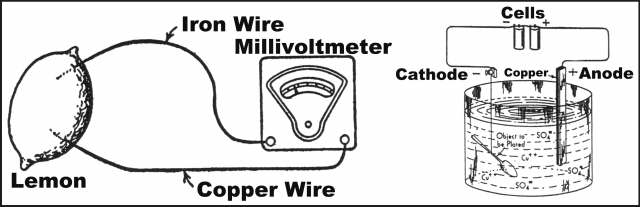

Click above image

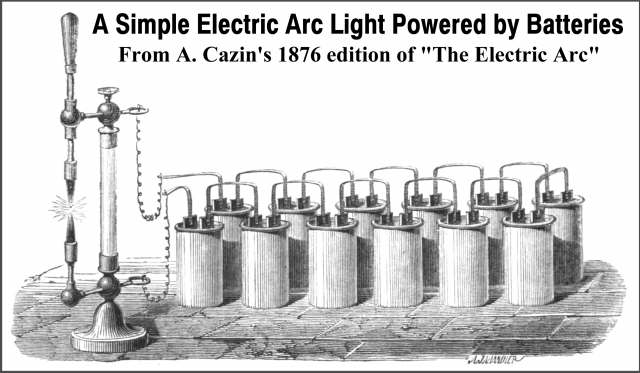

A Simple low-voltage

electric cell and a simple electroplating bath and procedure

Electrogilding or electroplating

basically only requires rods or wire, a couple of simple electric

cells (batteries) connected to a bath of common chemicals wherein

the items to be electroplated are placed.

However, beside the materials already

mentioned, using glass, lead, zinc, and some types of electrolytes

like caustic soda and sulfuric acid produce stronger types of

non-rechargeable Bagdad-types of primary batteries - as well as

powerful rechargeable storage or secondary batteries that could have

been used for ancient electric lighting.

The ancients had access to all of these materials:

-

Bronze Age people made

glass around 3,000 B.C., and the Egyptians manufactured

glass beads about 2,500 B.C. Later, Alexandrians

manufactured modern types of glass, during the Ptolemaic

period - when the Pharos Lighthouse rose up.

-

Prehistoric man smelted

Lead. One old piece of lead work in the British Museum dates

back to 3,800 B.C. Several millenniums later, Romans were

using it at length in their cooking pots, tankards, and

plumbing; and many probably poisoned their brains in the

process. The resulting insanity may have eventually

contributed to the fall of the empire.

With regards to ancient zinc, Rene

Noorbergen, pointed out:

"In 1968, Dr. Koriun Megurtchian

of the Soviet Union unearthed what is considered to be the

oldest large-scale metallurgical factory in the world at

Medzamor, in Soviet Armenia. Here, 4,500 years ago, an unknown

prehistoric people worked with over 200 furnaces, producing an

assortment of vases, knives, spearheads, rings, bracelets, etc.

The Medzamor craftsmen wore

mouth-filters and gloves while they labored and fashioned their

wares of copper, lead, zinc, iron, gold, tin, manganese and

fourteen kinds of bronze. The smelters also produced an

assortment of metallic paints, ceramics and glass."

[iii]

In the course of the excavation of the

Agora in Athens, a roll of sheet zinc, 98% pure, was supposedly

found in a sealed deposit dating from the 3rd or 2nd century B.C.

Fragments of a zinc coffin was reported to have fairly recently been

discovered in Israel, which, judging by an artifact found nearby,

dates back to 50 B.C.

Caustic soda and lye are synonymous.

"Clothes were cleansed in

antiquity," according to Charles Singer, by "lye from

natron or wood-ash," [iv]

so it was available for use as an electrolyte to activate

powerful electric cells in antiquity.

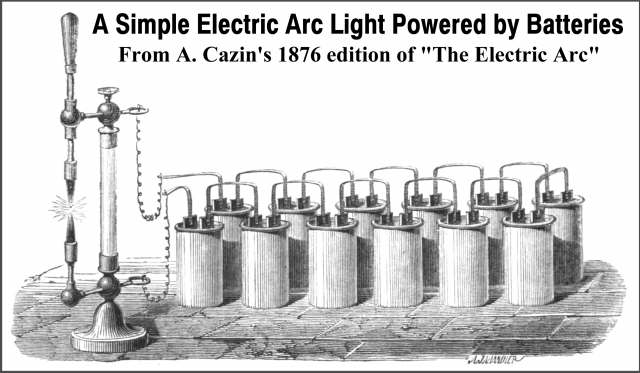

A carbon arc light

popular in the 19th century, illustrated in the issue 1875 issue

above

Manmade sulfuric acid (sulphuric

acid) has been around at least since the seventh century B.C., and

natural sulfuric acid has been available to use as an electrolyte

for countless years before then.

An article in Harper's New

Monthly Magazine, under the title of "Secretion of Sulfuric Acid

by Mollusks," points to where both modern and ancient man could have

obtained natural sulfuric acid.

This quaint publication, which often

serves as an excellent source of rare historical information,

related:

"The remarkable fact was announced

some years ago that certain gastropod mollusca secrete

free sulfuric acid; and this has since then been not

infrequently observed in the case of the gigantic Dolium

galea, which discharges from its proboscis a drop of liquid

or saliva that produces a very sensible effervescence on chalk

or marble.

This secretion from different

mollusca, carefully analyzed, showed a considerable percentage

of free sulphuric acid, some of combined sulphuric acid,

combined chlorohydric acid, with potassa, soda, magnesia, and

other substances; the glands secreting the liquids constituting

from 7 to 9 per cent of the total weight of the animal. With

this acid secretion there is, at least in some species, an

evolution of pure carbonic gas, one gland, weighing

approximately about 700 grains, yielding 206 cubic centimeters.

The genera so far known to furnish

this secretion are Dolium, Cassis, Tritonium, Cassidaria,

Pleurobranchidium, Pleurobranchus, and Doris. The precise object

of this secretion is not entirely understood, although it is

suggested that it is used in perforating the bivalve shells or

other mollusca which serve as article of food."

[v]

However, the ancients probably did not

need to rely on any natural source of sulfuric acid for the

electrolyte in their batteries.

They likely, as today, relied on

their ingenuity to manufacture their own.

Speaking of the ancient Assyrians (of

Iraq) and the chemicals they produced by 650 B.C., in a paper read

before the Society for the Study of Alchemy and Early Chemistry,

Doctor Reginald Campbell Thompson, the author of A

Dictionary of Assyrian Chemistry and Geology, informs us that:

"The sources from which our

knowledge of Assyrian Chemistry is obtained are a very small

part of the collections of cuneiform tablets in our museums,

which may perhaps be reckoned at a quarter of a million roughly

in number, and of this chemistry, almost all our knowledge comes

from tablets of the Seventh Century B.C.

But that the ancient Sumerians had a

very practical knowledge of chemical methods even before the

invention of writing, let us say, very early in the Fourth

Millennium B.C., is to be inferred from the beautiful gold work

found by Sir Leonard Wooley at Ur, and the copper and

bronze castings found throughout Southern Mesopotamia.

The written word, however, of their

methods has survived only sparsely by comparison, this being due

to three causes: first, the illiteracy of the craftsmen;

secondly, the habit of all Guilds to conceal their methods by

the use of cryptic expressions; and thirdly, the close guarding

of secrets, which were frequently handed down from father to son

by word of mouth.

A Sargon II

(722-705 BC) era glass jug and first century transparent glass

vase

"In the Seventeenth Century B.C. we

have a text of outstanding importance for the history of

Chemistry in a tablet written by a glass-maker. Later on, in the

Seventh Century, we have a collection of glass recipes made at

the instance of King Ashurbanipal (668 - 626 B.C.).

More generally we have a large

collection of medical texts which allow us to identify numerous

substances in use during the First Millennium B.C. Finally I

must mention numerous Sumero-Assyrian dictionaries which give

lists of chemical words, also dating from the same period.

"By 650 B.C. the list of chemicals may be said to include Common

Salt, Sal gemma, red Sal Gemma, Lime, Saltpeter from the earth,

Carbonate of Soda from the walls, Nitrate of Potash from walls,

Sal Ammoniac from plants, Gypsum, Mercury from cinnabar, Alum,

Black and Yellow Sulphur, Bitumen, various forms of Arsenic, red

and black Copper Oxide, Chrysocolla, Haematite, Magnetic Iron

Ore, Iron Pyrites (which leads to Vitriols), Iron Sulphide,

Copper Sulphate; and if I am right, they had a word hannabahru

for the fuming sulphuric acid from Green Vitriol."

[vi]

Now that we have established that the

ancients also possessed all of these chemicals, including Sal

Ammoniac and sulphuric acid, which are excellent

battery-making materials, we need to look at least one example of a

primary and second type of powerful battery that they could have

easily produced to energize their ancient electric lights.

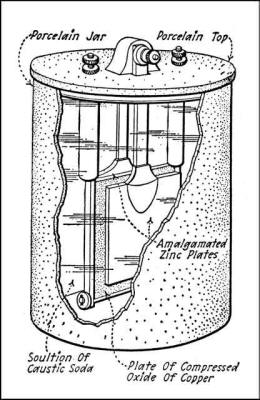

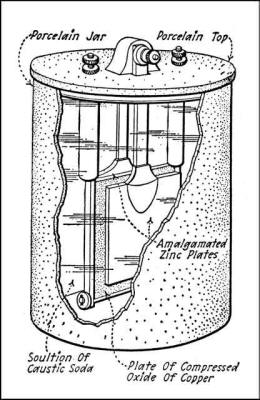

One example of a powerful primary battery that the ancients could

have manufactured, using caustic soda or some equivalent, is the

Lalande Battery.

Felix Lalande and Georges

Chaperon used a similar electrolyte to produce their primary

battery in the nineteenth century, and it supplied enough current to

power electric railroad lights for many days before it needed to be

restored. Likewise, several large Lalande cells placed in series and

parallel could have supplied enough voltage and current to power

bright lights in antiquity for a long time before any of the

battery's elements would have needed replacing.

This type of battery needs no external

source of electricity to revitalize it. After it has discharged,

replacing some of its internal ingredients restores the unit to full

capacity.

In an Encyclopaedia Britannica

article published in 1929, G. W. Heise, a research chemist at

the National Carbon Company of Cleveland, Ohio, and an author

of numerous articles in technical journals, explained the

"heavy-duty characteristics" of this primary battery - which would

certainly qualify it for carbon arc light usage in the searchlight

on the ancient Pharos Lighthouse.

An animated

illustration of a simple battery powered searchlight or electric

mirror

He maintained:

"The Lalande cell is one of the most

efficient and satisfactory primary batteries known today for the

special classes of service to which it is suited. It lends

itself readily to rugged construction; it is relatively cheap to

make and operate; it is very reliable in its action and has a

high current output per unit of volume (about 1 ampere hour per

8 cc. of electrolyte). The cell is made in units as large as 500

to 1,000 ampere hour sizes.

Because it requires no attention for

long periods of time and because of its excellent continuous

discharge and heavy-duty characteristics, the Lalande cell is at

present much used in railway signal operation. It can be made in

dry or non-spillable form either by gelatinizing the caustic

soda solution with small quantities of starch or by using such

expedients as making a paste out of electrolyte and magnesium

oxide.

An Edison or

Lalande battery, a powerful primary electric cell

"Air cells of the Lalande type, in

which a porous carbon accessible to air is substituted for the

usual copper oxide element, are also feasible. These have an

even more horizontal discharge curve than the copper oxide cell,

since the potential of the cathode remains virtually unchanged

during service life.

The caustic soda air cell has an

open circuit voltage of 1.35 to 1.45 and an operating voltage

even on comparatively heavy drains above 1.0 volt - perhaps 0.4

to 0.5 volt higher than that of a standard copper oxide cell.

The carbon electrode can be used repeatedly, only zinc and

electrolyte requiring renewal each time the cell is completely

discharged." [vii]

An animated picture

of the Pharos Lighthouse

A railroad signal light sending

directions down the track, like the Pharos flashed it messages over

the sea, certainly demanded their periodic renewal, but eventually a

more practical and economical source of illuminating power, the

lead-acid secondary storage battery took its place.

This powerhouse is easy to build, by

immersing two lead plates in a solution of sulfuric acid in a glass

container, all of which the ancients possessed. However, before a

simple storage cell will produce electric current, it needs charged.

To initially energize it, you need only to connect it to a source of

direct current, like a primary battery or thermocouple.

We already know the ancients manufactured primary cells, like the

Baghdad batteries, that serve the purpose, but they could have

easily used a thermo-electric generator, which is a simple device to

make.

They merely had to heat one of two

dissimilar metallic conductors joined together, like copper and

iron, to create a thermo-electric generator, which is also called a

thermopile and thermo-electric stove.

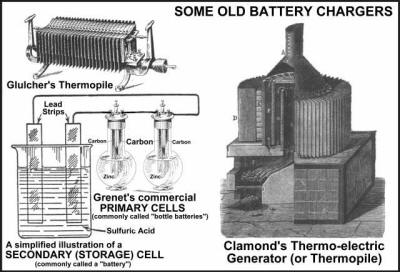

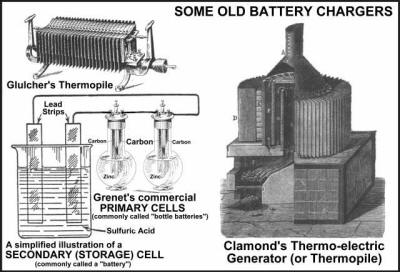

The Gülcher Thermopile, being

more convenient, less costly, and cleaner than primary batteries,

was a popular means of charging storage batteries in the nineteenth

century.

It gave on a short circuit about 5

amperes of current at 4 volts. However, this thermo-electric

generator hardly compared to the power output of the improved

Clamond Thermopile of 1879, which produced 109 volts, with an

internal resistance of 15.5 ohms.

It could easily illuminate bright

electric lights and also deliver a lethal dose of energy! In 1893,

Dr. Giraud's Thermo-electric stove, 3 feet high and 20 inches in

diameter and fired by coal, not only could charge batteries but

could also light several electric lamps, as well as heat a room 21

feet square. It was an expensive unit to build but cost would have

been no obstacle for a wealthy ruler of any ancient city like

Alexandria.

The ancient Greek kings ruling that city

may well have relied on similar types of thermopiles to charge

powerful lead-acid batteries hooked to the arc light on the Pharos

lighthouse, an essential element for shipping safety and the city's

commercial survival.

Lead-acid storage cells will produce a voltage of about 2 volts

each, and the ancients could have easily connected several of them

in series and parallel to create a powerful battery. Hooking its

poles up to a couple of chunks of carbon from the remnants of a wood

fire, touching the two together, and separating them a certain short

distance will ignite a brilliant arc of light.

That is child's play. And it would not

have taken long for them to realize that maintaining that distance

will sustain a brilliant carbon arc light - the kind that would

eventually be reflected from the huge mirror on the Pharos

Lighthouse.

Sound likely?

It certainly does, and even more so if

we consider what some renowned Egyptologists observed and some of

the astonishing ancient lighting testimony that cannot be easily

explained otherwise.

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1798 - 1875), a distinguished

nineteenth-century Egyptologist, pointed out that the ancient

Egyptian,

"paintings offer few representations

of lamps, torches, or any other kind of light."

[viii]

How could this be - when the ancient

Egyptians emblazoned on their monuments almost every other important

innovation that shaped their daily lives? Perhaps, like a more

contemporary authority, Robert Temple,

[ix] observed, concerning all the previously

unrecognized ancient lenses stashed away in the world's museums, the

answer lies in the fact that people are not looking for ancient

electric lights so they simply do not recognize them.

Wilkinson's observation reminds us of what the prominent astronomer

Sir J. Norman Lockyer, who also studied ancient Egyptian

temples and tombs in depth, noticed in 1894.

In his Dawn of Astronomy, he

brought attention to an enigma, at the time, when he pointed out:

"In all freshly-opened tombs there

are no traces whatever of any kind of combustion having taken

place, even in the inner-most recesses. So strikingly evident is

this that my friend M. Bouriant, while we were discussing this

matter at Thebes, laughingly suggested the possibility that the

electric light was known to the ancient Egyptians."

[x]

Carbon arc

searchlights in a Denderah temple crypt

The extensive proofs provided in The

Electric Mirror on the Pharos Lighthouse and Other Ancient Lighting

[xi] clearly demonstrate

that "possibility."

This work also includes excellent

reproductions of the extraordinary ancient illustrations discovered

on the crypt walls beneath the

Temple of Hathor (Isis) at Denderah.

They seem to clearly portray electric carbon arc searchlights and

filament bulbs. Priests apparently used them to illuminate the

temple as well as various tombs - and more importantly, the mighty

Pharos Lighthouse. So M. Bouriant's casual suggestion

that the ancient Egyptians may have employed electric lights is no

longer a laughing matter.

With reference to the remarkable cleanliness of one particular

ancient Egyptian tomb, Dr. F. L. Griffith, Professor of

Egyptology at the University of Oxford, in an article entitled

"The Religious Revolution in Egypt," wrote:

"There are few examples of rock

architecture in Egypt more pleasing than this admirably

proportioned, spotlessly white sepulcher of one who as governor

of Akhenaton ranked as head of the notables. It is cut in the

limestone cliffs that form a semicircle round the plain of Tell

el-Amarna." [xii]

Deep, dark tombs like this one would

have required an electric light to illuminate them enough for

ancient artisans to have embellished their walls with the correctly

colored and finely detailed images of the deceased's life.

They

could never have succeeded with the light from dim candles, sloppy

oil lamps, or smoky torches that would have starved them of

essential oxygen and left unsightly soot marks clinging all over the

tomb walls and ceilings.

Several writers have suggested that the ancient Egyptians

illuminated their tombs by reflecting rays of sunlight with an

arrangement of mirrors.

However, light-absorbing mirrors are not

a good option for pressing and complex projects demanding more than

the Sun's periodic appearance - in cloudless, dust-free, daylight

skies.

Beside this, the maze of rooms in some

tombs would have caused insurmountable problems for technicians

trying to keep a large number of mirrors critically aligned and

continuously tracking one another as they tried to catch and bounce

around the diminishing rays of our elusive sun. Moreover, some

technician or artisan confined in a complex Egyptian tomb would have

eventually stepped in front of one of the reflectors and have broken

a critical link in the intricate chain of light - abruptly leaving

others down the line struggling in total darkness.

Furthermore, artisans using oil-fired lights could have never

completely removed the soot from the ceilings and walls after

finishing their tasks because they would have had to clean up the

smudge with the same smoke-belching lights that produced it. So how

else, other than with the use of clean-burning electric lamps, could

they have managed to meticulously decorate about 400 underground

grave systems with no trace of any smoke residue?

Of course, some tombs now show soot

marks left from the oil lights of grave robbers who had previously

violated them - but Lockyer spoke of "freshly-opened tombs."

Beside all this common sense that strongly supports the need for

ancient electric lighting stands several outstanding examples of

ancient testimony that cannot be reasonably explained in any other

way.

An animated photo of

ancient electric lights in a Denderah crypt

In the second century, a Syrian temple

sheltered a statue of a goddess with one of these types of lights

mounted on her head.

Writing at the time, Lucian of

Samosata on the Euphrates says:

"She bears on her head a stone

called a 'lamp,' and it receives its name from its function.

That stone shines in the night with great clarity and provides

the whole temple with light, as with [oil] lamps. In the

daytime, it shines dimly, but has a very fiery aspect."

[xiii]

Carbon arc lights

hanging in a 19th-century French Hotel

This obviously seems like some type of

electric light since Lucian clearly called the stone a "lamp" - and it

was powerful enough to light up the whole temple. Furthermore, an

electric light, any type for that matter, typically shines brightly

at night and very dimly in the daytime.

However, since Lucian called the

lamp a "stone," perhaps it was the only way he knew how to describe

carbon, the carbon of a simple electric arc lamp.

And, since he said it had a "very fiery

aspect" in the daytime, this makes us think that it might have been

some kind of fiery carbon arc light - like those used to illuminate

nineteenth-century cities and to power searchlights.

St. Augustine's demon

arc light

A couple of centuries later, in his

City of God, St. Augustine (354 - 430 A.D.) pointed out that in

Egypt,

"There was, and still is, a temple

of Venus, in which a lamp burns so strongly in the open air that

no storm or rain extinguishes it."

He blamed "the reality" of this

marvelous lamp, likely an electric arc light, on the miracles of the

"black arts" performed by demons and men [the illuminati].

He also wrote:

"We add to that inextinguishable

lamp a host of other marvels of human and of magical origin - that

is miracles of the demon's black arts performed by men, and

miracles performed by the demons themselves. If we choose to

deny the reality of these, we shall ourselves be in conflict

with the truth of the sacred books in which we believe.

Thus, either human ingenuity has

devised in that inextinguishable lamp some contrivance based on

the asbestos stone or else it was contrived by magic art to give

men something to marvel at in that shrine; or perhaps some demon

presented himself there under the name of Venus with which such

effect that this prodigy was displayed to the public there and

continued there for so many years."

[xiv]

An arc light from the

collection of Larry Brian Radka

This church father also claimed

that the,

"asbestos stone, which has no fire

of its own, and yet, when it has received fire, blazes so

fiercely with a fire not its own that it cannot be quenched."

This points to the carbon in an arc

light receiving its fire from an electric source - an ancient

battery - "not its own."

"It is quite

independent of the action of the air."

Furthermore, he also claimed "no

storm or rain extinguishes it."

This also points to the electric arc

light because Chamber's Encyclopaedia maintains that it,

"can be produced in a vacuum, and

below the surface of water, oils, and other non-conducting

liquids, and it is thus quite independent of the action of the

air." [xv]

Carbon arc

searchlights beaming out of the Electric Building at Chicago's 1893

Exposition

A couple of hundred years later,

carbon arc light technology still survived.

Electric

searchlights nightly lit up Jerusalem then, and a substantial

portion of it at that, by casting their beams a great distance from

another holy edifice - the circular Church of the Ascension on

the Mount of Olives.

Arculf (Arculfus), a Frankish

bishop, perhaps of Périgueux, who visited and explored the Holy

Land, accompanied by Peter, a Bergundian monk, who acted as a guide,

reported the details and effects of eight brilliant lights - and some

others also.

The Catholic Encyclopedia

[xvi] gives us a little

background on his marvelous report - as follows:

"St. Bede relates (Hist. Eccles.

Angl., V, 15) that Arculf, on his return from a pilgrimage to

the Holy Land about 670 or 690, was cast by tempest on the shore

of Scotland.

He was hospitably received by

Adamnan, the abbot of the island monastery of Iona, to whom he

gave a detailed narrative of his travels to the Holy Land, with

specifications and designs of the sanctuaries so precise that

Adamnan, with aid from some extraneous sources, was able to

produce a descriptive work in three books, dealing with

Jerusalem, Bethlehem, the principal towns of Palestine, and

Constantinople.

Adamnan presented a copy of this

work to Aldfrith, King of Northumbria in 698. It aims at

giving a faithful account of what Arculf actually saw during his

journey. As the latter 'joined the zeal of an antiquarian to the

devotion of a pilgrim during his nine months' stay in the Holy

City, the work contains many curious details that might

otherwise have never been chronicled.'"

The following two excerpts, from The

Pilgrimage of Arculfus in the Holy Land (About the Year A.D.

670) was translated by the Rev. James R. MacPherson in 1895.

He says:

"The translation has been made as

literal as possible in passages where the exact rendering was of

any controversial or archaeological importance, as in the

description of the sites and buildings."

Here are those excerpts, describing one

of the buildings and the effects of its bright electric

searchlights:

"In the western side of the church

we have mentioned above [before], twice four windows have been

formed high up with glazed shutters, and in these windows there

burn as many lamps placed opposite them, within and close to

them. These lamps hang in chains, and are so placed that each

lamp may hang neither higher nor lower, but may be seen, as it

were, fixed to its own window, opposite and close to which it is

specially seen.

The brightness of these lamps is so

great that, as their light is copiously poured through the glass

from the summit of the Mountain of Olivet, not only is the part

of the mountain nearest the round basilica to the west

illuminated, but also the lofty path which rises by steps up to

the city of Jerusalem from the Valley of Josaphat is clearly

illuminated in a wonderful manner, even on dark nights; while

the greater part of the city that lies nearest at hand on the

opposite side is similarly illuminated by the same brightness.

The effect of this brilliant and

admirable coruscation of the eight great lamps shining by night

from the holy mountain and from the site of the Lord's

ascension, as Arculf related, is to pour into the hearts of the

believing onlookers a greater eagerness of the Divine love, and

to strike the mind with a certain fear along with vast inward

compunction."

"This also we learned from the narrative of the sainted Arculf:

That in that round church, besides the usual light, of the eight

lamps mentioned above as shining within the church by night,

there are usually added on the night of the Lord's Ascension

almost innumerable other lamps, which by their terrible and

admirable brightness, poured abundantly through the glass of the

windows, not only illuminate the Mount of Olivet, but make it

seem to be wholly on fire; while the whole city and the places

in the neighborhood are also lit up."

[xvii]

Ancient candles and oil lamps could

never have begun to light up a "whole city" a mile away, but

Arculf's electric mirrors (searchlights), as described above, were

quite adequate.

However, the wily priests maintaining

the bright lamps in ancient lighthouses, temples, and tombs kept

their searchlight technology a secret because they needed to inspire

their naïve flocks to revere their religion. Yet, they could not

resist bragging to succeeding generations of illuminati - by cleverly

emblazoning their electrical wisdom on their monuments.

Unfortunately, until relatively

recently, not many people have taken seriously the ancient

electric lighting testimony left to us - although the proof and

techniques have stood out in front of our eyes for thousands of

years now. The ancient electrical wizards must be disgusted with

their failure to induce productive observation in modern

generations, or perhaps they are laughing loudly somewhere at our

blind wisdom of the past instead.

What electrical truth Edison and others stumbled onto in the

nineteenth century is merely old wine poured into a new bottle,

and the bible verifies this by maintaining that there is nothing new

under the sun. Yet, our pride often seems to stand in the way of

accepting the fact.

However, one wise writer set this human weakness aside and boldly

admitted the truth - over a century ago!

"Whenever, in the pride of some new

discovery, we throw a look into the past, we find, to our

dismay, certain vestiges which indicate the possibility, if not

the certainty, that the alleged discovery was not totally

unknown to the ancients," wrote Madame H. P. Blavatsky,

in Isis Unveiled.

"It is generally asserted that

neither the early inhabitants of the Mosaic times, nor even the

more civilized nations of the Ptolemaic period were acquainted

with electricity. If we remain undisturbed in this opinion, it

is not for the lack of proofs to the contrary."

[xviii]

REFERENCES

[i] "A Shocking Discovery,"

Journal of the Electrochemical Society, September 1963, Vol.

110 No. 9

[ii] Under SCIENCE ARTICLES in the March 1939 issue of

ASTOUNDING magazine, Willy Ley's article was listed on the

contents page as "ELECTRIC BATTERIES - 2,000 YEARS AGO! SO

YOU THOUGHT OUR CIVILIZATION FIRST DISCOVERED ELECTRICITY?"

[iii] Secrets of the Lost Races, New Discoveries of Advanced

Technology in Ancient Civilizations, New York 1977

[iv] A History of Technology, Volume II, London 1956

[v] Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. CCXLVI, November

1870, Volume XLI

[vi] "A Survey of the Chemistry of Assyria in the Seventh

Century B.C.," Ambix, Vol. II, No. 1, June 1938

[vii] Encyclopaedia Britannica, 14th Edition, Article: "Battery

- Lalande Cell," London 1929

[viii] A Popular Account of the Ancient Egyptians, New York

1988

[ix] In The Crystal Sun, Rediscovering a Lost Technology of

the Ancient World, London 2000

[x] The Dawn of Astronomy, M.I.T. Press, Cambridge 1964 (a

reprint of Lockyer's 1894 first edition)

[xi] Published by The Einhorn Press, Parkersburg, West

Virginia in 2006 and edited by the author of this article

[xii] J. A. Hammerton's Universal World History, Volume II,

New York 1937

[xiii] Lucian, Loeb Classical Library, Volume IV, New York

1925

[xiv] Concerning the City of God Against the Pagans,

numerous editions are available

[xv] Chamber's Encyclopaedia, A Dictionary of Universe

Knowledge for the People, New York 1890

[xvi] The Catholic Encyclopedia, in 15 volumes, New York

1907

[xvii] The Library of the Palestine Pilgrim' Text Society,

Volume III, London 1894

[xviii] Isis Unveiled, A Master Key to the Mysteries of

Ancient and Modern Science and Theology, New York 1877

|