|

by Lumir G. Janku 1996 from AnomaliesAndEnigmasLibrary Website

The Coso Artifact

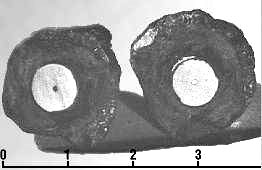

They found a fossil-encrusted geode on

February 13, 1961, on a mountain peak 4,300 feet high, about 340

feet above the dry Owens Lake, six miles northeast of Olancha.

Geologists estimate that about 10,000 years ago, Owens Lake was

as high as the top of the peak.

Enclosing the core was what appeared to be a ceramic collar that was itself encased in a hexagonal sleeve carved out of wood that had, presumably at a later date, become petrified. Around the petrified wooden enclosure was the outer layer of the geode, consisting of hardened clay, pebbles, bits of fossil shell, and two nonmagnetic metallic objects resembling a nail and a washer.

A fragment of copper still remaining between the ceramic and the petrified wood suggests that the two may once have been separated by a now decomposed copper sleeve. Later, the x-ray of the object would reveal a shape resembling a spark plug, according to the editor of INFO Journal (International Fortean Organization), Paul Willis.

Based on an approximate stratification and the

composition of the outer crust, the object has been dated from

250,000 to 500,000 BCE, but the name of the geologist who

provided the dating is not mentioned in any source material.

The construction is

reminiscent of modern attempts at superconductors. If

anyone would try to replicating the object using ceramic

superconductors and then cooling it off with liquid nitrogen, it

might be interesting to see what happens...

A 6-inch-high pot of bright yellow clay dating back two millennia contained a cylinder of sheet-copper 5 inches by 1.5 inches. The edge of the copper cylinder was soldered with a 60-40 lead-tin alloy comparable to today’s solder.

The bottom of the cylinder was capped with a crimped-in copper disk and sealed with bitumen or asphalt. Another insulating layer of asphalt sealed the top and also held in place an iron rod suspended into the center of the copper cylinder.

The rod showed evidence of having been corroded with

an acidic agent. With a background in mechanics, Dr. Konig

recognized this configuration was not a chance arrangement -

the clay pot was nothing less than an ancient electric

battery.

When the vases

were lightly tapped, a blue patina or film separated from the

surface, which is characteristic of silver electroplated onto

copper base. It would appear then that the Parthians inherited their batteries from one of the earliest known

civilizations.

One of them is the girdle from the tomb of Chinese general Chu (265-316 CE), which is made from an alloy of 85% aluminum with 10% copper and 5% manganese. The only viable method of production of aluminum from bauxite is electrolytic process, after alumina (aluminum chloride component of the ore) is dissolved in molten cryolite, patented in the middle of last century.

Needless to say, the Baghdad type of

batteries would not suffice, for quite a substantial

dynamo-generated current is needed.

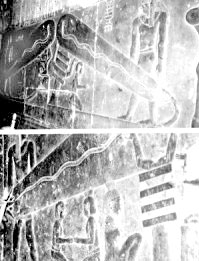

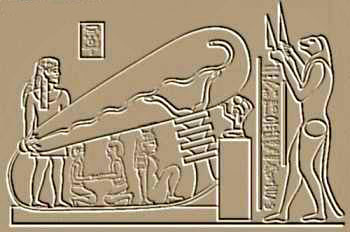

Well... very nicely put, at least from an egyptologists’ point of view. These snake-stones may have been set up on either side of entrances to temples or rooms assigned for the snake cult, supported by the symbols of stability, djed pillars, and held in place by priests.

On the other hand, Ivan Troëng, a Swedish writer, was apparently not well read in the egyptology materials.

In a book Kulturer Føre Istiden, 1964, he captioned a reproduction of the Dendera wall with the objects in question as:

The explanation of the glyphs stirred some passion amongst amateurs and experts alike.

But then something curious happened: the book got noticed by electrical engineers. As a group of professionals who could not care less about what other experts think, they commented on the picture with an unequivocal ’wow!’.

When shown the

archeology experts’ explanation of the glyphs, they found it

simply hilarious, according to Ivan Sanderson’s Investigating the Unexplained.

There was not much room for artistic license, bare the ability to arrange hieroglyphs in the most esthetic and space-conserving way.

Their canon specified precisely how certain things and their relationship must be presented, as is apparent on the relationship reflected in the depiction of gods, kings and common people, according to their importance.

The glyphs in Dendera strike me as odd in this context. You will notice that the depiction of Horus is rather small in comparison with people under the snake-stone, and the largest figure in the picture is not the priest (and even if there are two of them, holding the diorite stone of that size would be quite a feat), but the monkey with knives.

The monkey represents in a symbolic form danger for the

uninitiated. As it is the most prominent figure in the

depiction, we have to assume that the danger inherent in the

activity (whatever it was) must have been considerable.

The priests seem to be wearing some sort of goggles over their eyes (the second drawing does not contain the people, as it is only a schematic depiction of the objects in the scene). But if we forget the whole snake-stones business and look at these depictions as a representation of what they seem to imply, then certain symbols will start making some sense.

The snake symbol happens to be

very similar to the modern symbol of static electricity

and Horus represented, amongst other things, lightning.

Many good examples of how far the ancients went in this respect are found in The Sacred Mashroom and the Cross, by John Allegro.

Ivan Sanderson gives an example of analysis in an already mentioned publication, Investigating the Unexplained, done by an electromagnetics engineer, who knew nothing about the history or mythology of ancient Egyptians.

It is necessary to quote him verbatim for contextual meaning:

It is necessary to acknowledge the possibility that the devices depicted in Dendera may have had entirely different purpose than what is suggested in the analysis. But the recognition of an electromagnetic aspect of the glyphs seem to fit far better than the mythological interpretation.

Of course, considering that the Dendera glyphs have been ’explained’ predominantly during the last century when many devices in use today were yet to be invented, one may understand the confusion of the scholars when trying to interpret their meaning.

Thus a clear model of an airplane has been identified as ’wooden bird’, for

instance.

In the most wide use, it appears as a hieropglyph, representing the consonant ’dj’. In the glyphs where it has discernibly a character of an object, egyptologists interpret it as a symbol of stability and, in some sense, that is what it well may have been when used as an element in jewelry, for instance; but even there are implied, in one form on another, its original functions.

A typical example is a pendant, composed of a djed pilar inside an ankh, our already familiar Horus connecting the pillar with the loop of the ankh. The ankh is a symbol for life, but I am suspicious that it had another meaning, not dissimilar in its form to that of the djed pillar.

Again, the ankh form may

have had several meanings, depending on the context with other

devices. We can use as an analogy the modern

electronics schemes, in which the interpretation of any

simple symbol is apparent from the context with other symbols.

The device’s function as an insulator may be a fitting interpretation in some of the examples, but in others, it seems to be at odds with what the depiction represents.

In several djed representations, fins on the stand below four horizontal rings are attached. In some interpretations, one of which is illustrated in Sanderson’s book, they are vents for a battery located at the bottom of the pillar.

There the pillar is interpreted as a static electricity generator, based on the configuration as follows:

The baboons in this case may have

quite mundane meaning; it is known that priests-technicians

employed these creatures for menial jobs in the temples because

of their ’professional moronism’ - they, when trained, proved to

be more reliable than humans as they lacked the human propensity

for daydreaming.

The

charge is built up on the spherical surface until the potential

is sufficient to bridge the gap to the sphere above. The

discharge would appear as lightning. If the charge is powerful

enough, the upper sphere may start to glow, under certain

conditions. Of course, this is just a speculation, but possibly

closer to the actual purpose of the device than some

mythological explanation.

If we assume that the ’bulbs’ are, in fact, electron/cathode ray tubes, it would make a sense to interpret the pillars as some kind of ray bending device. Based on the ’ring’ used, a different function may have been achieved. This interpretation is suggested by the way the pillar is connected to the tube: in one case, the tube rests on the top of the pillar; in another the second ring is a base for two ’hands’ reaching to the tube; in a third case it’s the third ring from the top with arms holding the tube.

The rings may be,

in this case, magnets bending the ray.

The loop portion resting on an omphalos reminds one of the upper portion of ankh. Is there a connection? If there is, then the ankh may be something different than how it has been interpreted in the example with spheres.

The more I looked at the picture, the more the feeling that I was looking at something conceptually quite modern gained in intensity.

If we

assume that the rings on the djed are magnets (or

wiring with the function of generating the magnetic field), then

the loops placed on the symmetrically positioned omphaloses may

represent one of the two, either a stator or a rotor.

What we see here is, possibly, a very, very ancient electric

motor, albeit in a schematic form.

The ankh, for

instance, is generally interpreted as a symbol for life, but may

infer in context that something is alive. It may be a

coincidence, how an electrician would say that one of the wires

in your electric installation is live, but it is tempting to

assume that the ancients would handle certain concepts in a

similar way. What could be a better way to illustrate the

flow of a force?

That the staff-scepter has a connection to a force, power, energy is ascertained in myths, which not only originated in Egypt, but are corroborated also in Mesopotamian and Indus Valley materials. The gods have different names, but their attributes, that is, devices they used, are the same. The staff-scepter is described in all these sources as a paralyzing device, a personal weapon of the gods when pacifying the humans was the only way left to show who is the boss.

(For related and detailed information read The Earth Chronicles)

|

After

Mike Mikesell had ruined a diamond saw blade in cutting

it open, the geode proved to contain something strange.

In the middle of the geode was a metal core, about .08

inch (2 millimeters) in diameter.

After

Mike Mikesell had ruined a diamond saw blade in cutting

it open, the geode proved to contain something strange.

In the middle of the geode was a metal core, about .08

inch (2 millimeters) in diameter.  The

ancient battery in the Baghdad Museum, as well as those

others which were unearthed in Iraq, are all dated from

the Parthian occupation between 248 BCE and 226 CE. However, Dr. Konig also found copper vases plated with silver in the

Baghdad Museum, excavated from Sumerian sites in southern

Iraq, dating back to at least 2500 BCE.

The

ancient battery in the Baghdad Museum, as well as those

others which were unearthed in Iraq, are all dated from

the Parthian occupation between 248 BCE and 226 CE. However, Dr. Konig also found copper vases plated with silver in the

Baghdad Museum, excavated from Sumerian sites in southern

Iraq, dating back to at least 2500 BCE.  SITU

in England.

SITU

in England. Let’s

assume for a moment that the egyptologists’ explanation,

hilarious or not, is correct. It can be argued that ancient

Egyptians were very meticulous and pragmatic as far as their

recordings were concerned.

Let’s

assume for a moment that the egyptologists’ explanation,

hilarious or not, is correct. It can be argued that ancient

Egyptians were very meticulous and pragmatic as far as their

recordings were concerned.

I

would like to draw your attention towards the djed pillar.

It appears in many different forms and combinations with other

devices. Because of that, I have my doubts that the function of

the pillar has been identified correctly in the analysis

mentioned above.

I

would like to draw your attention towards the djed pillar.

It appears in many different forms and combinations with other

devices. Because of that, I have my doubts that the function of

the pillar has been identified correctly in the analysis

mentioned above.  As

seen on the illustration, the djed pillar was apparently

used in many different configurations. It does not necessarily

mean that it did not have a single, specific purpose, maybe in

some way reflected in the symbolic use of it for representing

stability.

As

seen on the illustration, the djed pillar was apparently

used in many different configurations. It does not necessarily

mean that it did not have a single, specific purpose, maybe in

some way reflected in the symbolic use of it for representing

stability.  Of

all the glyphs, I consider the representation on the right one

of the most intriguing. Its symmetry was the first thing which

attracted my attention. As I looked at the drawing, I could not

leave unnoticed the way the djed pillar encloses the two

symmetrically positioned objects. The objects themselves are

strange.

Of

all the glyphs, I consider the representation on the right one

of the most intriguing. Its symmetry was the first thing which

attracted my attention. As I looked at the drawing, I could not

leave unnoticed the way the djed pillar encloses the two

symmetrically positioned objects. The objects themselves are

strange.