|

by John A. Keel

from

GreyFalcon Website

In 1947, the editor of Amazing Stories watched in astonishment as

the things he had been fabricating for years in his magazine

suddenly came true!

North America's "Bigfoot" was nothing more than an Indian legend

until a zoologist named Ivan T. Sanderson began collecting

contemporary sightings of the creature in the early 1950s,

publishing the reports in a series of popular magazine articles. He

turned the tall, hairy biped into a household word, just as British

author Rupert T. Gould rediscovered sea serpents in the 1930s and,

through his radio broadcasts, articles, and books, brought Loch Ness

to the attention of the world.

Another writer named Vincent Gaddis

originated

the Bermuda Triangle in his 1965 book,

Invisible

Horizons: Strange Mysteries of the Sea. Sanderson and Charles Berlitz later added to the Triangle lore, and rewriting their books

became a cottage industry among hack writers in the United States.

Charles Fort put bread on the table of generations of science

fiction writers when, in his 1931 book Lo!, he assembled the many

reports of objects and people strangely transposed in time and

place, and coined the term "teleportation." And it took a politician

named Ignatius Donnelly to revive lost Atlantis and turn it into a

popular subject (again and again and again).1

But the man responsible for the most well-known of all such modern

myths - flying saucers - has somehow been forgotten. Before the

first flying saucer was sighted in 1947, he suggested the idea to

the American public. Then he converted UFO reports from what might

have been a Silly Season phenomenon into a subject, and kept that

subject alive during periods of total public disinterest. His name

was Raymond A. Palmer.

Born in 1911, Ray Palmer suffered severe injuries that left him

dwarfed in stature and partially crippled. He had a difficult

childhood because of his infirmities and, like many isolated young

men in those pre-television days, he sought escape in "dime novels,"

cheap magazines printed on coarse paper and filled with lurid

stories churned out by writers who were paid a penny a word.

He

became an avid science fiction fan, and during the Great Depression

of the 1930s he was active in the world of fandom - a world of

mimeographed fanzines and heavy correspondence. (Science fiction

fandom still exists and is very well organized with well-attended

annual conventions and lavishly printed fanzines, some of which are

even issued weekly.)

In 1930, he sold his first science fiction

story, and in 1933 he created the Jules Verne Prize Club which gave

out annual awards for the best achievements in sci-fi. A facile

writer with a robust imagination, Palmer was able to earn many

pennies during the dark days of the Depression, undoubtedly buoyed

by his mischievous sense of humor, a fortunate development motivated

by his unfortunate physical problems. Pain was his constant

companion.

In 1938, the Ziff-Davis Publishing Company in Chicago purchased a

dying magazine titled Amazing Stories. It had been created in 1929

by the inestimable Hugo Gernsback, who is generally acknowledged as

the father of modern science fiction. Gernsback, an electrical

engineer, ran a small publishing empire of magazines dealing with

radio and technical subjects. (he also founded Sexology, a magazine

of soft-core pornography disguised as science, which enjoyed great

success in a somewhat conservative era.)

It was his practice to sell

- or even give away - a magazine when its circulation began to slip.

Although Amazing Stories was one of the first of its kind, its

readership was down to a mere 25,000 when Gernsback unloaded it on

Ziff-Davis. William B. Ziff decided to hand the editorial reins to

the young science fiction buff from Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

At the age

of 28, Palmer found his life's work.

Expanding the pulp magazine to 200 pages (and as many as 250 pages

in some issues), Palmer deliberately tailored it to the tastes of

teenaged boys. He filled it with nonfiction features and filler

items on science and pseudo-science in addition to the usual formula

short stories of BEMs (Bug-Eyed Monsters) and beauteous maidens in

distress.

Many of the stories were written by Palmer himself under a

variety of pseudonyms such as Festus Pragnell and Thorton Ayre,

enabling him to supplement his meager salary by paying himself the

usual penny-a-word. His old cronies from fandom also contributed

stories to the magazine with a zeal that far surpassed their

talents. In fact, of the dozen or so science magazines then being

sold on the newsstands, Amazing Stories easily ranks as the very

worst of the lot.

Its competitors, such as Startling Stories,

Thrilling Wonder Stories, Planet Stories and the venerable

Astounding (now renamed Analog) employed skilled, experienced

professional writers like Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, and L. Ron

Hubbard (who later created Dianetics and founded Scientology).

Amazing Stories was garbage in comparison and hardcore sci-fi fans

tended to sneer at it.2

The magazine might have limped through the 1940s, largely ignored by

everyone, if not for a single incident.

Howard Browne, a television

writer who served as Palmer's associate editor in those days,

recalls:

"early in the 1940s, a letter came to us from Dick Shaver

purporting to reveal the "truth" about a race of freaks, called "Deros,"

living under the surface of the earth. Ray Palmer read it, handed it

to me for comment. I read a third of it, tossed it in the waste

basket. Ray, who loved to show his editors a trick or two about the

business, fished it out of the basket, ran it in Amazing, and a

flood of mail poured in from readers who insisted every word of it

was true because they'd been plagued by Deros for years."

3

Actually, Palmer had accidentally tapped a huge, previously

unrecognized audience. Nearly every community has at least one

person who complains constantly to the local police that someone -

usually a neighbor - is aiming a terrible ray gun at their house or

apartment.

This ray, they claim, is ruining their health, causing

their plants to die, turning their bread moldy, making their hair

and teeth fall out, and broadcasting voices into their heads.

Psychiatrists are very familiar with these "ray" victims and relate

the problem with paranoid-schizophrenia. For the most part, these

paranoiacs are harmless and usually elderly.

Occasionally, however,

the voices they hear urge them to perform destructive acts,

particularly arson. They are a distrustful lot, loners by nature,

and very suspicious of everyone, including the government and all

figures of authority. In earlier times, they thought they were

hearing the voice of god and/or the Devil. Today they often blame

the CIA or space beings for their woes.

They naturally gravitate to

eccentric causes and organizations which reflect their own fears and

insecurities, advocating bizarre political philosophies and

reinforcing their peculiar belief systems. Ray Palmer

unintentionally gave thousands of these people focus to their lives.

Shaver's long, rambling letter claimed that while he was welding 4 he

heard voices which explained to him how the underground Deros were

controlling life on the surface of the earth through the use of

fiendish rays.

Palmer rewrote the letter, making a novelette out of

it, and it was published in the March 1945 issue under the title:

"I

Remember Lemuria by Richard Shaver."

The Shaver Mystery was born.

Somehow the news of Shaver's discovery quickly spread beyond science

fiction circles and people who had never before bought a pulp

magazine were rushing to their local newsstands.

The demand for

Amazing Stories far exceeded the supply and Ziff-Davis had to divert

paper supplies (remember there were still wartime shortages) from

other magazines so they could increase the press run of AS.

"Palmer traveled to Pennsylvania to talk to Shaver," Howard Brown

later recalled, "found him sitting on reams of stuff he'd written

about the Deros, bought every bit of it and contracted for more. I

thought it was the sickest crap I'd run into. Palmer ran it and

doubled the circulation of Amazing within four months."

By the end of 1945, Amazing Stories was selling 250,000 copies per

month, an amazing circulation for a science fiction pulp magazine.

Palmer sat up late at night, rewriting Shaver's material and writing

other short stories about the Deros under pseudonyms. Thousands of

letters poured into the office.

Many of them offered supporting

"evidence" for the Shaver stories, describing strange objects they

had seen in the sky and strange encounters they had had with alien

beings. It seemed that many thousands of people were aware of the

existence of some distinctly nonterrestrial group in our midst.

Paranoid fantasies were mixed with tales that had the uncomfortable

ring of truth. The "Letters-to-the-Editor" section was the most

interesting part of the publication.

Here is a typical contribution

from the issue for June 1946:

Sirs:

I flew my last combat mission on May 26 [1945] when I was shot up

over Bassein and ditched my ship in Ramaree roads off Chedubs

Island. I was missing five days. I requested leave at Kashmere

(sic). I and Capt. (deleted by request) left Srinagar and went to

Rudok then through the Khese pass to the northern foothills of the

Karakoram. We found what we were looking for. We knew what we were

searching for.

For heaven's sake, drop the whole thing! You are playing with

dynamite. My companion and I fought our way out of a cave with

submachine guns. I have two 9" scars on my left arm that came from

wounds given me in the cave when I was 50 feet from a moving object

of any kind and in perfect silence. The muscles were nearly ripped

out. How? I don't know. My friend has a hole the size of a dime in

his right bicep. It was seared inside. How we don't know. But we

both believe we know more about the Shaver Mystery than any other

pair.

You can imagine my fright when I picked up my first copy of Amazing

Stories and see you splashing words about the subject.

The identity of the author of this letter was withheld by request.

Later Palmer revealed his name: Fred Lee Crisman. He had

inadvertently described the effects of a laser beam - even though

the laser wasn't invented until years later.

Apparently Crisman was

obsessed with Deros and death rays long before Kenneth Arnold

sighted the "first" UFO in June 1947.

In September 1946, Amazing Stories published a short article by W.C.

Hefferlin, "Circle-Winged Plane," describing experiments with a

circular craft in 1927 in San Francisco. Shaver's (Palmer's)

contribution to that issue was a 30,000 word novelette, "Earth

Slaves to Space," dealing with spaceships that regularly visited the

Earth to kidnap humans and haul them away to some other planet.

Other stories described amnesia, an important element in the UFO

reports that still lay far in the future, and mysterious men who

supposedly served as agents for those unfriendly Deros.

A letter from army lieutenant Ellis L. Lyon in the September 1946

issue expressed concern over the psychological impact of the Shaver

Mystery.

What I am worried about is that there are a few, and perhaps quite

large number of readers who may accept this Shaver Mystery as being

founded on fact, even as Orson Welles put across his invasion from

Mars, via radio some years ago. It is of course, impossible for the

reader to sift out in your "Discussions" and "Reader Comment"

features, which are actually letters from readers and which are

credited to an Amazing Stories staff writer, whipped up to keep

alive interest in your fictional theories.

However, if the letters

are generally the work of readers, it is distressing to see the

reaction you have caused in their muddled brains. I refer to the

letters from people who have "seen" the exhaust trails of rocket

ships or "felt" the influence of radiations from underground

sources.

Palmer assigned artists to make sketches of objects described by

readers and disc-shaped flying machines appeared on the covers of

his magazine long before June 1947. So we can note that a

considerable number of people - millions - were exposed to the

flying saucer concept before the national news media was even aware

of it.

Anyone who glanced at the magazines on a newsstand and caught

a glimpse of the saucers-adorned Amazing Stories cover had the image

implanted in his subconscious. In the course of the two years

between march 1945 and June 1947, millions of Americans had seen at

least one issue of Amazing Stories and were aware of the Shaver

Mystery with all of its bewildering implications.

Many of these

people were out studying the empty skies in the hopes that they,

like other Amazing Stories readers, might glimpse something

wondrous. World War II was over and some new excitement was needed.

Raymond Palmer was supplying it - much to the alarm of Lt. Lyon and

Fred Crisman.

Aside from Palmer's readers, two other groups were ready to serve as

cadre for the believers. About 1,500 members of Tiffany Thayer's

Fortean Society knew that weird aerial objects had been sighted

throughout history and some of them were convinced that this planet

was under surveillance by beings from another world.

Tiffany Thayer

was rigidly opposed to Franklin Roosevelt and loudly proclaimed that

almost everything was a government conspiracy, so his Forteans were

fully prepared to find new conspiracies hidden in the forthcoming

UFO mystery. They would become instant experts, willing to educate

the press and public when the time came. The second group were

spiritualists and students of the occult, headed by Dr. Meade Layne,

who had been chatting with the space people at seances through

trance mediums and Ouija boards.

They knew the space ships were

coming and hardly surprised when "ghost rockets" were reported over

Europe in 1946.5 Combined, these three groups represented a

formidable segment of the population.

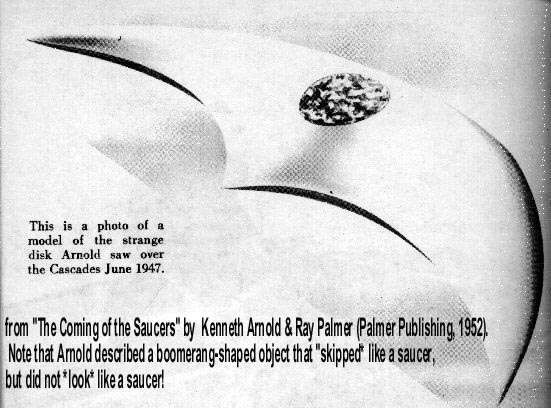

On June 24, 1947, Kenneth Arnold made his famous sighting of a group

of "flying saucers" over Mt. Rainier, and in Chicago Ray Palmer

watched in astonishment as the newspaper clippings poured in from

every state.

The things that he had been fabricating for his

magazine were suddenly coming true!

For two weeks, the newspapers were filled with UFO reports. Then

they tapered off and the Forteans howled "Censorship!" and

"Conspiracy!" But dozens of magazine writers were busy compiling

articles on this new subject and their pieces would appear steadily

during the next year. One man, who had earned his living writing

stories for the pulp magazines in the 930s, saw the situation as a

chance to break into the "slicks" (better quality magazines printed

on glossy or "slick" paper).

Although he was 44 years old at the

time of Pearl Harbor, he served as a Captain in the marines until he

was in a plane accident. Discharged as a Major (it was the practice

to promote officers one grade when they retired), he was trying to

resume his writing career when Ralph Daigh, an editor at True

magazine, assigned him to investigate the flying saucer enigma.

Thus, at the age of 50, Donald E. Keyhoe entered Never-Never-Land.

His article, "Flying Saucers Are Real," would cause a sensation, and

Keyhoe would become an instant UFO personality.

That same year, Palmer decided to put out an all-flying saucer issue

of Amazing Stories.

Instead, the publisher demanded that he drop the

whole subject after, according to Palmer, two men in Air Force

uniforms visited him. Palmer decided to publish a magazine of his

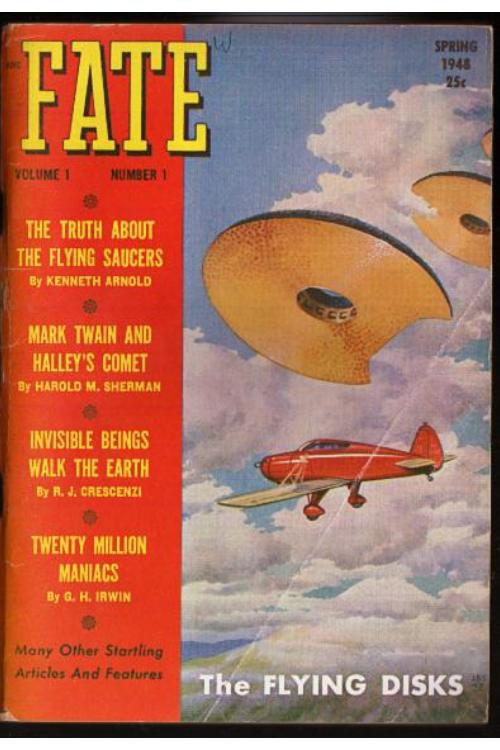

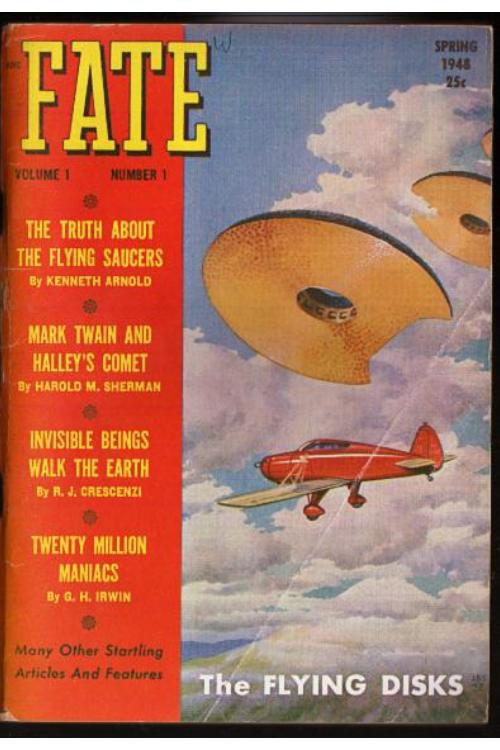

own. Enlisting the aid of Curtis Fuller, editor of a flying

magazine, and a few other friends, he put out the first issue of

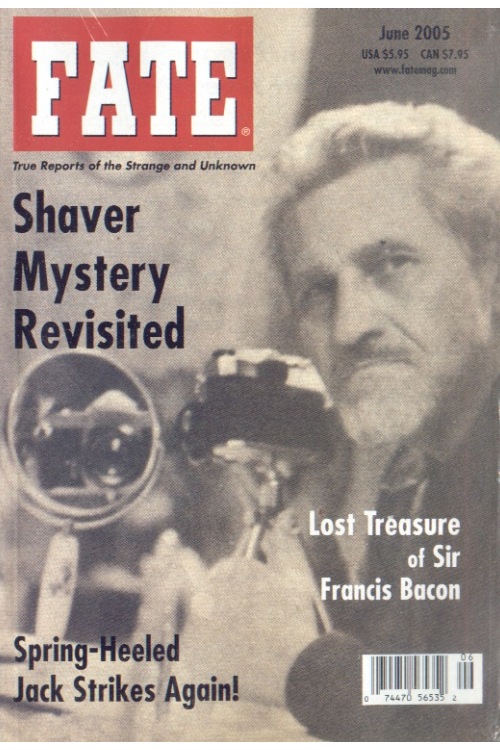

Fate in the spring of 1948. A digest-sized magazine printed on the

cheapest paper, Fate was as poorly edited as Amazing Stories and had

no impact on the reading public. But it was the only newsstand

periodical that carried UFO reports in every issue.

The Amazing

Stories readership supported the early issues wholeheartedly.

In the fall of 1948, the first flying saucer convention was held at

the Labor Temple on 14th Street in New York City. Attended by about

thirty people, most of whom were clutching the latest issue of Fate,

the meeting quickly dissolved into a shouting match.6

Although the

flying saucer mystery was only a year old, the side issues of

government conspiracy and censorship already dominated the situation

because of their strong emotional appeal. The U.S. Air Force had

been sullenly silent throughout 1948 while, unbeknownst to the UFO

advocates, the boys at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio were

making a sincere effort to untangle the mystery.

When the Air Force investigation failed to turn up any tangible

evidence (even though the investigators accepted the

extraterrestrial theory) General Hoyt Vandenburg, Chief of the Air

Force and former head of the CIA, ordered a negative report to

release to the public. The result was Project Grudge, hundreds of

pages of irrelevant nonsense that was unveiled around the time True

magazine printed Keyhoe's pro-UFO article. Keyhoe took this

personally, even though his article was largely a rehash of Fort's

book, and Ralph Daigh had decided to go with the extraterrestrial

hypothesis because it seemed to be the most commercially acceptable

theory (that is, it would sell magazines).

Palmer's relationship with Ziff-Davis was strained now that he was

publishing his own magazine.

"When I took over from Palmer, in

1949," Howard Browne said, "I put an abrupt end to the Shaver

Mystery - writing off over 7,000 dollars worth of scripts."

Moving to Amherst, Wisconsin, Palmer set up his own printing plant

and eventually he printed many of those Shaver stories in his Hidden

Worlds series. As it turned out, postwar inflation and the advent of

television was killing the pulp magazine market anyway. In the fall

of 1949, hundreds of pulps suddenly ceased publication, putting

thousands of writers and editors out of work.

Amazing Stories has

often changed hands since but is still being published, and is still

paying its writers a penny a word.7

For some reason known only to himself, Palmer chose not to use his

name in Fate. Instead, a fictitious "Robert N. Webster" was listed

as editor for many years. Palmer established another magazine,

Search, to compete with Fate. Search became a catch-all for inane

letters are occult articles that failed to meet Fate's low

standards.

Although there was a brief revival of public and press interest in

flying saucers following the great wave of the summer of 1952, the

subject largely remained in the hands of cultists, cranks,

teenagers, and housewives who reproduced newspaper clippings in

little mimeographed journals and looked up to Palmer as their

fearless leader.

In June, 1956, a major four-day symposium on UFOs was held in

Washington, D.C. It was unquestionably the most important UFO affair

of the 1950s and was attended by leading military men, government

officials and industrialists. Men like William Lear, inventor of the

Lear Jet, and assorted generals, admirals and former CIA heads

freely discussed the UFO "problem" with the press. Notably absent

were Ray Palmer and Donald Keyhoe.

One of the results of the

meetings was the founding of the National Investigation Committee on

Aerial Phenomena (NICAP) by a physicist named Townsend Brown.

Although the symposium received extensive press coverage at the

time, it was subsequently censored out of UFO history by the UFO

cultists themselves - primarily because they had not participated in

it.8

The American public was aware of only two flying saucer

personalities, contactee George Adamski, a lovable rogue with a

talent for obtaining publicity, and Donald Keyhoe, a zealot who

howled "Coverup!" and was locked in mortal combat with Adamski for

newspaper coverage. Since Adamski was the more colorful (he had

ridden a saucer to the moon), he was usually awarded more attention.

The press gave him the title of "astronomer" (he lived in a house on

Mount Palomar where a great telescope was in operation), while Keyhoe attacked him as "the operator of a hamburger stand."

Ray

Palmer tried to remain aloof of the warring factions, so naturally,

some of them turned against him.

The year 1957 was marked by several significant developments. There

was another major flying saucer wave. Townsend Brown's NICAP

floundered and Keyhoe took it over. And Ray Palmer launched a new

newsstand publication called Flying Saucers From Other Worlds. In

the early issues he hinted that the knew some important "secret."

After tantalizing his readers for months, he finally revealed that

UFOs came from the center of the earth and the phrase From Other

Worlds was dropped from the title. His readers were variously

enthralled, appalled, and galled by the revelation.

For seven years, from 1957 to 1964, ufology in the United States was

in total limbo. This was the Dark Age. Keyhoe and NICAP were buried

in Washington, vainly tilting at windmills and trying to initiate a

congressional investigation into the UFO situation.

A few hundred UFO believers clustered around Coral Lorenzen's

Aerial

Phenomena Research Organization (APRO). And about 2,000 teenagers

bought Flying Saucers from newsstands each month. Palmer devoted

much space to UFO clubs, information exchanges, and

letters-to-the-editor. So it was Palmer, and Palmer alone, who kept

the subject alive during the Dark Age and lured new youngsters into

ufology.

He published his strange books about Deros, and ran a

mail-order business selling the UFO books that had been published

after various waves of the 1950s. His partners in the Fate venture

bought him out, so he was able to devote his full time to his UFO

enterprises.

Palmer had set up a system similar to sci-fi fandom, but with

himself as the nucleus. He had come a long way since his early days

and the Jules Verne Prize Club. He had been instrumental in

inventing a whole system of belief, a frame of reference - the

magical world of Shaverism and flying saucers - and he had set

himself up s the king of that world.

Once the belief system had been

set up it became self-perpetuating. The people beleaguered by

mysterious rays were joined by the wishful thinkers who hoped that

living, compassionate beings existed out there beyond the stars.

They didn't need any real evidence. The belief itself was enough to

sustain them.

When a massive new UFO wave - the biggest one in U.S. history -

struck in 1964 and continued unabated until 1968, APRO and NICAP

were caught unawares and unprepared to deal with renewed public

interest. Palmer increased the press run of Flying Saucers and

reached out to a new audience. Then in the 1970s, a new Dark Age

began.

October 1973 produced a flurry of well-publicized reports and

then the doldrums set in. NICAP strangled in its own confusion and

dissolved in a puddle of apathy, along with scores of lesser UFO

organizations. Donald Keyhoe, a very elder statesman, lives in

seclusion in Virginia. Most of the hopeful contactees and UFO

investigators of the 1940s and 50s have passed away. Palmer's Flying

Saucers quietly self-destructed in 1975, but he continued with

Search until his death in 1977.

Richard Shaver is gone but the

Shaver Mystery still has a few adherents.

Yet the sad truth is that

none of this might have come about if Howard Browne hadn't scoffed

at that letter in that dingy editorial office in that faraway city

so long ago.

Footnotes

1. Donnelly's book, Atlantis, published in 1882, set off a 50-year

wave of Atlantean hysteria around the world. Even the characters who

materialized at seances during that period claimed to be Atlanteans.

2. The author was an active sci-fi fan in the 1940s and published a

fanzine called Lunarite. Here's a quote from Lunarite dated October

26, 1946: "Amazing Stories is still trying to convince everyone that

the BEMs in the caves run the world. And I was blaming it on the

Democrats. 'Great Gods and Little Termites' was the best tale in

this ish [issue]. But Shaver, author of the 'Land of Kui,' ought to

give up writing. He's lousy. And the editors of AS ought to joint

Sgt. Saturn on the wagon and quit drinking that Xeno or the BEMs in

the caves will get them."

I clearly remember the controversy created by the Shaver Mystery and

the great disdain with which the hardcore fans viewed it.

3. From Cheap Thrills: An Informal History of the Pulp Magazines by

Ron Goulart (published by Arlington House, New York, 1972).

4. It is interesting that so many victims of this type of phenomenon

were welding or operating electrical equipment such as radios,

radar, etc. when they began to hear voices.

5. The widespread "ghost rockets" of 1946 received little notice in

the U.S. press. I remember carrying a tiny clipping around in my

wallet describing mysterious rockets weaving through the mountains

of Switzerland. But that was the only "ghost rocket" report that

reached me that year.

6. I attended this meeting but my memory of it is vague after so

many years. I cannot recall who sponsored it.

7. A few of the surviving science fiction magazines now pay (gasp!)

three cents a word. But writing sci-fi still remains a sure way to

starve to death.

8. When David Michael Jacobs wrote The UFO Controversy in America, a

book generally regarded as the most complete history of the UFO

maze, he chose to completely revise the history of the 1940s and

50s, carefully excising any mention of Palmer, the 1956 symposium,

and many of the other important developments during that period.

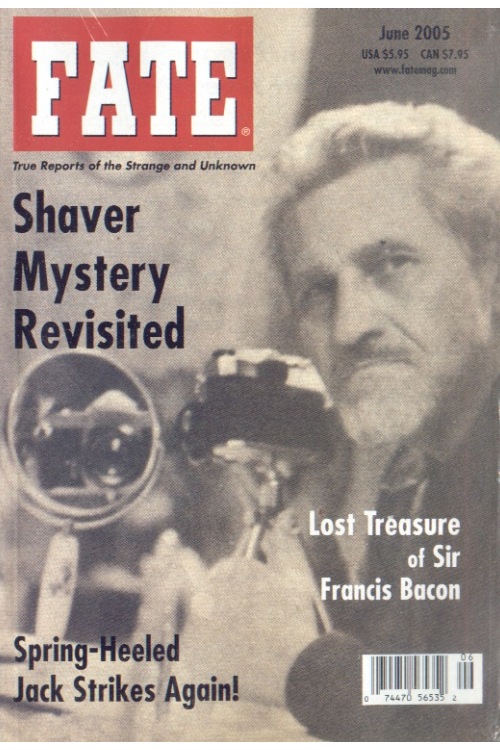

What's This? A Shaver Revival?

by Doug Skinner

|

Doug Skinner is a Fortean writer/artist/ and Off-Broadway (with Bill

Irwin) performer in The Amazing Stories of Richard Shaver. |

Richard Sharpe Shaver died 30 years ago. He was never famous in the

usual sense of the word, but the “Shaver Mystery” and the “rock

books” were once hot topics in certain circles. That was a long time

ago, however, and Shaver ought to be forgotten by now. Surprisingly,

he has remained stubbornly alive, and in an unexpected place—the art

world.

Maybe it’s time to reassess him; maybe we can even clear up a

few puzzles and misconceptions.

Shaver’s Early Life

Richard Shaver (he added the “Sharpe” himself later) was born in

1907; he was one of five children. At least two other members of his

family were writers: his mother, Grace, was a published poet, and

his brother Taylor contributed to Boys’ Life and other magazines.

Dick was a smart and bookish boy, surrounded by writers and readers.

He grew into a rather restless teen, and had discipline problems in

high school.

The family moved around a lot; maybe that had something

to do with it.

At any rate, by 1930 he was living in Detroit, intent on a career as

an artist. He enrolled in the Wicker School, where he also worked as

a life model to help meet his tuition. He became a great fan of the

muralist Diego Rivera and dabbled in progressive politics; his

speech at a Mayday rally that year put his picture in the paper.

The Wicker School eventually fell victim to the crumbling 1930s

economy. Shaver married one of his teachers, Sophie Gurivich, and

the two soon had a daughter, Evelyn Ann. Postponing his own artistic

career, he found work as a spot welder at the Briggs Auto Body

Plant.

Shaver had always been somewhat unstable, but now he began to have

serious troubles at work. He started hearing voices—at first only

when he was welding, then more and more often. His fellow workers’

thoughts rang through his head. Even more disturbingly, he heard

underground beings gloating over horrible tortures.

In 1934, Shaver’s brother Taylor died suddenly, of cardiac

hypertrophy. The two were close, and Richard took the news hard. He

recalled later that he reacted by drinking until he passed out. Only

six months later, he was admitted to Detroit Receiving Hospital. He

insisted that a demon called Max had killed his brother, and was now

after him as well. He was diagnosed as insane, and had to be

restrained.

Soon after that, Sophie had him transferred to Ypsilanti State

Hospital. He must have responded to treatment, since he was released

to visit his parents for Christmas in 1936. It was there that he

learned of another tragedy: Sophie had been killed, electrocuted

when she moved a heater in the bathtub. Her family took custody of

their daughter. Shaver did not return to Ypsilanti.

He was certain now that devils were persecuting him. Over the next

few years, he wandered aimlessly and compulsively, trying to shake

off the creatures that he believed had killed his wife and brother.

He often reminisced about this period later, but his accounts are

confused and contradictory; he confessed that he had trouble

separating reality from dreams and visions. He tried to stow away in

a ship to England; he was imprisoned a few times; he was tormented

by giant spiders; he returned to a mental hospital at some point.

Max was always after him.

Discovery of the Dero

Later, Shaver would insist that he had discovered an old and

jealously guarded secret during this period. Nydia, a blind girl he

had seen in dreams and visions, “a form as light in its step as the

sea foam that drifted up and touched the beach,” took him down into

the ancient network of caverns built by the giant godlike race that

had colonized Earth eons ago.

There, the halls were still stocked

with their “mech,” machines far in advance of our own: telaugs that

transmit thoughts, stim rays that amplify sexual pleasure,

telesolidographs that beam images through rock. When the sun turned

radioactive, these alien Titans escaped.

The few that remained

devolved into two warring races: the dero, whose brains were so

poisoned that they thought backwards and could only do evil; and the

tero, who tried to fight the dero and to assist surface men. In the

language of the caves, “de” meant “detrimental energy” and “ro”

slave: a dero, then, was a slave to destructive impulses. A tero was

the opposite, a slave to constructive forces. Max was a typical

dero, Nydia a tero.

The details of his story changed at times—Nydia came to him in a

Vermont prison, or from a Maryland fishing shack—but his conviction

that he had visited the caves never wavered. He always insisted that

he had pinched himself when he was there, and that it hurt.

He

returned to the surface to pick up some of his belongings, and

couldn’t find his way back.

Collaborations with Palmer

Shaver was released from the Ionia State Hospital in Michigan in

1943. He went to live with his parents in Barto, a small town in

Pennsylvania, and found work as a crane operator. A second marriage

foundered after a few months, but his third, to Dorothy Erb, was

apparently a happy one. And then he started writing to Ray Palmer.

Palmer, a prolific pulp writer in all genres, had taken over the

editorship of Amazing Stories in 1938. Its founder, Hugo Gernsback,

had pioneered science fiction—or “scientifiction,” as it was then

called—with stories rooted in scientific accuracy and technological

prophecy. Palmer slanted the magazine more toward fantasy and

adventure. Purists may have preferred Gernsback, but Palmer’s

approach proved far more commercial.

Palmer was always looking for new ideas, new writers, and new

gimmicks. So when Shaver sent in a key to the meaning of the

alphabet, Palmer was willing to try it out.

He printed it, and the

readers had fun with it, so he asked Shaver for more.

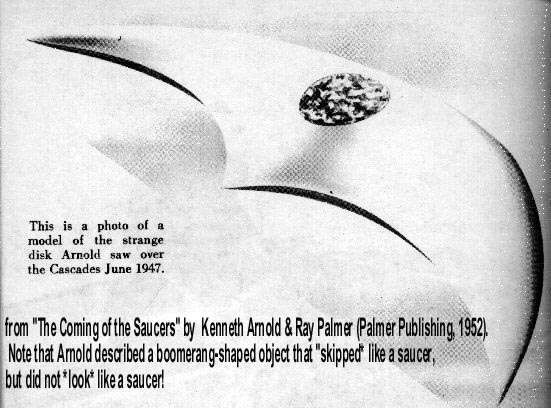

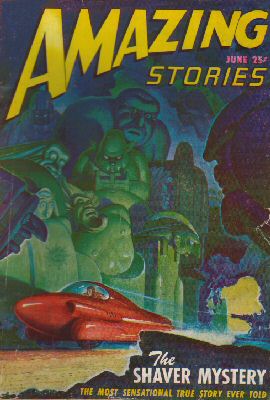

June 1947 issue of Amazing Stories

Shaver responded with stories about the caves and the dero, and

Palmer published most of them. Some readers were enthralled, and

some enraged, but the controversy was good for sales: circulation

increased from 135,000 to 185,000, and Amazing Stories went from a

quarterly to a monthly.

Palmer called the affair “The Shaver

Mystery” and it dominated the magazine from 1945 to 1950.

A number of misconceptions have arisen about those years. Palmer was

often accused of perpetrating a hoax by rewriting Shaver’s letters

as fiction. In fact, the correspondence between Palmer and Shaver

(which Palmer later published) showed that the two men worked

together to turn Shaver’s ideas into salable stories. Shaver was a

longtime fantasy fan and was happy for a chance to break into a

profession that promised more than the 83 cents an hour he made at

Bethlehem Steel.

His early attempts—particularly the first one, “I

Remember Lemuria!”—were thoroughly reworked by Palmer.

But Shaver

was determined to improve, and collaborated with other writers to

polish his output. He conferred with Palmer about style and subject;

he even sent sketches of his characters to the art director. And he

wrote non-cave stories as well: fantasy and adventure yarns for

Fantastic, Mammoth Adventure, and the other pulps that Palmer also

edited for the same publishing house, Ziff-Davis.

Shaver’s main literary model was Abraham Merritt. Merritt isn’t read

much today, but his fantasy novels were quite popular throughout the

’20s and ’30s. Beginning with The Moon Pool in 1919, he produced a

series of novels about underground caverns, lost races, ancient ray

machines, shell-shaped hovercraft, and other marvels.

He was also a

member of the original Fortean Society and the editor of The

American Weekly, a Sunday newspaper supplement that often featured

scientific and historical oddities. Shaver thought Merritt had seen

the caves but could only mention them in fiction. One might also

suspect that Merritt’s novels had influenced Shaver’s beliefs.

Shaver was serious about his mission: the dero were ruining our

lives and needed to be exposed. Palmer was not convinced, but he was

intrigued by Shaver’s unorthodox scientific ideas, wild imagination,

and ingenious interpretations of mythology. He didn’t question that

Shaver had seen strange things, but thought that the caves were

probably astral or ethereal rather than physical. To Shaver, a

staunch materialist, this was “dero wool.”

Thousands of readers wrote in with their own experiences, and Palmer

liked to cite them as evidence for Shaver’s claims. This too has

been misunderstood. Many letters did describe caves and dero—some of

which, I suspect, were written by Palmer himself.

But Palmer lumped

all Fortean, paranormal, and psychic subjects into the Shaver

Mystery; it could all, somehow, be connected to Shaver.

The Birth of Fate

After a few years of this, Amazing Stories became primarily a forum

for these subjects. There weren’t many alternatives back then,

except for a few privately circulated newsletters.

Palmer had

stumbled onto an unexpected audience.

The Mystery peaked in June 1947, with a special issue loaded with

Shaver stories and essays—and a Vincent Gaddis article on spaceship

sightings that presaged the flying saucer craze that was soon to

follow. In fact, when Kenneth Arnold’s sighting made news that

month, both Shaver and Palmer saw it as further proof of the caves.

After all, Shaver’s stories had long sported spacecraft, and Palmer

had been writing editorials about alien visitors and government

cover-ups since 1946.

By this time, many readers—and, more critically, Messrs. Ziff and

Davis—were getting tired of Shaver. He couldn’t prove his claims,

and the stories were getting repetitive. Many were also alarmed by

Shaver’s unbridled sexuality—Palmer once had to snip out a 50-page

bedroom scene. Shaver agreed to stick to straight-ahead fiction, and

the dero were confined to The Shaver Mystery Magazine, a smaller

magazine he started with one of his collaborators, Chester Geier.

Meanwhile, Palmer and another Ziff-Davis editor, Curtis Fuller, had

founded a new digest to cater to this newfound audience for the

paranormal. They called it Fate, and it did so well that Palmer quit

Ziff-Davis to devote himself to it. For some reason, he edited it

under the name of Robert N. Webster. Despite regular ads for the

book edition of I Remember Lemuria, Shaver was never featured in it.

A 1950 article on him was not well received—one irate subscriber

called it “entertainment for morons.”

Fate, though, wasn’t quite what Palmer was after. Within a few

years, he left to start his own line of magazines: Mystic (later

Search), Other Worlds, Flying Saucers, Space World—many of which

changed titles and formats erratically. Shaver wrote for several of

them. Despite spiraling costs and poor health, Palmer kept his

creations afloat, even when he had to print them on remaindered

paper and could no longer afford to pay contributors.

The new editor of Amazing Stories, Howard Browne, didn’t like

Shaver’s work—he once called it “the sickest crap I’d run across.”

With that outlet gone, Shaver’s writing career declined. He sold a

few pieces to other magazines (like If), but mostly appeared in

fanzines and Palmer publications. UFO buffs did their best to keep

the Mystery alive; the idea that the saucers came from underground

was popular in UFO publications and became a regular subject on Long

John Nebel’s nightly radio talk show. Still, Shaver wasn’t selling

many stories.

He suffered from depression and took to spending long

hours in the bathtub.

Rock Pictures

Sometime in the ’50s, however, he made a discovery that came to

dominate his life. One day, his wife dumped a handful of stones on

his desk, remarking that they seemed to have pictures on them. After

studying them, he decided that they weren’t just stones, but the

books of an ancient race of sea people. He had found the evidence

that had always eluded him: physical proof of the elder races.

These rocks, Shaver believed, were the records of the giant mermaids

and mermen who had developed a rich civilization eons ago, before

the moon fell and bounced off the earth. They made books by

projecting images into rock as it hardened. These images were

complex and variable; there were pictures that changed from

different perspectives, and pictures under and inside one another.

Shaver concluded that these “rock books” must have been projected,

like movie film, by some long-lost machine.

Shaver worked tirelessly to publicize his rocks. He photographed

them, wrote about them, and tried to sell them through the mail. He

made very few converts.

Eventually, Shaver turned to painting to show the pictures that

nobody else seemed able to see. His method was somewhat unusual. A

sheet of cardboard or plywood was first coated with a variety of

chemicals, chosen to simulate the texture of rock and to “respond

easily to the minute light forces.”

Shaver had no set mixture, but

experimented with different combinations of laundry soap, wax,

Windex, glue flakes, dye, and diluted paint. He also tried fixative,

but abandoned it when Dorothy complained about the smell. A rock was

then sawed open and set on an opaque projector. Once the image was

focused onto the cardboard, he sprinkled water over it and gave the

picture time to form. Only then did he get out his paints to

carefully touch it up clarify it.

The resulting paintings were fluid and hallucinatory: distorted

dream-like visions of faces, battles, mermaids, and strange

creatures. And, always, naked women.

“Oh yes, they were sexy, these

voluptuous ancient sea people!” Shaver explained.

He insisted that

the paintings weren’t his own creations, but strictly documentation.

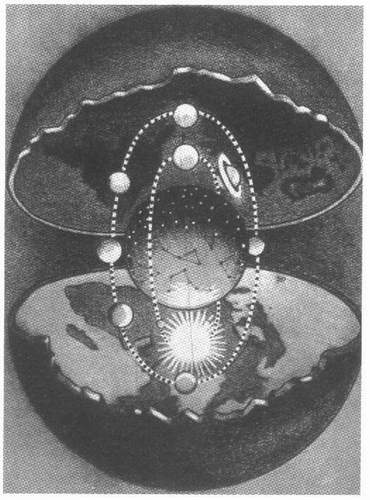

The mythical realms of Agartha and Shambala

Shaver devoted most of his later life to painting and to promoting

the rock books. Palmer published a hardcover book, The Secret World,

that preserved many of the paintings and rock photos (as well as an

installment of Palmer’s memoirs), and a 16-volume series, The Hidden

World, that collected both early and late Shaveriana.

Palmer also

revealed in an interview that Shaver had been confined to a mental

hospital for much of the time that he claimed to have spent in the

caves, which didn’t help either of their reputations.

Shaver himself

planned a long treatise on the rocks, The Layman’s Atlantis; he

printed a few chapters as booklets in 1970.

Reborn as Outsider Artist

Shaver’s writings have been largely ignored since his death. Many of

them, I would suggest, deserve a better fate. Some are just standard

space opera, but others are not quite like anything else in

literature.

“Erdis Cliff” (Amazing Stories, September 1949), for

example, manages to combine heretical physics, a talking purple pig,

atheism, Greek mythology, excerpts from the channeled Bible OAHSPE,

and an orgy led by Satan—who, we learn, is actually a harmless but

lusty cave alien. Nor, for that matter, is there anything quite like

the disturbing and hallucinatory memoir “The Dream-Makers”

(Fantastic, July 1958).

I also enjoy Shaver’s articles for Palmer’s

Forum, which treat environmental and social issues from Shaver’s own

soulful, quirky perspective.

Shaver’s rock art, however, has found a wider audience.

Brian Tucker

organized an exhibit at the California Institute of the Arts in

1989, and at Chapman University in Orange, California, in 2002. The

LA Weekly wrote about the latter show that Shaver’s work “ranks with

the Surrealist paintings of Max Ernst and Jean Dubuffet.”

Shaver’s

work has also been shown at the Curt Marcus Gallery in New York City

in 1989 and at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco

in 2004. Norman Brosterman exhibited some of his collection at the

Christine Burgin Art Gallery and at the Outsider Art Fair in New

York City. Rock photos have been published in recent issues of

Cabinet and The Ganzfeld.

Posterity will have to decide whether Shaver’s art is to be

remembered. I can only add that I have one of his paintings, and

like looking at it.

Meanwhile, some of Shaver’s fans continue to

keep his memory alive—particularly Jim Pobst (to whom I’m indebted

for his research into Shaver’s early years) and Richard Toronto,

whose indispensable website can be found at

www.shavertron.com.

Our Own Worst Enemies

There’s a hidden message in Shaver’s work, one that’s often

overlooked by both enthusiasts and detractors.

Quite simply: We are

the dero.

To Shaver, we have virtually unlimited potential. Within us is a

huge untapped capacity for wisdom, strength, vitality, and beauty.

We could be like gods. Instead, we’re a stunted, perverted bunch: we

kill one another, poison our planet, stultify ourselves with

mindless jobs, cut down forests to put up ugly boxlike cities,

vilify intelligence, and condemn sexuality. We think backwards and

embrace everything that’s vile, nasty, and foolish.

Shaver may have been overly optimistic about our capabilities, but

he did have a point.

We can do better.

And if it takes a Shaver

revival to get that into our little dero heads, we might as well

have one.

|