|

from BigThink Website

Image Credit: jeanbaptisteparis / Flickr.

The wall in question is

the network of pay-walls that cuts off tens of thousands of students

and researchers around the world, at institutions that can't afford

expensive journal subscriptions, from accessing scientific research.

The website works in two stages, firstly by attempting to download a copy from the LibGen database of pirated content, which opened its doors to academic papers in 2012 and now contains over 48 million scientific papers.

The ingenious part of the system is that if LibGen does not already have a copy of the paper, Sci-hub bypasses the journal pay-wall in real time by using access keys donated by academics lucky enough to study at institutions with an adequate range of subscriptions.

This allows Sci-Hub to route the user straight to the paper through publishers such as,

After delivering the

paper to the user within seconds, Sci-Hub donates a copy of the

paper to LibGen for good measure, where it will be stored forever,

accessible by everyone and anyone.

Before September 2011, there was no way for people to freely access pay-walled research en masse; researchers like Elbakyan were out in the cold.

Sci-Hub is the first

website to offer this service and now makes the process as simple as

the click of a single button.

Elbakyan explains,

This may well be no exaggeration.

Elsevier, one of the most prolific and controversial scientific publishers in the world, recently alleged in court that Sci-Hub is currently harvesting Elsevier content at a rate of thousands of papers per day.

Elbakyan puts the number

of papers downloaded from various publishers through Sci-Hub in the

range of hundreds of thousands per day, delivered to a running total

of over 19 million visitors.

Users now don't even have to visit the Sci-Hub website at all; instead, when faced with a journal pay-wall they can simply take the Sci-Hub URL and paste it into the address bar of a pay-walled journal article immediately after the ".com" or ".org" part of the journal URL and before the remainder of the URL.

When this happens, Sci-Hub

automatically bypasses the pay-wall, taking the reader straight to a

PDF without the user ever having to visit the Sci-Hub website

itself.

In one fell swoop, a network has been created that likely has a greater level of access to science than any individual university, or even government for that matter, anywhere in the world.

Sci-Hub represents the

sum of countless different universities' institutional access -

literally a world of knowledge. This is important now more than ever in a world where even Harvard University can no longer afford to pay skyrocketing academic journal subscription fees, while Cornell axed many of its Elsevier subscriptions over a decade ago.

For researchers outside the US' and Western Europe's richest institutions, routine piracy has long been the only way to conduct science, but increasingly the problem of unaffordable journals is coming closer to home.

This was the experience of Elbakyan herself, who studied in Kazakhstan University and just like other students in countries where journal subscriptions are unaffordable for institutions, was forced to pirate research in order to complete her studies.

Elbakyan told me,

So, how did researchers like Alexandra Elbakyan ever survive before Sci-Hub?

Elbakyan explains,

This practice is widespread even today, with researchers even at rich Western institutions now routinely forced to email the authors of papers directly, asking for a copy by email, wasting the time of everyone involved and holding back the progress of research in the process.

Today many researchers use the #icanhazpdf hashtag on Twitter to ask other benevolent researchers to download pay-walled papers for them, a practice Elbakyan describes as "very archaic," pointing out that,

Last year, New York District Court Judge Robert W. Sweet delivered a preliminary injunction against Sci-Hub, making the site's former domain unavailable.

The injunction came in the run-up to the forthcoming case of Elsevier vs. Sci-Hub, a case Elsevier is expected to win - due, in no small part, because no one is likely to turn up on U.S. soil to initiate a defence.

Elsevier alleges "irreparable harm," based on statutory damages of $750-$150,000 for each pirated work.

Given that Sci-Hub now holds a library of over 48 million papers Elsevier's claim runs into the billions, but can be expected to remain hypothetical both in theory and in practice.

Elsevier is the world's largest academic publisher and by far the most controversial.

Over 15,000 researchers have vowed to boycott the publisher for charging "exorbitantly high prices" and bundling expensive, unwanted journals with essential journals, a practice that allegedly is bankrupting university libraries.

Elsevier also supports SOPA and PIPA, which the researchers claim threatens to restrict the free exchange of information.

Elsevier is perhaps most notorious for delivering takedown notices to academics, demanding them to take their own research published with Elsevier off websites like Academia.edu.

The movement against Elsevier has only gathered speed over the course of the last year with the resignation of 31 editorial board members from the Elsevier journal Lingua, who left in protest to set up their own open-access journal, Glossa.

Now the battleground has moved from the comparatively niche field of linguistics to the far larger field of cognitive sciences.

Last month, a petition of over 1,500 cognitive science researchers called on the editors of the Elsevier journal Cognition to demand Elsevier offer "fair open access".

Elsevier currently charges researchers $2,150 per article if researchers wish their work published in Cognition to be accessible by the public, a sum far higher than the charges that led to the Lingua mutiny.

In a letter to the judge, Elbakyan defended her decision not on legal grounds, but on ethical grounds.

Elbakyan writes:

In her letter to Sweet, Elbakyan made a point that will likely come as a shock to many outside the academic community:

Elbakyan explains:

This is the Catch-22...

Why would any self-respecting researcher willingly hand over, for nothing, the copyright to their hard work to an organization that will profit from the work by making the keys prohibitively expensive to the few people who want to read it?

The answer is ultimately all to do with career prospects and prestige. Researchers are rewarded in jobs and promotions for publishing in high-ranking journals such as Nature.

Ironically, it is becoming increasingly common for researchers to be unable to access even their own published work, as wealthier and wealthier universities join the ranks of those unable to pay rising subscription fees.

Another tragic irony is the fact that high-impact journals can actually be less reliable than lesser-ranked journals, due to their requirements that researchers publish startling results, which can lead to a higher incidence of fraud and bad research practices.

But things are changing.

Researchers are increasingly fighting back against the problem of closed-access publishers and now funders of research such as the Wellcome Trust are increasingly joining the battle by instituting open access policies banning their researchers from publishing in journals with closed access. But none of this helps researchers who need access to science right now.

For her part, Elbakyan isn't giving up the fight, in spite of the growing legal pressure, which she feels is totally unjust.

When I asked what her next move would be, Elbakyan said,

Already, only days after the court injunction blocking Sci-Hub's old domain, Sci-Hub was back online at a new domain accessible worldwide.

Since the court judgment, the website has been upgraded from a barebones site that existed entirely in Russian to a polished English version proudly boasting a library of 48 million papers, complete with a manifesto in opposition to copyright law.

The bird is out of its cage, and if Elsevier still thinks it can put it back, they may well be sorely mistaken.

Update 02/16/16

Since last week's deluge of traffic to Sci-Hub following this story Google have blocked Sci-Hub's access to Google Scholar, making the search function temporarily defunct.

The service otherwise works as before, users simply have to find the link to the paper they need unlocked themselves, and insert Sci-hub's complete URL into the domain as discussed above.

When I asked Alexandra about this setback she was completely unfazed, explaining,

Ironically, the Google Scholar block may actually work in Sci-Hub's favor Alexandra explains, not having to perform the complex task of managing searches, the server can now work much faster when handling the same amount of queries.

Alexandra is now working on creating a "Google-like" search method, that could potentially result in "a more sophisticated" solution than Google Scholar.

Part 2

Contains references to violence, injustice, suicide and material you may find upsetting,

you might not want to read this on the bus.

The moment I started working on this story last October I knew it was a huge story.

I knew it deserved to be read not just by the hundreds of thousands of people who are now reading and sharing it. I knew it deserved to be in newspapers around the world.

So I did what any science journalist would do. I pitched it to The New York Times; I pitched it to The Guardian; I pitched it to all the big guns.

The response? Crickets. Bizarrely, until the day that I broke the story last week not one publication had ever covered the story of Sci-Hub. Since last week, dozens have.

The only publication that gave any indication of interest happened to be the largest publisher in tech news.

For a time things sounded very promising; but discussions eventually broke down when I made it clear that it was impossible for me to convince Alexandra to travel to Europe for a photoshoot. She feared arrest, quite understandably...

Discussions reached a deadlock as I was placed under immense pressure to cut the story down, ultimately to less than 250 words, barely a couple of paragraphs.

Apparently the story was not worth being printed on paper without glossy photos of Alexandra herself posing for the camera, as if they were remotely relevant to the story. A story of this complexity simply couldn't be covered in any meaningful way in 250 words, I argued.

That has since proven to be true as vast numbers of people who read the story thought researchers or universities received a portion of the fees paid by the public to read the journals, which contain academic research funded by taxpayers.

This is simply not true. Most of the billions of dollars that are paid every year for access to academic publications are creamed off, directly into the pockets of publishing fat cats and their shareholders.

Not a penny of this is paid to a scientist or academic institution. In fact if anything, scientists must pay for their work to be published. Editing, reviewing, production, every stage of the process is carried out by researchers who act as volunteers, independently of journals for the good of science.

Every single stage of work paid for by the public purse is farmed out, except the profits, which are sucked up by billion-dollar-per-year corporations.

This is routine; it's just the way things work today, a sad hangover from a time when print was a finite resource, even though now it is obsolete in the academic world, replaced by digital documents effortlessly transmitted down the telephone line.

It is a hangover that benefits and enriches a handful of for-profit corporations that create nothing, at the expense of all of humanity's access to the wealth of scientific knowledge.

The costs are real. Just yesterday I met a social worker who - now that she's qualified, now that she's a "professional" - can no longer access the social work journals she needs to do her job because she is no longer at a university, so now she no longer has an access code.

The same is true for doctors, psychologists, neurologists, engineers, botanists, geneticists, chemists, and philosophers around the developing world.

Ultimately, the first publisher I approached with the story, who after a brief discussion I sent the complete 2,000-word report, published a cut down and cobbled together version of the story behind my back.

I panicked and decided as a last-ditch resort to publish my working copy on my blog.

I wanted an accurate and complete version of events not just to be the story of record, but also to be the breaking story, the story that people actually read. Thankfully it was.

The story was accurate, but to my shame the story was incomplete. Since last week I have received countless messages asking me why one name was missing from the report.

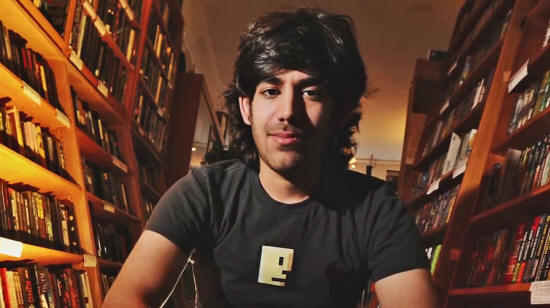

That name was Aaron Swartz.

What follows is the missing chapter...

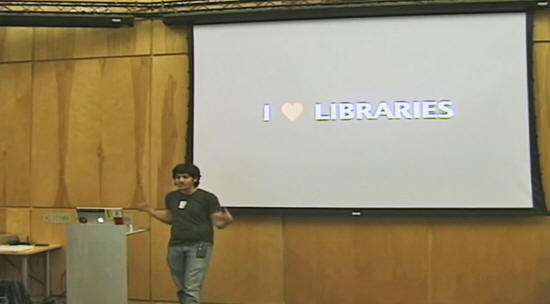

At the very same time that Alexandra was building Sci-Hub, on the other side of the world, a young man named Aaron Swartz was fighting the same fight, in a very different way.

Unlike Alexandra who has explained her reasoning for breaking the law to the judge acting in her case in the frankest possible terms, Aaron always followed the law meticulously.

Aaron was a boy genius:

If Aaron had not invented RSS, then I probably wouldn't have been able to start out independently building my own audience, get noticed, and become a writer.

Without Aaron you almost certainly would not be reading this now.

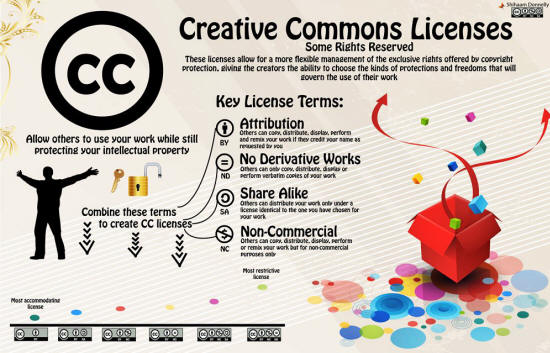

Later, he co-founded Creative Commons, the framework now used by millions of artists, writers, and publishers to free their work of the shackles of copyright with simple, clear open-access licenses.

Billions of pieces of work are now shared using this method. He also co-founded Reddit, a democratic social network that has become "the front page of the Internet," delivering millions of people in any given moment to the most up-voted piece of information in their chosen networks.

He went on to build Deaddrop, now called SecureDrop, a method now broadly used by news agencies to collect information from anonymous sources.

He also built Open Library, a website with the goal of having a page dedicated to every book in existence. In 26 short years Aaron helped found countless organizations dedicated to freedom of information and democratic social progress.

One of those organizations, Demand Progress, has been responsible for some of the largest successful grassroots political campaigns in U.S. history.

Despite earning millions at a very young age from his creations, he was a passionate fighter against wealth disparity:

Aaron soon realized a grand injustice existed in the U.S.

Access to vast swathes of the core documents that make up the law are not freely available to the public.

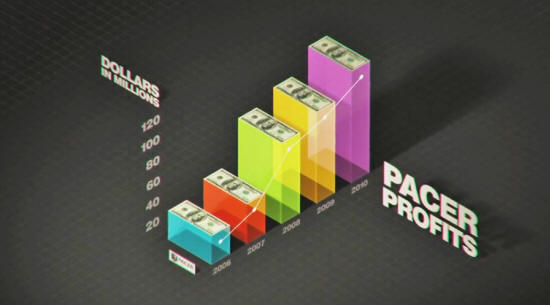

To access the law, you had to pay a complex bureaucratic website 10 cents per page. In fact, you still do, and it's a $10 billion-per-year business.

Of course, the law itself is not copyrighted...

So when in 2008 Aaron wrote a piece of code to download 2.7 million documents from the PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) database through a library terminal, and then made them freely available, Aaron was not technically breaking the law, as the FBI eventually conceded.

Technologist Carl Malamud explains:

At the time Aaron made the documents available to the public there were only 17 libraries capable of freely accessing the law within the entire United States; that's one access point for every 221,090 square miles (572,620 square km) of U.S. soil.

In an unconnected hack, while at Stanford University Aaron downloaded the entire contents of the Westlaw legal database, a database he never publicly released, because that would have been illegal.

Analysis of the data Aaron obtained published in the Stanford Law Review revealed a pattern of massively corrupt practices involving top-level law professors being quietly paid by oil giants and other multi-billion dollar corporations, for the publication of biased legal opinions - "vanity research" purpose-built to be used to argue in court for the minimization of punitive damages in existing multi-million dollar lawsuits.

I could go on about his many and varied achievements.

I could go on about the incalculable good Aaron did for society. I could go on about the steps Aaron always took to act within the law, while he worked on its precipice, always for the betterment of others.

I could go on about how while being in prime position to make untold millions more out of his creations, he lived modestly and spent night and day donating his time to fighting within the law for what is right, but it's not what Aaron created that this story is about; it is what was taken from him, and with him, from all of us.

At the end of 2010, Aaron plugged a laptop directly into the server farm at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

He'd written a Python script called "Keep Grabbing That Pie" to quietly download the entire contents of the JSTOR database of academic research.

Aaron had complete legal access to the research he downloaded, through his university subscription.

His crime, had Aaron ever made it to the dock, would essentially have been taking too many books out of the library.

To their credit, when Aaron was caught, JSTOR chose not to press charges, but in a highly unusual legal decision, Aaron was set upon by the United States government with a string of 13 wire fraud-related felony charges.

On the 6th of January 2011, Aaron was arrested, allegedly assaulted by the police and placed in solitary confinement.

In a strongly worded statement intended to send a message to hackers, federal prosecutors announced Aaron was facing felony charges that would result in up to 35 years in jail, restitution, asset forfeiture and up to a million dollar fine. He was released on $100,000 bail.

The government gave Aaron a non-negotiable demand that he accept the felony charges.

Determined he had not committed a crime, he refused to plead guilty in return for a reduced sentence, and bans and restrictions on his computer use.

This despite the fact that his legal costs had completely exhausted his financial resources and all the money that had been raised to defend him, a sum that ran into the millions of dollars.

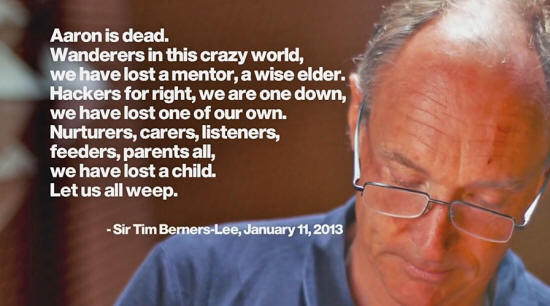

On the 11th January 2013, two years of bitter legal proceedings later, and only two days after the prosecution had declined his counteroffer to a plea deal, he was found hanging dead in his apartment.

Aaron's obituary was the first obituary I ever wrote.

It doesn't do justice to one of the greatest minds of our generation. It was written in a haze of shock, anger, and sadness the day of Aaron's death. I wasn't alone. An earthquake of grief reverberated around the Internet.

His eulogy was read by Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web.

I never knew Aaron, but I am acutely aware of exactly how much I have benefited from his work, and how much we all stand to gain from the work he was doing.

I studied at a university that couldn't afford most useful journals, so I was dependent on the goodwill of others getting me the research I needed to pass.

When I started out writing my first blog, Creative Commons gave me vast and easy access to sources of imagery I could legally and freely use to help illustrate my work; Reddit helped people find my writing even though they were mostly on the other side of the Atlantic. RSS let people that liked my work follow me without spending a penny, enabling me to build a career.

For all of that, I will always be grateful to Aaron.

Aaron died before he could finish his work, but unbeknownst to him, Alexandra had already picked up the baton where he and countless others in online communities dedicated to freedom of information left off.

Alexandra has not only matched the 4 million articles Aaron downloaded from JSTOR before he was caught, but also released the articles into the public domain along with 43 million more, and built Sci-Hub, a one-click instant pay-wall workaround that works not just on JSTOR, but also Elsevier and a whole host of other pay-walled academic publishers.

If I were a religious man, I might say that we can only pray that Alexandra won't face a fate similar to Aaron's - that she will stay safe from prison and legal intimidation and those who wish she would disappear, that she can continue doing what she does best, making discoveries and creating things.

But to say this would be a lie. We can't only pray.

We can do everything in our power to make sure the politicians we elect don't allow corporations to throw the book at researchers who have no other way to conduct science than to share their work freely.

We can't allow politicians to throw away the keys to the libraries.

We must convince academics to stop handing the keys to their work to gang masters who would happily see all of our scientific knowledge remain inaccessible to the vast majority of humanity.

In the words of Aaron himself:

Below is a gripping, thought-provoking and tear-jerking documentary on the events that led to Aaron's death.

It received a string of offers when it was nominated at Sundance, but in the spirit of Aaron's beliefs the film's producers have made it publicly available under a Creative Commons license, so you can watch it in full below.

It's the most moving film I've seen in years.

At the time of Aaron's arrest, Alexandra's website was already in operation, but working on opposite sides of the world, the two were unbeknown to each other.

While Alexandra later came to find Aaron's writings inspiring and is working on translating them to Russian, she maintains her greatest inspiration was the countless "inspired people" all around the world who share knowledge in online communities based on their shared belief that knowledge should be free...

|