|

To establish his supremacy on Earth, Marduk proceeded to establish his supremacy in the heavens. A major vehicle to that end was the all-important annual New Year celebration, when the Epic of Creation was read publicly. It was a tradition whose purpose was to acquaint the populace not only with the basic cosmogony and the tale of Evolution and the arrival of the Anunnaki, but also as a way to state and reinstate the basic religious tenets regarding Gods and Men.

The Epic of Creation was thus a useful and powerful vehicle for indoctrination and re indoctrination; and as one of his first acts Marduk instituted one of the greatest forgeries ever: the creation of a Babylonian version of the epic in which the name "Marduk" was substituted for the name "Nibiru." It was thus Marduk, as a celestial God, who had appeared from outer space, battled Tiamat, created the Hammered Out Bracelet (the Asteroid Belt) and Earth of Tiamat's halves, rearranged the Solar System, and became the Great God whose orbit encircles and embraces "as a loop" the orbits of all the other celestial Gods (planets), making them subordinate to Marduk's majesty.

All the ensuing celestial stations, orbits, cycles, and phenomena were thus the masterworks of Marduk: it was he who determined Divine Time by his orbit, Celestial Time by defining the constellations, and Earthly Time by giving Earth its orbital position and tilt. It was he, too, who had deprived Kingu, Tiamat's chief satellite, of its emerging independent orbit and made it a satellite of Earth, the Moon, to wax and wane and usher in the months.

In so rearranging the heavens, Marduk did not forget to settle some personal accounts. In the past Nibiru, as the home planet of the Anunnaki, was the abode of Anu and thus associated with him. Having appropriated Nibiru to himself, Marduk relegated Anu to a lesser planet - the one we call Uranus. Marduk's father, Enki, was originally associated with the Moon; now Marduk gave him the honor of being "number one" planet - the outermost, the one we call Neptune.

To hide the forgery and make it appear as though it was always so, the Babylonian version of the Epic of Creation (called Enuma elish after its opening words) employed Sumerian terminology for the planetary names, calling the planet NUDIMMUD, "The Artful Creator" - which was exactly what Enki's Egyptian epithet, Khnum, had meant. A celestial counterpart was needed for Marduk's son Nabu.

To achieve that, the planet we call Mercury, which was associated with Enlil's young son Ishkur/Adad, was expropriated and allocated to Nabu. Sarpanit, Marduk's spouse to whom he owed his release from the Great Pyramid and the commutation of the sentence of being buried alive in it to that of exile (the first one of the two), was also not forgotten. Settling accounts with Inanna/Ishtar, he deprived her of the celestial association with the planet we call Venus and granted the planet to Sarpanit.

(As it happened, while the switch from Adad to Nabu was partly retained in Babylonian astronomy, that of replacing Ishtar by Sarpanit did not take hold.)

Enlil was too omnipotent to be shoved aside, instead of changing Enlil's celestial position (as the God of the Seventh Planet, Earth) Marduk appropriated to himself the Rank of Fifty that was Enlil's rank, just a rung below Anu's sixty (Enki's numerical rank was forty). That takeover was incorporated into the Enuma elish by listing, in the seventh and last tablet of the epic, the Fifty Names of Marduk.

Starting with his own name, "Marduk," and ending with his new celestial name, "Nibiru," the list accompanied each name-epithet with a laudatory explanation of its meaning. When the reading of the fifty names during the New Year celebrations was completed, there was no achievement, creative deed, benevolence, lordship, or supremacy left out... "With the Fifty Names," the last two verses of the epic stated, "the Great Gods proclaimed him; with the title Fifty they made him supreme."

An epilogue, added by the priestly scribe, made the Fifty Names required reading in Babylon:

Marduk's seizure of the supremacy in the heavens was accompanied by a parallel religious change on Earth. The other Gods, the Anunnaki leaders - -even his direct adversaries - were neither punished nor eliminated. Rather, they were declared subordinate to Marduk through the gimmick of asserting that their various attributes and powers were transferred to Marduk.

If Ninurta was known as the God of husbandry, who had given Mankind agriculture by damming the mountain gushes and digging irrigation canals - the function now belonged to Marduk. If Adad was the God of rains and storms, Marduk was now the "Adad of rains."

The list, only partially extant on a Babylonian tablet, began as follows:

Some scholars have speculated that in this concentration of all divine powers and functions in one hand, Marduk had introduced the concept of one omnipotent God - a step toward the monotheism of the biblical Prophets. But that confuses the belief in one God Almighty with a religion in which one God is just superior to the other Gods, a polytheism in which one God dominates the others. In the words of Enuma elish, Marduk became "the Enlil of the Gods," their "Lord."

No longer residing in Egypt, Marduk/Ra became Amen, "The Unseen One." Egyptian hymns to him, nevertheless, proclaimed his supremacy, also connoting the new theology that he was now the "God of Gods," "more powerful of might than the other Gods." In one set of such hymns, composed in Thebes and discovered written on what is known as the Leiden Papyrus, the chapters begin with a description of how after the "islands which are in the midst of the Mediterranean" recognized his name as "high and mighty and powerful," the peoples of "the hill countries came down to thee in wonder; every rebellious country was filled of thy terror."

Listing other lands that switched their obedience to Amen-Ra, the sixth chapter continued by de-scribing the God's arrival in the Land of the Gods - as we understand it, Mesopotamia - and the ensuing construction there of Amon's new temple - as we understand it, the Esagil. The text reads almost like that of Gudea's description of all the rare building materials brought over from lands near and far:

Every land, every people, send propitiatory offerings. But not only people pay Amen homage; so do all the other Gods. Here are some of the verses from the following chapters of the papyrus extolling Amen-Ra as the king of the Gods: The company of the Gods which came forth from heaven assembled at thy sight, announcing:

Ingeniously, the policy was not to eliminate the other Great Anunnaki but to control and supervise them. When, in time, the Esagila sacred precinct was built with appropriate grandeur, Marduk invited the other leading deities to come and reside in Babylon, in special shrines that were built for each one of them within the precinct.

The sixth tablet of the epic in its Babylonian version states that after Marduk's own temple-abode was completed, and shrines for the other Anunnaki were erected, Marduk invited all of them to a banquet. "This is Babylon, the place that is your home!" he said. "Make merry in its precincts, occupy its broad places."

By acceding to his invitation, the others would literally have made Babylon what its name - Babili - had meant: "Gateway of the Gods." According to this Babylonian version, the other Gods took their seats in front of the lofty dais on which Marduk had seated himself. Among them were "the seven Gods of des tiny." After the banqueting and the performance of all the rites, after verifying "that the norms had been fixed ac-cording to all the portents,"

Recognizing the symbolic declaration of "peaceful coexistence" by the leader of the Enlilites, Enki spoke up:

Enumerating all the worshiping duties that the people were to perform in honor of Marduk and the other Gods gathered in Babylon, Enki had this to say to the other Anunnaki:

Proclaiming his Fifty Names - granting Marduk the Rank of Fifty that had been Enlil's and Ninurta's - Marduk became the God of Gods. Not a sole God, but the God to whom the other Gods had to pay obeisance. If the new religion proclaimed in Babylon was a far cry from a monotheistic theology, scholars (especially at the turn of this century) wondered and heatedly debated the extent to which the notion of a Trinity had originated in Babylon.

It was recognized that Babylon's New Religion stressed the lineage Enki-Marduk-Nabu and that the divinity of the Son was obtained from a Holy Father.

It was pointed out that Enki referred to him as "our Son," that his very name, MAR.DUK, meant

The fact that all those leading Assyriologists were German was primarily due to the particular interest that the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft - an archaeological society that also served the political and intelligence-gathering ends of Ger-many - had conducted an unbroken chain of excavations at Babylon from 1899 until almost the end of World War 1 when Iraq fell to the British in 1917.

The unearthing of ancient Babylon (though the remains were by and large those from the seventh century BC.) amid the growing realization that the biblical creation tales were of Mesopotamian origin, led to heated scholarly debates under the theme Babel und Bibel - Babylon and Bible, and then to theological ones.

Was Marduk Urtyp Christie? studies (as one so titled by Witold Paulus) asked, after the tale of Marduk's entombment and subsequent reappearance to become the dominant deity was discovered. The issue, never resolved, was just let evaporate as postWorld War I Europe, and especially Germany, faced more pressing problems. What is certain is that the New Age that Marduk and Babylon ushered in circa 2000 BC. manifested itself in a new religion, a polytheism in which one God dominated all the others. Reviewing four millennia of Mesopotamian religion.

Thorkild Jacobsen (The Treasures of Darkness) identified as the main change at the beginning of the second millennium BC. the emergence of national Gods in lieu of the universal Gods of the preceding two millennia. The previous plurality of the divine powers, Jacobsen wrote, "required the ability to distinguish, evaluate and choose" not just between the Gods but also between good and evil.

By assuming all the other Gods' powers, Marduk abolished such choices. "The national character of Marduk," Jacobsen wrote (in a study titled Toward the Image of Tammuz), created a situation in which "religion and politics became more inextricably linked" and in which the Gods, "through signs and omens, actively guided the policies of their countries." The emergence of guiding politics and religion by "signs and omens" was indeed a major innovation of the New Age.

It

was not a surprising development in view of the importance that

celestial signs and omens had played in determining the true

beginning of the zodiacal change and in deciding who would become

supreme on Earth. For many millennia it was the word of the Seven

Who Determine the Destinies, Anu, Enlil, and the other Anunnaki

leaders, who made the decisions affecting the Anunnaki; Enlil, by

himself, was the Lord of the Command as far as Mankind was

concerned. Now, signs and omens in the heavens guided the decisions.

Babylonian texts, and those of neighboring nations in the second and first millennia BC., are replete with such Omina and their interpretation. A whole science, if one so wishes to call it, developed as time went on, with special beru (best translated "fortune teller") priests on hand to interpret observations of celestial phenomena. At first the predictions, continuing the trend that began at the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur, concerned themselves with affairs of state - the fate of the king and his dynasty and the fortunes of the land:

The "entrances" of planets into the zodiacal constellations were thought of as particularly important, as signs of the enhancement of the planet's (good or bad) influence.

The positions of the planets inside the zodiacal constellations were described by the term Manzallu ("stations"), from which the Hebrew plural Mazzaloth (II Kings 23:5) comes, and from which a Mazal ("luck, fortune") evolved, capable of being good luck or bad luck. Since not only constellations and planets but also months had been associated with various Gods - some, by Babylonian times, adversaries of Marduk - the time of the ce-lestial phenomena grew in importance.

One omen, as an example, said: "If the Moon shall be eclipsed in the month Ayaru in the third watch" and certain other planets will be at given positions, "the king of Elam will fall by his own sword ... his son will not take the throne; the throne of Elam will be unoccupied."

A Babylonian text on a very large tablet (VAT-10564) divided into twelve columns contained instructions for what may or may not be done in certain months: "A king may build a temple or repair a holy place only in Shebat and Adar ... A person may return to his home in Nissan." The text, called by S. Langdon (Babylonian Menologies and the Semitic Calendars) "the great Babylonian Church Calen-dar," then listed the lucky and unlucky months, even days and even half days, for many personal activities (such as the most favorable time for bringing a new bride into the house).

As the omens, predictions, and instructions increasingly assumed a more personal nature, they verged on the horoscopic. Would a certain person, not necessarily the king, recover from an illness? Will the pregnant mother bear a healthy child? If some times or certain omens were unlucky, how could one ward off the ill luck? In time, incantations were devised for the purpose; one text, for example, actually provided the sayings to be recited to prevent the thinning of a man's beard by appealing to "the star that giveth light" with prescribed utterings.

All that was followed by the introduction of amulets in which the warding-off verses were Aftermath 359 inscribed. In time, too, the material of the amulet (mostly made to be worn on a string around the neck) could also make a difference. If made of hematite, one set of instructions stated, "the man could lose that which he acquired." On the other hand, an amulet made of lapis lazuli assured that "he shall have power."

In the famous library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, archaeologists have found more than two thousand clay tablets with texts pertaining to omens. While the majority dealt with celestial phenomena, not all of them did so. Some dealt with dream-omens, others with the interpretation of "oil and water" signs (the pattern made by oil as it was poured on water), even the significance of animal entrails as they appeared after sacrifices.

What used to be astronomy became astrology, and astrology was followed by divinations, fortune-telling, sorcery. R. Camblell Thompson was probably right in titling a major collection of omen texts The Reports of the Magicians and Astrologers of Nineveh and Babylon. Why did the New Age bring all that about? Beatrice Goff (Symbols of Prehistoric Mesopotamia) identified the cause as the breakdown of the Gods-priests-kings framework that had held society together in the prior millennia.

Astronomy became astrology because, with the Olden Gods gone from their "cult centers," the people were looking at least for signs and omens to guide them in turbulent times. Indeed, even astronomy itself was no longer what it had been during two millennia of Sumerian achievements. Despite the reputation and high esteem in which "Chaldean" astronomy was held by the Greeks in the second half of the first millennium BC., it was a sterile astronomy and a far cry from that of Sumer, where so many of the principles, methods, and concepts on which modern astronomy is founded had originated.

O. Neugebauer wrote in The Exact Sciences in Antiquity.

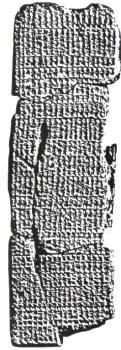

That "mathematical theory," studies of the astronomical tablets of the Babylonians revealed, were column upon column upon column of rows of numbers, imprinted - we use the term purposely - on clay tablets as though they were computer printouts! Fig. 161 is a photograph of one such (fragmented) tablet; Fig. 162 is the contents of such a tablet converted to modern numerals. Not unlike the astronomical codices of the Mayas, that contained page after page after page of glyphs dealing with the planet Venus, but without any indication that they were based on actual Mayan observations but rather followed some data source, so were the Babylonian lists of predicted positions of the Sun, Moon, and visible planets extremely detailed and accurate. Figure 161 Figure 162

In the Babylonian instance, however, the position lists (called "Ephemerides") were accompanied by procedure texts on companion tablets in which the rules for computing the ephemerides were given step by step; they contained instructions how, for example, to compute - for over fifty years in advance - Moon eclipses by taking into account data from columns dealing with the orbital velocities of the Sun and the Moon and other factors that were needed.

But, to quote from Astronomical Cuneiform Texts by O. Neugebauer, "unfortunately these procedure texts do not contain much of what we would call the 'theory' behind the method." Yet "such a theory," he pointed out, "must have existed because it is impossible to devise computational schemes of high complication without a very elaborate plan.''

It was clear from the very neat script and carefully arranged columns and rows, Neugebauer stated, that these Babylonian tablets were copies meticulously made from preexisting sources already so neatly and accurately arranged. The mathematics on which the number series were based was the Sumerian sexagesimal system, and the terminology used - of zodiacal constellations, month names, and more than fifty astronomical terms - was purely Sumerian. There can, therefore, be no doubt that the source of the Babylonian data was Sumerian; all the Babylonians knew was how to use them, by translating into Babylonian the Sumerian "procedure texts."

It was not until the eighth or seventh centuries BC. that astronomy, in what is called the Neo-Babylonian period, reassumed the observational aspects. These were recorded in what scholars (e.g., A.J. Sachs and H. Hunger, Astronomical Diaries and Related Texts from Babylonia) call "astronomers' diaries."

They believe that Hellenistic, Per-sian, and Indian astronomy and astrology derived from such records. The decline and deterioration manifested in astronomy was symptomatic of an overall decline and regression in the sciences, the arts, the laws, the social framework. One is hard put to find a Babylonian "first," contributed to culture and civilization, that surpassed, or even matched, the countless Sumcrian ones.

The sexagesimal system and the mathematical theories were retained without improvement. Medicine deteriorated to become little more than sorcery. No wonder that many of the scholars studying the period consider the time when the Old Age of the Sumerian Bull of Heaven gave way to the New Age of the Babylonian Ram a "time of darkness." The Babylonians, as did the Assyrians and others that followed, retained - almost until the Greek era - the cuneiform script that the Sumerians had devised (based, as we have shown in Genesis Revisited, on sophisticated geometric and mathematical theories).

But instead of any improvement, the Old Babylonian tablets were written in a more scribbled and less refined script. The many Sumerian references to schools, teachers, homework, were nonexistent in the ensuing centuries. Gone was the Sumerian tradition of literary creativity that bequeathed to future generations, including ours, "wisdom" texts, poetry, proverbs, allegorical tales, and not least of all the "myths" that had provided the data concerning the solar system, the Heavens and Earth, the Anunnaki, the creation of Man.

These, it ought to be pointed out, were literary genres that reappear only in the Hebrew Bible about a millennium later. A century and a half of digging up the remains of Babylon produced texts and inscriptions by rulers boasting of military campaigns and conquests, of how many prisoners were taken or heads cut off - whereas Sumerian kings (as, for example, Gudea) boasted in their inscriptions of building temples, digging canals, having beautiful works of art made. A harshness and a coarseness replaced the former compassion and elegance.

The Babylonian king Hammurabi, the sixth in what is called the First Dynasty of Babylon, has been renowned because of his famous legal code, the "Code of Hammurabi." It was, however, just a listing of crimes and their punishments - whereas a thousand years earlier Sumerian kings had promulgated codes of social justice, their laws protecting the widow, the orphan, the weak, and decreeing that "you shall not take away the donkey of a widow," or "you shall not delay the wages of a day laborer."

Again, the Sumerian concept of laws, in-tended to direct human conduct rather than punish its faults, reappears only in the biblical Ten Commandments some six centuries after the fall of Sumer. Sumerian rulers cherished the title EN.SI - "Righteous Shepherd." The ruler selected by lnanna to reign in Agade (Akkad) whom we call Sargon I in fact bore the name-epithet Sharru-kin, "Righteous King."

The Babylonian kings (and the Assyrian ones later on) called themselves "King of the four regions" and boasted of being "King of kings" rather than a "shepherd" of the people. (It was greatly symbolic that Judea's greatest king, David, had been a shepherd.) Missing in the New Age were expressions of tender love. This may sound like an insignificant item in the long list of changes for the worse; but we believe that it was a manifestation of a profound mind-set that went all the way down from the top - from Marduk himself.

The poetry of Sumer included a substantial number of love and lovemaking poems. Some, it is true, were related to Inanna/Ishtar and her relationship with her bridegroom Dumuzi. Others were recited or sung by kings to divine spouses. Yet others were devoted to the common bride and bridegroom, or husband and wife, or parental love and compassion. (Once again, this genre reappears only after many centuries in the Hebrew Bible, in the Book of The Song of Songs.)

It seems to us that this omission in Babylonia was not accidental, but part of an overall decline in the role of women and their status as compared to Sumerian times. The remarkable role of women in all walks of life in Sumer and Akkad and its very marked downgrading upon the rise of Babylon, have been lately reviewed and documented in special studies and several international conferences, such as the "Invited Lectures on the Middle East at the University of Texas at Austin" published in 1976 (The Legacy of Sumer) by Denise Schmandt-Besserat as editor, and the proceedings at the 33rd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale in 1986, whose theme was "The woman in the ancient Near East."

The gathered evidence shows that in Sumer and Akkad women engaged not only in household Aftermath 365 chores like spinning, weaving, milking, or tending to the family and the home, but also were "working professionals" as doctors, midwives, nurses, governesses, teachers, beauticians, and hairdressers. The textual evidence recently culled from discovered tablets augments the depictions of women in their varied tasks from the earliest recorded times that showed them as singers and musicians, dancers and banquet-masters.

Women were also prominent in business and property management. Records have been found of women managing the family lands and overseeing their cultivation, and then supervising the trade in the resulting products. This was especially true of the "ruling families" of the royal court. Royal wives administered temples and vast estates, royal daughters served not only as priestesses (of which there were three classes) but even as the High Priestess.

We have already mentioned Enheduanna, the daughter of Sargon I, who composed a series of memorable hymns to Sumer's great ziggurat-temples. She served as High Priestess at Nannar's temple in Ur (Sir Leonard Woolley, who had excavated at Ur, found there a round plaque depicting Enheduanna performing a libation ceremony).

We know that the mother of Gudea, Gatumdu, was a High Priestess in the Girsu of Lagash. Throughout Sumerian history, other women held such high positions in the temples and priestly hierarchies. There is no record of a comparable situation in Babylon. The story of women's role and position in the royal courts was no different. One must refer to Greek sources to find mention of a ruling queen (as distinct from a queen-consort) in Babylonian history - the tale of the legendary Semiramis who, according to Herodotus (I, 184) "held the throne in Babylon" in earlier times. Scholars have been able to establish that she was a historical person, Shammu-ramat.

She did

reign in Babylon, but only because her husband, the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad, had captured the city in 811 BC. She served as the

royal regent for five years after her husband's death, until their

son Adad-Nirari III could assume the throne. 'This lady,'1

Her name was Ku-Baba; she is recorded in the Sumerian King

Lists as "the one who consolidated the foundations of Kish'' and

headed the Third Dynasty of Kish. There may have been other queens

like her during the Sumerian era, but scholars are not certain of

their status (i.e. whether they were only queen-consorts or regents

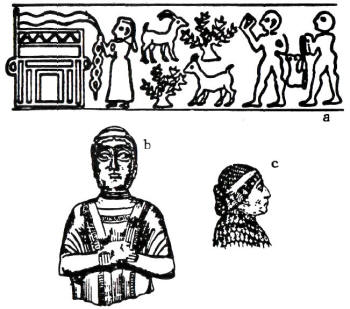

for an underage son). Figures 163a, 163b, and 163c

Scholars

researching these aspects of the civilizations of the ancient Near

East have noted that whereas during the two millennia of Sumerian

primacy women were depicted by themselves in drawings and in plastic

art - hundreds of statues and statuettes that are actual portraits of

individual females have been found - there is an almost total absence

of such depictions in the post-Sumerian period in the Babylonian

empire.

In the Sumerian pantheon, female Anunnaki played leading roles along with the males from the very beginning. If EN.LIL was "Lord of the Command," his spouse was NIN.LIL, "Lady of the Command"; if EN.KI was "Lord of Earth," his spouse was NIN.KI, "Lady of Earth." When Enki created the Primitive Worker through genetic engineering, Ninharsag was there to be the cocreator.

Suffice it to reread the inscriptions of Gudea to realize how many important roles Goddesses played in the process that led to the building of the new ziggurat-temple. Suffice it also to point out that one of Marduk's first acts was to transfer to the male Nabu the functions of Nisaba as deity of writing. In fact, all those Goddesses that in the Sumerian pantheon held specific knowledge or performed specific functions, were by and large relegated to obscurity in the Babylonian pantheon. When Goddesses were mentioned, they were only listed as spouses of the male Gods.

The same held true for the people under the Gods: women were mentioned as wives or daughters, mostly when they were "given" in arranged marriages. We surmise that the situation reflected Marduk's own bias. Ninharsag, the "Mother of Gods and men," was, after 368 WHEN TIME BEGAN all, the mother of his main adversary in the contest for the supremacy on Earth, Ninurta.

Inanna/Ishtar was the one who had caused him to be buried alive inside the Great Pyramid. The many Goddesses who were in charge of the arts and sciences assisted the construction of the Eninnu in Lagash as a symbol of defiance of Marduk's claims that his time had come. Was there any reason for him to retain the high position and veneration of all these females? Their down-grading in religion and worship was, we believe, reflected in a general downgrading of the status of women in the post-Sumerian society. An interesting aspect of that was the apparent change in the rules of succession.

The source of the conflict between Enki and Enlil was the fact that while Enki was Anu's firstborn, Enlil was the Legitimate Heir because he was born to Anu by a mother who was Anu's half sister. On Earth, Enki repeatedly tried to have a son by Ninharsag, a half sister of his and Enlil's. but she bore him only female-offspring. Ninurta was the Legitimate Heir on Earth because it was Ninharsag who bore him to Enlil.

Following these rules of succession, it was Isaac who was born to Abraham by his half sister Sarah and not the firstborn Ishmael (the son of the maid Hagar) who became the patriarch's Legitimate Heir. Gilgamesh, king of Erech, was two-thirds (not just one-half) "divine" because his mother was a Goddess; and other Sumerian kings sought to enhance their status by claiming that a Goddess nursed them with mother's milk.

All such matriarchal lineages lost their significance when Marduk became supreme. (Maternal lineage became sig-nificant again among the Jews at the time of the Second Temple.) What was the ancient world experiencing at the beginning of the New Age of the 20th century BC., in the aftermath of international wars, the use of nuclear weapons, the dissolution of a great unifying political and cultural system, the displacement of a boundary-less religion with one of national Gods?

We at the end of the 20th century ad. may find it possible to visualize, having ourselves witnessed the Aftermath 369 aftermath of two world wars, the use of nuclear weapons, the dissolution of a giant political and ideological system, the displacement of centrally controlled and boundless empires by religiously guided nationalism.

The phenomena of millions of war refugees on the one hand, and the rearrangement of the population-map on the other hand, so symptomatic of the events of the twentieth century a.d. had their counterparts in the twentieth century BC. For the first time there appears in Mesopotamian inscriptions the term Munnahtutu, literally meaning "fugitives from a destruction."

In light of our twentieth century a.d. experience a better translation would be "displaced per-sons" - people who, in the words of several scholars, had been "detribalized," people who had lost not only their homes, possessions, and livelihoods but also the countries to which they had belonged and were henceforth "stateless refugees," seeking religious asylum and personal safe havens in other peoples' lands.

As Sumer itself lay prostrate and desolate, the remnants of its people (in the words of Hans Baumann, The Land of Ur) "spread in all directions; Sumerian doctors and astronomers, architects and sculptors, cutters of seals and scribes, became teachers in other lands." To all the many Sumerian "firsts," they have thus added one more as Sumer and its civilization came to a bitter end: the first Diaspora... Their migrations, it is certain, took them to where earlier groups had gone, such as Harran where Mesopotamia links up with Anatolia, the place to where Terah and his family had migrated and which was already then known as "Ur away from Ur."

They undoubtedly stayed (and prospered) there in ensuing centuries, for Abraham sought a bride for Isaac his son among the erstwhile relatives there, and so did Isaac's son Jacob. Their wanderings no doubt also followed in the footsteps of the famed Merchants of Ur, whose loaded caravans and laden ships had blazed trails on land and sea to places near and far.

Indeed, one can learn where the "displaced persons" of Sumer went by looking at the foreign cultures that sprouted one after the other in foreign lands - cultures whose scrip! was the cuneiform, whose language included countless Sumerian "loanwords" (especially in the sciences), whose pantheons, even if the Gods were called by local names, were the Sumerian pantheon, whose "myths" were the Sumerian "myths," whose tales of heroes (such as of Gilgamesh) were of Sumerian heroes. How far did the wanderers of Sumer go?

We know that they certainly went to the lands where new nation-states were formed within two or three centuries after the fall of Sumer. While the Amurru ("Westerners"), followers of Marduk and Nabu, poured into Mesopotamia and provided the rulers that made up the First Dynasty of Marduk's Babylon, other tribes and nations-to-be engaged in massive population movements that forever changed the Near East, Asia, and Europe. They brought about the emergence of Assyria to Babylon's north, the Hittite kingdom to the northwest, the Hurrian Mitanni to the west, the Indo-Aryan kingdoms that spread from the Caucasus on Babylon's northeast and cast, and those of the "Desert peoples" to the south and of the "Sealand people" to the southeast.

As we know from the later records of Assyria, Hatti-land, Elam, Babylon and from their treaties with others (in which each one's national Gods were invoked), the great Gods of Sumer did forgo the "invitation" of Marduk to come and reside within the confines of Babylon's sacred precinct; instead, they mostly became national Gods of the new or old-new nations. It was in such lands that the Sumerian refugees were given asylum all around Mesopotamia, serving at the same time as catalysts for the conversion of their host countries into modern and flourishing states.

But some must have ventured to more distant lands, migrating there on their own or, more probably, accompanying the displaced Gods themselves. To the east there stretched the limitless reaches of Asia. Much discussed has been the migratory wave of the Aryans (or lndo-Aryans as some prefer).

Originating somewhere southwest of the Caspian Sea, they migrated to what had been the Third Region of Ishtar, the Indus Valley, to re-Aftermath 371 populate and reinvigorate it. The Vedic tales of Gods and heroes that they brought with them were the Sumerian "myths" retold; the notions of Time and its measurement and cycles were of Sumerian origin. It is a safe assumption, we believe, that mingled into the Aryan migration were Sumerian refugees; we say "safe assumption" because Sumerians had to pass that way in order to reach the lands that we call the Far East.

It is generally accepted that within two centuries or so of 2000 BC. a "mysteriously abrupt change" (in the words of William Watson, China) had occurred in China; without any gradual development the land was transformed from one of primitive villages to one with "walled cities whose rulers possessed bronze weapons and chariots and the knowledge of writing."

The cause, all agree, was the arrival of migrants from the west - the same "civilizing influences" of Sumer "which can ultimately be traced to the cultural migrations comparable to those which radiated in the West from the Near East" - the migrations in the aftermath of the fall of Sumer.

The "mysteriously abrupt" new civilization blossomed out in China circa 1800 BC. according to most scholars. The vastness of the country and the sparseness of the earliest evidence offer fertile grounds for scholarly disagreements, but the prevalent opinion is that writing was introduced together with Kingship by the Shang Dynasty; the purpose was significant in itself: to record omens on animal bones.

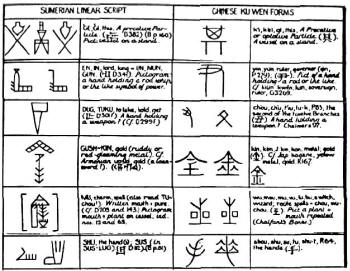

The omens were mostly concerned with inquiries for guidance from enigmatic Ancestors. The writing was monosyllabic and the script was pictographic (from which the familiar Chinese characters evolved into a kind of "cuneiform" - Fig. 164) - both hallmarks of Sumerian writing. Nineteenth-century observations regarding the similarity between the Chinese and Sumerian scripts were the subject of a major study by C.J. Ball (Chinese and Sumerian, 1913) that was published under the auspices of Oxford University. Figure 164

It proved conclusively the similarity between the Sumerian pictographs (from which the cuneiform signs evolved) and the old forms (Ku Wen) of Chinese writing. Ball also tackled the issue of whether this was a similarity stemming only from the expectation that a man or a fish would be drawn pictorially in similar ways even by unrelated cultures.

What his research has shown was that not only did the pictographs look the same, but they also (in a material number of instances) were pronounced the same way; this included such key terms as An for "heaven" and "God," En for "lord" or "chief," Ki for "Earth" or "land," Itu for "month," Mul for "bright/shining" (planet or star). Moreover, when a Sumerian syllable had more than one meaning, the parallel Chinese pictograph had a similar set of varied meanings; Fig. 165 reproduces some of the more than one hundred instances illustrated by Ball. Figure 165

Recent studies in linguistics,

spearheaded by former Soviet scholars, have expanded the Sumerian

link to include the whole family of Central and Far Asian or

"Sino-Tibetan" languages, Such links form only one aspect of a

variety of scientific and "mythological" aspects that recall those

of Sumer. The former are especially strong; such aspects as the

calendar of twelve months, time counting by dividing the day into

twelve double-hours, the adoption of the totally arbitrary device of

the zodiac, and the tradition of astronomical observations are

entirely of Sumerian origin. The "mythological" links are more widespread. Throughout the steppes of Central Asia and all the way from India to China and Japan, the religious beliefs spoke of Gods of Heaven and Earth and of a place called Sumeru where, at the navel of the Earth, there was a bond that connected the Heaven and the Earth as though the two were two pyramids, one inverted atop the other, linked together as an hourglass with a long and narrow waist.

The Japanese Shintu religious belief that their emperor is descended of a son of the Sun becomes plausible if one assumes that the reference is not to the star around which Earth orbits, but to the "Sun God" Utu/Shamash; for with the spaceport in the Sinai of which he had been in charge obliterated, and the Landing Place in Lebanon in Mardukian hands, he may well have wandered with bands of his followers to the far reaches of Asia.

As linguistic and other evidence indicates, the Sumerian Munnahtutu had also gone westward into Europe, using two routes: one through the Caucasus and around the Black Sea, the other via Anatolia. Theories concerning the former route see the Sumerian refugees passing through the area that is now the state of Georgia (in what used to be the Soviet Union), accounting for its people's unusual language which shows affinity to Sumerian, then advancing along the Volga River, establishing its principal city whose ancient name was Samara (it is now called Kuybichev), and - according to some researchers - finally reaching the Baltic Sea.

This would explain why the unusual Finnish language is similar to no other except to Sumerian. (Some also attribute such an origin to the Estonian language.) The other route, where some archaeological evidence supports the linguistic data, sees the Sumerian refugees advancing along the Danube River, thereby corroborating the deep and persistent belief among the Hungarians that their unique language could also have had but one source: Sumerian.

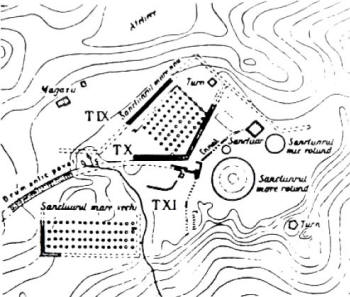

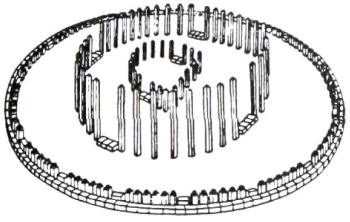

Have Sumerians indeed come this way? The answer might be found in one of the most puzzling relics from antiquity that can be seen where the Danube meets the Black Sea in what was once the Celtic-Roman province of Dacia (now part of Romania). There, at a site called Sarmizegetusa, a series of what researchers have called "calendrical temples" includes what could well be described as "Stonehenge by the Black Sea." Built on several man-made terraces, various structures have been so designed as to form integrated components of a wondrous Time Computer made of stone and wood (Fig. 166). Figure 166

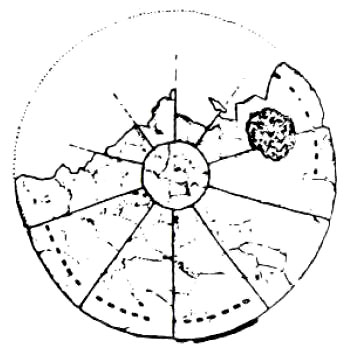

Archaeologists have identified five structures that were in reality rows of round stone "lobes" shaped to form short cylinders, neatly arranged within rectangles formed by sides made of small stones cut to a precise design. The two larger of these rectangular structures contained sixty lobes each, one (the "large old sanctuary") in four rows of fifteen, and the other (the "large new sanctuary") six rows of ten. Three components of this ancient "calendar city" were round. The smallest is a stone disk made of ten segments (Fig. 167) in which small stones were embedded to form a circumference - six stones per segment, making a total of sixty.

Figure 167

The second round structure, sometimes called the "small round sanctuary," consists of a perfect circle of stones, all precisely and identically shaped, arranged in eleven groups of eight, one of seven and one of six; wider and differently shaped stones, thirteen in number, were placed so as to separate the other grouped stones. There must have been other posts or pillars within the circle, for observation and computing; but none can be determined with certainty.

Studies, such as Il Templo-Calendario Dacico di Sarmizegetusa by Hadrian Daicoviciu, suggest that this structure served as a lunar-solar calendar enabling a variety of calculations and forecasts, including the proper intercalation between the solar and lunar years by the periodic addition of a thirteenth month. This and the prevalence of the number sixty, the basic number of the Sumerian sexagesimal system, led researchers to discern strong links to ancient Mesopotamia.

The similarities, H. Daicoviciu wrote, "could have been neither a coincidence nor an accident." Archaeological and ethnographic studies of the area's history and prehistory in general indicate that at the beginning of the second millennium BC. a Bronze Age civilization of "nomadic shepherds with a superior social organization" (Rumania, an official guidebook) arrived in the area that was until then settled by "a population of simple hand-tillers." The time and the description fit the Sumerian migrants.

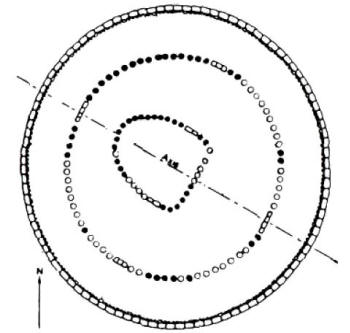

The most impressive and intriguing component of this Calendar City is the third round "temple." It consists of two concentric circles surrounding a "horseshoe" in the middle (Fig. 168), bearing an uncanny similarity to Stonehenge in Britain. The outer circle, some 96 feet in diameter, is made up of a ring of 104 dressed andesite blocks that surrounds 180 perfectly shaped oblong andesite blocks, each with a square peg on top as though all were intended to support a movable marker. Figure 168

These uprights are arranged in groups of six; the groups are separated by perfectly shaped horizontal stones, thirty in all. Altogether, then, the outer circle of 104 stones rings an inner circle of 210 (180 + 30) stones. The second circle, between the outer one and the horseshoe, consists of sixty-eight postholes - akin to the Aubrey holes at Stonehenge - divided into four groups separated by horizontal stone blocks: three each in the northeast and southeast positions and four each in the northwest and southeast positions, giving the "henge" its main northwest-southeast axis and its perpendicular northeast - southwest one.

These four grouped markers, one can readily

notice, emulate the four Station Stones at Stonehenge. Figure 169

Noting that the wooden posts were coated with a terra-cotta "plating," Serban Bobancu and other researchers at the National Academy of Romania (Calendrul de la Sarmizegetusa Regia) observed that each of those posts "had a massive limestone block as its foundation, a fact that undoubtedly reveals the numerical structure of the sanctuary and proves, as in fact all the others structures do, that the builders wished these structures to last throughout centuries and millennia."

These latest researchers concluded that the "old temple" originally consisted of only fifty-two lobes (4x13 rather than the 4 x 15 arrangement) and that there were in effect two calendrical systems geared into one another at Sarmizegetusa: one a solar-lunar calendar with Mesopotamian roots, and another "ritual calendar" geared to fifty-two, akin to the sacred cycle of Mesoamerica and having stellar aspects rather than lunar-solar ones.

They concluded that the "stellar era" consisted of four periods of 520 years each (double the 260 of the Mesoamerican Sacred Calendar), and that the ultimate purpose of the calendrical complex was to measure an "era" of 2,080 years (4 x 520)- - the approximate length of the Age of Aries. Who was the mathematical-astronomical genius who had devised all that, and to what purpose?

The spellbinding answer, we believe, also leads to a solution of the enigmas of Quetzalcoatl and the circular observatories that he had built, the God who according to Mesoamerican lore left at one point in time to go back eastward across the seas (promising to return).

When the Greeks adopted Thoth as their God Hermes, they bestowed on him the title Hermes Trismegistos, "Hermes the thrice greatest."

Perhaps they recognized that he had thrice guided Mankind in the observation of the beginning of a New Age- - the changeover to Taurus, to Aries, to Pisces. For that was, for those generations of Mankind, when Time began.

|