|

The more we know about Stonehenge thanks to modern science, the more incredible Stonehenge becomes. Indeed, were it not for the visible evidence of megaliths and earth works - were they somehow to vanish, as so many ancient monuments did through the vagaries of time and nature or ravages wrought by Man - the whole tale of stones that could compute time and circles that could foretell eclipses and determine the movements of the Sun and the Moon would have sounded so implausible for Stone Age Britain that it would have been considered just a myth.

The great antiquity of Stonehenge, which kept increasing as scientific knowledge about it progressed, is of course what troubles most scientists; and it is primarily the dates of construction ascertained for Stonehenge I and II + III that have led archaeologists to seek Mediterranean visitors, and eminent scholars to allude to ancient gods, as the only possible explanations for the enigma. For of the series of troubling questions, such as by Whom and What for, the When is the most satisfactorily answered. Archaeology and physics (through modern dating methods such as carbon-14 measurements) were joined by archaeoastronotny to agree on the dates: 2900/2800 BC. for Stonehenge I, 2100/2000 BC. for Stonehenge II and III.

The father of the science of archaeoastronomy - though he preferred to call it astroarchaeology, which better conveys what he had in mind - was undoubtedly Sir Norman Lockyer. It is a measure of how long established science takes to accept innovation to note that it is virtually a full century since the publication of Lockyer's masterwork, The Dawn of Astronomy, in 1894.

Having visited the Levant in 1890 he observed that whereas for the early civilizations in India and China there are few monuments but many written records establishing their age, the opposite holds true in Egypt and Babylonia: they were "two civilizations of undefined antiquity" where monuments abounded but the measure of their antiquity was uncertain fat the time of Lockyer's writing).

It struck him, he wrote, that it was truly remarkable that in Babylonia "from the beginning of things the sign for God was a star" and that likewise in Egypt, in the hieroglyphic texts, three stars represented the plural term "gods." Babylonian records on clay tablets and burned clay bricks, he noted, appeared to deal with regular cycles of "moon and planet positions with extreme accuracy." Planets, stars, and the constellations of the zodiac are rep resented on the walls of Egyptian tombs and on papyruses.

In the Hindu pantheon, he observed, we find the worship of the Sun and of the Dawn: the name of the god Indra meaning "The Day Brought by the Sun" and that of the goddess Ushas meaning "Dawn." Can astronomy be of assistance to Egyptology? he wondered; can it help define the measure of Egyptian and Babylonian antiquity? When one considers the Hindu Rigveda and Egyptian inscriptions from an astronomical point of view, Lockyer wrote,

The horizon, he pointed out, is "the place where the circle which bounds our view of Earth's surface and the sky appear to meet." A circle, in other words, where Heaven and Earth touch and meet. It is there that the ancient peoples sought whatever sign or omen their observers were looking for.

Since the most regular phenomenon observable on the horizon was the rising and setting of the Sun on a daily basis, it was natural to make this the basis of ancient astronomical observations, and to relate other phenomena (such as the appearance or movements of planets and even stars) to their "heliacal rising," their brief appearance on the eastern horizon as the turning Earth reaches the few moments of dawn, when the Sun begins to rise but the sky is dark enough to see the stars. An ancient observer could easily determine that the Sun always rises in the eastern skies and sets in the western skies, but he would have noted that in summer the Sun appears to rise in a higher arc than in winter and the days are longer.

This, modern astronomy explains, is due to the fact that the Earth's axis around which it rotates daily is not perpendicular to its path around the Sun (the Ecliptic) but is inclined to it - about 23.5 degrees nowadays. This creates the seasons and the four points in the seeming movement of the Sun up and down in the skies: the summer and winter solstices and the spring ("vernal") and autumnal equinoxes (which we have described earlier). Studying the orientation of temples old and not so old, Lockyer found that those he called "Sun Temples" were of two kinds: those oriented according to the equinoxes and those oriented according to the solstices.

Though the Sun always rises in the eastern skies and sets in the western skies, it is only on the days of the equinoxes that it rises anywhere on Earth precisely in the east and sets precisely in the west, and Lockyer therefore deemed such "equinoctial" temples to be more universal than those whose axis was oriented according to the solstices; because the angle formed by the northern and southern (to an observer in the northern hemisphere, the summer and winter) solstices de-pended on where the observer was - his latitude. Therefore, "solstitial" temples were more individual, specific to their geographic location (and even elevation).

As examples of equinoctial temples Lockyer cited the Temple to Zeus at Baalbek, the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, and the great basilica of St. Peter's in the Vatican in Rome (Fig. 13) - all oriented on a precise east-west axis. Regarding the latter he quoted studies on church architecture that described how at the Old St. Peter's (begun under Constantine in the fourth century and torn down early in the sixteenth century), on the day of the vernal equinox,

Figure 13

Lockyer added that "the present church fulfils the same conditions." As examples of "solstitial" Sun Temples Lockyer described the principal Chinese "Temple of Heaven" in Peking, where "the most important of all state observances in China, the sacrifice performed in the open air at the south altar of the Temple of Heaven," was held on the day of the winter solstice, December 21; and the structure at Stonehenge, oriented to the summer solstice. All that was, however, just a prelude to Lockyer's main studies, in Egypt.

Studying the orientation of Egypt's ancient temples, Lockyer concluded that the older ones were "equinoctial" and the later ones "solstitial." He was amazed to discover that earlier temples revealed greater astronomical sophistication than later ones, for they were intended to observe and venerate not only the rising or setting of the Sun, but also of stars. Moreover, the earliest shrine suggested a mixed Sun-Moon worship that shifted to an equinoctial, i.e. Sun, focus.

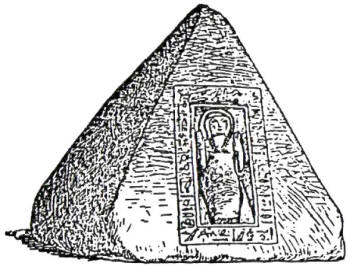

That equinoctial shrine, he wrote, was the temple in Heliopolis ("City of the Sun" in Greek) whose Egyptian name, Annu, was also mentioned in the Bible as On. Lockyer calculated that the combination of solar observations with the period of the bright star Sirius and with the annual rising of the Nile, a triple conjunction on which the Egyptian calendar was based, indicated that in Egyptian time reckoning Point Zero was circa 3200 BC. The Annu shrine, it is known from Egyptian inscriptions, held the Ben-Ben ("Pyramidion-Bird"), claimed to have been the actual conical upper part of the "Celestial Barge" in which the god Ra had come to Earth from the "Planet of Millions of Years."

This object, usually kept in the temple's inner sanctum, was put on public display once a year, and pilgrimages to the shrine to view and venerate the sacred object continued into dynastic times. The object itself has vanished over the millennia; but a stone replica thereof has been found, showing the great god visible through the doorway or hatch of the capsule (Fig. 14).

The legend of the Phoenix, the mythical bird that dies and resurrects after a certain period, has also been traced to this shrine and its veneration on the first day of the Egyptian calendar - the first day of the first month which was named the Month of Thoth. Fig. 14

In other words, the Sed festival was a kind of New Year's Day festival celebrated not each year but after the passage of a number of years. The presence of both equinoctial and solstitial orientations in this temple implies familiarity - in the third millennium BC. - -with the concept of the Four Corners. Drawings and inscriptions found in the temple's corridor describe the king's "sacred dance."

They were copied, translated, and published by Ludwig Borchardt with H. Kees and Friedrich von Bissing in Das Re-Heiligtum des Konigs Ne-Woser-Re. They concluded that the "dance" represented the "cycle of sanctification of the four corners of the Earth." The equinoctial orientation of the temple proper and the solstitial one of the corridor, bespeaking the movements of the Sun, led Egyptologists to apply to the structure the term "Sun Temple."

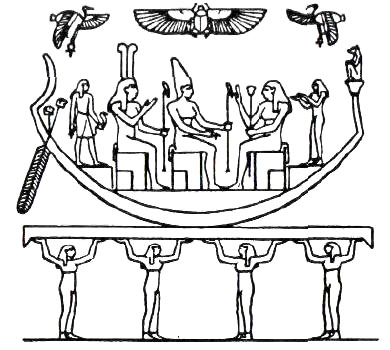

They found reinforcement in this designation in the discovery of a "solar boat" (partly carved out of the rock and partly built of dried and painted bricks) buried under the sands just south of the temple enclosure. Hieroglyphic texts dealing with the measurement of time and the calendar in ancient Egypt held that the celestial bodies traversed the skies in boats. Often, the gods or even the deified pharaohs (having joined the gods in the Afterlife) were depicted in such boats, sailing above the firmament of the skies that was held up at the four corner points (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17

The next great temple clearly emulated the pyramidion-platform concept (Fig. 18) of the Ne-User-Ra "Sun Temple"; but it was already fully oriented to the solstices from its inception, having been planned and executed along a northwest - southeast axis.

It was built on the west side of the Nile (near the present-day village of Deir-el-Bahari) in Upper Egypt, as part of greater Thebes, by the Pharaoh Mentuhotep I circa 2100 BC. Six centuries later Tuthmosis III and Queen Hatshepsut of the XVIII dynasty added their temples there; the orientation was similar - but not exactly so (Fig. 19).

Figure 18

Figure 19

It was at Thebes (Karnak) that Lockyer made his most important discovery, one that laid the foundation for archaeoastronomy. The sequence of chapters, facts, and arguments in The Dawn of Astronomy reveals that Lockyer's route to Karnak and Egyptian temples passed through the European evidence.

There was the orientation of the Old St. Peter's in Rome and the information about the beam of sunlight at the spring equinox sunrise; and there was St. Peter's Square (a woodcut drawing of which Lockyer included, (Fig. 20) with its startling similarities to Stonehenge...

Figure 20

He looked at the Parthenon in Athens, Greece's principal shrine (Fig. 21) and found that,

He had in front of him drawings of the layout plans of various Egyptian temples where orientations seemed to vary from early to later buildings, and was struck by an obvious one in two back-to-back temples at a site not far from Thebes called Medinet-Habu (Fig. 22) and pointed out the similarity between this Egyptian and the Greek "difference of orientation" in temples that, from a purely architectural aspect, should have been parallel and with the same axial orientation.

Figure 22

Could the slightly altered orientation result from changes in the amplitude (the position in the skies) of the Sun or stars caused by the changes in the Earth's obliquity? he wondered, and felt that the answer was Yes. We now know that the solstices result from the fact that the Earth's axis is tilted relative to its plane of orbit around the Sun, and the points of "standstill" match the Earth's tilt. But astronomers established that this angle is not constant.

The Earth wobbles, like a pitching ship, from side to side - perhaps the lingering result of some mighty bang it received in its past (whether the original collision that put the Earth in its present orbit, or the crash of a massive meteor some 65 million years ago that may have extinguished the dinosaurs).

The present tilt of about 23.5 degrees can decrease to perhaps just 21° and on the other hand increase to well over 24° - no one can really say for sure, since the change by even 1° lasts thousands of years (7,000, according to Lockyer).

Such changes in the obliquity result in changes in the Sun's standstill points (Fig. 23a). This means that a temple built to a precise solstitial orientation at a given time is no longer properly aligned to that orientation several hundred, and certainly several thousand, years later. Lockyer's masterful innovation was this: by determining the orientation of a temple and its geographic longitude, it was possible to calculate the obliquity that prevailed at the time of construction; and by determining the changes in obliquity over the millennia, it was possible to conclude with sufficient certainty when the temple was constructed.

The Table of Obliquity, fine-tuned and made more ac-curate during the past century, shows the change in the angle of the Earth's tilt in five-hundred-year intervals, going back from the present 23° 27' (about 23.5 degrees): Lockyer applied his lindings primarily to extensive measurements at the great temple to Amon-Ra in Karnak.

This temple, having been enlarged and augmented by various pharaohs, consists of two principal rectangular structures built back-to-back on a southeast-northwest axis, signifying a solstitial orientation. Lockyer concluded that the purpose of the orientation and the layout of the temple was to enable a beam of sunlight to come from such a direction on solstice day that it would travel the length of a long corridor, pass between two obelisks, and strike the Holy of Holies with a flash of Divine Light at the temple's innermost sanctum.

Lockyer noticed that the axis of the two back-to-back temples was not similarly oriented: the newer axis represented a solstice resulting from a somewhat smaller obliquity than the older axis (Fig. 23b). The two obliquities determined by Lockyer show that the older temple was built circa 2100 BC. and the newer one circa 1200 BC. Figures 23a and 23b

Although more recent investigations, especially by Gerald S. Hawkins, suggest that the Sun's beam, at winter solstice, was meant to be viewed from a part of the temples Hawkins named "High Room of the Sun" and not as a beam traveling the length of the axis, the revision in no way changes the basic conclusion by Locker regarding the solstitial orientation.

Indeed, further archaeological discoveries at Kamak corroborate Lockyer's principal innovation - that the orientation of the temples changed in time to reflect the changes in obliquity. Therefore, the orientation could serve as a clue to the temples' time of construction, The latest archaeological advances confirmed that the construction of the oldest part coincided with the beginning of the Middle Kingdom under the XI dynasty circa 2100 BC.

Repairs, demolitions, and rebuilding then continued through the ensuing centuries by pharaohs of subsequent dynasties; the two obelisks were set up by pharaohs of the XVIII dynasty. The final phase took shape under the Pharaoh Seti II of the XIX dynasty who reigned in 1216-1210 BC. - all as Lockyer had determined. Archaeoastronomy - or, astroarchaeology as Sir Norman Lockyer named it - proved its merit and validity. At the beginning of this century Lockyer turned his attention to Stonehenge, having become convinced that the phenomenon he had discovered governed temple orientations in other parts of the ancient world, as at the Parthenon in Athens.

At Stonehenge the axis of viewing from the center through the Sarsen Circle clearly bespoke an orientation to the summer solstice, and Lockyer performed his measurements accordingly. The Heel Stone, he concluded, was the indicator of the point on the horizon where the expected sunrise was to happen; and the apparent shifting of the stone (with attendant widening and realignment of the Avenue) suggested to him that as the centuries passed and the change in the Earth's tilt kept changing the sunrise point, even if ever so slightly, the people in charge of Stonehenge kept adjusting the view line.

Lockyer presented his conclusions in Stonehenge and Other British Stone Monuments (1906); they can be summed up in one drawing (Fig. 24). It assumes an axis that begins at the Altar Stone, passes between the sarsen stones numbered 1 and 30, down the Avenue, toward the Heel Stone as the focusing pillar. The obliquity angle indicated by such an axis led him to suggest that Stonehenge was built in 1680 BC.

Figure 24 Needless to say, such an early date was quite sensational at a time, a century ago, when scholars still thought of Stonehenge in terms of King Arthur's days. The refinements in studies of the Earth's obliquity, allowances now made for margins of error, and the determination of the various phases of Stonehenge have not diminished Lockyer's basic contribution.

Although Stonehenge III, which is what we essentially see nowadays, is now dated to circa 2000 BC., it is generally agreed that the Altar Stone was removed when the remodeling began circa 2100 BC. with the double Bluestone Circle (Stonehenge II), and that it was re-erected where it is now only when the bluestones were reintroduced and the Y and Z holes dug. That phase, designated Stonehenge IIIb, has not been definitely dated; it is in a range between 2000 BC. (Stonehenge IIIa) and 1550 BC. (Stonehenge IIIc) - and quite possibly the 1680 BC. date arrived at by Lockyer. As the drawing shows, he did not rule out a much earlier date for the prior phases of Stonehenge; this too compares well with the presently accepted date of 2900/2800 BC. for Stonehenge I.

Archaeoastronomy thus joins archaeological findings and radiocarbon dating to arrive at the same dates for the construction of the various phases of Stonehenge, the three separate methods corroborating each other. With such a convincing determination of Stonehenge's dates, the question regarding its builders becomes more poignant. Who, circa 2900/2800 BC., possessed the knowledge of astronomy (to say nothing of engineering and architecture) to build such a calendrical "computer," and circa 2100/2000 BC. to rearrange the various components thereof and attain a new realignment? And why was such a realignment required or desired?

Mankind's transition from the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) that lasted for hundreds of thousands of years to the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) occurred abruptly in the ancient Near East. There, circa 11,000 BC. - right after the Deluge, according to our calculations - deliberate agriculture and the domestication of animals began in a stunning profusion. Archaeological and other evidence (most recently augmented by studies of linguistic patterns) shows that Mesolithic agriculture spread from the Near East to Europe as a result of the migration of people possessing such knowledge.

It reached the Iberian peninsula between 4500 and 4000 BC, the western edge of what is today France and the Lowlands between 3500 and 3000 BC., and the British Isles between 3000 and 2500 BC. It was soon thereafter that the "Beaker People," who knew how to make clay utensils, arrived on the Stonehenge scene. But by then the ancient Near East was already well past the Neolithic (New Stone Age) which began there circa 7400 BC.

Were the Sun Temples of Egypt, then, the prototypes for Stonehenge? We have seen that at the dates established for Stonehenge's various phases, there already existed in Egypt elaborate temples that were astronomically oriented. The equinoctial Sun Temple at Heliopolis was built at about the time, 3100 BC., when kingship began in Egypt (if not somewhat earlier) - several centuries before Stonehenge I. The construction of the oldest phase of the solstitially oriented temple to Amon-Ra in Karnak took place circa 2100 BC. - a date coinciding (perhaps not by chance) with the date for the "remodeling" of Stonehenge.

It is thus theoretically possible that Mediterranean people - Egyptians or people with "Egyptian" knowledge - could somehow account for the construction of Stonehenge I, II, and III at dates that were impossible for the local inhabitants of the area. While, from a timing point of view, Egypt could have been the source of the required knowledge, we ought to be bothered by a crucial difference between all of the Egyptian temples and Stonehenge: none of the Egyptian temples, no matter whether their orientation was equinoctial or solstitial, were circular as Stonehenge has been during all of its phases.

The various pyramids were square-based; the podiums for the obelisks and pyramidions were square; the numerous temples were all rectangular. With all the stones of Egypt, not one of its temples was a stonehenge. From the beginning of dynastic times in Egypt, with which the appearance of a distinct Egyptian civilization is linked, it was the pharaohs of Egypt who had hired the architects and masons, the priests and savants, and decreed the planning and construction of the marvelous stone edifices of ancient Egypt.

None of them, however, appears to have designed, oriented, and built a circular temple. What about those famous seafarers, the Phoenicians? Not only did they reach the British Isles (mainly in search of tin) too late to have built not just Stonehenge I but also the II and III phases, but none of their temple architecture bears any resemblance to the emphatically circular essence of Stonehenge. We can see a Phoenician temple depicted on the Byblos coin (Fig. 12). and it is certainly rectangular.

On the vast stone platform at Baalbek in the Lebanon mountains, people after people and conquerors after conquerors built their temples precisely on the ruins and according to the layout of preceding temples. These, as the latest extant ruins from the Roman era reveal (Fig. 25), represented a rectangular temple (black area) with a square forecourt (the diamond-shaped entrance pavilion is a purely Roman addition). Figure 25

The temple is clearly oriented on an east-west axis, facing directly east toward the Sun at sunrise- - an equinoctial temple. This should perhaps be no surprise, since in ancient times this site too was called "City of the Sun" - Heliopolis by the Greeks, Beth-Shemesh ("House of the Sun") in the Bible, in King Solomon's time.

That the rectangular shape and east-west axis were not a passing fad in Phoenicia is further evidenced by the Temple of Solomon, the first temple of Jerusalem, which was built with the aid of Phoenician architects provided by Ahiram, king of Tyre; it was a rectangular structure on an east-west axis, facing eastward (Fig. 26), built upon a large man-made platform. Figure 26

Sabatino Moscati (The World of the Phoenicians) stated without qualification that,

And nothing about them was circular. Circles do appear, though, in the case of the other Mediterranean "suspects" - the Mycenaeans, the first Hellenic people of ancient Greece. But these were at first what archaeologists call Grave Circles - burial pits surrounded by a circle of stones (Fig. 27) that evolved into circular tombs hidden beneath a conical mound of soil.

Figure 27

But that had taken place circa 1500 BC. and the largest of them, called the Treasury of Atreus because of the golden artifacts that were found around the dead (Fig. 28), dates to circa 1300 BC.

Figure 28

Archaeologists who adhere to the Mycenaean connection compare such eastern Mediterranean burial mounds to Silbury Hill in the Stonehenge area or to one at Newgrange, across the Irish Sea in Boyne Valley, County Meath, in Ireland; but Silbury Hill has been determined by carbon dating to have been constructed not later than 2200 BC. and the burial mound at Newgrange at about the same time - almost a thousand years before the Treasury of Atreus and other Mycenaean examples; the period of the Mycenean burial mounds, moreover, is even farther removed from the time of Stonehenge 1.

In fact, the burial mounds in the British Isles arc much more akin, in construction and in timing, to such mounds in the western rather than eastern Mediterranean, such as the one in Los Millares in southern Spain (Fig. 29). Above all, Stonehenge has never served as a burial place. For all these reasons, the search for a prototype - a circular structure serving astronomical purposes - should continue beyond the eastern Mediterranean. Figure 29

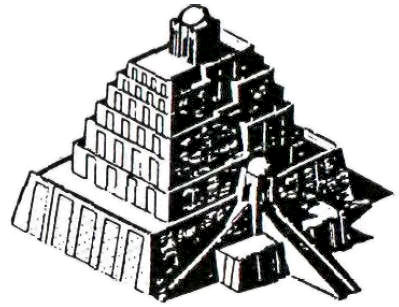

Older than the Egyptian civilization and possessing much more advanced scientific knowledge, the Sumerian civilization could have served, theoretically, as the fountainhead for Stonehenge. Among the astounding Sumerian achievements were great cities, a written language, literature, schools, kings, courts, laws, judges, merchants, craftsmen, poets, dancers. The sciences flourished within the temples, where the "secrets of numbers and of the heavens" - of mathematics and astronomy - were kept, taught, and transmitted by generations of priests who performed their functions within walled-off sacred compounds.

Such compounds usually included shrines dedicated to various deities, residences, work and study places for the priests, storehouses and other administrative buildings, and - as the dominant, principal, and most prominent feature of the sacred precinct and of the city itself - a ziggurat, a pyramid that rose sky high in stages (usually seven). The topmost stage was a multichambered structure that was intended - literally - to be the residence of the great god whose "cult center" (as scholars like to call it) the city was (Fig. 30).

Figure 30

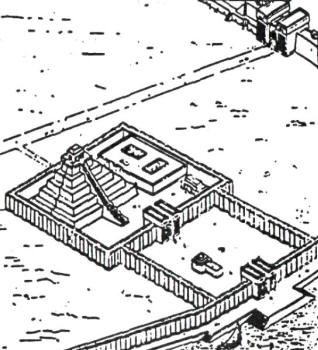

A good illustration of the layout of such a sacred precinct with its ziggurat is a reconstruction based on archaeological discoveries at the sacred precinct of Nippur (NI.IBRU in Sumerian), the "headquarters" from the earliest days of the god Enlil (Fig. 31); it shows a ziggurat with a square base within a rectangular compound.

As luck would have it, archaeologists have also unearthed a clay tablet upon which an ancient cartographer drew a map of Nippur (Fig. 32); it clearly shows the rectangular sacred precinct with the square-based ziggurat, the caption (in cuneiform script) for which states its name, the E.KUR - "House, which is like a mountain." Figure 31

Figure 32 (click to enlarge)

The orientation of the ziggurat and temples was such that the corners of the structures pointed to the four cardinal points of the compass, so that the sides of the structure faced to the northeast, southwest, northwest, and southeast. To orient the ziggurats' corners to the cardinal points - without a compass - was not an easy achievement. But it was an orientation that made it possible to scan the heavens in many directions and angles.

Each stage of the ziggurat provided a higher viewing point and thus a different horizon, adjustable to the geographic location; the line between the east-pointing and west-pointing corners provided the equinoctial orientation; the sides gave solstitial views to either sunrise or sunset, at both summer and winter solstices.

Modern astronomers have found many of these observational orientations in the famed ziggurat of Babylon (Fig. 30), the site was known in early Irish lore by various names that all designated it as Brug Oengusa, the "House of Oengus," son of the chief god of the pre-Celtic pantheon who had come to Ireland from "the Otherworld."

That chief god was known as An Dagda, "An, the good god"... It is indeed amazing to find the name of the principal deity of the ancient world in all these diverse places - in Sumer and his E.ANNA ziggurat of Uruk; in the Egyptian Heliopolis, whose true name was Annu; and in far-removed Ireland...

That this might be an important clue and not just an insignificant coincidence becomes possible when we ex-amine the name of the son of this "chief god," Oengus.

When the Babylonian priest Berossus wrote, circa 290 BC., the history and prehistory of Mesopotamia and Mankind according to the Sumerian and Babylonian records, he (or the Greek savants who copied from his works) spelled the name of Enki "Oannes." Enki was the leader of the first group of Anunnaki to splash down to Earth, in the Persian Gulf; he was the chief scientist of the Anunnaki and the one who inscribed all knowledge on the ME's, enigmatic objects that, with our present knowledge, one could compare to computer memory discs.

He was indeed a son of Anu; was he then the god who in pre-Celtic myth became "Oengus, the son of An Daga?

"All that we know, we were taught by the gods," the Sumerians

repeatedly stated. Was it, then, not the ancient peoples, but the

ancient gods who created Stonehenge?

|