Chapter 1 - Messianic and Visionary Recitals

These texts constitute some of the most thought-provoking in the corpus. We have

placed them in the first Chapter because of the importance of their Messianic,

visionary and mystical - even Kabbalistic - content and imagery. These are not

the only texts with such import. This kind of thrust will grow to a climax in

Chapters 5 and 7.

But the Messianic theorizing these texts exhibit is particularly interesting -

it has heretofore either been underestimated or for some reason played down in

the study of the Scrolls. In at least two texts in this Chapter (not to mention

other Chapters), we have definite Messianic allusions: the Messianic vision text

we call, after an allusion in its first line, the Messiah of Heaven and Earth,

and the Messianic Leader (Nasi) text. In both there are clear correspondences to

recognized Messianic sections in the Prophet Isaiah.

Interestingly, we do not have the two-Messiah doctrine highlighted in a few of

the texts from the early days of Qumran research, like the Damascus Document

found in two recensions at the end of the last century in the Cairo Genizah or

the Community Rule from Cave 1, but rather the more normative, single Messiah

most Jews and Christians would find familiar. Though in the Messianic Leader (Nasi)

text, this figure is nowhere declared to be a ‘Messiah’ as such, only a

Messianic or eschatological ‘Leader’, the Messianic thrust of the Biblical

allusions underpinning it and the events it recounts clearly carry something of

this signification.

Its relation to the Damascus Document, further discussed in

our analysis of the Messianic Florilegium in Chapter 4, do as well. But even in

the published corpus, there is a wide swath of materials, particularly in the

Biblical commentaries (the pesharim) on Isaiah, Zechariah, Psalms, etc., and

compendiums of Messianic proof texts, that relate to a single, more nationalist,

Davidic-style Messiah, as opposed to a second with more priestly characteristics

that has been hypothesized. This last is, of course, in evidence too in the

Letter to the Hebrews, where the more eschatological and high-priestly

implications of Messiah-ship are expounded.

Even in the Damascus Document, there is some indication in the first column of

the Cairo recension that the Messianic ‘Root of Planting out of Aaron and

Israel’ has already come. The ‘arising’ or ‘standing up’ predicted in the later

sections can be looked upon, as well, as something in the nature of a Messianic

‘return’ - even ‘resurrection’ (see Dan. 12:13 and Lam R ii-3.6 using ‘amod or

‘standing up’ in precisely this vein and our discussion of the Admonitions to

the Sons of Dawn below).

Nor is it completely clear in the Cairo Damascus

Document that the allusion to ‘Aaron and Israel’ implies dual Messiahs, and not

a single Messiah out of two genealogical stalks, which was suggested by scholars

in the early days of research on it, and is, as we shall see, the more likely

reading.

The very strong Messianic thrust of many of the materials associated with Qumran

has been largely

overlooked by commentators, in particular the presence in the published corpus

in three different

places of the ‘World Ruler’ or ‘Star’ prophecy from Num. 2 4:17 - that ‘a Star

would rise out of Jacob, a

Sceptre to rule’ the world - i.e. in the Damascus Document, the War Scroll, and

one of the

compendiums of Messianic proof texts known as a Florilegium. There can be little

doubt that the rise

of Christianity is predicated on this prophecy. Our own Genesis Florilegium,

playing on this title, also

ends up with an exposition of another famous Messianic prophecy - the ‘Shiloh’

from Gen. 49:10, which also includes the ‘sceptre’ aspect of the above prophecy.

The first-century Jewish historian Josephus, an eye-witness to the events he

describes, identifies the world ruler prophecy as the moving force behind the

Jewish revolt against Rome in AD 66-70 (War 6.317). Roman writers dependent on

him, like Suetonius (Twelve Caesars 10.4) and Tacitus (The Histories 2.7 8 and

5.13) do likewise. Rabbinic sources verify its currency in the events

surrounding the fall of the Temple in AD 7 0 (ARN 4 and b. Git 56b).

However,

reversing its thrust, these last present their hero, the Rabbi Yohanan b.

Zacchai as applying it - as Josephus himself does - to the destroyer of

Jerusalem and future Roman Emperor Vespasian! The Bar Kochba uprising in AD

132-6 can also bethought of as being inspired by this prophecy, as Bar Kosiba’s

original name seems to have been deliberately transmuted into one incorporating

this allusion, i.e. Bar Kochba - ‘Son of the Star’.

The other texts in this

section are all visionary and eschatological, most often relating to Ezekiel,

the original visionary and eschatological prophet and a favourite in Qumran

texts. Whatever else can be said of them, their nationalist, militant,

apocalyptic and unbending thrust cannot be gainsaid, nor should it be

overlooked.

Back to Contents

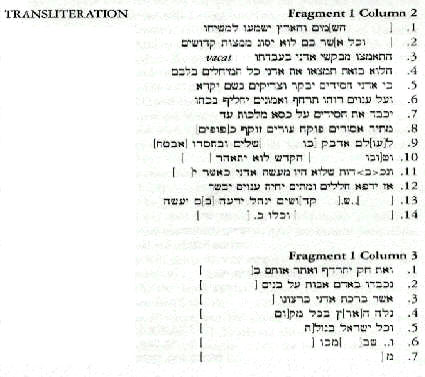

1. The Messiah Of Heaven And Earth (4Q521) (Plate 1)

This text is one of the most beautiful and significant in the Qumran corpus. In

it many interesting themes that appear in other Qumran texts reappear. In the

first place, there is continued emphasis on ‘the Righteous’ (Zaddikim), ‘the

Pious’ (Hassidim), ‘the Meek’ (‘Anavim), and ‘the Faithful’ (Emunim). These

terms recur throughout this corpus (in particular see the Hymns of the Poor

below) and should be noted as more or less interchangeable allusions and

literary self-designations.

The first two are important in the vocabulary of

Jewish mysticism; the last two in that of Christianity. New themes also appear,

such as God’s ‘Spirit hovering over the Meek’ and ‘announcing glad tidings to

the Meek’, themes with clear New Testament parallels. These also include the

Pious being ‘glorified on the Throne of the Eternal Kingdom’, which resonates as

well with similar themes in the New Testament and the Kabbalah, and God

‘visiting the Pious’ and ‘calling the Righteous by name’, both paralleled in the

Damascus Document. In CD, i.7 God is said to have ‘visited’ the earth causing,

as we have seen, a Messianic ‘Root of Planting’ to grow, and following this, in

iv.4, ‘the sons of Zadok’ are described as being ‘called by name’.

This phrase

‘called by name’ is also found in column ii. II of the Damascus Document, where

it is followed by the statement that God ‘made His Holy Spirit known to them by

the hand of His Messiah’- words which resonate with the language of the present

text as well.

Not only do parallel allusions confirm the relationship of the

‘sons of Zadok’ with the ‘Zaddikim’ (‘the Righteous’/’Righteous Ones’), but

‘naming’ and predestination are important themes in both the early columns of CD

and Chapters 2 - 5 of Acts, where, for instance, the predestination of Christ

and the language of the Holy Spirit are signaled. If the additional fragments of

this text - which may or may not be integral to it - are taken into

consideration, then there is some allusion to ‘anointed ones’ or ‘messiahs’

plural, probably referring to the priests doing service in the Temple.

The two

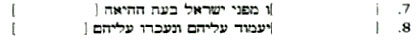

columns of the major fragment on this plate (no. 1) very definitely, however,

evoke a singular, nationalist Messiah, as does the interpretation of the ‘Shiloh

Prophecy’ related to it in the Genesis Florilegium below.

He is to a certain extent a supernatural figure in the manner of Dan. 7’s ‘Son

of Man coming on the clouds of Heaven’. This imagery is recapitulated in Column

xif. of the War Scroll from Cave 1 at Qumran, which interprets the ‘Star

Prophecy’ in terms of it and the rising of ‘the Meek’ in some final apocalyptic

war. The War Scroll, of course, also uses eschatological ‘rain’ imagery to

identify these ‘clouds’ with the ‘Holy Ones’ (‘the Kedoshim’ or ‘Heavenly

Host’).

In the Messiah of Heaven and Earth text, not only are the ‘heavens and

the earth’ subsumed under the command of the Messiah, but so, too, are these

presumed ‘Kedoshim’ or ‘Holy Ones’ from the War Scroll. There are also the very

interesting allusions to ‘My Lord’ / Adonai, referred to in Isa. 6 1:1, which

seems to underlie much of the present text; but since the sense of this is often

so imprecise, it is impossible to tell whether the reference is to God or to

‘His Messiah’ whom it so celebrates.

If the latter, this would bring its imagery

closer still to similar New Testament recitations. The reader should note,

however, that for Josephus mentioned above, one of the determining

characteristics of those he calls Essenes and Zealots was that they would not

‘call any man Lord’ (italics ours). By far the most important lines in Fragment

1 Column 1 are Lines 6-8 and 11- 13, referring to ‘releasing the captives’,

‘making the blind see’, ‘raising up the downtrodden’, and ‘resurrecting the

dead’. The last allusion is not to be doubted. The only question will be, who is

doing this raising, etc. - God or ‘His Messiah’? In Lines 6-8 the reference

seems to be to God. But in Lines 11- 13, it is possible that a shift occurs, and

the reference could be to ‘His Messiah’. The editors were unable to agree on the

reconstruction here.

In any event, language from Isa. 6 1:1 (see above) is also clearly identifiable

in both line 8 and line 11. But likewise, there are word for-word

correspondences to the Eighteen Benedictions, among the earliest strata of

Jewish liturgy and still a part of it today: ‘You will resurrect the dead,

uphold the fallen, heal the sick, release the captives, keeping faith with those

asleep in the dust...’, referring obviously to God.

It should be noted too that

these portions include reference to the Hassidim, also evoked several times in

the present text. It is also interesting to note that Isa. 60:2 1, which

precedes Isa. 61:1, contains the ‘Root of Planting’ imagery used in the first

column of the Damascus Document referred to above and the ‘Branch’ imagery that

will be so prominent in the Messianic Leader (Nasi) text that follows below.

The reference to ‘raising the dead’ solves another knotty problem that much

exercised Qumran commentators, namely whether those responsible for these

documents held a belief in the resurrection of the dead. Though there are

numerous references to ‘Glory’ and splendid imagery relating to Radiance and

Light pervading the Heavenly abode in many texts, this is the first definitive

reference to resurrection in the corpus. It should not come as a surprise, as

the belief seems to have been a fixture of the Maccabean Uprising as reflected

in 2 Macc. 12:44-45 and Dan. 12:2, growing in strength as it came down to

first-century groups claiming descent from these archetypical events.

Translation

Fragment 1

Column 2 (1)[... The Hea]vens and the earth will obey His Messiah,

(2) [... and all th]at is in them. He will not turn aside from the Commandments

of the Holy Ones. (3) Take strength in His service, (you) who seek the Lord. (4)

Shall you not find the Lord in this, all you who wait patiently in your hearts?

(5) For the Lord will visit the Pious Ones (Hassidim) and the Righteous (Zaddikim)

will He call by name. (6) Over the Meek will His Spirit hover, and the Faithful

will He restore by His power. (7) He shall glorify the Pious Ones (Hassidim) on

the Throne of the Eternal Kingdom. (8) He shall release the captives, make the

blind see, raise up the do[wntrodden.] (9) For[ev]er will I cling [to Him ...],

and [I will trust] in His Piety (Hesed, also ‘Grace’), (10) and [His] Goo[dness...] of Holiness will not delay ...(11) And as for the wonders that are not

the work of the Lord, when He ... (12) then He will heal the sick, resurrect the

dead, and to the Meek announce glad tidings. (13)... He will lead the [Holly

Ones; He will shepherd [th]em; He will do (14)...and all of it... Fragment l

Column 3 (1) and the Law will be pursued. I will free them ... (2) Among men the

fathers are honored above the sons ...(3)I will sing (?)the blessing of the Lord

with his favor...(4) The 1[an]d went into exile (possibly, ‘rejoiced) every-wh[ere...] (5) And all Israel in exil[e (possibly ‘rejoicing’) ...] (6) ... (7) ...

Fragment 2

(1) ... their inheritan[ce...] (2) from him ...

Fragment 3 Column 1 (4) ... he will not serve these people (5) ... strength ()

... they will be great Fragment 3 Column 2 (1) And... (3) And ... (5) And ...

(6) And which ... (7) They gathered the noble[s...] (8) And the eastern parts of

the heavens ... (9) [And] to all yo[ur] fathers ... Fragment 4 (5) ... they will

shine (6)... a man (7) ... Jacob (8)... and all of His Holy implements (9)...

and all her anointed ones (10)... the Lord will speak... (11) the Lord in

[his] might (12)... the eyes of Fragment 5 (1)... they [will] see all... (2) and everything in it... (3) and all the fountains of water, and the

canals... (4) and those who make... for the sons of Ad[am...] (5) among

these curs[ed ones.] And what ...(6) the soothsayers of my people ... (7) for

you ... the Lord ... (8) and He opened...

Back to Contents

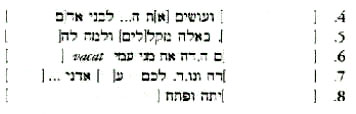

2. The Messianic Leader (NASI - 4Q285) (Plate 2)

We released this text at the height of the controversy over access to the Dead

Sea Scrolls in November

1991. Since then much discussion has occurred concerning it. Our purpose in

releasing it was to show that there were very interesting materials in the

unpublished corpus which for some reason had not been made public and to show

how close the scriptural contexts in which the movement or community responsible

for this text and early Christianity were operating really were. However one

reconstructs or translates this text, it is potentially very explosive.

As it

has been reconstructed here, it is part of a series of fragments. There is no

necessary order to these fragments, nor in that of other similar materials

reconstructed in this book. Such materials are grouped together on the basis

either of content or handwriting or both, and the criterion most often employed

is what seemed the most reasonable.

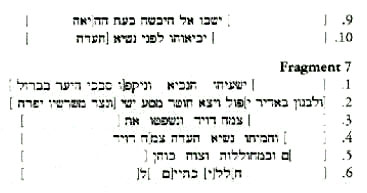

Here, the key question is whether Fragment 7 comes before or after Fragment 6.

If after, as we have placed it in our reconstruction, then the Messianic Nasi or

‘Leader’ would be alive after the events described in Fragment 6 and could he

the one ‘put to death’. This was our initial assessment. If before, then it is

possible that the Messianic Leader does the ‘putting to death’ mentioned in the

text, though such a conclusion flies in the face of the logic of the appositives

like ‘the Branch of David...’ grouped after the expression ‘the Nasi ha—‘Edah’,

which would be clumsy even in Hebrew.

Another question that will arise

concerning this text is whether the individual who appears to be brought before

‘the Leader of the Community’ in Fragment 6 is the same as the one referred to

in Fragment 7 by the pronoun ‘him’, if in fact a him’ can be read into this line

at all and not simply the plural of the verb, ‘kill/killed’. In Hebrew the

spelling is the same. The reader should keep in mind that whether there is any

real sequentiality in these fragments or whether they even go together at all is

conjectural, and these questions will probably not be resolved on the basis of

the data before us.

In favour of the Nasi ha—‘Edah being killed - which, all

things being equal, makes most sense if Fragment 7 is considered by itself only

- even without the accusative indicator in Biblical Hebrew, ‘et’ there are many

texts at Qumran and from the Second Temple period generally that are not careful

about the inclusion of the object indicator in their Hebrew, including the

Messiah of Heaven and Earth above and the Eighteen Benedictions mentioned above.

Another counter example where the object indicator is not employed occurs m

Column ü.12 of the Damascus Document, where reference is made to ‘His Messiah

making known the Holy Spirit’, also mentioned above. Concerning whether our

reconstruction of Line 4 of Fragment 7 attaching ‘the Branch of David’ to ‘the

Leader of the Community’ is correct, it is interesting to note that not only is

‘the Prophet Isaiah’ mentioned in Line 1, but Line 2 quotes 11:1: ‘A staff shall

rise from the stem of Jesse and a shoot shall grow from his roots.’ There even

seems to be an allusion to its second line, ‘the Spirit of the Lord shall rest

upon Him’, in Line 6 of the Messiah of Heaven and Earth above, and we will see

this same passage actually evoked at the end of the beautiful Chariots of Glory

text in Chapter 7 below.

This prophecy was obviously a favourite proof text at

Qumran, as it very definitely was in early Christianity. But this prophecy has

already been subjected to exegesis in the already-published Isaiah Commentary

{a} from Cave 4. There are many such overlaps in Qumran exegeses, including that

of the ‘Star Prophecy’ already noted.

In 4QpIs{a}, the exegesis of Isa. 11:1- 3 is preceded by one of Isa. 10:33-4

about ‘Lebanon being

felled by a Mighty One’ amid allusions to ‘the warriors of the Kittim’ and

‘Gentiles’. This seems to be the case in the Messianic Leader (Nasi) text as

well, where allusions to ‘the Kittim’ in other fragments - including ‘the slain

of the Kittim’ abound, showing the context of the two exegeses to have been more

or less parallel.

These kinds of texts about ‘the falling of the cedars of

Lebanon’ or ‘Lebanon being felled by a Mighty One’, as it is expressed in both

texts, usually bear on the fall of the Temple or the priesthood. In Rabbinic

literature, Isa. 10:3 3 -4 is interpreted in this way, and specifically and one

might add definitively - tied to the fall of the Temple in AD 70 (see ARN 4 and

b. Girt 56ª). Sometimes ‘Lebanon’ imagery, which like ‘Kittim’ is used across

the board in Qumran literature, relates especially when the imagery is positive,

to the Community leadership.

The reference is to the ‘whitening’ imagery

implicit in the Hebrew root ‘Lebanon’. This is played upon to produce the

exegesis, either to Temple, because the priests wore white linen there or to the

Community Council, presumably because its members also appear to have worn white

linen. Readers familiar with the New Testament will recognize ‘Community’ and

‘Temple’ here as basically parallel allusions, because just as Jesus is

represented as ‘the Temple’ in the Gospels and in Paul, the Community Rule,

using parallel spiritualized ‘Temple’ imagery in viii. 5 -6 and ix.6, pictures

the Qumran Community Council as a ‘Holy of Holies for Aaron and a Temple for

Israel’. This imagery, as we shall see, is widespread at Qumran, including

parallel allusions to ‘atonement’, ‘pleasing fragrance’, ‘Cornerstone’, and

‘Foundation’ which go with it.

Completing the basic commonality in these texts, 4QpIs{a} also sympathetically

evokes ‘the Meek’ and goes on to relate Isaiah 11:1’s ‘Staff’ or ‘Branch’ to the

‘Branch of David’ in Jeremiah and Zechariah. Highlighting these Messianic and

eschatological implications, it describes the Davidic ‘Branch’ as ‘standing at

the end of days’ (note the language of ‘standing’ again). In the process, it

incorporates ‘the Sceptre’ language from the ‘Star Prophecy’, which will also

reappear, as we shall see, in the Shiloh Prophecy in the Genesis Florilegium

below. The ‘Star Prophecy’, too, as the reader will recall, was quoted in a

passage in the War Scroll with particular reference to ‘the Meek’. The War

Scroll too makes continual reference to ‘Gentiles’ and ‘Kittim’.

To complete the circularity, 4Qpls{a} ends with an evocation of ‘the Throne of

Glory’, again mentioned in the Messiah of Heaven and Earth text above and

alluded to in jet. 33:18 - which in turn also evokes ‘the Branch of David’ again

and other texts below like the Hymns of the Poor and the Mystery of Existence.

We are clearly in a wide-ranging universe here of interchangeable metaphors and

allusions from Biblical scripture.

The reference to ‘woundings’ or pollution’s in Line 5 of Fragment 7 of the

present text and the total ambiance of reference to Messianic prophecy from

Isaiah, Jeremiah, Zechariah, etc. heightens the impression that a Messianic

‘execution’ of some kind is being referred to. This is also the case in Isa.

11:4 where the Messianic Branch uses ‘the Sceptre of his mouth ... to put to

death the wicked’, however this is to be interpreted in this context.

The reader should appreciate that the Nasi ha-‘Edah does not necessarily

represent a Messiah per se,

though he is being discussed in this text in terms of Messianic proof texts and

allusions. ‘Nasi’ is a

term used also in Column v. l of the Damascus Document when alluding to the

successors of David. In

fact, the term ‘Nasi ha—‘Edah’ itself actually appears in CD’s critical

interpretation of the ‘Star

Prophecy’ in Column vii, which follows. In its exegesis CD ties it to ‘the

Sceptre’ as we shall see in

Chapter 3 below.

Not only is it used in Talmudic literature to represent scions

of the family of David, but coins from the Bar Kochba period also use it to

designate their hero, i.e. ‘Nasi Israel’ ‘Leader of Israel’. Today the term is

used to designate the President of the Jewish State. This reference to meholalot

(woundings) in Line 5 of Fragment 7, followed by an allusion to ha-cohen (the

priest) - sometimes meaning the high priest - would appear to refer to an

allusion from Isa. 5 3:5 related to the famous description there of the

‘Suffering Servant’, so important for early Christian exegetes, i.e. ‘for our

sins was he wounded’ or ‘pierced’.

Though it is possible to read meholalot in

different ways, the idea that we have in this passage an allusion to the

‘suffering death’ of a Messianic figure does not necessarily follow, especially

when one takes Isa. 11:4 into consideration. Everyone would have been familiar

with the ‘Suffering Servant’ passages in Isaiah, but not everyone would have

used them to imply a doctrine of the suffering death of a Messiah.

In fact, it

is our view that the progenitors of the Qumran approach were more militant,

aggressive, nationalistic and warlike than to have entertained a concept such as

this in anything more than a passing manner. It has also been argued that this

Messianic Nasi text should be attached to the War Scroll. This would further

bear out the point about violent militancy, because there is no more warlike,

xenophobic, apocalyptic and vengeful document - despite attempts to treat it

allegorically - in the entire Qumran corpus than the War Scroll.

There can be no mistaking this thrust in the present document, nor the parallel

4QpIs{a}. Its nationalistic thrust should be clear, as should its Messianism. If

these fragments do relate to the War Scroll, then they simply reinforce the

Messianic passages of the last named document. The ‘Kittim’ in the War Scroll

have been interpreted by most people to refer to the Romans. The references to

Michael and the ‘Kittim’ in the additional fragments grouped with the present

text simply reinforce these connections, increasing the sense of the Messianic

nationalism of the Herodian period. However these things may be, the

significance of all these allusions coming together in a little fragment such as

this cannot be underestimated.

Translation

Fragment 1

(1) ... the Levites, and ha[lf...] (2) [the ra]m’s horn, to blow on

them ... (2) the Kittim, and

...

Fragment 2

(1)... and against ...(2) for the sake of Your Name ... (3) Michael

...(4) with the Elec[t...] Fragment 3 (2)...rain ...and spring [rain ...] (3) as

great as a mountain. And the earth ... (4) to those without sense ... (5) he

will not gaze with Understand[ing ...] (6)from the earth. And noth[ing ...] (7)

His Holiness. It will be called ... (8) your...and in your midst...

Fragment 4

(1) ... until ... (2) you to (or ‘God’)...(3)and in Heaven ...(4) in

its time, and to...(5)[he]art, to...(6)and not... (7) all... (8) for God...

Fragment 5

(1) ...from the midst of[the]community ...(2) Riches [and] booty .. .

(3) and your food . ..

(4) for them, grave[s . ..] (5) the[ir] slain... (6) of iniquity will return... (7) in compassion and...

(8) Is[r]ael...

Fragment 6

(1)... Wickedness will be smitten ...(2) [the Lea]der of the

Community and all Isra[el...] (4) upon the mountains of... (5) [the]

Kittim... (<) [the Lea]der of the Community as far as the [Great] Sea...

(7) before Israel in that time . .. (8) he will stand against them, and they

will muster against them ...(9) they will return to the dry land in th[at] time

...(10) they will bring him before the Leader of [the Community ...]

Fragment 7

(1) ... Isaiah the Prophet, [’The thickets of the forest] will be fell[ed with

an axe] (2) [and Lebanon shall f]all [by a mighty one.] A staff shall rise from

the root of Jesse, [and a Planting from his roots will bear fruit.’] (3)...

the Branch of David. They will enter into judgement with ...(4) and they will

put to death the Leader of the Community, the Bran[ch of David] (this might also

be read, depending on the context, ‘and the Leader of the Community, the Bran[ch

of David’], will put him to death) ... (5) and with woundings, and the (high)

priest will command ... (G)

[the sl]ai[n of the] Kitti[m]...

Back to Contents

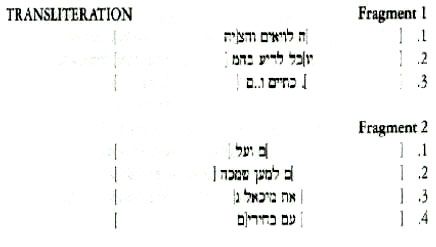

3. The Servants Of Darkness (4Q471)

This is a text of extreme significance and another one related to the War

Scroll. The violence, xenophobia, passionate nationalism and concern for

Righteousness and the Judgements of God are evident throughout. Though these may

have a metaphoric meaning as well as an actual one, it is impossible to think

that those writing these texts were not steeped in the ethos of a militant army

of God, and hardly that of a peaceful, retiring community. Their spirit is

unbending, uncompromising. They give no quarter and expect none.

There is the particularly noteworthy stress on ‘Lying’, a theme one finds across

the spectrum of Qumran literature, in particular where the opponents of the

community or movement responsible for these writings are concerned. There is

also the actual use of the verb ma’as (meaning to ‘reject’ or ‘deny’) in

Fragment 2.7, paralleling similar usages in the Community Rule, the Habakkuk

Pesher, etc.

In texts such as these, ma~as is always used to portray the

activities of the ideological adversary of the Righteous Teacher, the ‘Liar’/

‘Spouter’ who ‘rejects the Law in the midst of the whole congregation’ or the

parallel activities of those archetypical ‘sons/servants of Darkness’ who do

likewise. Here it is used in contradistinction to ‘choosing’ in this case the

groups’ opponents reverse the natural order; they ‘choose the Evil’, instead of

‘the Good’, which they ‘reject’.

Similar reversals occur across the board in Qumran literature - one particularly

noteworthy one in Column i of the Damascus Document, where ‘justifying the

Wicked and condemning the Righteous’ on the part of ‘the Breakers’ of both ‘Law

and Covenant’ is juxtaposed in Column iv with the proper order noted below of

‘justifying the Righteous and condemning the Wicked’. This last is definitive of

‘the sons of Zadok’, itself synonymous probably too with ‘the Zaddikim’ in Line

5 of the Messiah of Heaven and Earth text. Both texts use the same reference,

‘called by name’, as descriptive of these respective terminologies.

There is the usual emphasis on fire, presumably the judgements of Hellfire, and

there is no shirking the duty for war, which is to be seen in some sense, if

Fragment 4 is taken into account, as being fought under levitical or priestly

command (cf. War Scroll ii. l- 3). There is the usual emphasis on ‘works’

(Fragment 2, Column 4 reconstructed) and particularly noteworthy is the

reference to ‘Servants of Darkness’ as opposed presumably to ‘Servants of

Light’.

The Jamesian parallels to the theme of ‘works’ should be clear; so too should

Paul’s characterization in 2 Cor. 11-12 of the Hebrew ‘archapostles’ -

presumably including James - as disguising themselves as ‘Servants of

Righteousness’ (cf. the actual use of this allusion in the Testaments of

Naphtali below) and ‘apostles of Christ’, when in fact they are ‘dishonest

workmen and counterfeit apostles’.

Paul also employs ‘Light’ terminology in this

passage, not to mention an allusion to ‘Satan’ so important in referring to Mastemoth /Mastema and its parallels below, i.e. ‘even Satan disguises himself

as an Angel of Light.’ Emphasizing ‘Truth’ (the opposite, it will be noted, of

‘Lying’) and at the same time parodying the position of everyman according to

his works, in 11:31 he revealingly insists, ‘he does not lie’, thus

demonstrating his awareness of the currency of these kinds of accusations at

this time.

His application of such ‘Lying’ terminology so widespread in these Qumran

documents - to himself, even if inadvertently, is noteworthy indeed.

One should also note, in particular, the widespread vocabulary of ‘Judgement’,

the ‘Heavenly Hosts’ and even ‘pollution’. Notice, too, the consistent emphasis

on ‘Righteousness’ and ‘Righteous judgement’, and on ‘keeping’, i.e. ‘keeping

the Law’ - ‘Covenant’ in this text. The group responsible for these writings is

extremely Law oriented and their zeal in this regard is unbending. The very use

of the word ‘zeal’ connects the literature with the Zealot mentality and

movement.

The terms ‘keeping’ and ‘Keepers of the Covenant’ also relate to the

second definition in Column 4 of the Community Rule of ‘the sons of Zadok’, a

term with probable esoteric parallels and variations in ‘sons of Righteousness’,

as we have seen above. One should also note the use of the word ‘reckoned’ in

Line 5 of Fragment 1, which resonates with the use of this term in the key

Letters on Works Righteousness below in Chapter 6.

Translation

Fragment 1

(1) ... the time You have commanded them not to (2) ... and you shall

lie about His Covenant (3) ... they say, ‘Let us fight His wars, for we have

polluted (4)... your [enemie]s shall be brought low, and they shall not know

that by fire (5)... gather courage for war, and you shall be reckoned (6)... you

shall ask of the experts of Righteous judgement and the service of (7)... you

shall be lifted up, for He chose [you]... for shouting (8) ... and you shall

bur[n...]and sweet...

Fragment 2

(2) to keep the testimonies of our Covenant

...(3) all their hosts in forbear[ante...] (4) and to restrain their heart

from every w[ork ...(5) Se]wants of Darkness, because the judgement ...(6) in

the guilt of his lot... (7) [to reject the Go]od and to choose the Evil...

(8) God hates and He will erect ...

(9) all the Good that...

Fragment 3

(2) Eternal, and He will set us ...(3)[He jud]ges His people in

Righteousness and [His] na[tion in ...] (4) in all the Laws of ...(5) us in

[our]sins...

Fragment 4

(1) from all tha[t...] (2) every man from his brother, because (3)

... and they shall remain with Him always and shall se[rvel (4) ... each and

every tribe, a man (5) . . [twen]ty-[six] and from [the] Levites six(6) [teen...] and [they] shall se[rve before Him] always upon (7)... [in] order that

they may be instructed in ...

Back to Contents

4. The Birth Of Noah (4Q534-536)

A pseudepigraphic text with visionary and mystical import, the several fragments

of this text give us a wonderfully enriched picture of the figure of Noah, as

seen by those who created this literature. In the first place, the text

describes the birth of Noah as taking place at night, and specifies his weight.

It describes him as ‘sleeping until the division of the day’, probably implying

noon.

One of the primordial Righteous Ones whose life and acts are soteriological in nature, Noah is of particular interest to writers of this

period like Ben Sira and the Damascus Document. The first Zaddik (Righteous One)

mentioned in scripture (Gen. 6:9), Noah was also ‘born Perfect’, as the rabbis

too insist, as is stressed in this passage. Because of this ‘Perfection’,

Rabbinical literature has Noah born circumcized.

However this may be,

‘Perfection’ language of this kind is extremely important in the literature at

Qumran, as it is in the New Testament. See, in this regard, the Sermon on the

Mount’s parallel: ‘Be perfect as your Father in Heaven is Perfect’ (Matt. 5:48).

‘Perfection’ imagery fairly abounds in the literature at Qumran, often in

connection with another important notation in early Christianity, ‘the Way’

terminology.

For Acts, ‘the Way’ is an alternative name for Christianity in its

formative period in Palestine from the 40s to the 50s thrust. Noah is,

therefore, one who is involved in Heavenly ‘ascents’ or ‘journeying’ or at least

one who ‘knows’ the Mysteries of ‘the Highest Angels’. For more on these kinds

of Mysteries see Chapters 5 and 7 below, particularly the Mystery of Existence

text.

This emphasis on ‘Mysteries’ is, of course, strong again in Paul, who in 2 Cor.

12:1- 5 speaks of his own ‘visions’ and of knowing someone ‘caught up into the

Third Heaven’ or ‘Paradise’. One should also not miss the quasi-Gnostic

implications of some of the references to ‘knowing’ and ‘Knowledge’ here and

throughout this corpus. These kinds of allusions again have particular

importance in Chapters 5 and 7.

As the text states, echoing similar Biblical and Kabbalistic projections of

Noah, Noah is someone who

‘knows the secrets of all living things’. Here, the ‘Noahic Covenant’ is not

unimportant, not only to

Rabbinic literature, but also in directives to overseas communities associated

with James’s leadership

of the early Church in Jerusalem from the 40s to the 60s AD. (James also seems

to have absorbed

some of Noah’s primordial vegetarianism.)

This abstention from ‘blood’, ‘food

sacrificed to idols’ (i.e.

idolatry), ‘strangled things’ (probably ‘carrion’ as the Koran 1 6:115

delineates it) and ‘fornication’,

which Acts attributes to James in three different places, are also part and

parcel of the ‘Noahic

Covenant’ incumbent on all ‘the Righteous’ of mankind delineated in Rabbinic

literature. They survive, curiously enough, as the basis of Koranic dietary

regulations, in this sense, the Arabs being one of the ‘Gentile peoples’ par

excellence.

The specifics of Noah’s physical characteristics are also set forth in this

text, and the reference to his being ‘the Elect of God’ is extremely important.

A synonym for Zaddik or ‘Righteous One’ in the minds of the progenitors of this

literary tradition, the term ‘the Elect’ is also used in the Damascus Document

in the definition of ‘the sons of Zadok’ (iv.3f.), showing the esoteric or

qualitative - even eschatological - nature of these basically interchangeable

terminologies. It also appears in an extremely important section of the Habakkuk

Pesher, having to do with ‘the judgement God will make in the midst of many

nations’, i.e. ‘the Last judgement’, in which ‘the Elect of God’ are actually

said to participate (x.13).

The reference to the ‘Three Books’ is also interesting, and certainly these

‘books’ must have been seen as having to do with the mystic knowledge of the

age, or as it were, the Heavenly or Angelic Mysteries. In regard to these, too,

the second half of this text has many affinities with the Chariots of Glory and

Mystery of Existence texts in Chapter 7. AD (Acts 16:16, 18:2 4f., and 2 4:22).

At Qumran it is widespread and also associated with ‘walking’, as well as the

important ‘Way in the wilderness’ proof text. One has phrases like the Perfect

of the Way’, ‘Perfection of the Way’, ‘walking in Perfection’, and the very

interesting ‘Perfect Holiness’ or ‘the Perfection of Holiness’ also known to

Paul in 2 Cor. 7:1.

In this text, too, the Kabbalistic undercurrents should be clear and the

portrayal of Noah as a Wisdom

figure, or one who understands the Secret Mysteries, becomes by the end of

Fragment 2 its main

Translation

Fragment 1

(1) ... (When) he is born, they shall all be darkened together...

(2) he is born in the night and he comes out Perfe[ct...] (3) [with] a weight

of three hundred and fifty] shekels (about 7 pounds, 3 ounces)... (4) he

slept until the division of the days... (5) in the daytime until the

completion of years... (6) a share is set aside for him, not ...years...

Fragment 2

Column 1 (1)... will be ...(2) [H]oly Ones will remem[ber ...] (3)

lig[hts] will be revealed to him (4)... they [will] teach him everything that

(5)... human [Wi]sdom, and every wise ma[n...] (6) in the lands(?),and he

shall be great (7)... mankind shall[be]shaken, and until (8)... he will

reveal Mysteries like the Highest Angels (9)... and with the Understanding of

the Mysteries of (10)... and also (11) ... in the dust (12) ... the Mystery

[as]cends (13) ... portions ...

Fragment 3

Column 2 (7) from... (8) he did... (9) of which you are afraid for all... (1 0) his clothing at the end in

your warehouses. (?) I will strengthen his Goodness ...(11) and he will not die

in the days of Wickedness, and the Wisdom of Your mouth will go forth. He who

opposes You (12) will deserve death. One will write the words of God in a book

that does not wear out, but my words (13) you will adorn. At the time of the

Wicked, me will know you forever, a man of your servants...

Fragment 4

Column

1(1) ... of the hand, two ... it lef[t] a mark from ... (2) barley [and] lentils

on ... (3) and tiny marks on his thigh ...[Aftertw]o years he will be able to

discern one thing from another ... (4) In his youth he will be... all of them

...[like a ma]n who does not know anyth[ing, until] the time when (5) he shall

have come to know the Three Books. (6) [Th]en he will become wise and will be

disc[rete ...] a vision will come to him while upon [his] knees (in prayer). (7)

And with his father and his forefa[th]ers... life and old age; he will

acquire counsel and prudence, (8)[and] he will know the Secrets of mankind. His

Understanding will spread to all peoples, and he will know the Secrets of all

living things.

(9)[A1]1 their plans against him will be fruitless, and the spiritual legacy for

all the living will be enriched. (10) [And all] his [p]lans [will succeed],

because he is the Elect of God. His birth and the Spirit of his breath (11) ...

his[p] fans will endure forever ... (12) that ... (13) pl[an ...

Back to Contents

5. The Words Of

Michael (4Q529)

This text, which could also be referred to as ‘The Vision of Michael’, clearly

belongs to the literature of Heavenly Ascents and visionary recitals just

discussed regarding the birth of Noah and alluded to by no less an authority

than Paul. Such recitals are also common in the literature relating to Enoch and

Revelations.

They are part and parcel of the ecstatic and visionary tendencies

in the Qumran corpus that succeeding visionaries are clearly indebted to,

including those going underground and reemerging in the Kabbalistic Wisdom of

the Middle Ages and beyond. In our discussion of the Mystery of Existence text

in Chapter 7 we highlight some of these correspondences to the work of a writer

like Solomon ibn Gabirol in the eleventh century AD.

This genre can be seen as having one of its earliest exemplars here. The

reference to the Angel Gabriel

in Line 4 is of particular importance and follows that of one of the first such

visionary recitals, Daniel,

a book of the utmost importance for Qumran visionaries and in the Qumran

apocalyptic scheme generally.

Daniel, too, is a work integrally tied to the Maccabean Uprising, as are - at least in spirit - many of the Qumran documents.

As in Dan. 8:16, Gabriel is here the interpreter of the vision or, if one

prefers, the Heavenly or mystic guide though by the end of the vision as extant

in this fragment, it is no longer clear whether Michael or Gabriel is having the

vision. In the Islamic tradition - a later adumbration clearly owing much to the

tradition we see developing here - Gabriel serves as the revealing or dictating

Angel co-extensive with what in Christian tradition might otherwise be called

the Holy Spirit.

Here, whatever else one might say of him, Gabriel is the guide

in the Highest Heaven - traditions about Muhammad too are not immune from such

Heavenly Ascents - not unlike the role, Dante ascribes to Virgil and finally

Beatrice in his rendition of a similar ecstatic ascent and vision.

Here the Archangel Michael ascends to the Highest Heaven. Some practitioners of

this kind of mystic journeying speak of three ‘layers’ (again see Paul in 2 Cor.

12:2), some of seven, and some of twelve. He then appears to descend to tell the

ordinary Angels what he has seen, though, as we have noted, how his role differs

from Gabriel’s is difficult to understand in the text as presently extant. While

in Heaven Michael beholds the ‘Glory of God’ - literally ‘Greatness’ in Aramaic.

Ezekiel - a prophet of the utmost importance in Qumran tradition, not only for

works of this kind, but also for the notion of the ‘sons of Zadok’ terminology

generally - is one of the first to have had such visions relating to the divine

‘Glory’. The terminology is also important in the New Testament and fairly

widespread at Qumran.

Most of the vision is incomprehensible, but one idea, which reappears in Paul

and Kabbalistic tradition generally, is found here that of the New or Heavenly

Jerusalem, i.e. while in Heaven Michael learns of a city to be built. This

apocalyptic and visionary genre clearly owes much to imagery in Daniel and is

reiterated in the pseudo-Daniel works in Chapter 2.

But the actual themes of

Heavenly Ascents and a Heavenly Jerusalem again go all the way back to Ezekiel’s

visions. Not only is Ezekiel picked up by an Angel-like ‘Holy Spirit’ and

deposited in Jerusalem as part of his ecstatic visionary experience early in

that book (Ezek. 8:3), but at the end of the book ascribed to him, he is picked

up again and proceeds to measure out a new Temple (40-48). This theme is the

crux of the next work, which was either directly ascribed to Ezekiel or operated

as part of a pseudo-Ezekiel genre.

Translation

(1) The words of the book that Michael spoke to the Angels of God [after he had

ascended to the Highest Heaven.] (2) He said ‘I found troops of fire there .. .

(3) [Behold,] there were nine mountains, two to the eas[t and two to the north

and two to the west and two] (4)[to the south. There I beheld Gabriel the

Angel... I said to him, (5)’... and you rendered the vision comprehensible.’

Then he said to me . .. (6) It is written in my book that the Great One, the

Eternal Lord... (7) the sons of Ham to the sons of Shem. Now behold, the

Great One, the Eternal Lord ...(8) when ... tears from... (9) Now behold, a

city will be built for the Name of the Great One, [the Eternal Lord]... [And

no] (10) evil shall be committed in the presence of the Great One, [the Eternal]

Lord ...(11) Then the Great One, the Eternal Lord, will remember His creation

[for the purpose of Good]... [Blessing and honor and praise](12)[be to] the

Great One, the Eternal Lord. To Him belongs Mercy and to Him belongs... (13)

In distant territories there will be a man ...(14) he is, and He will say to

him, ‘Behold this... (15) to Me silver and gold ...’

Back to Contents

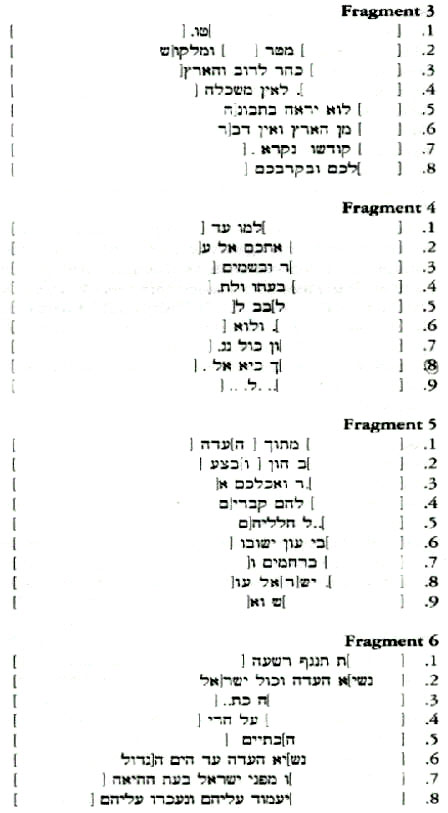

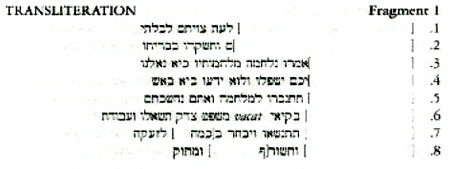

6. The New Jerusalem (4Q554) (Plate 3)

The Aramaic work known as ‘The New Jerusalem’ has turned up in Qumran Caves 1,

2, 4, 5 and 11 with the most extensive portions coming from Caves 4 and 5. The

author is obviously working under the inspiration of Ezekiel’s vision of the new

Temple or the Temple of the end of days referred to above (Ezek. 40-48), which

he elaborates or extends into the ideal picture of Jerusalem. This vision is

reminiscent not only of Ezekiel’s description of how he measures out the new

Temple, but also of parts of the Temple Scroll from Qumran and the New Testament

Book of Revelation.

In the New Jerusalem the visionary, most likely Ezekiel himself though in the

extant fragments no

name is accorded him - is led around the city that will stand on the site of

Zion. His companion,

presumably an Angel - possibly even Gabriel or Michael of the previous visionary

recitals - points out various structures while measuring them with a cane seven

cubits long, i.e. about 10.5 feet.

A precise understanding of the text remains

elusive because of several problems: the use of rare or previously unknown

vocabulary, the many breaks in the manuscripts, and the inherent difficulty of

using words to convey ideas that really require an architectural drawing. In

spite of these problems, these Cave 4 materials contribute substantially to our

knowledge of the city that the author envisaged.

He conceived of a city of

immense size, a rectangle of some 13 x 18 miles. Surrounding the city was a wall

through which passed twelve gates, one for each of the twelve tribes of Israel.

In keeping with the priestly emphasis of the text, an emphasis common to other

texts like the Testament of Levi or the Testament of Kohath, which might

indicate a Maccabean or at least a pro-Maccabean ethos to the vision, the Gate

of Levi stood in the position of greatest honour in the centre of the eastern

wall - that is to say, directly in line with the sacrificial altar and the

entrance to the Temple.

With the Cave 4 additions to what was previously known

of this text, we find that nearly 1,5 00 towers, each more than 100 feet tall

were to guard the city. The final fragment, if it is part of the manuscript in

the manner indicated (Column 11 or later), moves into more apocalyptic and

eschatological motifs. The ‘Kittim’ are specifically referred to. It is

generally conceded that, as in the Book of Daniel, the Kittim refer to the

Romans (Dan. 11:3 0), though in 1 Macc. 1:1 the expression is applied to

Alexander the Great’s forces.

These ‘Kittim’, as noted, are a key conceptuality in the literature found at

Qumran, and reference to them, as we have seen, is widespread in the corpus,

particularly in texts like the War Scroll, the Nahum Pesher, the Habakkuk

Pesher, the Isaiah Pesher a, etc., not to mention the Messianic Leader (Nasi)

text.

The reference here reinforces the impression of the total homogeneity of

the corpus, i.e. that manner of the War Scroll, the Nahum Pesher (where they

come after Greek Seleucid Kings like Antiochus and Demetrius) and the Habakkuk

Pesher, then references to Edom, Moab and the like could refer to various petty

kingdoms what in the Damascus Document are called ‘the Kings of the Peoples’

like the Herodians and others.

At the end of the New Jerusalem the Aramaic equivalent to the word ‘Peoples’ is

also signalled. This is an expression used in the jargon of Roman law to refer

to petty kingdoms in the eastern part of the Empire. In both the Damascus

Document, where the expression ‘Kings of the Peoples’ is actually used (viii.

10) and in the Habakkuk Pesher, where the terms ha—‘Amim and yeter ha-‘Amim

(‘the additional ones of the Peoples’) are expounded Ox. 5T), similar meanings

can be discerned. This expression also has to be seen as generically parallel to

Paul’s important use of it in Rom. 11:11- 13 when describing his own missionary

activities (i.e. he is ‘the Apostle to the Peoples’). However, it is possible

that we do not have a chronological sequentiality here.

At the end of Column 11 according to our reconstruction, it is clear that

Israelis to emerge triumphant;

and there may even be a reference to that Messianic ‘Kingdom’ that ‘will never

pass away’ first

signalled in Dan. 2:4 5 and, in fact, referred to in the Pseudo-Daniel texts

later in this collection. The

intense imagery of these great eschatological events centred in some way on

Jerusalem might seem

strange to the modern reader, but such ideas are directly in line with the

scheme of the ‘tear Scroll

already referred to, not to mention the Book of Revelation, where the same word

‘Babylon’ occurs and is clearly meant to refer to Rome.

That such religious and

nationalistic intensity could be bound up with measurement and the

matter-of-factness of often barren description is precisely the point: the

future could be so certain as to acquire such a patina. This was reassuring

indeed.

Translation

Column 2

(9)...sixteen ...(10) and all of them, from this building ... (11)[and

he measured from] the northeast [corner] (12) [towards the south, up to the

first gate, a distance of] thirty-five [r]es. The name (13) [of this gate is

called the Gate] of Simeon. From [this gat]e [until the middle [g]ate (14) [he

measured thirty-five red. The name of this gate, by which they desig[nate] it,

is the Gate (15) [of Levi. From this gate he measured south]wards thirty-five

res. (16) [The name of this gate they call the Gate of Judah. From] this gate he

measured until the corner (17) [at the southeast; then he measured] from this

corner westwards (18) [twenty-five res. The name of this gate] they call the

Gate of Joseph. (19) [Then he measured from this gate as far as the middle

gate,] twenty-five [re]s. (2 0) [This gate they call the Gate of Benjamin. From]

this ga[te] he measured as far as the [third] gate, (2 1) [twenty-five res. They

call this one] the Gate of Reuben. And [from] this [ga]te (22)[he measured as

far as the western corner, twenty-five res.] From this corner he measured as far

as ...

Column 3

(5)... he meas]ured (6)[twenty]five [res. They call this gate

the Gate of Dan. And he measured] from [this] gate [to] (7) the middle [gate],

[25] res. And they call that gate the Gate of Naphtali. From (8) the gate he

measured to the [g]ate... and they call the name of that gate (9) the Gate of

Asher. And he m.eas[ured from] that ga[te] to the northern corner, (10) 2 5 res.

(11) And he brought me into the city, and measured every block for length and

width: 51 (12) canes by 51 canes square, 357 (13) cubits in every direction. And

a free space [s]urrounded the squares on the outside of (each) street: (its

measurement) in canes (14) three, in cubits 21. In Mike manner he [sh]owed me

the measurements of all the squares. Between every two squares (15) ran a road,

width (measuring) in canes six, [in cubits 42]. As for the great roads which

went out (16) from east to wes[t, (they measured) in canes] as to width ten, in

cubits (17) 7 0 for 2 of them; a t[hi]rd, which was on the n[orth] of the

temple, he measured (18) at 18 canes width, [which is in cubits one-hundred and

twenty s]ix. As for the width (19) of the streets which went out from s[outh to

north, two of them were] nine caked (20) 4 cubits each, [which is sixty seven cu]bits. And he measured [the central one, which was in the mid]dle of the (21)

city. Its width: [13 ca]nes [and one cubit, in cubits 9]2.(22) And every street

and the entire city was [paved with white stone].

Column 4

(1)... marble and jasper. And he showed me (2) the dimensions of the

eighty side doors. The

width of the side doors was two canes, i.e., fourteen cubits. (3) ... each gate

had two doors made of

stone. The width of the doors (4) was one cane, i.e., seven cubits. Then he

showed me the dimensions

of the twelve . .. The width (5) of their gates was three canes, i.e.,

twenty-one cubits. Each such gate

possessed two doors. (6) The width of the doors was one and one-half canes,

i.e., ten and one-half

cubits ... (7) Alongside each gate were two towers, one to the right (8) and one

to the left. Their width

and their length were identical: five canes by five canes, by cubits (9) thirty

five. The staircase that

ascended alongside the inner gate, to the right of the towers, was of the same

height as (10) the

towers. Its width was five cubits. The towers and the stairs were five canes and

five cubits, (11) i.e.,

forty cubits in each direction from the gate. (12) Then he showed me the

dimensions of the gates of

the blocks of houses. Their width was two canes, i.e., fourteen cubits.] (13)

And the width of the . ..,

their measurements in cubits. Then he [measured] the width of each threshold,

(14) two canes, i.e.,

fourteen cubits; and the roof, one cubit. [And above each thres]hold [he

measured] (15) the doors that

belonged to it. He measured the interior structure of the threshold, length

four[teen cub]its and width

twe[nty-one cubits.] (16) He brought me inside the threshold, and there was

another threshold and yet another gate. The interior wall off to the right had

(17) the same dimensi[ons] as the exterior gate: its width, four cubits; its

height, seven cubits. It had two doors. In fron[t of] (1 8) this ga[te] was a

threshold extending inwards. Its width was [o]ne cane-seven cubits-and its

length extended toward the inside two canes or (19) fourteen [cu]bits. Its

height was two canes, i.e., fou[r]teen cubits. Gates opposed gates, opening

toward the interior of the bloc[ks] of houses, (20) each possessing the

dimensions of the outer gate. On the left of this entry way he showed me a

building housing a sp[iral] staircase. Its wid[th] was (21) the same in every

direction: two canes, i.e., fourteen cubits. G[ate opposed gate], (22) each with

dimensions corresponding to those of the house. A pillar was located in the

middle of the structure [upon which] the staircase was supported as it spir[aled

upward. Its (the pillar’s) width and length

Column 5

(1) were a single

measurement, six cubits by six cubits square.] The staircase tha[t rose by its

side] was four cubits wide, spiraling [upward to a height of two canes until...] (3) [Then he brought me inside the blocks of houses and showed me houses

there,] fifteen [from gat]e to gate: eight in one direction as far as the

corner, (4)[and seven from the corner to the other gate.] The length of the

houses was three canes, i.e., twenty-one cubits, and their width (5) [was two

canes, i.e., fourteen cubits. Of corresponding size were all the chambers.]

Their height was two canes, i.e., fourteen cubits, and each had a gate in its

middle. (6)[...flour. Length and height were a single cane, i.e., seven cubits.

(7) ... theirleng [th], and their width was twelve cubits. A house (8)...

alongside it an outer gutter (9) [...The heig]ht of the first was...

cubits. (10) The..., and their width was .. . cubits. (11)... two canes,

i.e., four[teen] cubits (12) [...cu]bits one and one-half, and its interior

(?) height (13)... the roof that was over them Column 9 (or later) (14)... two [can]es, (15) [i.e., fourteen cubits...] cubits (1 6)... the

measurement of (17)[... the bound]cries (?) of the city Column 10 (or later)

(13)... its foundation. Its width was two canes, (14) i.e., fourte[e]n

cubits, and its height was seven canes, i.e., forty-nine cubits. And it was

entirely (15) built of elect[rum] and sapphire and chalcedony, with laths of

gold. Its (the city’s) towers numbered one thousand (16)[four hundr]ed

thirty-two. Their width and their length were a single dimension, (17)... and

their height was ten canes, (18) [i.e., seventy cubits... two canes, i.e.]

fourteen [cubits.] (19) [...th]eir length (20)... the middle one ... cubits

(21)... two to the gate (22)[in every dir]ection three towers extended Column 11

(or later) (15) after him and the Kingdom of... (16) the Kittim after him,

all of them one after another... (17) others great and poor with them ...(18)

with them Edom and Moab and the Ammonites... (19) of Babylon. In all the earth

no ...(20) and they shall oppress your descendants until such time that ...(21)

among all natio[ns,the] Kingdom ...(22)andthe nations shall ser[ve] them ...

Back to Contents

7. The Tree Of Evil (A Fragmentary Apocalypse-4Q458)

We close this Chapter with another work in the style of the Words of Michael and

these final

sentences of the New Jerusalem. This Hebrew apocalypse, while fragmentary, again

recapitulates

themes known across the broad expanse of Qumran literature, most notably tem{c}a

(polluted),

teval{c}a (swallow or swallowing), ‘walking according to the Laws’, yizdaku

(justified or made

Righteous), etc. These themes should not be underestimated and reappear

repeatedly in the Damascus Document, the Temple Scroll, Hymns, and the like.

‘Swallowing’ has particular importance vis-à-vis the fate of the Righteous

Teacher and his relations with the Jerusalem establishment, i.e. ‘they consumed

him.’ ‘Justification’ also has importance via-à-vis his activities and those of

all the ‘sons of Zadok’ (primordial Zaddikim Righteous Ones), who in CD, iv

above ‘justify the Righteous and condemn the Wicked’ - this in an eschatological

manner.

It also has to do, as Paul demonstrates, with the doctrine of

Righteousness generally. ‘Pollution’ - particularly Temple Pollution - is one of

‘the three nets of Belial’, referred to as well in Column iv of the Damascus

Document, and we shall discuss it below. It usually involves charges against

this upper-class establishment, relating to the foreign appointment of high

priests, consorting with foreigners and foreign gifts or sacrifices in the

Temple.

As fragmentary as the Tree of Evil text is, there are apocalyptic references to

‘Angels’, ‘burning’, ‘flames’, etc. Images like ‘burning fire’ have an almost

Koranic ring to them, as do references to ‘the moon and stars’. There is also an

intriguing reference to ‘the beloved one’ - possibly referring to Abraham as

‘friend of God’ - of the kind one finds in texts like the Damascus Document and

notably the Letter of James.

We shall meet these references to Abraham as

‘beloved’ again below. Some might wish to consider its resonance’s with ‘the

beloved apostle’ in the Fourth Gospel. The text also evokes ‘the Tree of Evil’,

most likely an eschatological reference to the Adam and Eve story. The language

of ‘polluting’ and ‘pollution’ runs all through Qumran literature, particularly

the Damascus Document, the Habakkuk Pesher, the Temple Scroll and the two

Letters on Works Righteousness in Chapter 6 below. It use in this text,

particularly in relation to the parallel allusions to ‘swallowing’ and

‘foreskins’, is important.

One finds the same combination of themes in the Habakkuk Pesher, xi.13 - 15.

There the usage deliberately transmutes an underlying scriptural reference to

‘trembling’ into an allusion about the Wicked Priest ‘not circumcizing the

foreskin of his heart’. This image plays on Ezek. 44:7 -9’s reconstructed Temple

vision, also including the language of pollution of the Temple. This last image

is specifically related to the demand to ban from it rebels, Law-breakers,

foreigners and those ‘of uncircumcized heart’.

This is also the passage used to

define ‘the sons of Zadok’ in the Damascus Document above. Here in the Habakkuk

Pesher, what is being evoked is the imagery of apocalyptic vengeance relating to

the ‘swallowing’ of the Wicked Priest and his ‘swallowing’, i.e. destruction, of

the Righteous Teacher (xi.5 -7 and xii.5 -7). These passages also play upon the

image of the ‘cup’ of the Lord’s divine ‘anger’. This genre of apocalyptic

imagery is also found in Isa. 6 3:6 and Rev. 14:10. This ‘swallowing’ imagery at

Qumran is linguistically related too to a cluster of names like Bela{c}(an

Edomite and Benjaminite king name), Balaam and Belial - this last a name for the

Devil at Qumran.

For New Testament parallels to all of these names, see Paul on

Christ and ‘Beliar’ in 2 Cor. 6:15, 2 Pet. 2:15, Jude 1:11 (interestingly enough

preceded by an allusion to the Archangel Michael disputing with the Devil) and

Rev. 2:14. This cluster parallels the more Righteousness oriented one we have

been delineating above.

In this text, too, the allusion that follows is to the fact that ‘they were

justified’ or ‘made Righteous’,

again heavy with portentousness for early Christian history. The ‘justification’

referred to has, of course, to do with ‘walking according to the Laws’, a

typically ‘Jamesian’ (as opposed to ‘Pauline’) notion of justification. It is

encountered across the spectrum of Qumran documents - for instance, at the end

of the Second Letter on Works Righteousness in Chapter 6 below and in the

definition of ‘the sons of Zadok’ above.

Again, the nationalist, Law-oriented nature of the apocalypse should be clear,

but the last line is portentous too. We have read the word mashuah in it as

‘anointed’, but it could just as easily be read ‘Mashiah’ - Messiah (i and ulo

being interchangeable in Qumran epigraphy) - which then adds to the weightiness

of the text. However this may be, that this text is now moving into some concept

of ‘Kingdom’ or ‘Kingship’, possibly that ‘Kingdom’ in Dan. 2:44 mentioned above

‘that will never be destroyed’, is self-evident.

Translation

Fragment 1

(1) ... to the beloved one ... (2) the beloved one ... (3) in the

tent... (4) they did not know... (5) burning of fire... (6) and the

peoples of the ... arose ... (7) spoke to the first, saying ...(8) flames, and

He will send the first Angel... (9) drying up. And he smote the Tree of

Evil... Fragment 2 Column 1 (2) [... the mo]on and the stars (3)... the years

(4)... he fled in (5) ... the polluted (one) (6) ... the harlots(?)

Fragment 2 Column 2 (2) And he destroyed him, and ...(3) and swallowed up all

the uncircumcised, and it ...(4) And they were justified, and walked according

to the L[aws... (5) anointed with the oil of the Kingship of ...

Back to Contents

Notes

(1) The Messiah of Heaven and Earth (4Q5 2 1)

Previous Discussion: R. H. Eisenman, ‘A Messianic Vision’, Biblical Archaeology

Review Nov/Dec (1991) p. 65.

Photographs: PAM 43.604, ER 1551.

(2) The Messianic Leader (Nasi-4Q285)

Previous Discussions: None. A discussion, taking as its starting point our

announcement of this text in November 1991: G. Vermes, ‘The Oxford Forum for

Qumran Research Seminar on the Rule of War from Cave 4 (4Q285)’ will be

forthcoming in the Journal of Jewish Studies.

Photographs: PAM 43.285 and

43.325, ER 1321 and 1352.

(3) The Servants of Darkness (4Q57 I)

Previous Discussions: None.

Photographs: PAM 42.914 and 43.551, ER 1054 (43.551

not listed). The DSSIP lists the text as 4QM(g).

(4) The Birth of Noah (4Q534 - 5 36)

Previous Discussions: J. Starcky, ‘Un texte messianique araméen de la grotte 4

de Qumrân’, École des

langues orientales anciennes de l’Institut Catholique de Paris: Mémorial du

cinquantenaire 1914 -1964

(Paris: Bloud et Gay, 1964) 51-66; Milik, Books of Enoch, 56.

Photographs: PAM 4

3.572 (bottom),

43.575, 43.590 and 43.591, ER 1520, 1523, 1537 and 1538. Our Fragment 1 is an

eclectic text based

on Birth of Noah Manuscripts C and D. Fragment 2 represents portions of

Manuscript D. Fragment 3

has been known as 4QMessAram; it is not certain - merely probable that it is a

third copy of the Birth

of Noah text.

(5) The Words of Michael (4Q529)

Previous Discussion: Milik, Books of Enoch, 91.

Photograph: PAM 43.572 (top), ER

1520.

(6) The New Jerusalem (4Q549)

Previous Discussions: Milik, DJD 3, 184-9 3; J. Starcky, ‘Jerusalem et les

manuscrits de la met Morte’, Le Monde de la Bible 1 (1 97 7) 3 8-40; Beyer,

Texte, 214-22.

Photographs: PAM 41.940, 43.564 and 43.589, ER 521, 15 12 and 15

3 6. The restorations of column 4 are possible because it overlaps with

preserved portions of the New Jerusalem text from Cave 5.

(7) The Tree of Evil

(A Fragmentary Apocalypse - 4Q4 5 8)

Previous Discussions: None.

Photograph: PAM 43.544, ER 1493.

Back to Contents