|

by Wallace Thornhill

Jul 18, 2005

from

Thunderbolts Website

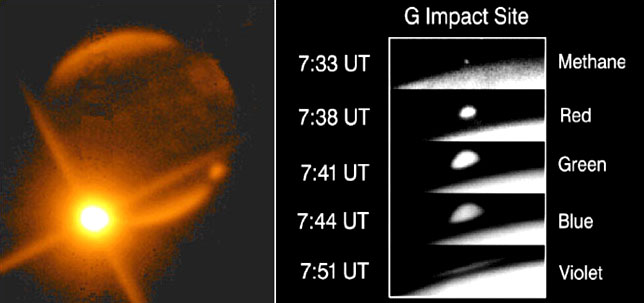

LEFT: Hubble Space

Telescope view of the plume from Shoemaker-Levy 9

Fragment G impact, appearing around the limb of Jupiter.

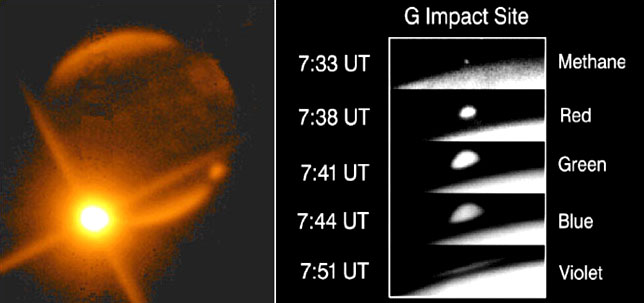

RIGHT: Fragment G impact. Image at 2.34 microns with CASPIR by Peter

McGregor ANU 2.3 telescope at Siding Spring

To place the Deep Impact events in

perspective, advocates of the electric comet model remind us of the

crash of the comet

Shoemaker-Levy 9 into Jupiter in 1994.

For some time now the electrical theorists have noted that the

institutionalization of scientific inquiry, in combination with

funding requirements, has encouraged a short attention span. The

things that do not fit prior theory elicit a momentary expression of

surprise, but as the events pass from view they are quickly

forgotten.

“What we cannot comprehend, we shall forget”.

So it is that already the stupendous explosion produced by Deep

Impact—the blast of light that shocked every member of the

investigative team—is fading from the consciousness of the

investigators. And just two weeks after Deep Impact, all discussion

of the equally remarkable advanced flash has ceased. Perhaps none of

the NASA scientists knew that the electrical theorists had predicted

these events in advance.

Here is an interesting fact. When looking forward to the Deep Impact

mission in October 2001, Wallace Thornhill observed:

“…the energetic

effects of the encounter should exceed that of a simple physical

impact, in the same way that was seen with comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

fragments at Jupiter.”

We gave the reasoning in our predictions

posted early in the day, July 3: The energy of the explosion will

not come just from a collision of solid bodies, but will include the

electrical contribution of the comet.

Thornhill had not forgotten an earlier surprise, though it appears

that no one involved in Deep Impact remembered what happened when

comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 approached Jupiter in the summer of 1994.

Astronomers expected the encounter to be a trivial event.

“You won’t

see anything. The comet crash will probably amount to nothing more

than a bunch of pebbles falling into an ocean 500 million miles from

Earth.”

Then came the encounter and an about face. As reported by

Sky & Telescope,

“When Fragment ‘A’ hit the giant planet, it threw

up a fireball so unexpectedly bright that it seemed to knock the

world’s astronomical community off its feet.”

So a brief summary of

some of those earlier events are provided below. For a more detailed

article see Comet Tempel 1's Electrifying Impact.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) detected a flare-up of fragment “G”

of Shoemaker-Levy long before impact at a distance of 2.3 million

miles from Jupiter. For the electrical theorists this flash would

occur as the fragment crossed Jupiter’s plasma sheath, or

magnetosphere boundary.

Thornhill comments:

“A plasma sheath, or

‘double layer’, is a region of strong electric field, so the

outburst there of an electrified comet nucleus is expected. The

outburst was a surprise to astronomers. Hubble’s Faint Object

Spectrograph (FOS) recorded strong emissions from fragment ‘G’ of

ionized magnesium but no hydroxyl radical (OH), expected from water

ice”.

Also, after the flare-up in magnesium emissions there was a

“dramatic change in the light reflected from the dust particles in

the comet”. All told, the similarities to the Deep Impact flash are

remarkable.

Just after the impact of SL-9 fragment “K”, HST detected unusual

auroral activity that was brighter than Jupiter’s normal aurora and

outside their normal area. Radiation belts were disrupted. There

were unexpectedly bright X-ray emissions at the time of impact. But

one mystery was never explained satisfactorily: Early impact events

were hidden from the Earth behind Jupiter’s limb. However, the

Galileo spacecraft was positioned 150 million miles away from

Jupiter at an angle that gave it a ringside seat for these events.

But Earth-based observatories saw some of the impacts start at the

same time Galileo did.

“In effect, we are seeing something we didn’t

think we had any right to see,” said Dr. Andrew Ingersoll of

Caltech. “...it seems clear that something was happening high enough

to be seen beyond the curve of the planet,” said Galileo Project

scientist Dr. Torrence Johnson of JPL.

None of these discoveries is surprising if comets are highly

electrically charged with respect to their environment. Radio

astronomers had expected radio emissions from Jupiter at high

frequencies to drop because dust from SL-9 fragments would absorb

electrons from the radiation belts, where the electrons emit

synchrotron radiation.

Instead, observers were surprised to find

that emissions around 2.3 GHz rose by 20-30%.

“Never in 23 years of

Jupiter observations have we seen such a rapid and intense increase

in radio emission,” said Michael Klein of JPL. “Extra electrons were

supplied by a source which is a mystery.”

It never occurred to

anyone that the charged comet was the source of the electrons.

Will the rapid exclusion of uncomfortable facts continue as we await

data analysis of Deep Impact?

|