|

by Wallace Thornhill

Jul 08, 2005

from

Thunderbolts Website

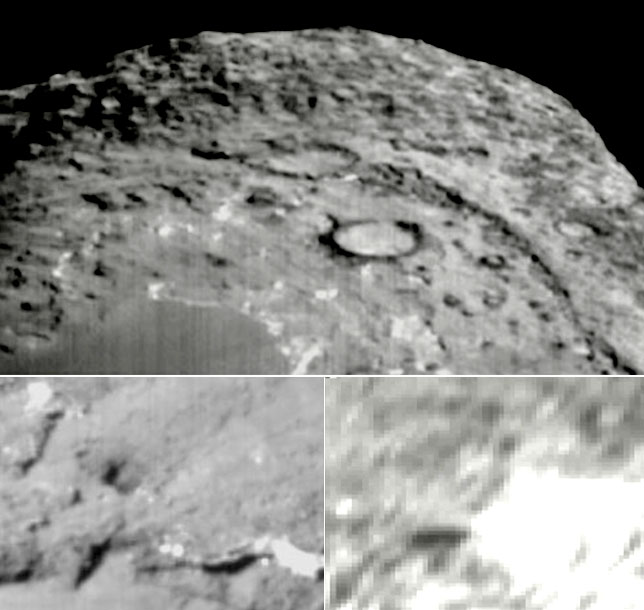

Credit:

NASA/JPL--Caltech/UMD

We’ll hold off on a celebration for now,

but the pictures above appear to exhibit some of the “smoking guns”

that the electric theorists have predicted.

The single most dramatic prediction of the electric comet model is

this: on close inspection an active comet nucleus will reveal the

electrical arcs that progressively etch away the surface and

accelerate material into space. From the electrical vantage point,

Tempel 1 is a “low voltage comet”, but the etching process appears

to be sufficiently active to make our case.

The white spots were noticed by the Thunderbolts crew as soon as the

first pictures were released, and we offered an interpretation: they

are small electric arcs analogous to the discharge plumes on

Jupiter’s moon Io, and to the electrified dust devils on Mars.

On

July 6 we drew attention to an earlier Picture of the Day observing

bright spots on Wild 2. There we suggested that these were the

patches of electric discharge at the surface. Now, with the help of

the Deep Impact images, that interpretation is further illuminated

and strengthened.

In addressing these fuzzy white areas in one of the pictures taken

by the projectile prior to impact, NASA reports,

“The bright patches

in the image may consist of very smooth and reflective material, the

composition of which will be determined by Deep Impact's

spectrometer”.

NASA’s observations came two days after impact, and the language

used invites us to make further predictions. The patches will have

nothing to do with “reflectivity”. They are better explained as the

light of focused glow discharges, showing up as fuzzy whiteouts.

They are the cometary equivalent to “St. Elmo’s fire” – coronal glow

discharges sometimes observed dancing on high points in lightning

storms on Earth.

Similar, but more powerful arcs on Jupiter’s moon

Io produced whiteouts that overloaded the Galileo probe camera and

surprised the investigators. These discharges on the comet’s surface

should show emission lines from ionized surface material and be

emitting ultraviolet light (something that arc welders know

well—it’s why they wear welder’s masks and protective clothing).

And if the instruments on either the projectile or the spacecraft

obtained measurements at sufficient resolution to detect

unexpectedly high temperatures at the point source, NASA

investigators will be in for quite a surprise. Electric arcs are

hot!

Does NASA have the required data buried in the transmissions from

Deep Impact?

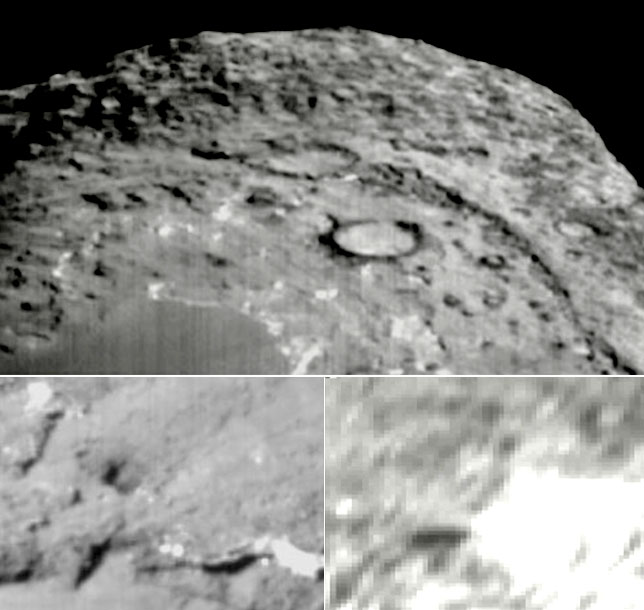

One reason for cautious optimism is the size of the

whiteouts in the last pictures taken before the projectile’s

camera’s shut down some 18 miles above the surface. (The very last

picture is seen in the lower right). Both ultraviolet light

emissions and “shocking” temperatures within the white spots would

be definitive evidence for the electrical nature of comets.

When researchers investigating the Electric Universe express

enthusiasm for comet study, a point of particular interest is the

possibility that, by observing electrical arcing in action, we could

see more clearly the relationship to the geology-in-formation on the

comet nucleus.

Several years ago, Wallace Thornhill accurately predicted what

Galileo investigators would find when they looked at the “volcanoes”

on Jupiter’s closest moon Io. He said that the plumes would not be

“volcanoes” but discharges moving around the edges of the excavated

areas, exactly as NASA discovered on Io, and as now appears to be

occurring on Tempel 1. He said the plumes would be much hotter than

NASA officials expected (in fact they produced the same kind of

whiteouts now seen on Tempel 1).

And he said that the supposed “lava

lakes” on Io would be cold (they are simply the excavated terrain

beneath the surface, exposed by the etching process.) Now it is

becoming more clear every day that Thornhill’s successful

predictions for Io, make what is happening on Tempel 1 all the more

significant. In the above pictures we see that the dominant

positions of the white spots are on the rims of craters and the

cliffs rising above valley floors. A particularly telling example of

this relationship is seen in the picture here

In fact the active areas in the upper picture above reveal uncanny

similarities to the discharge activity on Io as observed in previous

Pictures of the Day. One of the features of electric arc erosion

noted by Thornhill many years ago, is the tendency to create

scalloped edges as it cuts away material from the cliffs edges it is

acting on.

This tendency we see abundantly on Io, which makes an

observation in a NASA release on Deep Impact all the more

noteworthy:

"The image [of the nucleus] reveals topographic

features, including ridges, scalloped edges and possibly impact

craters formed long ago”.

(The phrase “long ago” has no scientific

basis; it is merely the projection of an unfounded assumption;

continual ablation of cometary ices by solar heating of the surface

would not permit the preservation of such abundant, sharply defined

craters for long periods of time).

On Io, the darkest surfaces are associated with recent arcing along

the edges of craters and cliffs, exposing the underlying rock.

Electrostatic fallback of ejecta covers the flat areas with lighter

material. The same thing seems to hold true for Tempel 1. The crater

rims and ridges are darkest. The circularity of the craters is also

characteristic of arc machining and is not to be expected from

low-velocity impacts in the outer solar system.

One claim that sharply distinguishes the Electric Universe

hypothesis from standard models is its emphasis on the electrical

sculpting of rocky surfaces in the solar system throughout its

eventful history. From planets and moons to comets and asteroids,

the electrical model suggests that numerous surface features are the

effect of electrical etching. For this reason, comets have the

potential to bring new clarity to our understanding of planetary

geology.

Finally, why were there no images returned from the impactor seconds

before impact? The lower right image is the last from the impactor

camera. Thornhill predicted an electrical flash before impact.

Yesterday’s TPOD reported the surprise expressed by NASA’s expert on

high-velocity impacts, Peter Schultz, when two flashes were seen.

The lack of images in the last few seconds would be explained simply

if the impactor was hit by a “cometary lightning bolt” seconds

before contact. The “whiteout” seen in the lower right quadrant

indicates significant electrical discharging near the impact point.

Data from the communications team and the flyby spacecraft cameras

should decide the issue.

|